Dead Man’s Phone and the difficulty of anti-racist cop games

Electric Noir’s slick BAFTA-nominated whodunnit puts police discrimination against British Black men under the spotlight, but has a few blindspots of its own.

Culture

Words: Edwin Evans-Thirlwell

In 2012, the London Metropolitan Police launched the “Gangs Matrix”, a database of suspected gang members. Designed to identify potential violent offenders in advance, the database colour-codes individuals as “gang nominals” based not just on arrest or conviction records but online activities – some perfectly innocuous – from using certain slang on Facebook to watching grime videos on YouTube.

As Amnesty International concludes in a 2020 report, the Matrix is “racially discriminatory” if not “intentionally racist” because it disproportionately targets Black men and boys, many of whom have no history of violent crime. It’s also, of course, a serious invasion of privacy. Providing they obtain a warrant, officers using the Matrix are empowered to gather information covertly by creating false accounts and even befriending suspects.

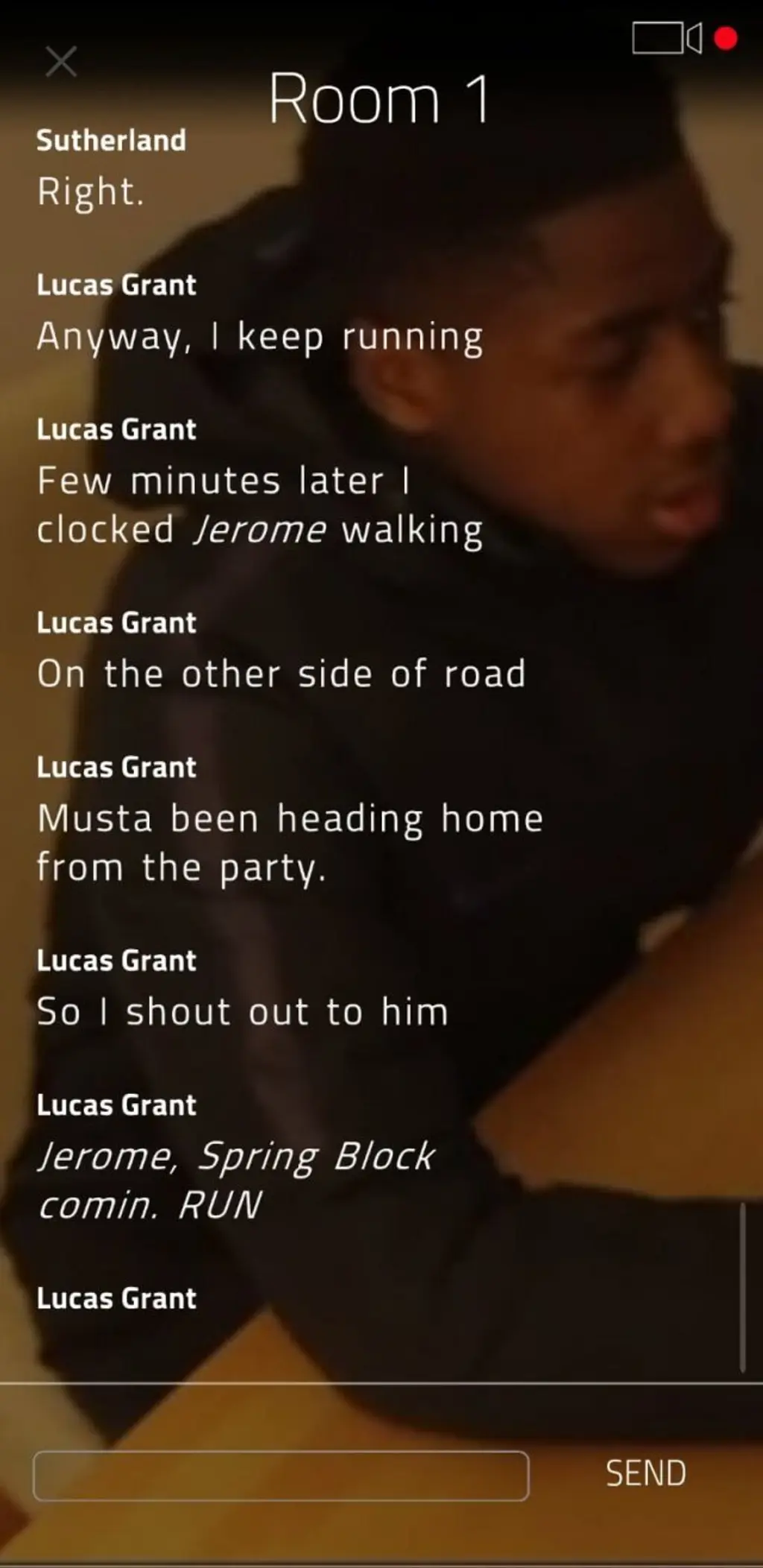

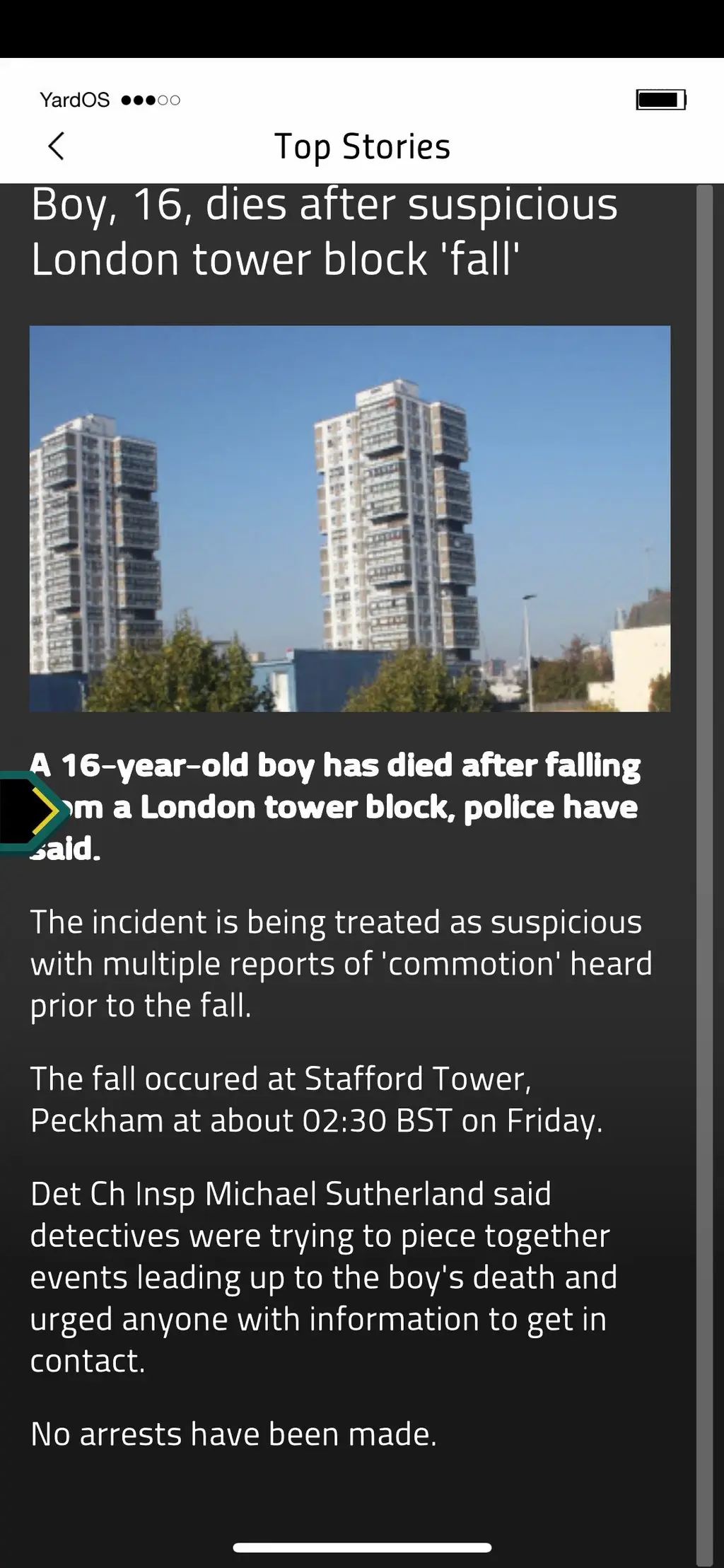

Dead Man’s Phone, a whodunnit mobile game developed by London-based studio Electric Noir, in which you play a detective investigating the murder of Jerome Jacobs, a Black teenager from Peckham, puts a positive spin on this. It suggests that the surveillance apparatus can be a platform for constructive conversations. It’s a game of two halves: on the one hand, you liaise with your Scotland Yard team, including real-life ex-homicide detective Sim Cryer, to process evidence and bring in witnesses for interrogation. On the other, you comb through the victim’s phone, studying chat threads, photos, videos, live location data, and even his music playlist for clues.

