Crossed Paths: Morgan Simpson & Pa Salieu

Crossed Paths:

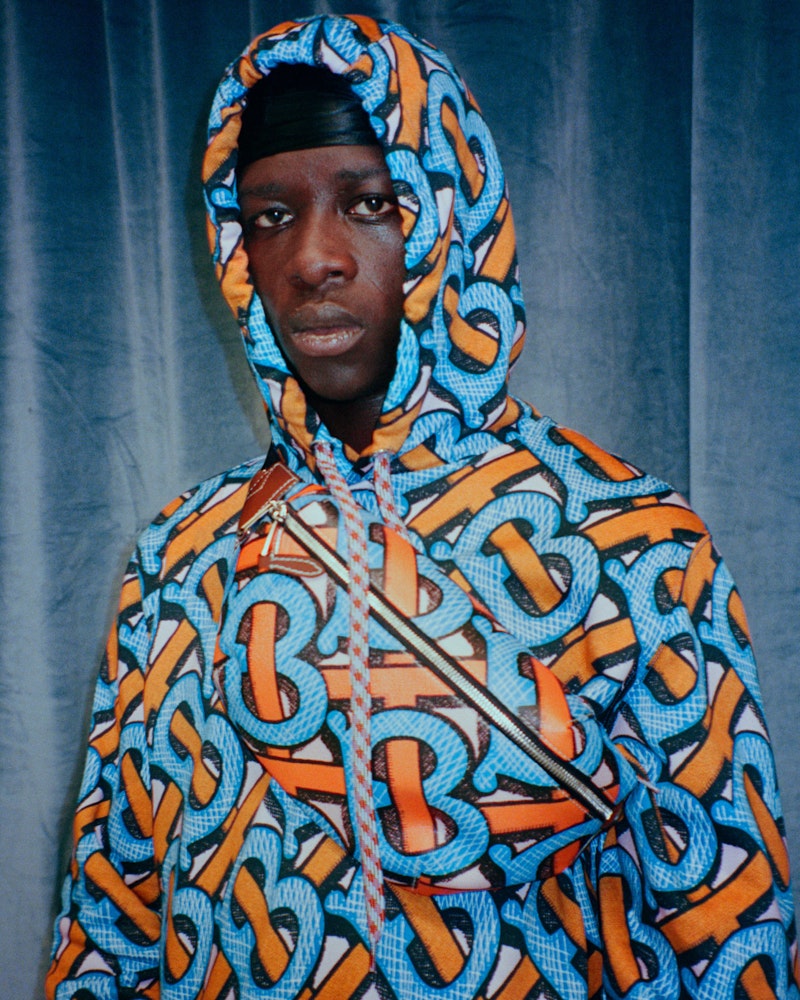

Pa Salieu

The rapper recalls his childhood years in Gambia, the culture shock of growing up in Coventry, and discovering his voice as an artist. He is one of the most compelling new artists in the UK scene. Music freed him.

As told to: Lynette Nylander

I was born in Slough, but I don’t remember anything about it. I remember being in Gambia. I got sent to Gambia before I was even two. I had never even seen my mum before. I remember being in Serekunda, at a party and I thought she was there.

What I remember the most is always being with my grandma. Family is everything in Gambia. When we ate, we all ate together, with all the cousins. My grandma would call everyone from the neighbourhood to come eat. You know what I’m saying?

One time, we even had a Kankurang. My grandfather had a farm. We had chicken running around. And we had a mosque on site and at a young age I finished the Quran. I wouldn’t have done that in the UK.

My auntie was a huge influence on me in Gambia. She’s a folk singer but she’s a crazy business person too! When she came to England, she would come buy stuff, send it back home and sell it. She has a little shop. When I was in Gambia she used to look after me too. It’s like my grandma’s sister. She goes all around the world singing. She’s sick, man.

She is a big inspiration to me. It’s about the ancestors. Who you are. That’s music. You know what I’m saying? The story of you. That is music.

It was just beautiful growing up like that. I used to be weird about it with my mum sometimes when I was a yout’. I didn’t understand why I got sent to Gambia for so long? Obviously I never knew the circumstances, why she had to, you know what I’m saying? But it was a blessing that she did. And I swear to God, fam, I know about myself. I know about my culture, my past.

You don’t know yourself if you don’t know your past.

I came back to England when I was eight or nine. Then I lived in Coventry. Coventry’s a weird place. There’s just different hoods everywhere. It’s just ends. Hillfields, where I’m from, it’s like the middle. You come from the train station. You’ll go through Frontline to go to town. It’s hella blocks. Lots of fiends.

