Francesca Sorrenti on the rise and demise of heroin chic

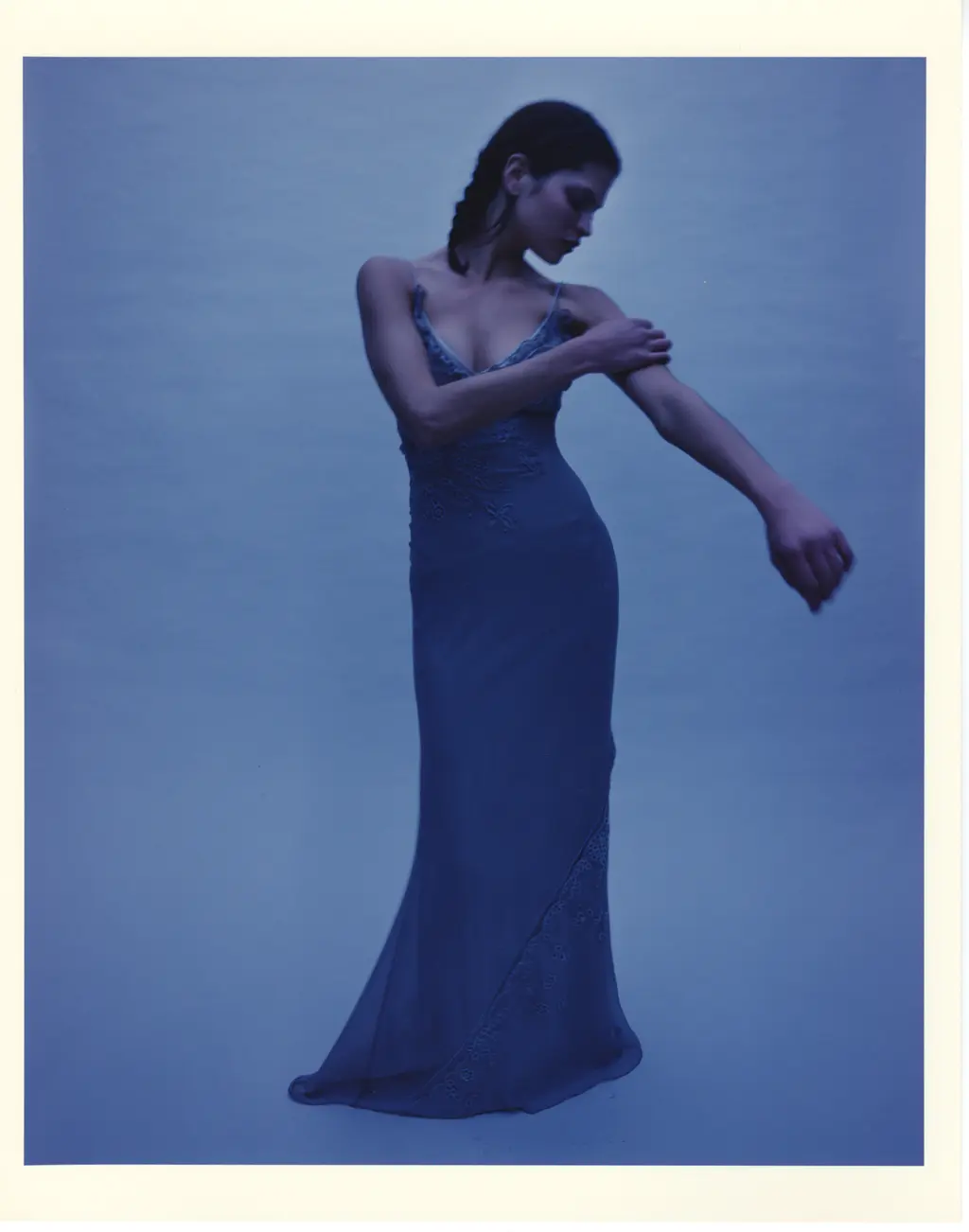

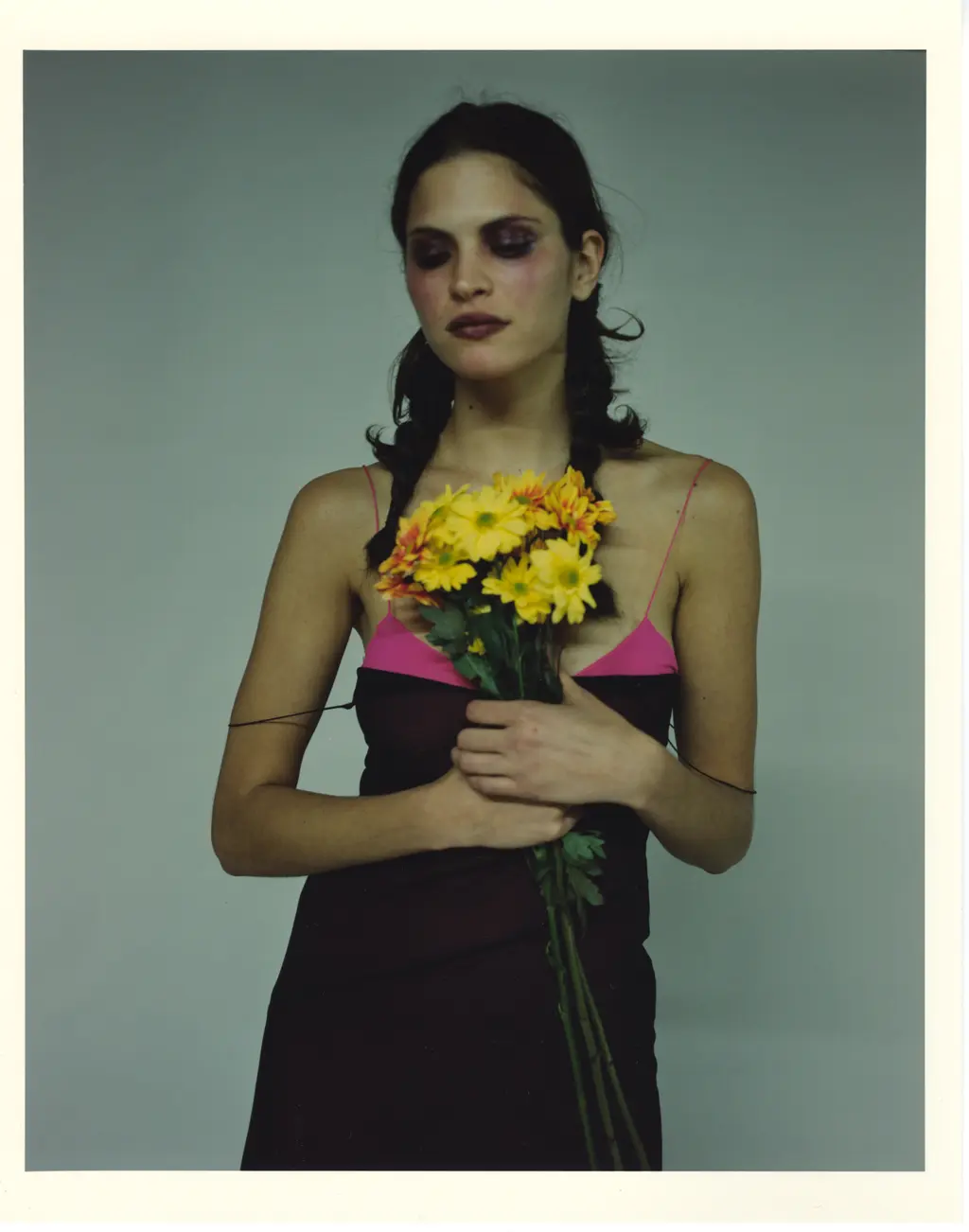

