Teenage boys’ lives are more complex than ever

(From right) Brian wears jacket and trousers _J.L-A.L_ and top and jewellery talent’s own, (middle) Jerome wears jacket and trousers JULES MONTIEL and top and jewellery talent’s own, (middle behind Jerome) Abdulai wears hat talent’s own, (left) Jahari wears jacket, top, trousers and scarf BURBERRY, (background left) Josh wears jacket VERSACE and top, trousers, shoes and jewellery talent’s own, (background right) Korie wears jacket DIESEL, trousers DRIES VAN NOTEN and top and trousers talent’s own

They've got a lot to worry about. There are exams, homework and Andrew Tate; hairstyles, football results and first kisses. But getting through boyhood unscathed isn’t a lost cause – not with this lot, at least.

Life

Words: TJ Sidhu

Photography: Alfie White

Styling: Hamish Wirgman

Taken from the autumn 24 print issue of THE FACE. Get your copy here.

It’s a miserable day in Hackney, East London. Thick pellets of rain drop onto dull pavements, the sky is murky grey and there’s a chill in the air. Brit summer, eh?

In a small studio in the corner of an industrial unit, the energy’s a little more sunny. Three teenage boys – all friends from school – are rifling through a rail of clothes, picking out hoodies, puffer jackets, baggy jeans and branded T‑shirts. There’s some sort of techno mix playing out of a speaker, and someone offers to stick the kettle on.

One of the boys, Jack, from nearby Dalston, picks out his outfit, gets changed behind a modesty curtain and emerges a few minutes later wearing a casual shirt, trousers and a pair of black leather boots that go way past the knee. The boots are a little unexpected, especially because the 15-year-old was wearing beaten-up trainers when he arrived. As he confidently strides around the room, the schoolmates he arrived with, Cormac and Evan, both 16, give nods of approval before setting off to get their photos taken.

Today we’re meeting groups of teenage boys, ranging from the tender age of 13 to the rollicking edge of 19, on the cusp of adulthood proper. We’ll be asking them what they think about all sorts of subjects, from mental health to toxic masculinity, and trying to find out whether Andrew Tate is really influencing the corridors of schools up and down the country. Other topics on the agenda: are teenage boys talking about depression? Do they know what careers they want to pursue? Do they give a crap about politics? What – in no simple terms – is the reality of being a teenage boy in 2024?

(Left) Cormac wears jacket MONCLER COLLECTION, blazer (worn underneath) JULES MONTIEL, shirt and tie TURNBULL & ASSER, trousers GUCCI and shoes FERRAGAMO, (middle) Jack wears jacket STONE ISLAND, shirt and tie TURNBULL & ASSER, trousers MONCLER COLLECTION and shoes FERRAGAMO, (right) Eben wears jacket _J.L-A.L_ , shirt VALENTINO, tie TURNBULL & ASSER, shorts GR10K, shoes ADIDAS and socks talent’s own

Once Evan, Cormac and Jack have been photographed, the trio of best mates return to the studio, chatting excitedly about the photos. All from Hackney, they met at their local state school and are just finishing Year 11, the GCSEs period teachers often refer to as the first step into adulthood (whatever that means).

Like most boys their age, they’re stressed at the prospect of this year defining the rest of their lives. But you can’t be expected to study all the time, right? “I love painting, but it’s kind of a guilty pleasure at the moment because I should be revising,” Cormac says. “The other night, I was painting some random person from a Netflix series.”

At that moment, he hears a ping and checks his phone. Jack does the same. Their attention, gone. Growing up is tough. Each generation has faced its own set of pressures. But for these teens, there’s one big difference: the entirety of their extended lives, habits and interests are scrutinised under the microscope of social media, even more so than for the half-generation before them. Teenagers are sharing their lives on Instagram, tweeting on X, getting schooled on TikTok, snapping on Snapchat and getting to know strangers on Discord. Sure, the internet can be good for a few things: making friends, finding club nights, buying and selling clothes, beating boredom with laugh-out-loud 15-second video clips.

