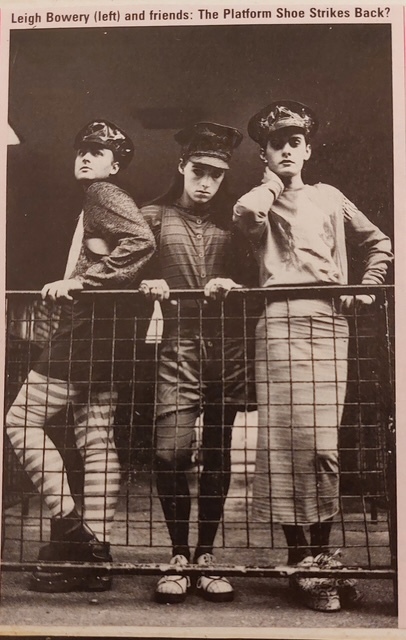

We Three Kings: the story behind Leigh Bowery’s New Glitterati

Photography by Dave Swindells, 1987

As the Tate retrospective has come to a close, one of Bowery's earliest friends and collaborators, David Walls, reflects on his complex relationship with the provocateur.

Culture

Words: David Walls

Crossing the Millennium Bridge from St Paul’s to Tate Modern on a sunny March afternoon, I became conscious of a parade of Baby Boomers and Gen Xers of all genders and none walking alongside me. There were wonky fringes, borderline theatrical make-up, asymmetric hems, extravagant costume jewellery and bizarre arty eyewear – some had the whole caboodle, which made me feel distinctly normal and sartorially understated. What we had in common, though, was our goal: the fashion/art shrine of the Gallery’s Leigh Bowery! exhibition.

For some fashion pilgrims, this would be their first encounter with Leigh. It was also my first time attending an exhibition or event about him, but like others I had a good idea of what to expect: outrageous costumes, films and photos of Leigh performing one of his attention-grabbing scatological or birthing performances, Fergus Greer’s photography, Michael Clarke’s choreography and, of course, paintings by Lucian Freud.

The exhibition’s emphasis would be on Leigh’s creativity, influence, disinhibition and ability to shock, even now, more than 30 years after his death. In contrast to this mainstream celebration of his life, when he died in 1994 it was barely noted by the media. I recall an obituary by his closest friend, Sue Tilley, in defunct gay newspaper The Pink Paper and a few notices in nationals such as The Independent (plus one in The New York Times). But memories of him soon dissipated and it was difficult to see whether and how, aside from being Freud’s model, Leigh’s legacy would be appreciated or understood by future generations.

In the 21st century, as social mores have radically changed, you could be forgiven for expecting Leigh’s legacy to be cancelled. But by a combination of sidelining some of his more offensive work and interpreting what is left as art, his legacy is now flourishing. In large part, Leigh’s cultural acceptability is due to Sue Tilley (also famously a Freud model) and her entertaining romp of a biography, Leigh Bowery: The Life and Times of an Icon. So many people now feel they know Leigh through it. Sue tells the story as it happened, including all the debauchery and obnoxious behaviours (and not just Leigh’s). And, unlike the faint-hearted Tate curators, Sue does not shirk referencing his more infamous ventures: namely Raw Sewage, his Asian-inspired collection that Leigh called “A Paki in Outer Space”, clothes covered in swastikas and the misogynistic treatment of his female “slaves” (as referred to by Sue).

However, Sue’s genuine love for Leigh comes across in her manner of storytelling, a gossipy, over-the-garden-fence kind of delivery that makes Leigh more palatable: “Have you heard what that Leigh Bowery has done now?”. In doing so, he appears as a wayward, reckless, irreverent, but ultimately likeable exhibitionist; an image perhaps reinforced by his physical resemblance to bawdy TV comic Benny Hill. Leigh himself assuaged offence by employing his natural charm, quick wit, and, when engaging with the press, a slightly over-refined manner. How could such a courteous, amusing and articulate young man be such a malevolent miscreant? Over time, the realignment of Leigh’s image worked to his and other people’s advantage, and he now stands as a titan over ’80s British fashion, art and design.

