Reclaiming Reykjavik: Iceland’s politically-minded youth are shaking up the music scene

Andrés' home

With a “Do It Together” motto and ideology inspired by anarcho-punk, the Post-Dreifing community are taking over Reykjavik.

Music

Words: Joe Zadeh

Photography: Steinn Thorkelsson

The nazis are in town. That’s the topic of conversation on this grey afternoon in Reykjavik. I’m sat in a top floor apartment listening in on a meeting between five young artists. Washed crisp packets drain in the kitchen sink (recycling apparently), and the dining table is covered in Bali Shag tobacco and Oreos. On the window sill there is a plant potted in an old can of chopped tomatoes sitting next to a DJ mixer.

Andrés – the owner of the flat, known for producing both ambient and ecstatic electronica as Hot Sauce Committee and one half of We Are Not Romantic – is making coffee in a pan. The others sit on the balcony smoking rollies, passing around a Pot Noodle and snapping biscuits in half. It’s cold. Andrés hands out the mugs – which include a Star Wars mug, a Harry Potter mug, and a mug with a “MAN BRAIN” illustration in which one side of the brain is labelled “tits” and the other “beer” – and pours the steaming coffee straight from the pan.

Earlier today, a group of 10 – 15 neo-nazis marched through Reykjavik, waving their flags and handing out flyers, flanked all the way by police. When a passerby ripped up a flyer, they were branded a “race traitor”. Among the group was Simon Lindberg, chairman of the Nordic Resistance Movement, a neo-nazi organisation with groups in Sweden, Norway, Denmark and now Iceland. NRM were linked to bomb attacks in Gothenburg in 2017.

“They were being very vocal about their agenda against immigrants and refugees,” says Bjarni, a 23-year-old songwriter (now in Supersport but formerly of the breakthrough indie band Baghdad Brothers). He has a clipped fringe and a modernist sense of style, dressed in a black polar neck and brown check trousers. Everyone murmurs. He turns to me, “We want to counter them by throwing an outdoor punk show on Saturday, in the exact same place they protested.”

These five are part of post-dreifing (pronounced “post-drey-ving”): a thriving Reykjavik art collective that’s 30+ artists strong and growing. They have no specific genre or aesthetic: members include indie bands, riot grrrl punks, synth-pop songwriters, thrash rockers, hardcore heads, ambient wizards, and techno nuts. Instead, they are all united beneath a core set of principles that are rooted in anarchism: self-sufficiency, community, and collaboration.

Iceland has a history for this kind of thing. You could say the entire alternative music scene here was born from the anarcho-punk wave of the 1980s, which had links to UK bands like Crass and peaked when a heavily pregnant 20-year-old Björk performed live on TV as the singer in KUKL.

What separates post-dreifing from most art collectives is their ages, which range from as young as 15-years-old to the still spritely age of 26. This intergenerational collective of teens and young adults have a pretty simple dream: create as much as possible for as little money as possible, and have plenty of fun doing it. (For a sample of their vibe, watch the video for Nokia Calling by We Are Not Romantic, a pounding rave song in which the singers are barely holding in their laughter.)

Post-dreifing don’t ascribe to the music industry’s core principle of what’s good is what sells. They don’t care if it sells. And they rarely charge for tickets or music, preferring a pay-what-you-want model. Perhaps it’s naive and idealistic to think this is sustainable, but for two years now it has worked, and it is only growing.

Reykjavik music venue, R6103

Iceland’s leading music critic Arnar Eggert described them as “a breath of fresh air” while eating eat soup in the canteen at the University of Iceland, where he lectures in Popular Culture. “We used to get great individual bands here and there, but we haven’t had a strong collective like this for a very long time,” he says. “A lot of young musicians here get stuck in the trap of writing into a mould of what they think the world expects of Icelandic bands, and what will do well internationally. These post-dreifing guys are rebelling against that.” This year, the new energy in Iceland’s scene will be reflected at the country’s major festival, Iceland Airwaves, where organisers have focussed less on international headliners and more on the booming talent at home.

Post-dreifing acts rarely sing about political issues, but they appear to be an inherently political group. “I might write sad love songs,” says Bjarni, “but if I go and play these songs at Austurvöllur (parliament square) to protest the way refugees are being treated in Iceland, then it is political music.”