But it’s also become an open window for cyberbullying and misogynistic revenge porn, not to mention increasing pressures on pretty much everything from having a six-pack like the boys on Love Island to owning a Rolex like Central Cee.

“My child is not having social media ’til they’re, like, 14,” says 18-year-old J. He’s sitting by a wooden picnic table with five of his college mates, all of whom grew up around here and are also part of today’s shoot. They’re into basketball and gaming, play five-a-side in their spare time and take part in their college’s debate club. For him, the dangers of social media are abundantly clear. “They’re prone to learn about all sorts of trends, you know?” he says of his peers. “Even though people are making things ‘for kids’ on iPhones, they’re not filtering out the dangers, things that they shouldn’t be thinking about, like violence or something sexual. Children are easily influenced by social media.”

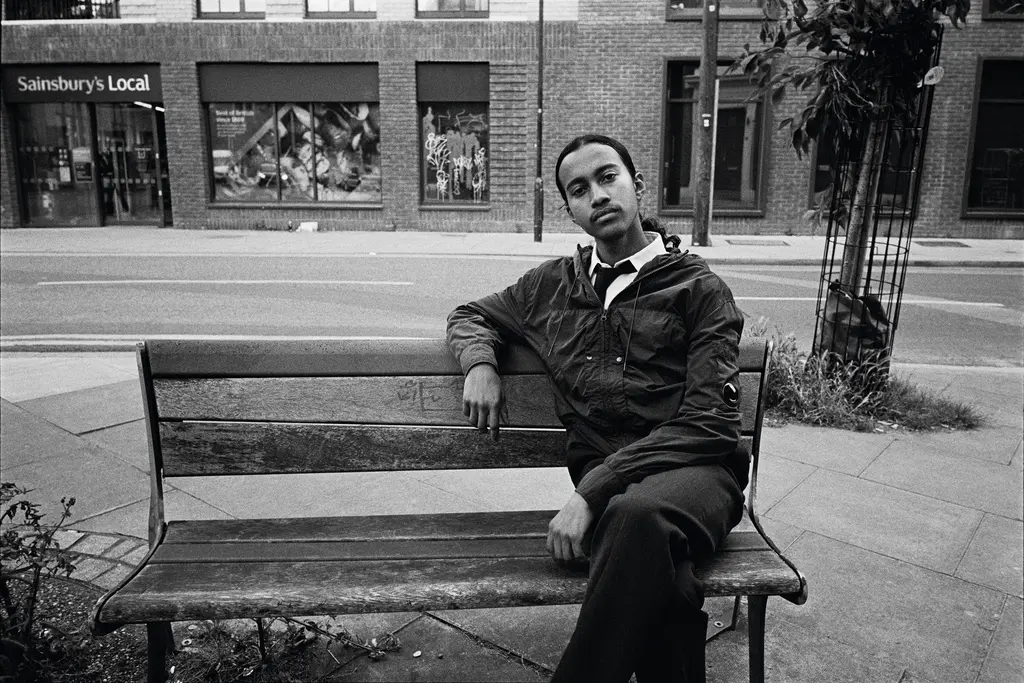

Aaron wears jacket FILA+, shirt HERMÈS, trousers Y/PROJECT and shoes talent’s own

Teen boys are also being exposed to online predators. In October 2022, Dinal De Alwis, a 16-year-old straight‑A student from Sutton, south London, was targeted by an unknown messenger who had obtained his phone number. The man, who used a VPN (virtual private network) to mask his location, threatened to send nude photographs that Dinal had sent him to Dinal’s friends and followers if he didn’t send £100. Shortly after the blackmailing attempt began, Dinal – who had recently attended a University of Cambridge open day – took his own life. His family discovered he had been thinking about doing it after logging into his Snapchat.

