It’s cool to be awkward

Gen Z are the most online generation yet. Is it time they embraced IRL interactions and all its accompanying embarrassment?

In partnership with Hinge

Words: Sahir Ahmed

Photography: Matthew Weinberger

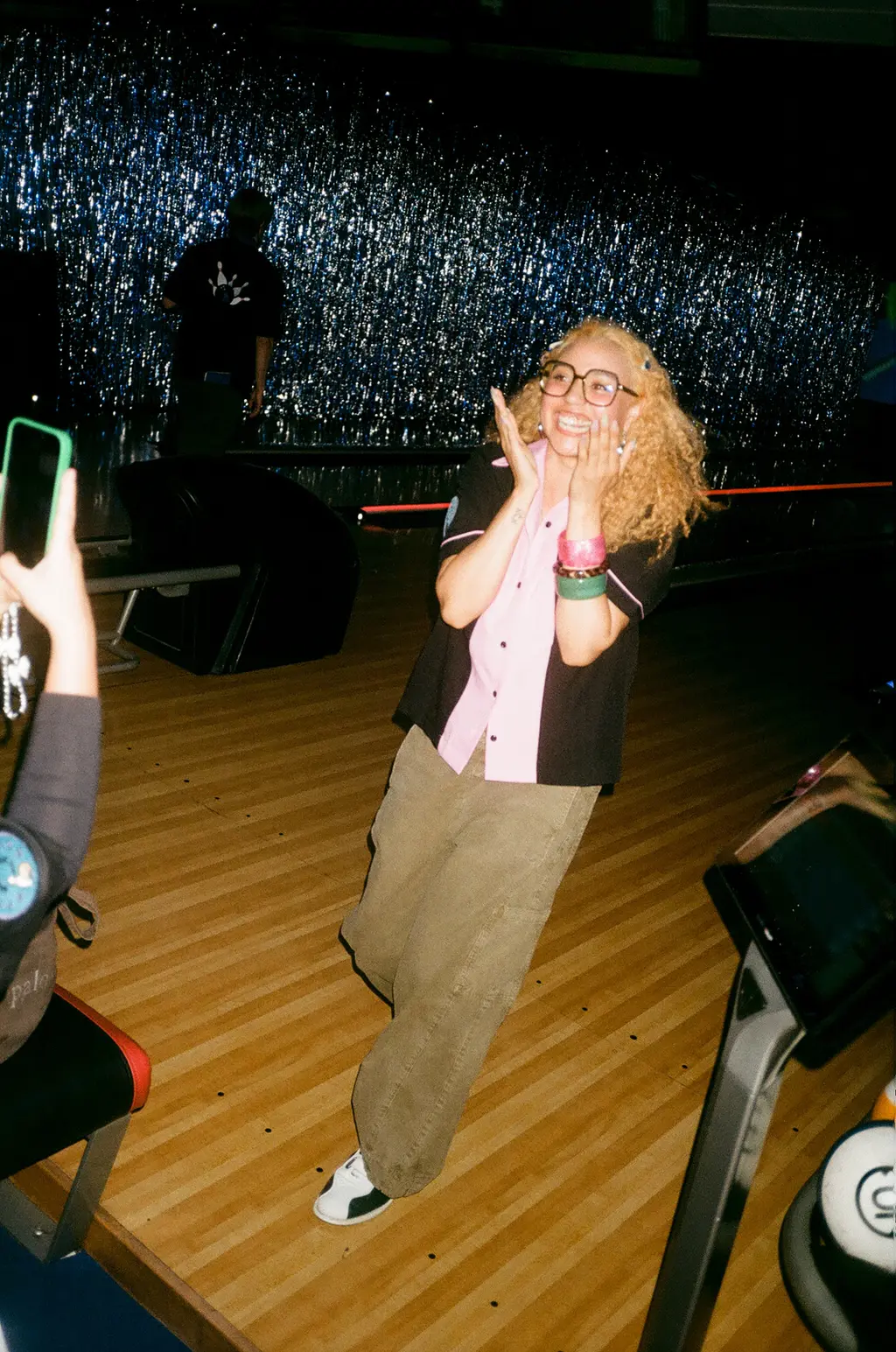

By 4pm on Sunday 7th September, Melody Lanes is packed. Bowling pins crack, cups of cheap beer sweat and tinsel shivers under the air con. Nobody’s glued to their phone, which in New York City is about as rare as an apartment under $2,000 (about £1,480).

Perfectly Imperfect – the scrappy “social magazine” that began as a Substack newsletter in 2020 before growing into PI.FYI, an anti-algorithm app where over 80,000 users swap recs on everything from toothpaste to Andrei Tarkovsky – has teamed up with Hinge as part of the dating app’s One More Hour initiative. The latter supports spaces and groups where youth can find community IRL. Tonight that means a raffle, gumballs complete with fortune-cookie-like prompts to push conversations beyond small talk, a Shy’s Burgers pop-up, and prizes such as “Most Dramatic Gutterball.”

On the mic is Peyton Dix, co-host of the viral podcast Lemme Say This. MGNA Crrrta, the NYC electro-pop duo are blasting through the speakers. Everyone, with varying degrees of seriousness, pretends that bowling is the sole focus of the evening.