He’s referring to an event earlier this year when a group of refugees residing in an isolated camp in Iceland decided to protest outside parliament in a push for the right to work, health care, and to have their cases for asylum fully examined by authorities. Numerous post-dreifing artists turned out in support.

“I was there,” says Örlygur, a member of the bands sideproject and Korter í flog – everyone is in at least two bands. “We were just playing drums, not even protesting or yelling, just talking and making cardboard signs.”

“Then the police attacked the group very violently, kicked a lot of people, and used pepper spray for the first time in Iceland since the financial crisis of 2008 – which was the biggest protest in the history of our country,” says Bjarni. “It is the most serious case of police brutality that we’ve witnessed in Iceland probably ever.”

“After this,” says Örlygur, “people were just pissed. We decided we’re going to do everything we can to get these refugees their demands.”

“Later that month,” says Bjarni, “we heard that a group of nationalists and racists were planning a protest against the refugees in Austurvöllur. So we threw a huge concert at the same place and time to ridicule them. We told everyone who came: don’t interfere with these people, just enjoy the concert. We got the biggest rap duo in Iceland to play, Jói Pe and Króli, and for five hours we had a great time. There were hundreds and hundreds of people there.”

Did the far right turn up?

“Yeah, they came. They did nothing. They were just old. You kind of just felt sorry for them. People blocked them off with gay pride flags, so you couldn’t even see them.”

Every one of my conversations with a member of post-dreifing either starts or ends with the line: “I’m just an individual, my views don’t represent the collective as a whole”, and they are quick to remind me that not all of their members were involved in these actions. This is part of their core ethos: they are leaderless, or, to say it cleverly, nonhierarchical. Every decision is agreed upon in meetings and work groups which anyone can attend. “It can be complicated having so many people involved,” Andrés admits.

Today’s meeting isn’t about neo-nazis, that was just while the coffee brewed. It’s about a forthcoming compilation that they will release to showcase grassroots artists in Iceland. They call their compilations DRULLUMALL (which translates as “mud cake”, like a kid would make) and they’ve done two so far. Andrés is chairing this meeting. He’s sat on the floor wearing square framed glasses, a USB cable hanging around his neck, playing songs off his laptop that have been submitted for consideration. Behind him, the window looks out onto the distant green mountains of Reykjanesfólkvangur.

Andrés puts on a frenetic bubblegum pop song, followed by a 10 minute ambient track. “How long is the compilation going to be?” says Bjarni. “Quite long,” says Andrés, before pressing play on an extreme noise song that makes me flinch. They all nod approvingly. “Very promising,” says Bjarni. Everyone gets excited when Andrés plays a song by a 60-year-old man he’s found in Northern Iceland, “a true outsider artist” who makes surreal and unconventional rock music in his garage. “His stuff is amazing,” says Andrés, “but he doesn’t like our logo… Oh, and he wants the title of the compilation changed.”

I leave the meeting and go for a walk around the centre of Reykjavik with Örlygur and Joi. Joi (known by the artist name Skoffin) has a shaved head and is wearing a denim Coors Light jacket. He has an intelligent way of talking, and I’ll later find out he did his BA thesis on anarchist movements. Örlygur is wearing a military jacket, has a shaved blonde undercut and looks a bit like a Nordic Christian Slater circa True Romance.

“This was the place to be,” says Joi, rubbing on the dusty window of a permanently closed music venue called Húrra. We peer at the builders inside. “It was easy to get gigs here and it had the best backline in town. They booked real alternative music. But then it got bought off and now they are turning it into a sports bar. The concentration of sports bars in this area is already so high. I mean, look,” he says pointing at the building next door – it is a sports bar.

Húrra was just one of many much-loved music venues here that have been shut down and turned into tourist related business, including Faktory and NASA. Reykjavik’s music scene has become victim to the same trends that threaten independent music scenes in London, New York and most other capital cities around the world – it just feels like it’s on steroids here because the city is so small.

Many of the venues that do stay are becoming more and more engineered towards the passing tourist or wine drinking 30-something with disposable income, rather than the local youth. And with the legal drinking age in Iceland set at 20, most young people had simply run out of places to be.

So they made their own scene. What started as a melding of friendship groups at an all ages show in 2017 has now evolved into a city-wide youth movement. They put on gigs on a weekly basis, release albums on a monthly basis, and even organised their own festival over the summer.