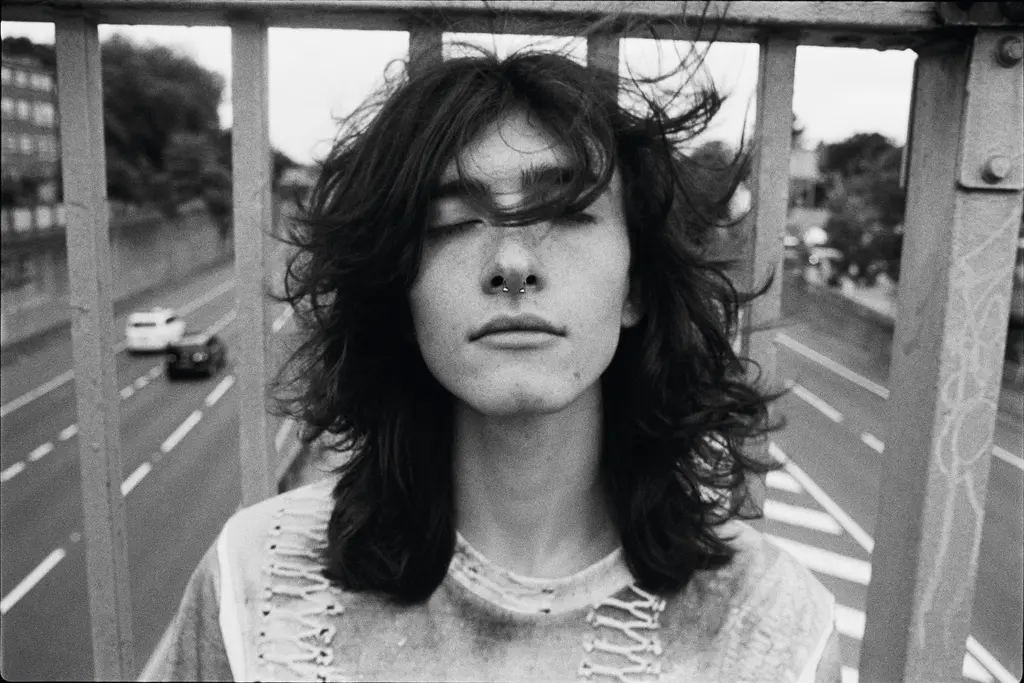

All of the boys we meet today are on social media: Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, or all three. For the most part, they use it to keep connected with friends, share a good-natured Story and follow their favourite rapper, footballer or clothing brand. But the majority know at least one person who has been affected by cyberbullying, leaked nudes or rumours being shared on various platforms. Fred is 16 and from Wandsworth, southwest London. He came out as gay at the age of 11. He speaks confidently and recently transferred from his secondary school to study visual arts at the BRIT School. While he has never been the victim of cyberbullying, he knows many people who have – particularly nude images being sent to classmates.

“There have definitely been inappropriate images shared around [at my school],” he says. “My year, especially, has quite unrestricted internet access. And I think from a young age, it can really alter someone’s perception of the world for the worse.”

Whether you’re plugged into the news or choose not to be, the world can seem pretty bleak. But Fred is optimistic about the future. He had a different experience during the lockdowns, though, when he felt the effects of negative mental health for the first time. “I had quite an intense phase of depression,” he says of a period that began when was 12. “Those are the key years of growing up – the transition from a child to a teenager. And if you’re locked inside and can’t see people, your only vice is the internet. It’s bound to not go very well.”

According to a recent study in the journal European Child + Adolescent Psychiatry, teenage boys’ mental health was more adversely affected by lockdowns than girls’. And what’s more, the impacts are less likely to improve as time goes on. As Dr Nicky Wright, a co-author of the journal and a lecturer in psychology at Manchester Metropolitan University, told The Guardian: “The key message of this is that we expect more boys to be at risk of mental health problems now than we would before [the pandemic].”

When it comes to feelings, boys have never been good at opening up. Who can blame them? We grew up with dads who told us to “man up”, and their dads said the same to them. PE teachers ordered us to “toughen up” – while running laps in the middle of sodding winter – and men who showed their emotions on the telly were called sissies and worse. Nobody seemed to learn anything, no matter how many generations passed.