My own connection with Leigh began in 1981 when we met at London’s trendiest night out, The Cha Cha Club, a Tuesday night spot behind and connected to Heaven in Charing Cross. It was hosted by the inimitable Scarlett Cannon, whose striking theatrical aesthetic was out of step with the on-trend Hard Times look.

Scarlett was a strange and exotic creature whose appearance commanded attention as she perilously sat atop a tall bar stool, greeting friends and devotees. Her look was unique and practically impossible to imitate – and she may not let you in if you tried. Nevertheless, her guise was an anomaly at the time. Most people created their own Hard Times look from an amalgam of secondhand clothes found at Flip in Covent Garden, mixed with army surplus from Laurence Corner worn with ubiquitous Johnson’s boots from Kensington Market. To give yourself a more individualised look, you would customise these clothes or make something from scratch – if you were brave or talented enough.

If the Hard Times aesthetic was not for you, there was also a revival of the 1950s silhouette. When I met Leigh, he was sporting a homemade, boxy ’50s-style suit with a bleached blonde, tousled quiff. His friends Simon and Stephen, who lived with him in Ladbroke Grove, were similarly attired, and, when not limply slouching in the shadows, smoking, they would jive together on Cha Cha’s dance floor.

I would go to Cha Cha’s with my school friend George Gallagher and our theatre student friend Kenny Miller, who had introduced us to the club and, in turn, to Leigh. Leigh was friendly, chatty and showed an interest in our clothes and what we were doing. We took a liking to each other, and, as we chatted, discovered we shared some interests and backgrounds: including a strict religious upbringing (I was a High Church Anglican and Leigh a Salvationist), were a week apart in age (he was a week older) and had both lived in Australia.

This last link was a particular surprise to me, as I had never heard an Australian talk with a “cultivated Australian” accent (which sounds a little like British RP). I had lived in Perth for two years as a child, where the accent was broader than Leigh’s home city, Melbourne, but I gradually lost any trace of it when I returned to England. Considering Leigh had only arrived in the country a year or so earlier and up until recently had been working in Burger King, it seemed anomalous that he should now speak with an English public-school accent, but I just let it pass. Leigh was polite, smartly dressed and well-scrubbed (with only the faintest hint of make-up), so it was a surprise to see him later, with a friend, screwing up a flyer on the landing overlooking the Heaven dancefloor, lighting it with a match and tossing it indiscriminately onto the dancers below. Leigh and his accomplice then quickly scuttled back into Cha Cha’s.

“The creation and demise of [Leigh’s first collection] is a story for another day, but suffice to say he learned lessons from it, including developing a resilience to criticism, an unwillingness to compromise and an ability to push further against the accepted styles and trends of the time”

Over the next few months, our friendship grew and we met regularly at Cha Cha’s and other more overtly gay clubs: Bang, Spats or Heaven at the weekend. In the early summer of 1982, Simon and Stephen moved out of Ladbroke Grove and Leigh, who was very friendly with the elderly gay landlord who lived in the basement, secured a large room on the top floor of 226 Ladbroke Grove for me. A smaller room on his landing below was let out to an evangelical gay bus driver, much to Leigh’s annoyance, as Leigh wanted the room for himself to use as a studio from which he was planning to launch his career as a bona fide fashion designer. It was with the intention to succeed as a designer in London that Leigh had left Australia midway through a fashion degree.

However, when I moved in, Leigh could barely afford his own rent, let alone take on an adjacent room. Neither of us were working, and we survived on the paltry benefits system and shoplifting. Initially, then, Leigh set up a studio in his bedsit – the “studio” consisting of one sewing machine and his wooden floor, which doubled as a cutting table. He was already making his own clothes and was planning to create a collection that would make a mark in London, but how he was going to do this was unclear.