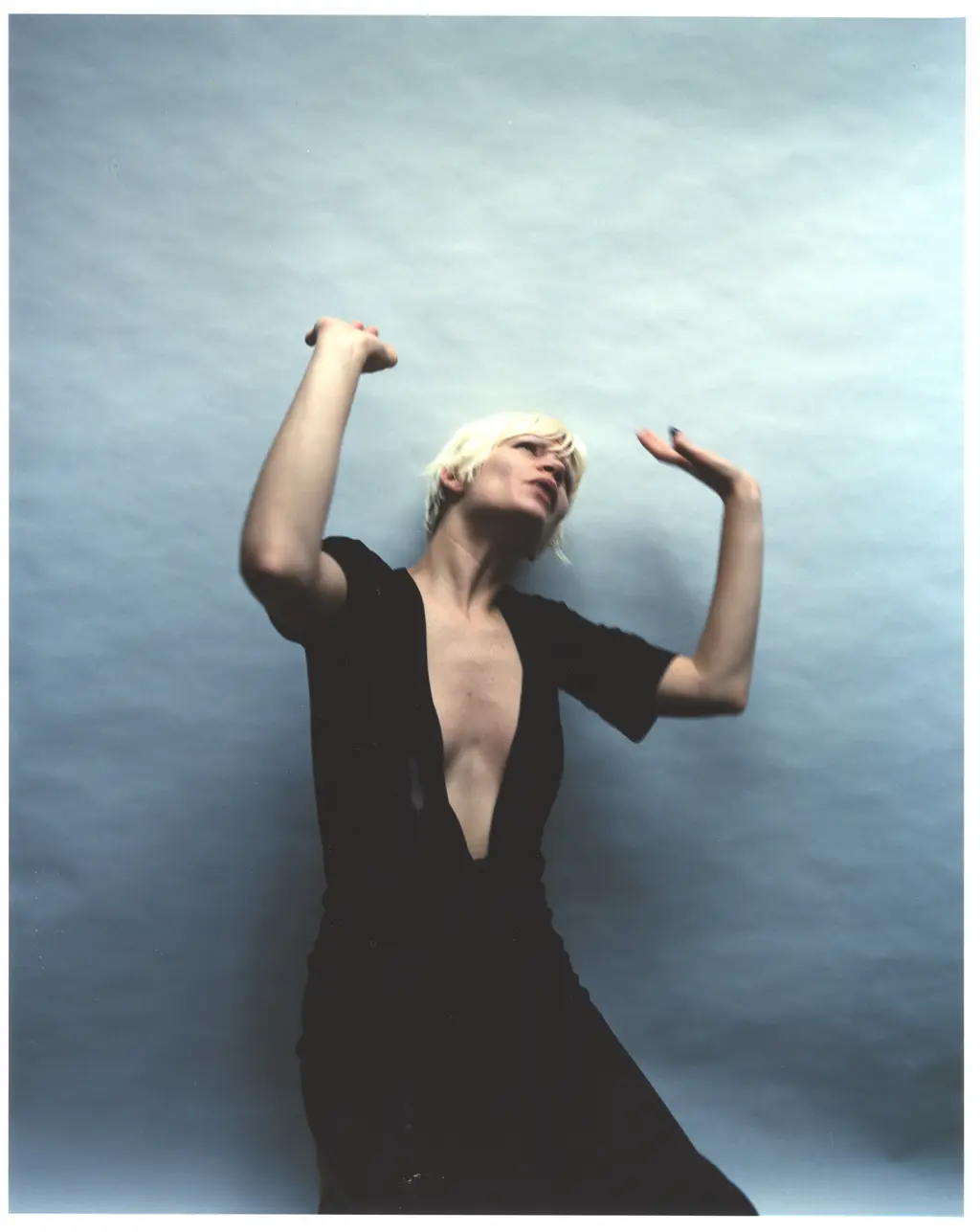

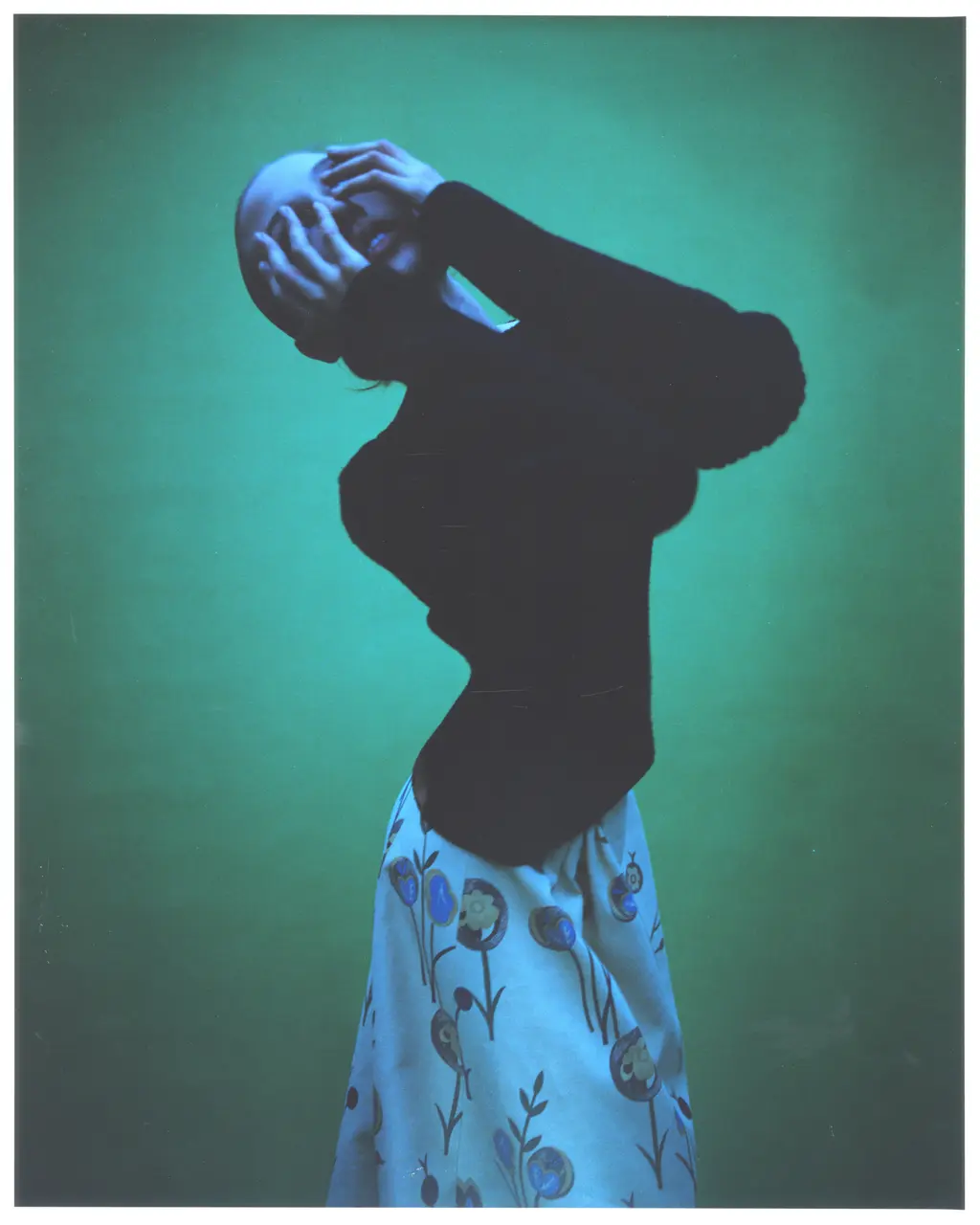

Davide Sorrenti’s girlfriend at the time, Jaime King, became the poster girl for the heroin chic movement. All images courtesy of the Davide Sorrenti archive.

The end of heroin chic’s popularity coincided with the shocking death of photographer Davide Sorrenti. A new documentary celebrates his life and work and questions why he was intrinsically tied to the movement.