Mental health is still a taboo subject for many men; it’s not often you’ll find a group of lads opening up about their anxieties down the pub. But we are starting to move past the stigma. The merits of masculinity are – thankfully – no longer pegged to beer, beards and bottling it all in.

(Left) Natthasiri wears jacket JULES MONTIEL, trousers FILA+, shoes WIRGMAN STUDIOS and T-shirt talent’s own, (right) Sasha wears jacket MONCLER COLLECTION, trousers Y/PROJECT, shoes FERRAGAMO and T-shirt, hoodie and hat talent’s own

“My friend had a pretty bad case of anxiety. He ended up dealing with it and he’s a lot better now, a lot more confident,” says Zane, a 16-year-old from Haggerston. His parents are divorced, so he lives with his mum and four sisters, and he’s currently looking for an apprenticeship. He’s keeping his options open, with potential career paths including coding or a trade such as bricklaying, plumbing or electrician work – the latter field his “idol”, his jack-of-all-trades dad, works in.

Zane admits that while the lockdowns were confusing, they didn’t weigh on his mind too much. But when his friends are in a bad way, he’s the first to check in. “If anyone’s feeling down, we always talk about it and help them out, maybe invite

them to play football. Men usually shut it away and we keep it to ourselves, but I think it’s changing a lot now.”

All of the boys we speak to are in agreement that attitudes towards mental health have moved forward – and each has friends they regularly open up to. It helps that, in the past few years, depression, anxiety and the general worries of young men have been depicted more widely in pop culture, from Channel 4 sitcom Big Boys and Lewis Capaldi’s lyrics to footballers such as Chelsea defender Ben Chilwell talking freely about seeing a therapist following the injury that forced him to miss the World Cup in 2022 (The Sun called him “brave” for speaking out).

Of the roughly 108 people who took their own lives every week in England and Wales in 2022, 75 per cent of those were male. It’s a sobering statistic; one that hammers home the importance of talking about mental health. Sasha and Natthasiri, both 18 and also from Hackney, are best friends who spend most of their time BMXing with mates. Sasha admits that, a few years ago, he was “too young” to understand emotions like anxiety and depression. “Now that I’ve gotten older and I understand more about myself, I can say: ‘Oh, I have depression,’” he says. Natthasiri, who is sitting next to him, nods his head. “We’re always checking in with our friends,” he says. “With [Sasha], I just know him so well. I can tell immediately.” Sasha gives him a reassuring punch on the arm and they smile, before quickly laughing off the warm moment to avoid embarrassment. Later in the day, the pair start lining up their plans for the weekend. Key highlights on their agenda: BMXing and hanging out.

Fred wears jacket GUESS and top, hat and accessories talent’s own

Fabian wears jacket and shorts GR10K, shirt BIANCA SAUNDERS and tie TURNBULL & ASSER

Undeniably, a significant factor in the decline of young boys’ mental health is the sharp rise of far-right influencers, incel culture and toxic masculinity that lives in all corners of the internet. Andrew Tate, one of many figures in the MRA (men’s rights activism) sphere, is out-and-proud in his hatred of women. In fact, he admitted it casually on the podcast Anything Goes with James English in 2021: “I will state right now that I am absolutely sexist and I’m absolutely a misogynist.”

At the time of writing, Tate and his brother Tristan are in the midst of an ongoing investigation over rape and human trafficking claims, with prosecutors identifying several female victims. They were detained in Romania in March, before being released from custody under judicial controls, and are awaiting extradition to the UK to face further charges. Dates for their trials have not yet been set.

Both before and after these charges were levelled, Tate continued to amass a loyal fanbase of young men, with educators speaking openly to reporters about the fears they have of children being influenced by his “teachings”. As well as the blatant and violent misogyny he espouses, Tate lures in fans with promises of great wealth and success, often showing off online about his lifestyle of fast cars, luxury yachts and private jets. While his YouTube channel, where he’d regularly post videos on how to “get rich quick”, was taken down by the video platform in January, #AndrewTate video views on TikTok are well into their billions, despite the fact the posts come with a “be hate aware” warning.