The usual route of showing a collection as part of a graduate show was not open to Leigh, and he lacked the resources to put on a show of his own; he had no backers, no influential friends, no platform to showcase a collection. As such, he had to garner attention in another way. He decided to make clothes for himself and a coterie of friends who, when seen out together, would be noticed and appreciated by the fashion cognoscenti of London’s clubland. He might then attract a backer or, failing that, sell clothes directly to interested clubbers or, when he could afford it, rent an outlet such as those in Kensington Market.

Those who know Leigh’s backstory will already be aware that the success which launched him into the media mainstream was his collection A Paki in Outer Space (APIOS). But before this, there was an altogether different first collection that received little to no publicity and does not even get a mention in the Tate exhibition.

This first collection, Hobos, failed in part because its content lacked anything startlingly new and was overall considered too derivative of Vivienne Westwood’s Nostalgia of Mud. It was for Hobos that Leigh taught me to sew; he was a diligent teacher and I was a quick learner, but he was also fastidious and demanding, which sometimes meant taking garments apart and resewing them – on occasion he would purchase Do-Do’s (an amphetamine substitute) so we could both work through the night.

Leigh, our friend Trojan – who later became an artist – and I paraded Hobos across the nightclubs of London, but it grabbed no one’s attention. Only a couple of items did moderately well; one of these was a green tweed bolero jacket, featuring hand-stitching and potato print, that was displayed in the recent Outlaws exhibition at the Fashion and Textile Museum. It was the first item Leigh designed that was worn by a pop star – Stephen Luscombe from synth-pop group Blancmange – and was later also purchased by Jeffrey Daniel from Shalamar. The creation and demise of Hobos is a story for another day, but suffice to say Leigh learned lessons from it, including developing a resilience to criticism, an unwillingness to compromise and an ability to push further against the accepted styles and trends of the time.

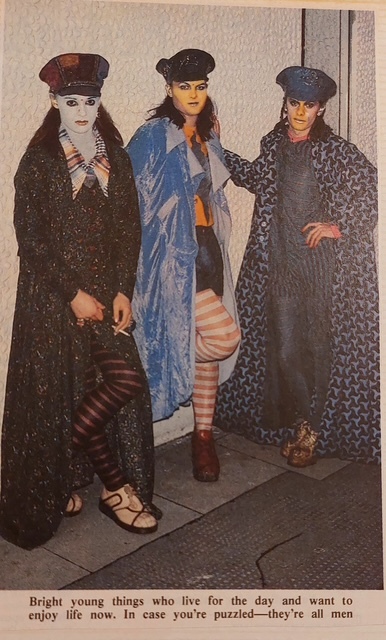

It was the creation of something new that jarred and went against the grain, making people take notice of the clothes in his second collection, APIOS was a brash blend of South Asian fabrics, Lycra, vinyl, glitter and a touch of fluorescence. All the things that were unfashionable and derided in the early 1980s found themselves in Leigh’s second inspired collection: Glam Rock, synthetic materials, loud clashing colours and a return to full face make-up for men (I recall only a few, like Boy George and DJ Tasty Tim, stuck with the maquillage through the Hard Times era). The fact that these outré, outdated fashions and fabrics were so readily dismissed also made them more easily available and affordable. It was quite easy to pick up original, secondhand ’70s platforms and synthetic fabrics in Portobello Market and Brick Lane – my favourite snakeskin platforms were only a couple of quid!

The collection needed an appellative that would encapsulate the look and as I recall, the name came to Leigh quickly in the early stages of the collection’s development, before the clothes were even made. I was surprised that Leigh would use such a derogatory pejorative – he had never expressed any racist inclinations before and had never used the “P” word in conversation, but he wanted a name that would grab attention, offend and create a baffling, almost absurd, image of a futuristic Hindu deity floating in space.

