Peter Gatien is still the Club King of New York

Party promoter Neville Wells (left) and Peter Gatien at the Limelight, 1993. New York. Courtesy of Getty Images.

The nightlife impresario of Manhattan owned four superclubs in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and a new memoir takes stock of his legacy – from the story of Party Monster's disgraced club kid Michael Alig to a merciless takedown by Rudy Giuliani.

Culture

Words: Trey Taylor

“I was the face of nightlife. I had four of the biggest clubs in town. The most written about, whether nationally or internationally. I had the best staff, the best DJs, the best this, the best that…” Peter Gatien, 67, says over the phone from his Toronto home.

The man crowned the Club King of New York is being humble. He wanted to meet me at Bowery Bar, pre-pandemic, to chew over the line items of his formidable career as the preeminent swizzle stick in the cocktail of Manhattan nightlife. Gatien was a mixologist of the nocturnal rank and file with the MO of “creating culture”, as he often reminded his staff.

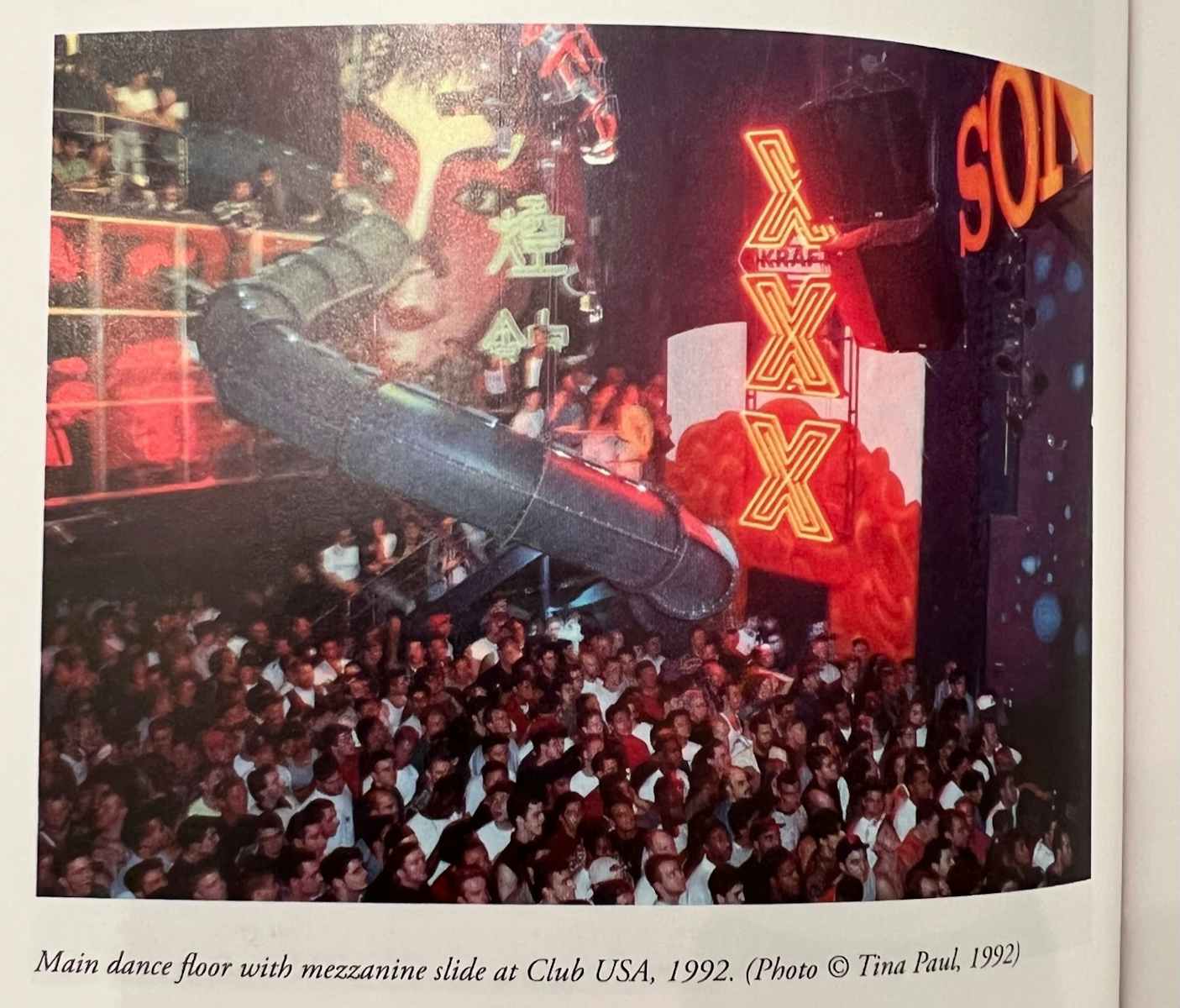

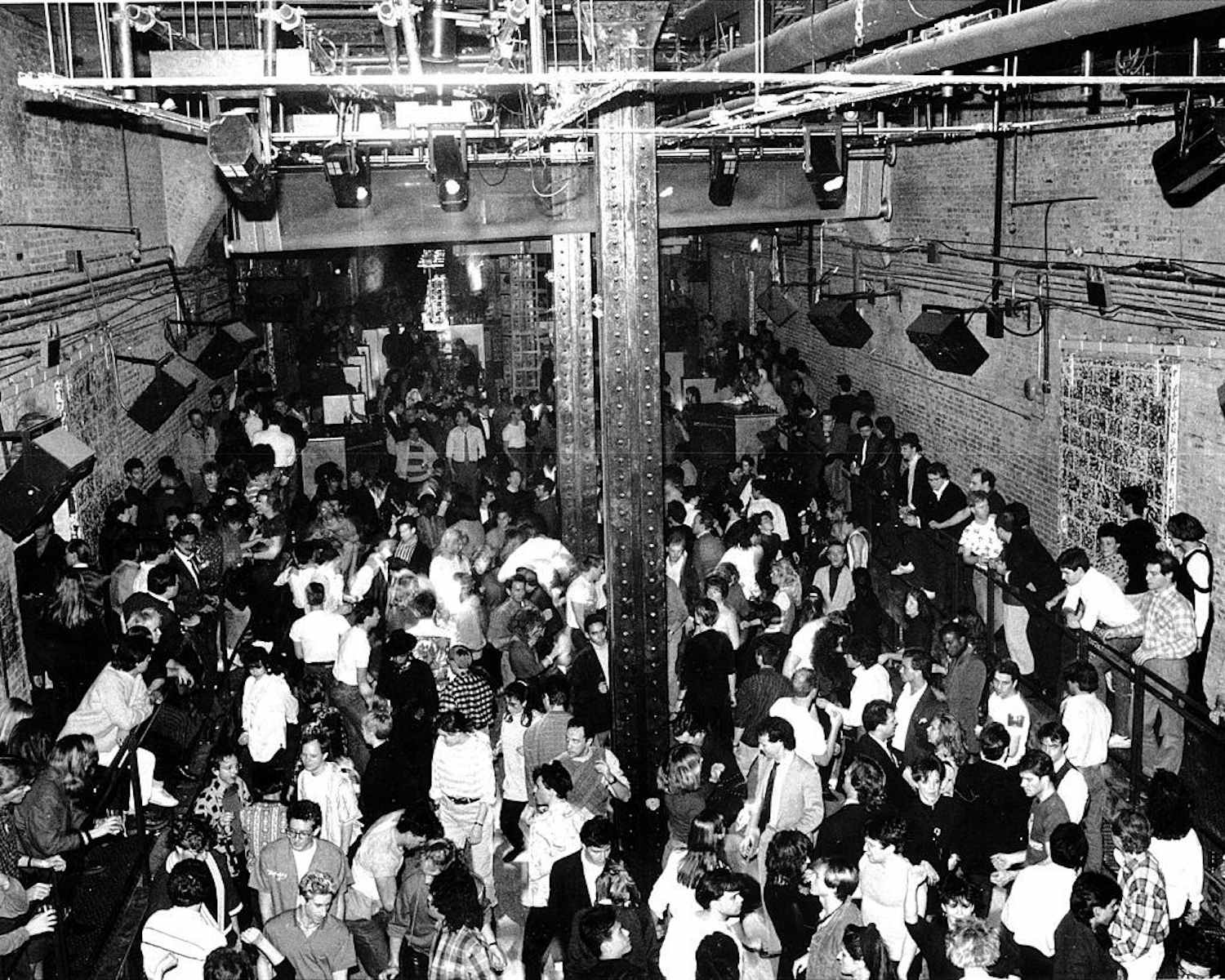

Studio 54 lasted only 18 months. Gatien’s New York clubs – Palladium, Club USA, Tunnel, and most importantly, Limelight – spanned 17 years in the ‘80s and ‘90s. It was not the buildings, he avows (though they were colossal and unique), nor the spectacle (though he lured clubbers with live panthers, gilded cages and top-tier performances), but the eccentric queerdos at Limelight’s Disco 2000, the celebrities at Communion or the rough-n-ready rappers at Tunnel Sundays that made him famous and very, very rich.

Then his empire imploded. Nightlife-murdering NYC mayor Rudy Giuliani hauled him over the bureaucratic coals of state-funded court trials until his funds were dried up. Gatien was charged with conspiracy to distribute party drugs in his clubs. The FBI were aided by disgraced club kid Michael Alig and other drug-addicted informants. All the claims were baseless, but they eventually got Gatien on tax evasion (he had paid his employees in cash). In 1999, he was deported back to his home country of Canada, where he now lives with his wife and children.

He’s full of stories, and, after years of being hounded, has sandwiched them all between two graphic neon covers for his first memoir titled The Club King: My Rise, Reign & Fall in New York Nightlife.

Click on the red arrows to reveal excerpts from Gatien’s book.

Michael Alig, Richie Rich, Nina Hagen, Sophia Lamar, and Genetalia at Tunnel Club, New York, December 31, 1993. Courtesy of Getty Images.

Donatella Versace and Jennifer Lopez attending “Notorious” magazine party at the Limelight, 1999. Courtesy of Getty Images.

Tunnel Disco night club at 29th and 12th Avenue in Manhattan, one of the hottest of hot spots, 1987. Courtesy of Getty Images.

