Millbank to Owens Park: how the student protests of 2010 informed the politics of now

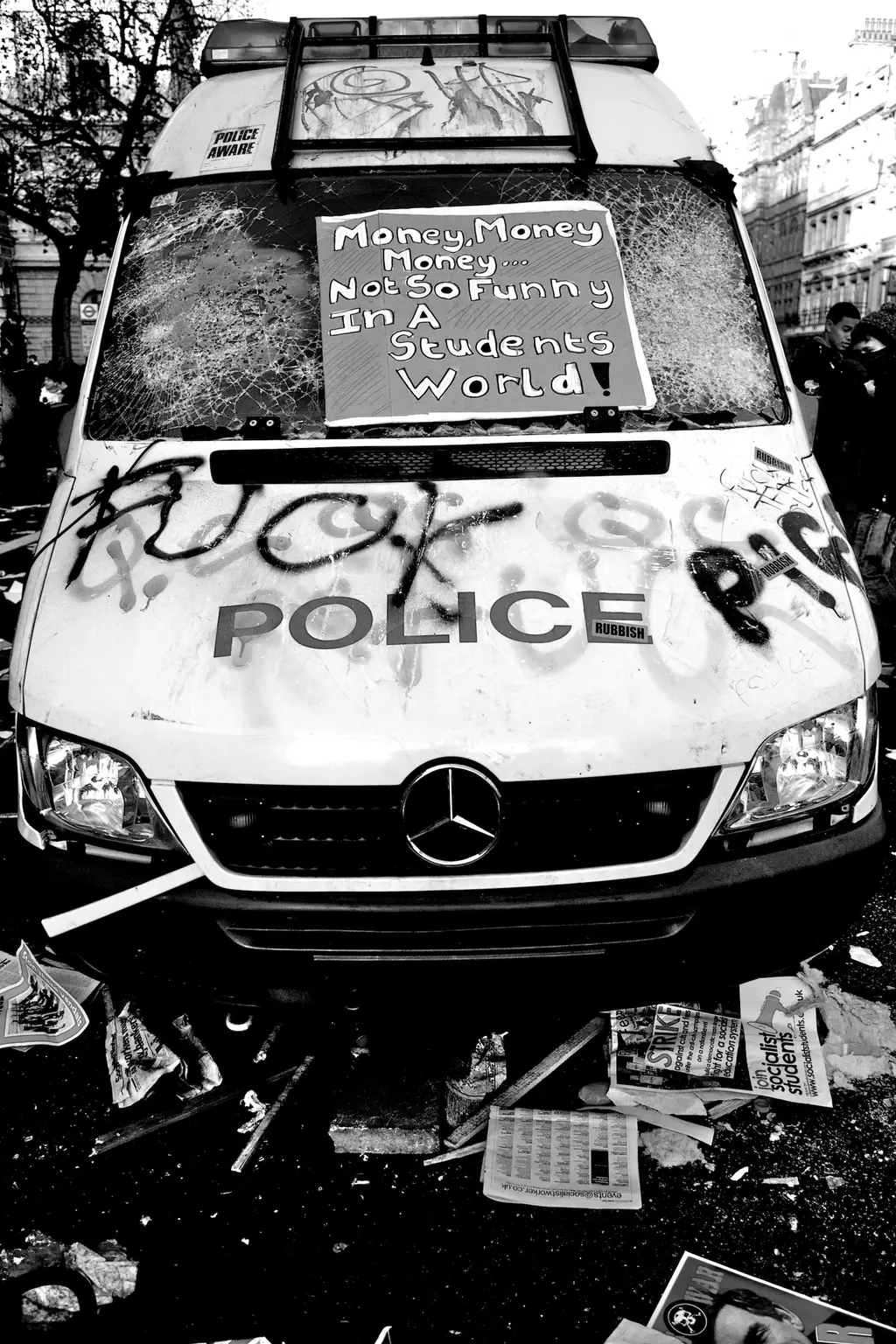

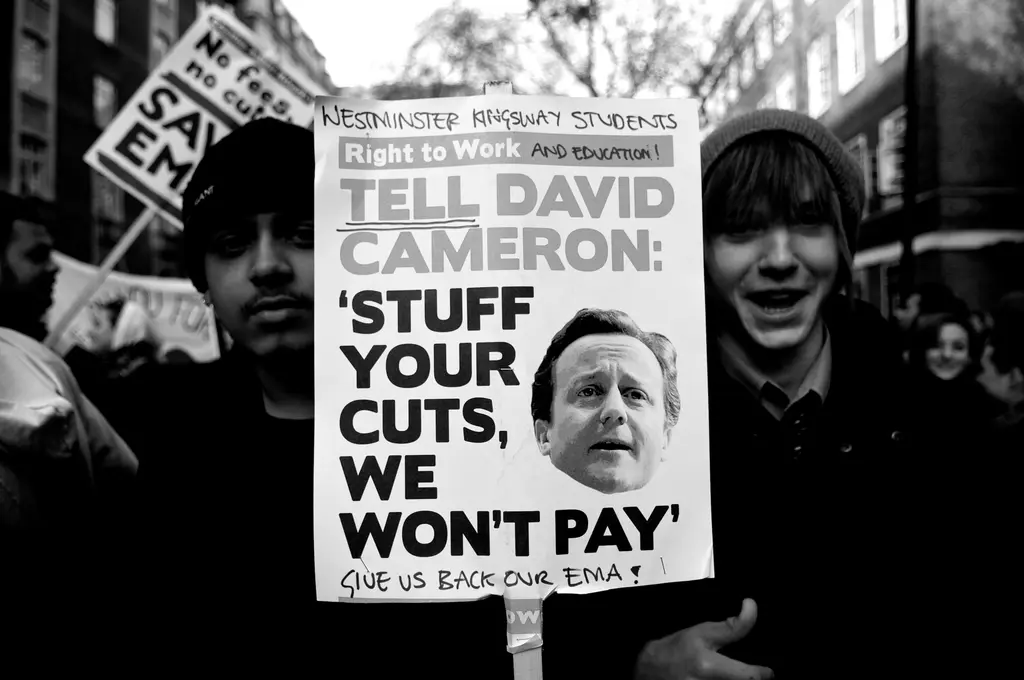

As students occupy an unused building at the University of Manchester, we speak to photographer Marc Vallée who finds precedent in the Millbank Tower protests a decade ago.

Society

Words: Amy Francombe

Photography: Marc Vallée

On 12th November, 15 undergraduates occupied Owens Park Tower, an unused residential building on the University of Manchester campus.

Duped into taking sub-par online lectures, and forced to quarantine in box rooms, the students were protesting rents: ones that Sarah Cundy, a history student at the university and vice-chair of Manchester Momentum, claims 74 per cent are currently unable to meet due to loss of work.

Exacerbated by flooding, which forced 100 freshers to sleep on the floor in a communal area, and an £11,000 security guarded-fence around the university’s Fallowfield campus (since pulled down) – the students began to retaliate.

When a protest planned for 10th November was cancelled due to the threat of fines, members from UoM Rent Strike and 9K 4 What – organisations demanding better treatment of students and staff – snuck into Owens Park Tower, barricaded the doors with sofas, and hung a “Students Before Profit” sign out the 10th floor window.

Eleven days later, the protestors are still there, stating they will not move until University of Manchester’s Vice Chancellor Nancy Rothwell meets with them to discuss a 40 per cent rent reduction, a no-penalty early release clause from their tenancy contracts and an increase in support for students in halls of residence.

For Marc Vallée, the photographer behind book, Millbank and that Van, the situation is nothing new.

“The way students are being treated, particularly under the pandemic, is demonstrative of what the students were fighting against 10 years ago.”

In a twisted turn of history contorting itself, the Manchester sit-in came exactly 10 years and one day after the legendary Millbank Tower occupation, when 52,000 angry students and schoolchildren smashed through the Conservative Party headquarters in Westminster to protest against the trebling of tuition fees.

“On the one hand they were fighting against the raise in fees, but ultimately they were fighting against the whole change in the culture of education,” Vallée says.