I naïvely convinced myself that Leigh’s intention was subversive wordplay, as to me the collection appeared to be an obvious visual celebration of South Asian culture, and anyone whose interest in the collection was stimulated by racism would be sorely disappointed. It should be noted that the idea of cultural appropriation was only known in small academic circles at the time and it was quite acceptable in 1983 to dress up as a Hindu deity if you wanted to.

As it turned out, the collection’s name was rarely used, even in the media, and we soon became known as the New Glitterati, New Glam or, when referencing Leigh, Trojan and I alone, The Three Kings (i.e. the Magi who followed the Star of Bethlehem that features on many Christmas cards – a name bestowed on us by Sue Tilley and the Wag Club’s Louise Neel). Looking back now, its title was unnecessary, as interest in the clothes came despite the name, not because of it. Nevertheless, it is a sad indictment of the time that it did not cause any controversy – no one I can recall ever challenged Leigh about it, not the press, the fashion industry, friends or other designers.

“It was important to Leigh to create an effect, and there was none better than a last-minute arrival at a club freshly made up when everyone else was looking slightly jaded”

By 1983, gender-fluid apparel had become fashionably acceptable and Leigh wanted me to wear the new collection’s skirt design, which was not something I’d done before or been particularly interested in, but I had no objections. Leigh himself did not want to wear the restrictive, skin-tight skirts and he felt that Trojan’s body was too boyish and slouchy to carry them off, whereas I had a naturally slim waist and wider hips (to my eternal dismay). I was happy to wear the skirts occasionally, but not all the time. In fact, often our outfits were interchangeable, and what I, Trojan or Leigh would wear one night, another would wear the next. There were only a few items that Leigh made for Trojan and I individually, as gifts, that we wore exclusively.