“I don’t even think his fans believe [what he says] themselves,” Fred says. “I think it’s for the shock factor. And I think they like winding up ‘woke’ people.” Zane shares a similar thought. “Generally, it is toxic and I don’t associate with it. I think some people find him funny, but they never really take him seriously.” And yet, when it comes to young men, “the Tate effect” is one of the most talked-about issues of recent years. Research conducted earlier this year on 16 – 29-year-old men showed that one in four believed it was harder to be a man than it is to be a woman.

Miles wears top, jacket and skirt KNWLS

More surprisingly, boys and men from Gen Z are more likely than baby boomers – those born between 1946 and 1964 – to believe that feminism is doing more harm than good. Feminism, as in equality between the sexes. Is that so surprising? For hordes of disillusioned young men, Tate provides some sort of antidote to all their fears, paranoias and insecurities.

Parading as an omniscient, god-like figure with capitalism at his fingertips, he feeds off the right-wing media and its claims of masculinity being “under threat”. His bravado, wealth and hyper-masculinity is, for many, appealing – he’s a father figure guiding young men to their ultimate destination: success (financial, sexual and otherwise).

While the boys we speak to today aren’t watching Tate – or, at least, taking him seriously – they’ve all seen the impact of his viral misogyny play out in front of them, especially in school. “Teachers were always getting sexualised by boys in my year,” says Natthasiri. “Some of the [comments] were vile. And there was a day where they went around slapping girls’ arses because on TikTok it was saying it was ‘slap a girl’s arse day’.”

“There is a certain breed of straight man who thinks that everything is for the public and for their friends, and it’s definitely not,” says Fred, referring to explicit images of girls that have been shared around by boys in his school. “I’m not afraid to put people in their place – I’m quite outspoken if I need to be. I love peace and I hate arguing with people, but if I have to, I will.”

Currently, Cormac, Jack and Evan are choosing the A‑Level subjects they’ll be studying in sixth form: between them, they’ve picked triple science, art, geography, history, computer science and Spanish. When it comes to school subjects, certainly, they have options. But like most 16-year-olds, they’re concerned about the future.

“In a really privileged way, I worry about trivial things like GCSE grades and homework deadlines,” says Cormac, who is considering a career in politics or international relations. “I feel a bit detached from climate change – not in an apathetic way, but in a way that I don’t feel directly impacted by it, even though that’s kind of selfish.”

Jack, however, is on the opposite end of the spectrum. “Climate change really scares me,” says the 15-year-old. He’s passionate about biology and is considering it as a university subject. “It’s kind of crippling, because there’s not much you can actually do about it on a personal level. I often feel quite helpless about the issue.”

He talks about how climate change can be presented in the media – how it can often sound as though it’s down to us as individuals rather than the corporations spilling tankers of oil into the sea. “They make it seem like it’s your fault that the climate is changing. And even though I don’t think it’s really down to the individual, it still makes it feel very personal.”

As a trans man, Miles’ worries are very personal. Growing up in Portsmouth, he came out at school and suffered unrelenting bullying from his peers. “I’ve blocked a lot of it out of my mind,” he says. “School was pretty traumatising. I think it was brave of me, looking back on it. I’m surprised I could manage all of that. But I think it set me up for now. I know what I’m doing and I feel like I’m resilient.”

Now 19, he moved to London at 18 to study hair, makeup and prosthetics at London College of Fashion. But he’s planning on leaving soon due to a difficult staff member. “My lecturer is quite sour about the fact that I do drag and he lets that reflect in my grades,” he says, “so I’ll be branching off into something else.”

He’s also worried about the future of trans healthcare in the UK and the sharp increase in transphobic attacks, both on and offline, in recent years. Last year, hate crimes against trans people hit a record high in England and Wales, with an 11 per cent increase in recorded incidents compared with 2022.