[Warning: spoilers from this point on.]

The phone’s social accounts are still active, and at one stage, you see Jerome’s friends talking to each other about taking vengeance on a possible culprit. Posting with the murdered boy’s username, you intervene to warn them off. The group is horrified – Jerome’s grisly digital resurrection exceeds all their worst suspicions about police snooping. But the shock is fleeting: they soon agree to collaborate with you in your investigation, tracing what appears to be a “gang” killing to an instance of racist police profiling.

Its macabre premise notwithstanding, Dead Man’s Phone – which has been nominated for a BAFTA Mobile Game 2020 Award – is an often-useful account of bigotry and discrimination in UK policing. Fed to you as a slick mixture of text chats, simulated phone calls and live-action footage, the story challenges “gang” stereotypes and investigates how prejudices are revealed by perceptions about language, with one twist hinging on a single word out of place. It portrays stop and search as a racist practice, and bluntly dismantles the association of drill music with violent crime.

It also, however, attempts to foster mutual understanding between the police and the policed, drawing on its cast’s very different experiences of police work in the wild. “We all wanted to tell this story, and we wanted to tell it honestly, without compromising it, without watering it down,” says studio co-founder and narrative designer Nihal Tharoor. “Some of our actors had been on the end of this kind of racial profiling in their lives – they were very passionate about getting this out.” While the overall interpretation is naturally up to the player, Dead Man’s Phone is not, Tharoor adds, intended to paint all cops as racist. Make the right choices, and you’ll not only identify the killer but earn the respect of Jerome’s friends, with one boy noting that “there’s good feds and there’s bad feds and you’ve gotta keep ur eyes open for both”.

This conclusion can’t help but sabotage the game. As Black Resistance to British Policing author Dr. Adam Elliott-Cooper explains, it continues a pattern of treating racism as an individual choice, rather than a pervasive injustice woven into our entire system of law and order. “What we know is that Black people are more likely to experience excessive use of force, are more likely to be stopped and searched and detained and charged because of institutional racism, not because of ‘bad apples’ in the police.”

Another more insidious problem is that the game’s narrative frame is fatally one-sided. In telling its story through a police surveillance apparatus, it seems to “not only justify but see this surveillance from the view of the police, rather than the people who are monitored by this expansion of state power,” Elliott-Cooper adds. Dead Man’s Phone’s script might centre the predicaments of Black teenagers in a racist country, but as a way of experiencing a story, it encourages you to identify with the enforcers spying on them.

Your understanding of the characters is mediated by the surrounding “YardOS” interface and by questions of procedure. The script doesn’t present these structures as wholly trustworthy but it doesn’t seriously interrogate how they encourage you to see the world.

As with many a socially aware cop tale, Electric Noir’s good intentions seem hamstrung here by its status as a whodunnit – a genre that may be critical of, but is fundamentally reliant on, the figure of the police investigator as a means of organising the narrative, bringing order to chaos. “I don’t really see how else you would tell these stories,” Tharoor says, when asked whether the developer considered casting the player as somebody other than a detective, adding that the “outsider” perspective is a better fit for a videogame.

To insist that only police themselves are equipped to explore the problem of discriminatory policing risks turning Dead Man’s Phone into copaganda, for all its examination of racist profiling and stop and search. But the game itself contradicts Tharoor: you make the most progress in the case by putting aside your role and revealing yourself to the kids you’re monitoring. While the implications of this are left unexplored, it teeters on the edge of being an argument for defunding and dismantling. Given the dramatic expansion of UK police powers over the past two decades, and the on-going failure of the police to tackle its own culture of prejudice, it’s important for anti-racist art to build on such departures rather than defaulting to the cop’s eye-view.