Everyone thinks there’s only London but Coventry has hella talent. I see a lot of support. Diehard fans. Trust me, man, the culture is embracing. It’s good, man. It’s good.

“Coventry is known as the City of Peace and Reconciliation. But now violence is on the rise, there’s a lack of youth services, venues are closing down… It really does feel a lot like our youthful years.

Me and Pa Salieu worked together on one of his freestyles. He knew about where I came from and was respectful of those who had come up from the streets before him. Coventry is where Original Rude Boys come from and make a difference! I think he has a real chance to stand up and be counted.”

First time I came to England, they said my accent was too strong but I couldn’t help it. God bless it. When I came here it was weird. I got made fun of for being darker. I got kicked out of one school because I’m raised not to accept getting bullied unfortunately. They tried to put me down a year in school and say I had ADHD, but I didn’t. They put me in exclusion classes. At school, I never even thought about music. I liked English, Art, Design Technology. I would just get into trouble and be painted to be a bad guy.

They fucked it up. But I’m glad everything [happened]. Because I think everything is a journey.

Crossed Paths:

Morgan Simpson

Morgan Simpson is the driving force of black midi – a band that’s galvanised an imaginative corner of contemporary rock music. From childhood, to church, BRIT school and the Brixton music scene, drumming has helped Morgan understand himself, while collaboration has built the community around him.

As told to: Lynette Nylander

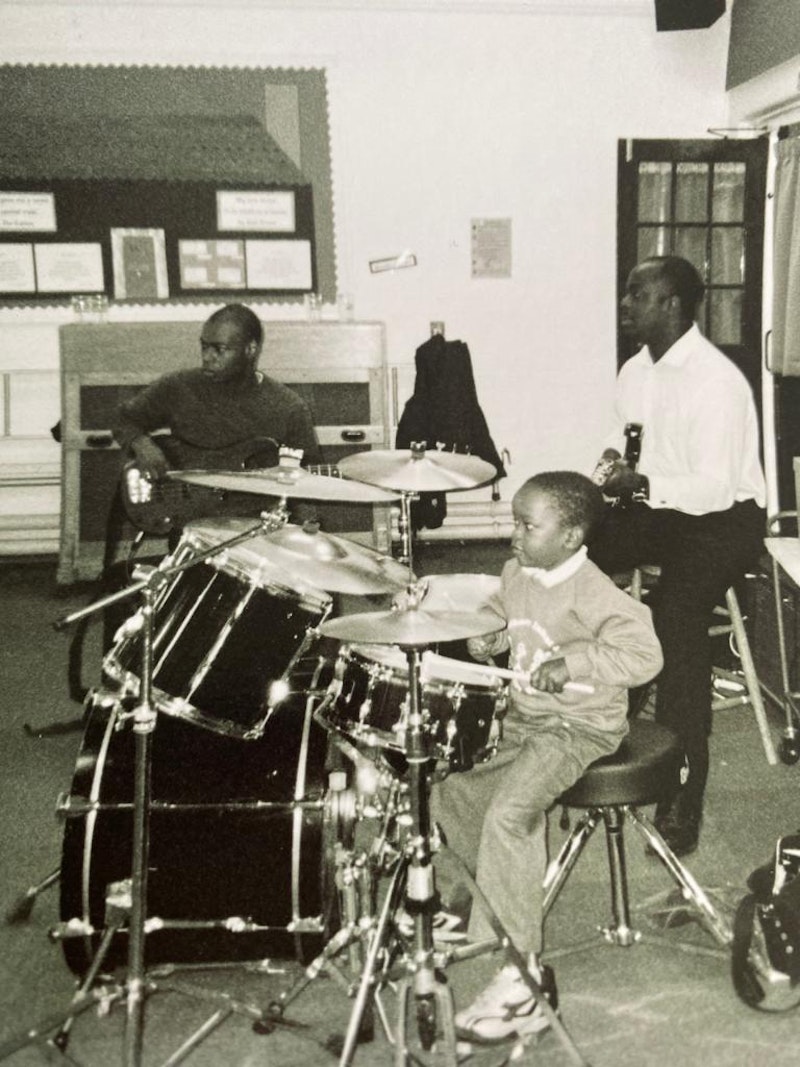

I started drumming when I was two years old.

Starting so young, it’s all I knew. But I knew that was what was meant for me.

My parents told me from the age of one. I was kind of clapping in time with what was on TV. I’d play on pots and pans and just hit things in time. In the house, we were around a lot of gospel records. People like Fred Hammonds, Kirk Franklin and Richard Smallwood. We used to have a lot of soul, R&B, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Aretha, all of that sort of stuff.