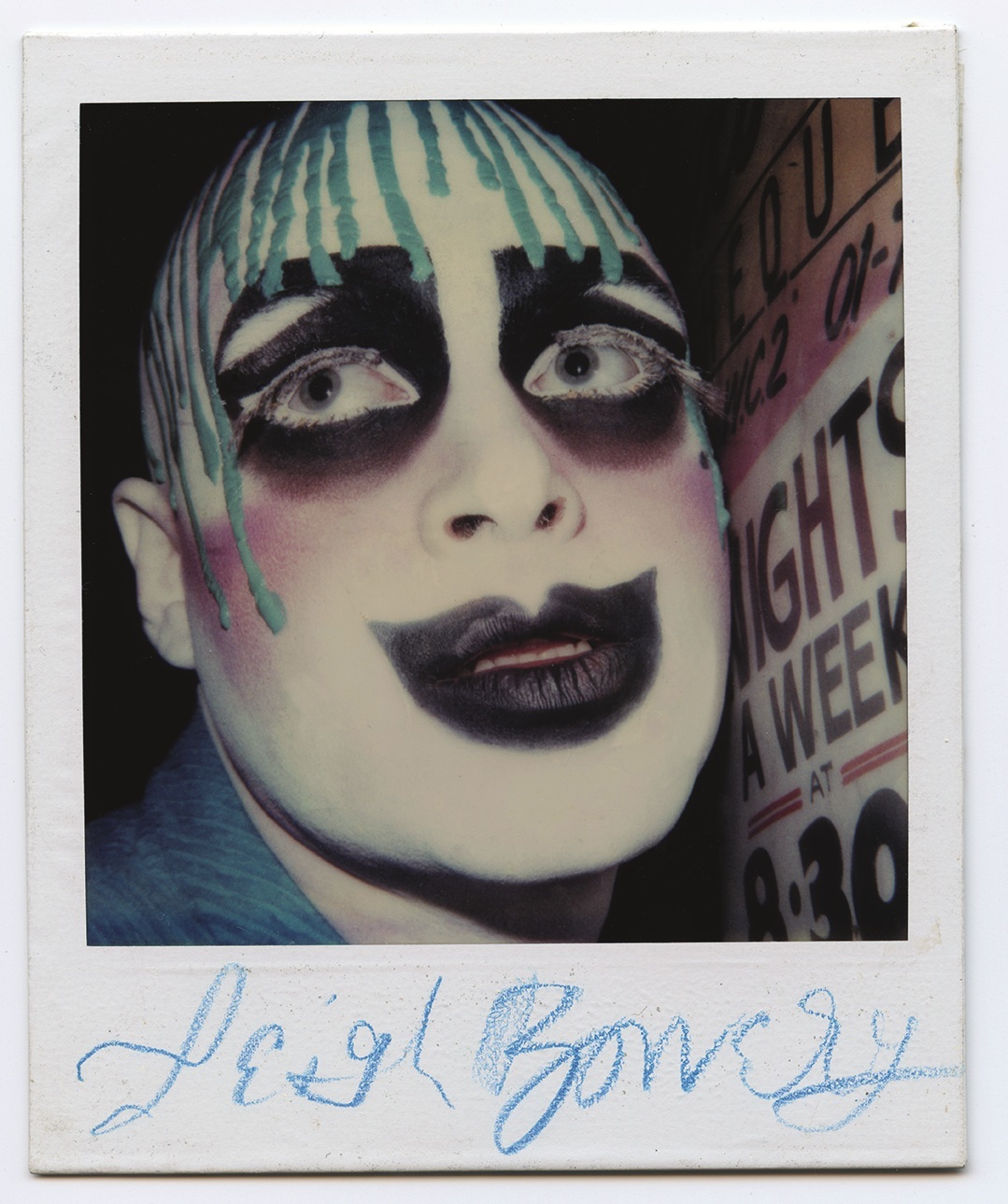

From the very beginning, Leigh was controlling about how we wore the clothes, accessories and make-up. Initially, he would do all our make-up himself, completing Trojan’s face and mine before applying his own. The make-up was quite detailed: gold or silver crescent moons and stars with liquid glitter eyebrows, blended-in eyeshadows and shading with metallic-coloured ears. This was time-consuming and meant we were usually extremely late arriving anywhere.

Nevertheless, it was important to Leigh to create an effect, and there was none better than a last-minute arrival at a club freshly made up when everyone else was looking slightly jaded. There was a triple impact with the three of us dressed in the collection and, if there were photographers around, we quickly attracted attention amidst the Hard Times crowd. Within a short space of time, we were getting the media attention that Leigh so desperately wanted and worked for.

Leigh’s face had first appeared in print on the cover of Time Out in January 1981 (a patchwork of photos of New Romantics which included Steve Strange, Stephen Linard and John Crancher; Leigh is on the bottom row, second from left), but he was not identified by name. Now, when photos started to appear in magazines, he was being name-checked as the creator of a new look. Naturally, he was thrilled, but being a controlling perfectionist, he would also over-scrutinise and often criticise the photos and the way his clothes were presented.

As he had largely styled us himself, he was happy with how Trojan and I looked, but another friend, Peter Hammond, aka Space Princess, did not always fare so well. Space was a stylist himself and loved Leigh’s clothes – he borrowed several pieces to wear for the video shoot for Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s debut single, Relax, which was released in October 1983. Space featured in the video, having styled himself with fingerless gloves, multiple strands of beads and a theatrical mask – none of which Leigh felt were true to the concept of his collection. Leigh was slightly dismissive and irritated and took little interest in the video, which was banned by the BBC in January 1984 for “obscenity” and was kept off the airwaves during the day (some DJs continued to play it on night-time shows).

On another occasion, Space appeared with us in a photo taken outside the Circus nightclub, in one of the collection’s large plastic caps (but not the clothes). There was nothing Leigh could do as Space loomed over my shoulder, smoking a cigarette, in an off-the-shoulder number. However, when the resultant photo appeared in pop magazine Number One (and later in Time Out), Leigh complained that Space was wearing his hat at a “jaunty angle” that was not to his taste.