This isn’t Perfectly Imperfect’s first rodeo. Just the night before, the team had filled music venue Baby’s All Right with a host of nu-blog faces, all sporting name tags that bore their PI.FY handles. Even @taterhole – one of the platform’s most famous posters – flew in from Cleveland. Tonight, she’s here too. Her bio quotes Gore Vidal (“tremendous hater”), but in person, it’s all love.

At the bar, I ask for a Coke. The bartender hands me a foreign bottle. “You’ve never heard of Boylan’s creme soda?” he asks, eyebrows raised. “Are you from the East Coast?” I am but Boylan’s has never crossed my radar. I flash a polite lie: “Of course I know it,” then switch to ginger ale. Sometimes you lie and don’t know why. Awkward.

Boomers and Gen X‑ers – bless their polo-collared souls – treated awkwardness like it was a social death. Characters like Brian Johnson in The Breakfast Club (1985) embodied this dweeby, shrinking kind of awkward. For millennials, awkwardness hit an inbetween phase. For some, it was quirky and alt, a Juno (2007) brand of awkward.

Internet personality Clara Perlmutter, who I spot sipping a soda, puts it in pop-rock terms: “In the Weezer Beverly Hills [2005] era, everyone was obsessed with nerdy men, like these intellectual hipster dudes wearing glasses and little sweater vests.”

She’s right: by the mid-2000s, even “loser rock” had gone mainstream. Beverly Hills became one of Weezer’s biggest hits, earning a Grammy for Best Rock Song in 2006. It meant that awkwardness could be monetised to a degree, although it wasn’t quite status quo.

Awkwardness was still treated as pathetic, abject – just think about the endless humiliation of Superbad’s Seth and Evan (2007) – in many cases. It existed in the liminal space between self-flagellation and self-branding. By the early 2010s, Tumblr and early Instagram aestheticised that tension into moodboards for a fringe group of indie types.

Then came a generation raised with the internet from the start. Where millennials learned to toggle between digital and physical worlds, Gen Z never knew them as separate. Born between 1997 and 2012, most grew up on platforms like YouTube and Snapchat, later graduating to TikTok. With TikTok, a social media network rewarding content that looks authentic even if it isn’t – shaky videos, “get ready with me” monologues, unhinged rants and mukbangs (food-eating broadcasts) – Gen Z’s online fluency turned awkwardness into a lingua franca.

But fluency breeds fatigue. The same generation that perfected the art of digital self-curation is now uneasy with it. In the UK, almost two thirds of people aged 16 to 24 think social media does more harm than good to young people, and roughly four in five say they’d keep their own kids away from it, per a report released in March by thinktank, The New Britain Project. Most report feeling lonely or anxious about meeting people offline, according to Hinge. The app also states that, compared to former generations, today’s young adults get 1,000 fewer hours of in-person connection each year.

This exhaustion has begun to reshape culture offline. This year, in London, the Offline Club regularly sold out “digital detox” nights where attendees lock away their phones, play games, and talk to strangers. Considering how many people are here tonight, it’s clear that there’s an appetite for awkward, analogue encounters.

Even still, awkwardness has always had its icons. @taterhole, a baby millennial aged 30, reminds me of a 2010s Kristen Stewart: “The most awkward, terrible vibes of all time,” she says. “I idolised her growing up because I was like, ‘She’s just like me for real.’” On Tumblr, gifs of Stewart’s eye-rolls and hair tucks made her a reluctant poster girl for awkwardness, even as gossip tabloids picked on her. The difference is that then it was niche – a fandom among kids who saw it in themselves.

“Awkwardness is what happens when we are not in performance mode”

Moe Ari Brown, Hinge’s love and connection expert

Since, it has crossed over into the mainstream – IRL and URL – reframed as confidence in being uncomposed: Lorde’s oversharing in Virgin (2025), Emma Chamberlain’s self-deprecating humor, Jacob Elordi being goofy AF as he arrives on the Venice red carpet. Even Love Island’s latest record-breaking US season became a hit not for its hookups but its contestants who were more adept in emotional vulnerability than in keeping up appearances. What was once a liability – crying, confessing doubt, even talking about long-term commitment – is now aspirational.

“Awkwardness is what happens when we are not in performance mode,” Moe Ari Brown, Hinge’s love and connection expert, explains. They call it “radical authenticity”: the ability to be yourself regardless of who you’re with or what you’re doing.

Back at the lanes, ginger ale in one hand and a half-empty bag of sweets in the other, I find the bin and toss the remaining uneaten treats. “Did you just throw out Smarties?” a voice calls out from the ether. Marquis, 22, dives toward the bin as though saving treasure from certain doom. “That was offensive,” they quip, discovering the pack bobbing in a half-full cup. I feel flustered and apologise. We both laugh, then we’re talking. Sometimes the embarrassing moment is the introduction.

When I ask if awkwardness is cool now, Marquis pauses, then points to Audrey Hobert, a rising pop musician whose debut album Who’s the Clown? (2025) is the epitome of “to be cringe is to be free.” Coincidentally, one of the tracks, titled Bowling Alley, sees Audrey drag herself to a party she nearly skips, at a venue much like this one – she ends up hitting a strike.

The night winds down. I leave Melody Lanes. Outside, people spill onto the sidewalk. I dig in my pocket and instead of my phone, pull out a lone Smartie – an ode to my awkward encounter.