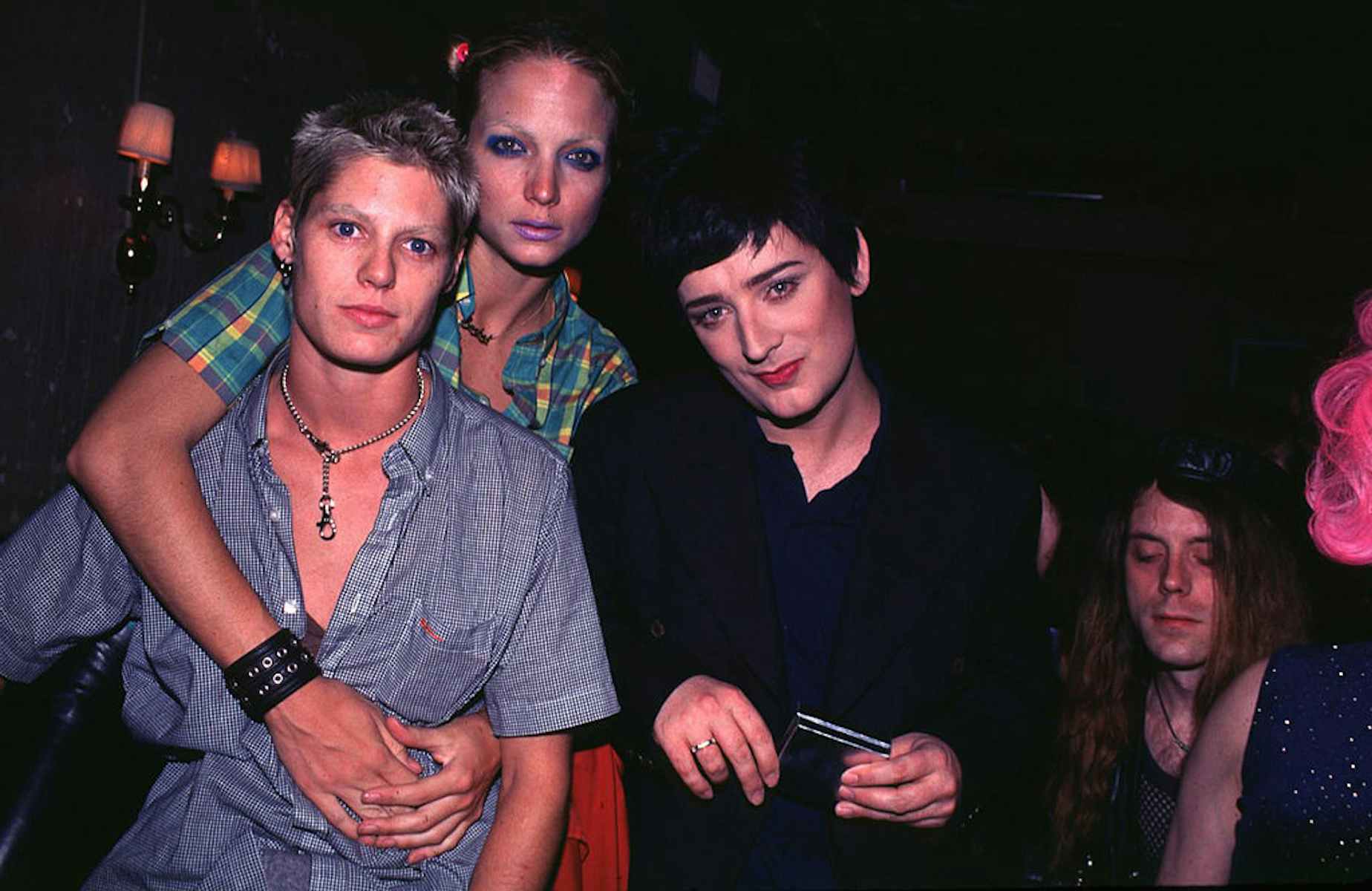

Rachel Williams, Alice Temple & Boy George at Tunnel, 1995. Courtesy of Getty Images.

In a 2011 New York Times interview, you said you were trying to write a memoir. Has it really been nearly a decade in the making?

For years a lot of people have told me, “You really need to write your stories, there’s a lot of misconception out there.” So I did it. My daughter was an independent film producer, pitching a movie to Amazon. They said, “[That idea is] not for us, what else are you working on?” She said, “I’m working on my father’s story.” She just happened to have [a copy of the] book with her. She left and then ten minutes later they called back and said “Don’t go anywhere, we want to do this movie.” Since then, Nick Pileggi has written the screenplay; he wrote Casino, he wrote Goodfellas – he’s a legendary screenwriter. It’s basically my life from mostly 1990 to my deportation. We’re in the final polish now. Were you in New York in the ‘90s?

No, I wasn’t. I wish.

Well, you missed something. A lot of legendary nights came out of clubs over the years, Limelight later [during its run], but the hip-hop night on Sundays – everyone from Jay‑Z to Mary J. Blige to Puffy to Nas, Biggie Smalls to Tupac, they all performed there. The night ran literally for nine years, and for the black community, Sunday night was that important. Vibe wrote an article in 1996 crediting Sunday night Tunnel as being the incubator of mainstreaming hip-hop. I mean the way we talked, the way we dressed, the music we listen to now is basically because of hip-hop.

“Biggie used to come all the time with a gun on him, a little over-and-under derringer,” remembered Lee Coles. “We must have taken that fucking thing away from him a dozen times.”