At the turn of the decade, England’s higher education underwent deep structural changes to how it was financed. Five months after the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition was installed, the government unveiled an extensive package of reform which allowed universities to increase the cap on tuition fees to £9,000 per year, slashing government funding from 50 per cent to 25 per cent as a result. The move was seen as a knife in the back for young people who had rallied around then-Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg and his pre-election pledge not to raise said cap.

“It was a result of 30 years of neoliberalism and Chicago Boys economics [a school of thought that promoted the virtues of free-market principles in society],” Vallée continues. “The increase in tuition fees accelerated the growth of marketisation in higher education and radically reshaped the students’ relationships with their universities. It turned the joy of learning into something you obtain and pay for, which subverts it and makes it less.”

Fast forward 10 years and the system is in crisis. Overly reliant on student fees, and in dire need of funds following a 16 per cent drop in domestic enrolment that has left almost three-quarters of universities in “a critical financial position”, universities are treating students like consumers whose money matters more than their education – reluctant to abandon “the student experience” until they’d collected their cheques.

It’s why Vicky Blake, president of the Universities and Colleges Union suggested in The Guardian last month that universities waited to move teaching online until after the fee rebate deadline passed. For Vallée, the whole thing is a “capitalist Catch 22”.

“Universities are responsible for the safety of their students, but without their fees, they’ll collapse,” he says. “The government needs to step in like it has for so many other sectors, or better yet, the whole system needs to be restructured so that universities aren’t reliant on fees, which will mean students are no longer viewed as commodities.”

The 2010 student movement shook the government, police and much of the media. The spontaneous radicalism and willingness to fight gave rise to a more political generation and, although the tuition increases went ahead, the spirit of direct action became increasingly normalised. “Millbank was about collective power,” Vallée agrees.

It’s an energy that the Class of Covid-19 is tapping into now. “The anger from students today resonates with what I saw ten years ago,” Vallée continues. “Once again they’re being sold empty promises, and I implore them to look back to Millbank Tower and remember the power of collective action. It’s time to remind those at the top who our education system is meant to serve.”