When I ask where their money comes from, Bjarni says, “We’ve never really have any.” Instead, they seem to achieve things using their guiding philosophy of “DIT” (do it together). Take their festival, for example, which was held in the abandoned elementary school in a small hamlet in the North West of Iceland called Borðeyri (population: 16). They booked 32 bands who were willing to play for free or travel expenses, borrowed music equipment, built stages, went dumpster diving for food to make vegan stews, and got leftover bread and pastries from bakeries. Everything else was donated. Attendees were told to bring their alcohol and camping equipment. Three elderly women from Borðeyri came and had a lovely time.

“It survived on volunteers,” says Örlygur. “We worked all day at the festival, from 9am-4am, then went to bed, then got up at 9am to start again, and then we’d also play two or three shows each.” They sold over 300 tickets at a very cheap 3000ISK (£25), and used the money to buy rice, and to pay the venue and the police. “We had to pay the fucking cops to be on shift! They came for half an hour on Friday and everyone just felt a little more unsafe while they were there.”

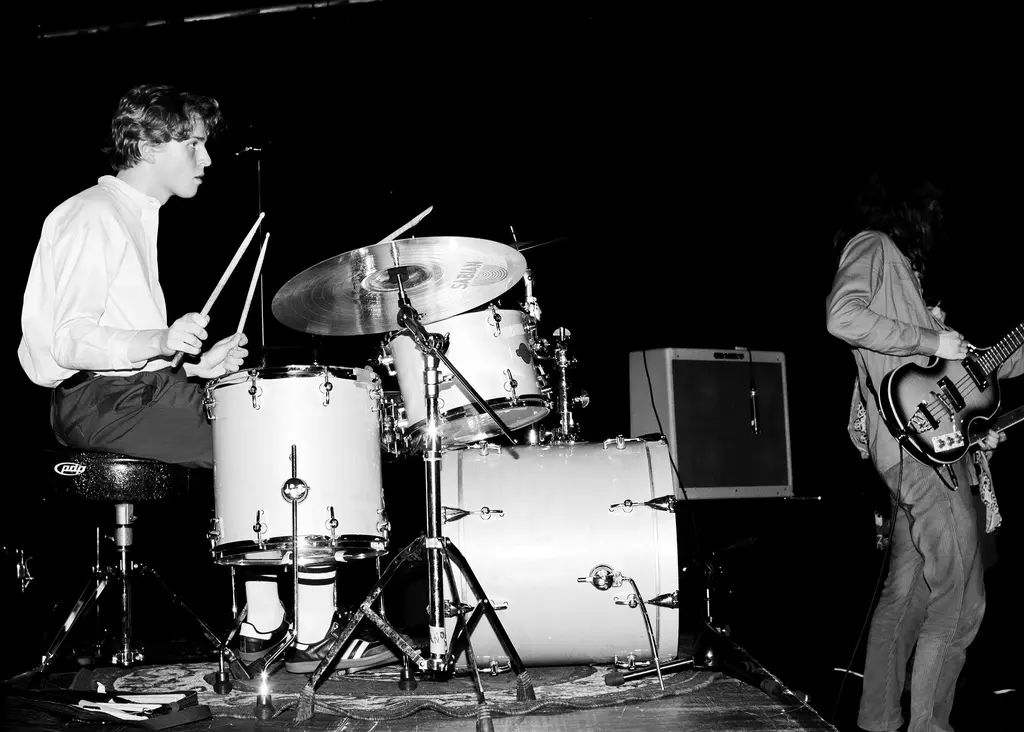

Iðnó Side Project Hjálmar, Örlygur and Atli

Iðnó Stirnir Kormákur

Iðnó Gróa Karólína and Fríða

Iðnó Gróa

Iðnó Ólafur Kram Hildur and Eydiís

“Post-dreifing are like a wave,” says Ægir Sindri Bjarnason, “they are bringing life to the scene in this small city.” Bjarnason runs the best small music venue in Reykjavik: R6013. But you won’t find it on Google Maps, you need the exact address, because it isn’t really a music venue – it’s Bjarnason’s house, and another example of the DIY ethos that’s spreading through this city’s younger generation.