Sean "Puffy" Combs at The Limelight for the launching of his new magazine, Notorious Magazine, 1999. Courtesy of Getty Images.

I think it was one of Biggie‘s first performances, at Tunnel Sundays.

We had 2000, 3000 people every Sunday, week in and week out.

What was your relationship with Biggie?

I was never a Steve Rubell. Nobody came to the Tunnel because Peter Gatien was there, they came because of the great nights that we put together. So what was my relationship with Biggie? You know, I was courteous to everybody, I would shake hands, and that was it.

Did Tupac really shoot up the marquee of Palladium?

Yeah, that’s a true story. I met him a couple times. Actually, he always seemed pretty nice, to be honest with you. But he could do things to draw attention for sure.

What do you remember of that night?

I remember going to Palladium, and he had just left. And there were holes in the marquee. Obviously, I wasn’t there when he pulled the gun out, but apparently it was not done maliciously – almost like a clown type thing. How do you react to something like that? It was not a normal thing to happen at the club.

For reasons known only to him, Tupac Shakur once appeared outside Palladium and began to shoot up the club’s marquee. We had to get the mercurial rap star bundled off and away from the scene before the cops showed. That incident happened around the same time that Johnny Depp came into Club USA to research his role for Donnie Brasco, bringing along a crew of street guys who were helping him get in character. True to form, his mob people and my security personnel got into a brawl over entry into the VIP room.

“I’ve been described as a shadowy figure in the background, but the lesson I learnt as a young kid with my first club is, you’re in the service industry, it’s really important to inspire your staff. If your staff sees you half in the bag or not on top of things, it sends a message that it’s cool to sneak a couple drinks if you’re working behind the bar.”

The press during your reign as the Club King of New York always painted you as this aloof, cagey person holed up in his office counting money, and I was wondering if you resented that.

I didn’t count the money, the staff counted money. I’ve been described as a shadowy figure in the background, but the lesson I learnt as a young kid with my first club is, you’re in the service industry, it’s really important to inspire your staff. If your staff sees you half in the bag or not on top of things, it sends a message that it’s cool to sneak a couple drinks if you’re working behind the bar. I was never the life of the party, nor did I want to be, and quite frankly, physically, you can’t do it. Forget about drugs, you can’t even drink every night. Your body’s unable to handle that kind of strain on it. Not if you’re working like I was, literally 16 hours on any given day, seven days a week.

I want to hear more about how you came to meet Tony Pellegrino.

The most interesting soul I encountered in the entire quarter century that I owned clubs was Tony Pellegrino. I’d met Tony when he casually dropped by the club one afternoon, saying he had been in Limelight the night before and liked the vibe. After he mentioned that he had mustered out of the US Marine Corps with the rank of major, I immediately hired him as an assistant security manager.

“Honorably discharged as a major – that’s pretty good, isn’t it?” he asked rhetorically. “Especially for someone whose uncle was Carlo Gambino?”

He just showed up one day. It wasn’t that he looked weird, but he was like 12 years older than all of [the staff]. He seemed like a nice guy, and he started talking with security guys and then the head of security said, “This guy Tony, he’d like to work here, he’s a marine.” Like, “Yeah, sure fine,” and then he became my personal driver.

Is he still alive?

I don’t know. I think this guy was just a black ops, CIA-type. His background was in the marines. I don’t know what he was, but he was a person that I’ll never forget. And as a young kid, I was probably 27 or whatever, it just gave you a sense of power. He had ID in his name for everything. He used to pick me up on the tarmac at the airport. He’d put a police bubble on the roof of the limo and – I laugh when I think of it now – we‘d just zip through town. If there was a parade or something that we had to get through, he‘d show the cops some ID, and we were ushered right through. It was crazy.

I know Andy Warhol was a big part of promoting your venues when they opened. Did you ever develop a personal relationship with him?