As if to prove a point, he showed us the picture with his thumb over Space’s head and announced that the photo would be much improved if Space had not been in it. This was nothing personal: Leigh was fond of Space, who was a ball of energy and had some crazy styling ideas, and used him in a number of runway shows. But when it came to restyling his look, Leigh was very protective and didn’t welcome anyone else’s interpretation.

Apart from impromptu photo opportunities outside nightclubs, there were also some professional photoshoots where Leigh felt he might have more control, but the results of these could also be a source of disappointment. Photos taken outside Trojan’s one-bedroom council flat in Grimthorpe House, Clerkenwell appeared in young women’s magazine Honey in February 1984.

We were all living in this flat at the time, becoming local curiosities and the target of random verbal abuse – “freaks”, “queers” – from the estate’s teenagers. The photos were taken at 6am so as not to draw attention. Leigh was happy with the poses which, as interpreted to him by filmmaker John Maybury, were a reflection of our characters: Trojan was malevolent and melancholic, I was glamour-fixated, while Leigh was looking into the future, gazing at the stars. But Leigh was baffled as to why they were published in black and white when colour was so integral to the collection.

Leigh had higher expectations of a photoshoot styled by Michael Roberts for Vanity Fair, which was to be photographed by David Bailey. But the lure of nightclubs the previous evening meant we were physically exhausted and not as fresh-faced as planned. We’d slept in our clothes and just touched up the make-up before heading by taxi to the King’s Road, where we were due to meet Bailey and others. David Bailey had, of course, been a famous fashion photographer of the 1960s and early ’70s, but by the ’80s had lost some of his cachet and was eager to recapture this by photographing London’s newest young fashion things.

Michael Roberts’ concept was a staged mock walkabout by Queen Elizabeth II lookalike Jeanette Charles, who meets her young New Glitterati subjects – namely, me, Leigh, Trojan and Jane Kahn of neo-gothic Birmingham fashion label Kahn & Bell. Between the Three Kings, Jane, David Bailey and Jeanette (who some tourists thought really was the Queen), it wasn’t long before there was a throng of inquisitive admirers blocking the pavements of King’s Road. People started spilling onto the street, the traffic ground to a halt and the police quickly became involved. Much to Bailey’s annoyance, in order to allow the crowd to disperse we were all moved to the backstreets and took refuge in Brompton Cemetery, followed by the police.

Bailey decided to carry on photographing us and requested that we sit on top of the sarcophagi. This was too much for the police, who threatened to arrest him and took us aside to administer a caution for sitting on the tombs, while at the same time barely concealing their amusement at our appearance, asking, “When did the clown look become fashionable?”

Eventually, we were allowed back on the King’s Road to complete the shoot. During one final break, we went down a side street to get away from the crowds and were surprised by nightclub photographer PP Hartnett, who we knew from the clubs. He took a couple of snaps of us. When the Vanity Fair piece came out in March, it generated hardly any interest. Leigh bemoaned that the clothes were barely visible behind the snappy graphics and editorial content – another lost opportunity. Nowadays, it is the simple Hartnett snapshot that is remembered and regularly republished in Weekend magazine in 1984 and Elle in 1996.

One thing noticeable in the King’s Road photos is that Trojan had started to wear different make-up from Leigh and I. As mentioned, Leigh used to apply full face make-up on all three of us, which took a long time and created some tensions between him and us. At these times, he would often criticise us for our dependence on him, though we were quite happy to do the make-up ourselves if he gave us the tools to do it, but he didn’t quite trust us to create the look he wanted. At these times Leigh could behave like an overbearing mother, nagging and belittling us, to which we would respond in kind with childish name-calling and in-jokes – we would call him Benny (Hill), The Blob, or Doughnut (after the fat kid on ’70s TV show Here Come the Double Deckers!).