Two years ago, triggered by “the need for a different space for shows, that’s not the same two bars that we’ve been playing for the last six years”, Bjarnason decided to clear out his basement and turn it into something. At first it was just a rehearsal space, but it gradually turned into a venue. He’s put on over 90 shows (every one of them for all ages) in this long room beneath his living room and kitchen, cramming in a maximum of 80 people to see everything from hardcore punk to post-dreifing artists. Last year, the location was incorporated into the Iceland Airwaves programme alongside other small venues throughout the downtown area, and it will likely play an “off-venue” role at this year’s festival.

Inside, the venue is, well, a basement. The walls are lined with scruffy drawings and set lists, old sofas sit at the back and there’s a single mattress on the floor. 26-year-old Bjarnason describes himself as a “hardcore punk and grindcore” kinda guy, yet he is one of the calmest people in Reykjavik. He has shaggy hair and speaks in a gentle and thoughtful way. As we chat in his kitchen I notice toys on the floor. He has a five-year-old daughter, but she doesn’t mind the noise and can easily sleep through a grindcore band playing in the basement, he says.

Lately though, she wants to be at the shows with her dad. Come to R6013 on an evening and you’ll find Bjarnason sat at the entrance with his daughter on his knee, managing the sound desk while simultaneously checking people in through the door.

Earlier this year, he set up a Patreon centred around this space and the small record label he runs. It blew up. Within two days, donations had pushed him to his minimum goal. He quit his job and has since worked on R6013 full time. “I’m very grateful for it,” he says, “but I feel weird about taking people’s money. I have this constant rationalising conversation with myself about this. I have to repeatedly tell myself I’ve earned it. I hope I have.”

R6013

Iron Lung at R6013

It’s Saturday, and it’s pissing it down. Bjarni’s dream of an outdoor punk performance has been called off for safety reasons, but that hasn’t stopped numerous members of post-dreifing from lending their hands and expertise to the anti-nazism protest in the town square.

Around 200 – 300 Icelanders have gathered in the crappy weather to hear the protest speakers, which include representatives from Amnesty International, Reykjavik city council and No Borders (who helped arrange it). All of the equipment is being ferried around on a cart with “R6013” written on the side. The only nazi I see knocking around today is the written word, on a sign that says “NAZIS EAT SHIT AND DIE”.

Mirrored by the rise of Greta Thunberg and the school strikes, there’s been a growing fantasy among disillusioned and nihilistic millennials, like myself, that while we wallow in debt and mourn our losses, Generation Z are going to be a radically productive and progressive generation who will rescue the world and put things back to normal. When you’re around the post-dreifing crew, it’s hard not to get a little carried away on these ridiculous notions.

The protest ends and the group dash three blocks over to Iðnó, an independent venue in an old theatre by the lake. By 9pm, people are streaming into the venue, and it’s safe to say that I, a 31-year-old, am the oldest person here by a long stretch. There are boys in Puffa jackets and long leather dusters, and girls in abstract mini-bunned hair styles with big hoop earrings. The music starts and I feel like I’m in a school disco scene in a Larry Clark movie. I see Joi at the bar; he’s wearing a gold panel belt that says “ICELAND”.

Two boys who can’t be older than 17-years-old, and go by the name Tucker Carlsson’s Jonestown Massacre, begin playing a hypnotic set of experimental drone on guitars that for some reason makes me feel very emotional. At one point, they take their shoes off and sit down. And then everyone in the crowd sits on the floor too. Some lie and close their eyes. Paralysed by indecision, I stay standing and it feels like I’m in a strange lucid dream. Next a four piece called Stirnir wander timidly onstage and deliver a moody and evocative set of haunted guitar pop. Bjarni comes over and puts his hand on my shoulder, “Everyone in this band is 15 or 16 years old!” he grins, then wanders back down front to Örlygur and Joi, who all look on like proud dads.

It reminds me of something Bjarni told me in a cafe earlier. When they finally finished the festival during the summer, he and Joi zoomed back to Reykjavik, exhausted, to put on a show in R6013 for Norwegian bands they’d brought over for the festival. The basement was at capacity, so they went outside and collapsed onto a sofa in the backyard. “Joi turned to me,” says Bjarni, “and he said, ‘You know what: the most important thing about all this is the community we’ve made. It’s not the concerts or music, it’s the community. This is what people are going to remember.’”

Iceland Airwaves takes place 6 – 9 November in Reykavík. Travel was provided for this article by festival Founding Sponsor Icelandair. Travel packages can be found here.