We lived in Hertfordshire and I grew up playing in church, so I think one of the earliest memories was playing in our local town centre. It was maybe one Saturday a month and we did it as outreach, just trying to connect with the community around us.

There was one time after church where everyone was kind of hanging out and having teas and coffees and biscuits and all of that. There was a perspex screen to shield some of the noise that was coming from the drums because obviously they’re loud. So they couldn’t actually see below my godfather’s neck. Everyone’s like, “What’s going on here?”. They came round and I was on his lap using my hands and he was working the feet because I was obviously too small to work a full sized kit. But that was like the very first time that they heard me play the drum kit. And they were obviously like, “Wow. Okay, he’s got it.”

As a child I was excitable, I had this ability to be an extrovert through drumming so outside of that I didn’t need to always be in the forefront. I was an introverted extrovert.

When I wasn’t doing anything music related, it was always something sports-related. I was the popular guy at school. The guy who could play drums. The guy who was really good at football. The cool black guy, innit? The kind of token going to a secondary school where I was one of five people of colour within a year group of 200 people. I was young and there were things that I would come across that weren’t necessarily okay or right that I would address. But, just being such a small minority, it means that your experiences are often just brushed under the carpet. Recent events have brought those things that have happened in the past to the surface. Hindsight has made me realise that it wasn’t as great in as many ways as I thought it was when I was a young kid.

My parents are both musicians, My dad grew up in Bedfordshire until he was seven, and then moved to Hertfordshire. My mum grew up in Clapham. They met in church camp and grew up playing music, but then they kind of transitioned into the secular world doing session work for various artists. My mum’s a vocal coach and my dad’s a guitar teacher. Then there was my sister Lauren and she’s five years older. We were the kind of family that did everything together. If me or my sister had a football game, we’d all go together. They were always there to support me. We were always encouraged to be ourselves, no matter what. That’s something I hold really, really close to my heart.

I think now I’m supposed to [have] experienced stuff that I missed when it came to socialising and everything, because I don’t always feel comfortable talking to people. I keep myself to myself. Even now, my manager said I have imposter syndrome. I think the exclusion made me pissed off and gave me fuel to prove people wrong. I used to write folklore, kinda spoken word about my life and thoughts.

Listen, music came out of nowhere but what plan B did I have? You see my first criminal record? It was when I was 18, dumb ting. I actually got caught when I was 17. It was weird, they gave me the court after my birthday. So, then I’m 18 and charged as an adult. Dumb, fam. They didn’t have to do that. I’m there thinking, “Shit, what am I doing? Have I got a [record] for the rest of my life?”

Out of nowhere, I just went to a first [studio] session and fell in love with it. I used to write notes on my phone. Write what I think, put it down to fuel my feelings. I used to record freestyles and they were shit. When I would go to the studio, I would be there for hours just repeating the same thing if it wasn’t sounding like how I heard it in my head. When a beat comes out, I hear how I’m going to sound in it. Starz was the first song I made. It’s deep on YouTube.

Femi Koleoso, drummer of Ezra Collective and Jorja Smith’s band, on being in awe of Morgan’s musicianship

I was fixated on winning ‘Young Drummer of the Year’. I actually entered when I was about eight and I think the minimum age was 12 and they just said I was too young. I waited until I was 12 and I entered two or three years in a row and didn’t win. I thought, you know what, let me just take a break. And took a year out and then came back in 2014 when I was 15 and won. It was definitely a big moment in my career. Another moment that really reaffirmed what I was meant to do. I’m really grateful to Mike Dolbear, who founded Young Drummer of the Year, because it’s a really amazing platform for young drummers and it gives people something to aspire to.

I ended up at BRIT school in 2015. I’d heard of it but I hadn’t really done much research, The deadline was five days away, so I think that just kind of goes to show as well that it’s meant to be, because I could have very easily found out too late and not gone. I am so glad I did. BRIT school was life-changing in so many ways.

“I think the exclusion gave me fuel to prove people wrong. I used to write spoken word about my life and thoughts.”

“Going from being a minority in Hertfordshire, to a diverse arts school in Croydon. It was a shock to the system, though a positive one.”

The environment, going from Hertfordshire, being a minority, to going to Croydon, going to a diverse arts school. It was like “… and breathe” moment. It was still a shock to the system, though a positive one. There was a certain level of conditioning that occurs when you’ve grown up in a place like Hertfordshire for your whole life. There was a lot I had to get my head around, certain feelings of guilt, because it’s like, “well, I shouldn’t feel like this, but I do”.