I probably went out to dinner with him four to eight times. Were we best of buddies where he’d call me up and say “Hey, Peter”? No. He was a really nice man. The ‘70s were all about chrome, neon, spinning wheels, and the ‘80s. I saw architecture and art becoming important. Warhol and Basquiat and that whole art movement in New York – they were trendsetters back then. So yeah, Warhol gave us a lot of credibility.

I read that, for a time, you were making half a million a week between all four of your clubs.

The four clubs represented over a quarter million square feet of prime Manhattan real estate – 251,000 square feet, to be exact. Their official capacities totaled 18,000 party-till-you-drop club-goers, though because of exits and entries and crowd turnover, we often went well beyond the rated capacity. For example, Palladium was rated for a 6,500-person occupancy, but we once did 9,200 entries on a single night, a record for my career as a club owner.

We crunched the numbers once, years ago, and estimated that twenty million people have passed through the doors of my clubs at one time or another.

I made a lot of money, but this is why my clubs lasted so many years. I threw a lot of money back into production every night, man. The club was reinvented every night depending on the crowd. Sunday night, they had Rock-N-Roll Church, which lasted years. Even the lighting and all the staff were obviously different than it would’ve been for a gay night. Every detail was thought out: how do you make this a palpable experience for the crowd that you’re drawing that night?

With the Disco 2000 night at Limelight, you essentially provided a space for the club kids, like Michael Alig, to fully express themselves. What do you remember about the club kid movement?

The LGBT community back then was not nearly as tolerated as it is today, and it’s really unfortunate that that whole club kid movement – and a lot of them were just kids looking to find their own way in life. It’s really unfortunate that that whole movement got tainted by Michael Alig and then the death of Angel [Melendez]. Any time you think of club kids, you think “Oh, Michael Alig, they’re all degenerates and deviants and this and that.” And they weren’t. A lot of them were aspiring designers, clothing designers or graphic artists or whatever. I remember everybody from Mugler to Jean Paul Gaultier coming into the clubs, and then the next season, you would see the clothes that the kids were wearing [on the runway], only done in better fabrics or cuter accessories.

Have you been in touch with Michael Alig at all recently?

No. And I never will. Michael is a talented person that crossed over to heroin. I never had friends or acquaintances that were into heroin. I didn’t know he was doing heroin. And then we let him go, and he did that killing thing or whatever. Listen, he paid his debt to society, I don’t wish him ill by any means, but he burnt me. I didn’t see that documentary you were talking about, but I did see Party Monster, and even in that movie, the James St. James character [played by Seth Green] says, “How could you have done this to Peter?” I was good to him.

I’m wondering if you have any stories about the Pussy Posse… Leonardo DiCaprio, David Blaine, that group.

Well yeah, I’ve got stories, but I’m never gonna disclose them. Leonardo used to come to the clubs a lot. All of a sudden, he’s wearing a lot of lip rings. We had [Communion] goth nights – was he influenced by that? I can’t say for sure, but he was never a headache, let’s put it that way. He always went in there and had fun and never made his importance be a factor in how he was treated. He was cool.

Do you know what your clubs are now? I think Palladium is an NYU cafeteria.

It’s funny, and this I get gratification from. The Palladium building is still called Palladium, and is an NYU dorm. The Limelight will always be referred to as the Limelight building, regardless of what’s in there. It’s almost like a landmark. I’m exaggerating a little bit, but, like the Chrysler building, everybody knows the Limelight building is on the corner of Sixth and 20th. Club USA is now a W hotel. I get gratification from the impact that those buildings, for whatever years I occupied them, are now branded not by me, by society, New Yorkers, as the Limelight building or the Tunnel building.

If you could go back and revisit any moment or period of your career, what part would you return to?

Well, 1995 – I had executive produced A Bronx Tale, and I’d done another movie called Faithful with Chaz, Cher, and Ryan O’Neal, and the natural progression for me was to either go into movies, or do what Eric Goode or Schraeger and that bunch did, which was go into hotels. If I could do it over again, once I was acquitted in ’96, or ’98, I should’ve just left New York. I was much more materially driven years ago than I am now. I’m looking just for comfort and security now, which I think I have.