We would also mock his phoney English accent and ask him, “Leigh, why do you talk like Hamish Bowles?” Trojan took matters into his own hands one night while Leigh was applying my make-up, applying blue foundation over his own face, in an even tone, without any attempt to blend in other colours or add anything more than glittery eyebrows. Leigh was initially unsure of the overall look, but it was too late to change anything. The attention and compliments Trojan received that night increased his self-confidence and tempered Leigh’s controlling attitude.

In time, Trojan experimented further with Picasso-inspired abstract make-up, which again took Leigh by surprise and encouraged him to allow Trojan more liberties with his styling. Trojan had always had some interesting ideas and perspectives, but Leigh had previously not given them much attention. Now Leigh was starting to acknowledge and encourage Trojan’s experimental looks, he became less willing to toe Leigh’s line and became more independent.

Photography by PP Hartnett

Divisions between The Three Kings were already appearing in the autumn of 1983. In January 1984 we left Ladbroke Grove as the landlord had recruited an unbearable gay couple as rent collectors who insisted we pay the rent on time (!). They were also confrontational about what they saw as our anti-social and rowdy behaviour, so Leigh and I moved into Trojan’s council flat in Grimthorpe House. It was only a one-bedroom, and the three of us lived in the lounge so Leigh could use the bedroom to sew and store clothes.

With the addition of two kittens, it became extremely cramped and quite chaotic. When we were in Ladbroke Grove, Trojan had his own accommodation and if he stayed with us, would sleep on a sofa in the living room. But now, Leigh and Trojan shared a double bed, while I had a single at the opposite end of the room. Though I could not see anything, I could hear Trojan fending off Leigh’s unwanted advances in the night. Leigh would say that he needed the warmth of Trojan’s body in the cold bed in order to sleep and he was only being affectionate.

I had some idea of what Trojan was going through, as Leigh had no boundaries when it came to sex and anyone was game. He was very persistent and ignored rebuffs, believing that he could wear down any resistance and have his way – in Trojan’s case, he needed to supply him with drugs to do it. I was glad to have my own bed, but I felt sorry for Trojan. We had already applied to the council for an exchange for a three-bedroom flat in or out of the borough, but the waiting time was potentially quite long.

In order to expedite the transfer Trojan decided to commit arson, which was in keeping with his character – he was fascinated by murderers and criminality of all kinds, which Leigh never understood. The arson’s intention was to provide proof to the council that we were being targeted by homophobic neighbours. Trojan could be quite spontaneous and soon after deciding to commit arson, he made a comment that he was going to “do it now”, that we should “prepare for it”, which we ignored.

Trojan left Leigh and I in the lounge, went through the hall, placed a bundle of discarded cotton fabric by the front door, went outside and tossed a lit match through the letterbox. The fabric, which was somewhat damp due to the coldness of the flat, started smouldering rather than burning and the smoke quickly permeated through the hallway. Trojan’s plan was for us to douse the flames ourselves, but in our panic, and to get rid of the choking smoke, we instead picked up the bundles, ran through the lounge, and threw them out the window. The flat was on the fourth floor and the blustery wind blew them onto two trees nearby. The fabric started to burn; five minutes later the trees were engulfed in flames.

A neighbour alerted the fire brigade, who, having extinguished the fire in the trees, later turned up at our flat to investigate further. Our indoor-wear at the time was unsold ankle-length A‑line calico dresses from Leigh’s Hobos collection. Having aired the flat by the time they arrived, there was now no evidence to link the fire to us, and after some feigned surprise and pleas of ignorance, the burly firemen made a hasty but smirking retreat. A few days later, while Leigh and I were out buying more fabric, Trojan made a second, more successful attempt, scorching the front door from the outside and daubing the words “queers out” on the adjacent walls in paint stolen from Woolworths. Once this staged event was reported to Islington Council, we were offered a transfer to their neighbouring borough, Tower Hamlets, at Farrell House off Commercial Road.