For a large majority of my childhood I felt like I didn’t really have that next level of connection with people. I think I was just in a different place, especially musically, because music was such a big part of my life. A Iot of the time I could only really talk about music to my parents, or the older generation. At BRIT, I finally had people who were into the same things I was. It was like, “Hey, this is where I’m meant to be”.

Matt and Geordie who are in black midi with me had been at BRIT before and me and Cameron joined in Year 12. In our year, there were only 45 people. Everyone knew everyone.

So we were all mates, we’d have the same classes, be in the same group for live performances. And very slowly over time, I guess we started forming a musical bonding. Geordie and I formed a connection because we took a similar route on the way to BRIT School. We’d get the Victoria Line to Victoria station, and get the train out to Croydon for school. We just ended up talking and hanging out, talking about music. Our shared love of jazz fusion bands, like Weather Report, Chick Corea and Return to Forever.

Me and Geordie started staying behind after school, booked a rehearsal room and just started to jam out, just me and him, it was a lot of fun. That wasn’t something that I had really done before, just playing with a guitarist. Separately as well, Geordie and Matt were doing guitar jams that were pretty ambient, soundscape‑y jams, which I overheard walking past rehearsal rooms a few times. And I thought “Oh, that sounds cool”.

So we started making music together.

In 2016, we got some material together and recorded it in a studio back in Hertfordshire, it was the old drum teacher of mine, a guy called Andy Theakstone, he’s a legend and played a crucial part in the earlier parts of my life. So we went there in the summer of 2016 and recorded a few tunes.

Tim Perry – booker at the Brixton Windmill venue – recalls black midi’s breakthrough

It wasn’t until summer of 2017 when we finished BRIT and Cameron came into the picture and technically joined as the bass player. We began emailing a load of venues in London to get a gig outside of the BRIT School circle. It transpired that the only venue that got back to us was the Windmill in Brixton, hence our first gig to place there a few weeks later. Feels like yesterday.

We called ourselves black midi – named after a Japanese phenomenon where people do remixes of songs of their choice and basically alter and remix them to the point where they are almost unrecognisable.

There were only ten people at our first gig, but then slowly they would keep selling out. Tim Perry, the booker at the Windmill, soon gave us a residency. I think it’s destiny. There was such great music coming out of The Windmill at the time. Black Country, New Road, Squid, Jockstrap. Georgia [Ellery, of Jockstrap and Black Country, New Road] is now on a lot of the same bills as us now. She’s an amazing artist.

Georgia Ellery on the feeling of community within the London band scene

There was hype around us but we were careful not to get caught up in that. Hype can come and go, and you never hear from them again. So we were adamant in the sense that we weren’t going to be dictated by labels really.

The Speedy Wunderground label is run by a guy named Dan Carey, who produced our first record Schlagenheim. We came across him via Tim in The Windmill of course. We ended up making [debut single] Bmbmbm in his studio in Streatham. Everything moved so quickly. At the same time the single came out, we decided to sign with Rough Trade, who really got us and what we were about. Then we began working with Dan on the album, we didn’t really know producer-wise who we wanted to go with, because we hadn’t really experienced many producers, and recorded the album in three weeks. Dan is just a really cool, humble guy, and it made things so much easier in the studio.

I was intrigued every time I went to a studio, I’d try and go as much as I could. I would connect with people. And they just give me a chance, shout out to everyone that gave me a chance. “Come to my studio. I’ve got a session there.” I would get out of college and go to London from Coventry

Producer and collaborator Kwes Darko on Pa’s perspective

Frontline I made two years ago. I was just at the studio with the mandem and got a call from my man Jevon about coming to the studio. I had come from the Frontline that day and it just came out. I dunno, I just felt it and I hummed what I want to do and used my voice as an instrument. Frontline is the strip where all the action is. The shops, the road where all the shit goes down. I feel like it’s relatable because they are everywhere in the country.

When my best friend AP got killed, the day he died, an hour before, he must have sent my video to GRM Daily. We didn’t know if they’re going to accept it or release it or not. Man, he was my best friend. He would have been my stylist.

I came out of my session from London to Coventry and I got shot. But I knew I wasn’t dying, man. Hell no. I got something I am chasing. I dunno what. There’s obstacles but there’s fate.

I just write about my life, about my friend’s life. I want people to listen to my music to hear my lyrics and just relate. Last week I was in the trap. Now I’m here. My mind is free.