Meanwhile, on social media, there is an everyday battle raging, thanks to transphobic posters arguing against the human rights of trans people. “It feels like I’m constantly defending myself and my community. I feel like I’m always on the defensive,” Miles says. “Sometimes I just want to curl up in a ball and not go outside and not talk to anyone, because it’s easier than having to face the world.”

Odie wears top BIANCA SAUNDERS

Zane wears jacket C.P. COMPANY, shirt and tie VALENTINO and trousers GUCCI

Such aggressions aren’t, of course, confined to social media. Young people feel let down by out-of-touch politicians governing their futures. That’s nothing new – youth have long rebelled against the people in power making choices that directly affect them.

But even with a new dawn promised by the recently elected Labour government, real change – and real undoing of 14 years of Conservative misrule – will take some time to be implemented. And for teenagers, that change needs to happen on multiple sides. Average rents rose by nine per cent in 2023, the highest annual increase since 2015. The average house price hit a record high of £375,000 earlier this year.

Youth services were cut by 77 per cent in the past decade. The money for 16 – 19-year-olds’ education was cut by 15 per cent. Britain’s nightlife is in a shambles, with pubs and nightclubs closing at alarming rates, mostly due to increased costs in everything from rents and bills to import fees via Brexit. And the cost-of-living crisis continues to damage Brits of all ages.

“There needs to be some implementation of a [political] system or a way of interacting with the public, especially young people, where it doesn’t feel so much like we’re just left to our own devices,” says Odie, who is 19 and from Bromley, southeast London. He’s passionate about nature and animal rights and hopes to work in this field, whether as a career or through volunteering. “There also needs to be more ways for people to get therapy. I don’t think there’s ever been real compassion or consideration for people’s interests, which makes sense, given our [last] government.”

Gen Z is, by many accounts, a politically engaged generation. But Zane disagrees. He sees his peers as being disillusioned by politics. “Young people are always overlooked by the government,” he says. “It’s probably why people my age aren’t really interested in the elections or anything that is happening.”

Fabian, at 13, and very much Gen Alpha, reckons he’s got a solution for youth disengagement: get more young people in government. “I don’t mean 13-year olds! But maybe a 25-year-old? There’s not much representation of younger people, which I don’t think is right. When they don’t get represented, people get upset.”

But it’s this youngest member of our street-real focus group who, perhaps unsurprisingly, is most fired up about the future. “[I want to be] out of the ordinary,” he says. “There’s nothing wrong with being ordinary. But I ask my friends: ‘What do you want to do when you’re older?’ They say: ‘Have a job, a house, have kids.’ I feel like I have to become something remarkable. I have to do something worthwhile.”

There’s no denying it’s a particularly hard world for young people now, all the concerns of even a decade ago magnified, warped and woven into the entirety of their lives, on- and offline. But among the rife misogyny and toxic masculinity we’re seeing played out daily, these boys represent something hopeful: that there’s a cohort of soon to-be young men who are checking in with their mates. Calling out bad behaviour. Switched on to the failings of politicians. Who are caring and confident and respectful of women.

Yes, there are currents of anger, apathy and disappointment within young people right now. But there’s optimism, ambition and determination, too. And by 2030, only six years from now, Gen Z will make up a quarter of the electorate, their enlightened numbers bolstered by Gen Alphas such as Fabian coming up right behind.

We’re calling it now: the kids are alright.

CREDITS

CASTING DIRECTIOR Lisa Dymph Megens TALENT Aaron, Abdulai, Brian, Cormac, Eben, Fabian, Fred, J, Jack, Jahari, Jerome, Josh, Korie, Miles, Natthasiri, Odie, Sasha and Zane PRODUCER Katherine Bampton PHOTOGRAPHER’S ASSISTANT Frankie Spence STYLIST’S ASSISTANTS Kit Rimmer and Elliot Bulman