“The New Glitterati look was not so new anymore. I wanted to make clothes for myself and not just be Leigh’s machinist and clothes horse”

The experience of living in Grimthorpe House was not positive for any of us and it was a relief to leave, but it had also changed our relationships. Trojan had always experimented with any drug he could get his hands on, but Leigh was never so interested and, like me, preferred alcohol. I had dabbled a little in drugs with Trojan in Ladbroke Grove, where I was for a brief period on a prescription for anti-depressants, but I found that, combined with alcohol, they just made me sleepy. Trojan would take the lion’s share and encouraged me to get repeat prescriptions long after I needed them. Once acid became widely available, both Leigh and Trojan started to take it regularly, almost every time we went out. I wasn’t interested in acid and didn’t enjoy being with them on acid at home, so I began reconnecting with other friends.

At the same time, the New Glitterati look was not so new anymore. I wanted to make clothes for myself and not just be Leigh’s machinist and clothes horse. At this point, I had lived with Leigh for two solid years and we had spent most days together morning till dusk – apart from Trojan, I don’t think anyone lived with him for so long. I didn’t mind the bitchy comments as it was part of our banter, but he was experiencing mood swings, which I put down to his increasing use of acid and perhaps frustration with me.

A distance grew between us and after a few weeks at Farrell House I wanted out. My relationship with Trojan was still cool when he wasn’t using – he confided that he found Leigh’s advances too much, that only the drugs made it bearable. I said that at least if I left, he could have a room for himself. My leaving itself was uneventful; Leigh and Trojan returned home one night on acid and a few words were said by Leigh (supposedly out of earshot) about how he would use my room when I left. I had already half packed, so it didn’t take long to collect the remainder of my belongings and exit into the night.

I stayed for a while with my old school friend George Gallagher and his partner Jimmy Payne in Finsbury Park, and it was about a week or so later when Leigh phoned to talk to me. He sounded slightly sheepish and, in a roundabout way, said sorry for the way things had turned out. I made some general comments about how it was time that I moved on anyway. He then asked if I would do him a favour, which I wasn’t expecting to hear, and do one last photoshoot with him and Trojan for THE FACE.

They had been after him for some time and he was expecting this to be the best opportunity yet. The photos were to be shot by the great Sheila Rock, so Leigh had high expectations. I asked why he didn’t just do it with Trojan, he didn’t need me in it too, and he said the editorial had already been written and I was specifically mentioned in it, so it would look odd without me. I suggested that it wasn’t that difficult to change the editorial, but he said it wasn’t that easy. This made me think that he’d already tried – I instantly recoiled and said that it would be better for both of us to have a break and I wasn’t interested in doing another photoshoot.

When the article came out in April 1984 (Issue 48), Leigh and Trojan both looked fabulous. Leigh was right – it was the best he and his New Glitterati collection had ever looked. The editorial was left unchanged and I was name-checked as “Dazzling David”.

As it turned out, that wasn’t the end of our friendship and our paths crossed many more times, such as working the cloakroom at Taboo, modelling in the Mincing Queens collection (Leigh’s third and last solo collection) and a final photoshoot to come for i‑D in October 1984 – in which Leigh returned to complaining about the poor composition and partially blamed me for it. Eventually, I left that life behind completely and only spoke with Leigh a couple of times over the phone in the last years of his life. In 1986, Trojan sadly died, aged only 21, of an overdose.

Looking back, those formative two years living with Leigh seem carefree and adventurous, but I also recognise it was a psychological rollercoaster and occasionally brought out the worst in me. I continue to look back on Leigh fondly, but for many years kept those memories at arm’s length. I chose to walk a different path and many people I know now are either unaware of Leigh or of my involvement with him.

The reappraisal of Leigh’s life and work will, I guess, preoccupy academia and the public for many years to come. Few people married shock, art, fashion and humour so successfully. His intent to divide and challenge has continued years after his death and is as much a part of his legacy as the inspiration he provides to all those who seek their identity away from the high street and in their own creativity, such as my companions on the Millennium Bridge – which is just what Leigh would have wanted.