Tiffany Calver – a DJ and an early supporter of Pa Salieu – speaks about his charisma and cultural identity

My mixtape is the next thing. I want to call it Send ‘Em To Coventry or Rise From The Ashes. I’ve got enough songs, I just gotta make some decisions. I wanna release it by September.

People are saying things are moving so quickly but I don’t even focus on that. I am just going on learning and listening. The real success is being able to look after my mum, my family. I ain’t really bothered about what car, about being middle class or top class. I believe I was raised richer than most people, trust me. My mother taught me something very rich.

I wanna build schools, change lives, go back to Gambia and buy land. I wanna travel too. Go to Mexico, Australia and Canada and chill with the local people there. I’ll go and show respect to everybody. Everyone is going to get treated the same from me. I dunno, music is some big puzzle I’m figuring out. It’s all been crazy.

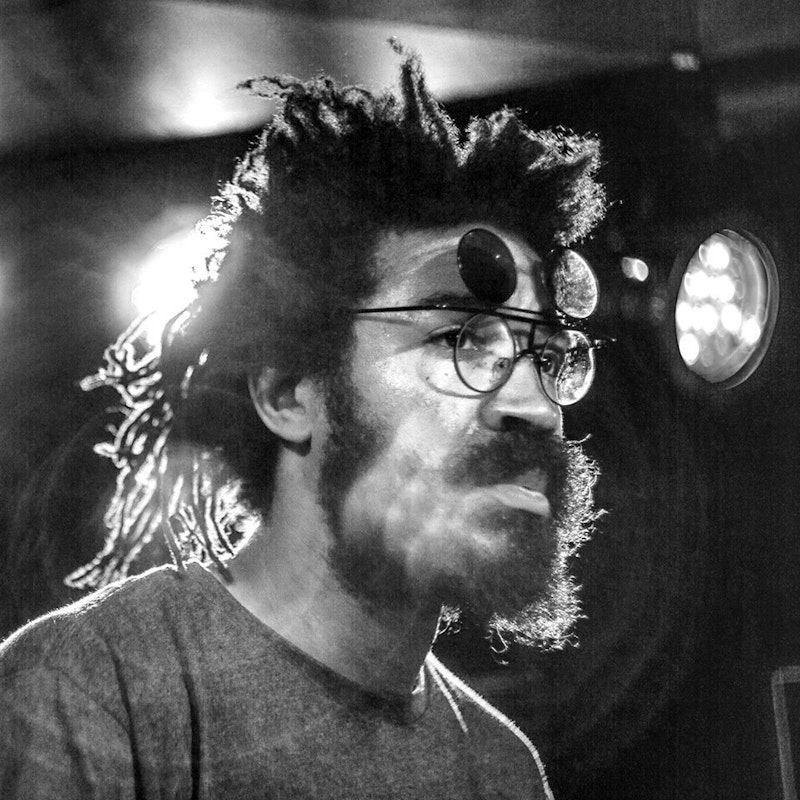

Multi-instrumentalist Wu-Lu on early impressions of Morgan

There’s no way of predicting how something’s going to be received. It was just amazing putting out this record that people loved, and then touring all over the world, which is amazing at such a young age. I mean, we were all 18, 19 at the time.

We got some people to do remixes as well. We got Kwake Bass, who is like a legend, basically like an older brother. He saw videos of me performing and asked if I would want to do a session. A few years later, he hit me up because they do a lot of really amazing work with young people, and giving them exposure to the arts. He asked me, Miles, aka Wu-Lu, and Moses Boyd to be the three special guests.

Kwake has his own voice and vocabulary and language on the drums. Both him and Wu-Lu are like twins, yin and yang. It’s honestly like having big brothers, in terms of just people who I would turn to when I’ve got questions, or I’m just going through something. People whose hearts are just full of love and nothing else.

Femi Koleoso has inspired me a lot too. Another young Black man in a similar position. We hung out a bit at a master jam session at Glastonbury last year. He’s going to do something that’s super inspiring.

Collaborator Kwake Bass on being inspired by Morgan

Community is very important to me. If you look at any sort of movement, or scene within the arts world, there’s always a community behind that. It’s never just a few people who are just anomalies who just come out and do these really cool things. There’s always a community behind it. The Windmill is a perfect example, there’s not many places like that anymore.

I think for the band I think it’s just really trying to push ourselves as musicians but also people, and just create art that’s really true to ourselves and that can speak to people in times of hardship.

From a very young age, I’ve always wanted to grow up and just wanted to do what I wanted to do. For me, it’s definitely a lot more than just music. It’s a lot more than just being in a band. It’s about influence, influencing people and contributing to a change for good. Yeah, that’s the vibe.