In one of the most recognisable images by the late photographer Davide Sorrenti of his girlfriend Jaime King, she is sprawled across a sofa, cigarette smouldering, hands pulling at her ripped tights. The spaghetti straps of her top frame her emaciated figure. Her clavicles and gangly arms appear shockingly thin. It wasn’t an outtake from an intimate night at home – though that is where much of the pair’s imagemaking occurred – but a photo that was actually published in a mid-90s issue of the fashion magazine Detour. It spat in the eye of the conventional female beauty du jour – the busty glamazon supermodels on every billboard and in every magazine spread.

By this point, the “3rd summer of love” – promised by The Face in a strapline accompanying Corrine Day’s iconic 1993 cover of a teenage Kate Moss on the beach – had firmly arrived. And it wasn’t a warm and welcoming summer, either; it was instead marked by the nihilism of the grunge movement’s insidious creep into mainstream culture, largely via the music of Nirvana and films like The Basketball Diaries and Larry Clark’s Kids. But just as quickly as the trend ignited the creative fires of some of the fashion industry’s biggest names (Marc Jacobs’ collection for Perry Ellis, for one), it was snuffed out. In hindsight, it’s clear that much of the reason for grunge’s rapid demise was the movement’s destructive bedfellow: heroin chic.

Even if it’s in the tabloid media’s nature to always pin the blame on a specific culprit, identifying the genesis of heroin chic in the fashion world is near impossible. And those who were furthering its aesthetic merits largely didn’t mean to. Leonardo DiCaprio told Detour in 1996 that he made The Basketball Diaries to “help make some kind of statement against heroin.” On the contrary, it only helped to glamourise the trend.

A new documentary by first-time director Charles Curran, See Know Evil, remembers the life and work of Davide Sorrenti – brother of Mario, boyfriend of Jaime, and dear friend to many of the names who have now come to define ’90s counterculture – and attempts to dispel some of the myths surrounding the movement, in particular that Davide’s death at the age of 20 was in some way its inevitable, tragic conclusion.

“Davide’s death was painted in the media as the result of a heroin overdose,” explains Francesca Sorrenti, Davide’s mother and a close collaborator with Curran on the documentary. “There wasn’t enough heroin in his system to kill a fly.” In truth, the cause of death was never conclusively determined, but the likeliest cause was that Sorrenti had fallen behind on his fortnightly blood transfusions, a necessity given his genetic blood disorder, thalassemia.

“Davide’s death was painted in the media as the result of a heroin overdose. There wasn’t enough heroin in his system to kill a fly” – Francesca Sorrenti

Once this myth is cleared up, it’s obvious that the misinterpretation of Sorrenti’s work – as a gonzo-style trip through the seamier corners of ‘90s youth culture – perhaps says more about the censorious attitude of the tabloid media than the young photographer’s circle of friends. “These movements always start somewhere, and it’s usually in the media,” continues Francesca. “You watch the news and it’s all about laying the blame on an individual, about pointing the finger. They’re always the first to condemn what they created.”

That isn’t to say that there wasn’t a darker truth to what the media was printing. “What happened in the ‘90s with the fashion industry is that nobody took control [of the drug problem],” she adds, speaking from the perspective of having been a fashion photographer herself. “But it was across the board: it wasn’t just one entity, the designers or the modelling agencies specifically.”

“Amy Spindler, [a style editor] from the New York Times was a friend of mine,” Francesca continues. “I remember she came to my apartment to say that [drug use was] getting out of hand. You would go to a fashion show, and there were models nodding out. I was on a photoshoot in LA, and this girl came who said she was on sleeping pills because she took a flight, but she was on heroin. I called her agency and told them I wouldn’t shoot her; I wanted her mother to come here and pick her up. You heard stories about fashion editors holding up girls against the wall in order to shoot. Kids would be calling up their agents to get coke. All of a sudden, it was one big party, and I was against it. Little did I know I was going to be the victim…”

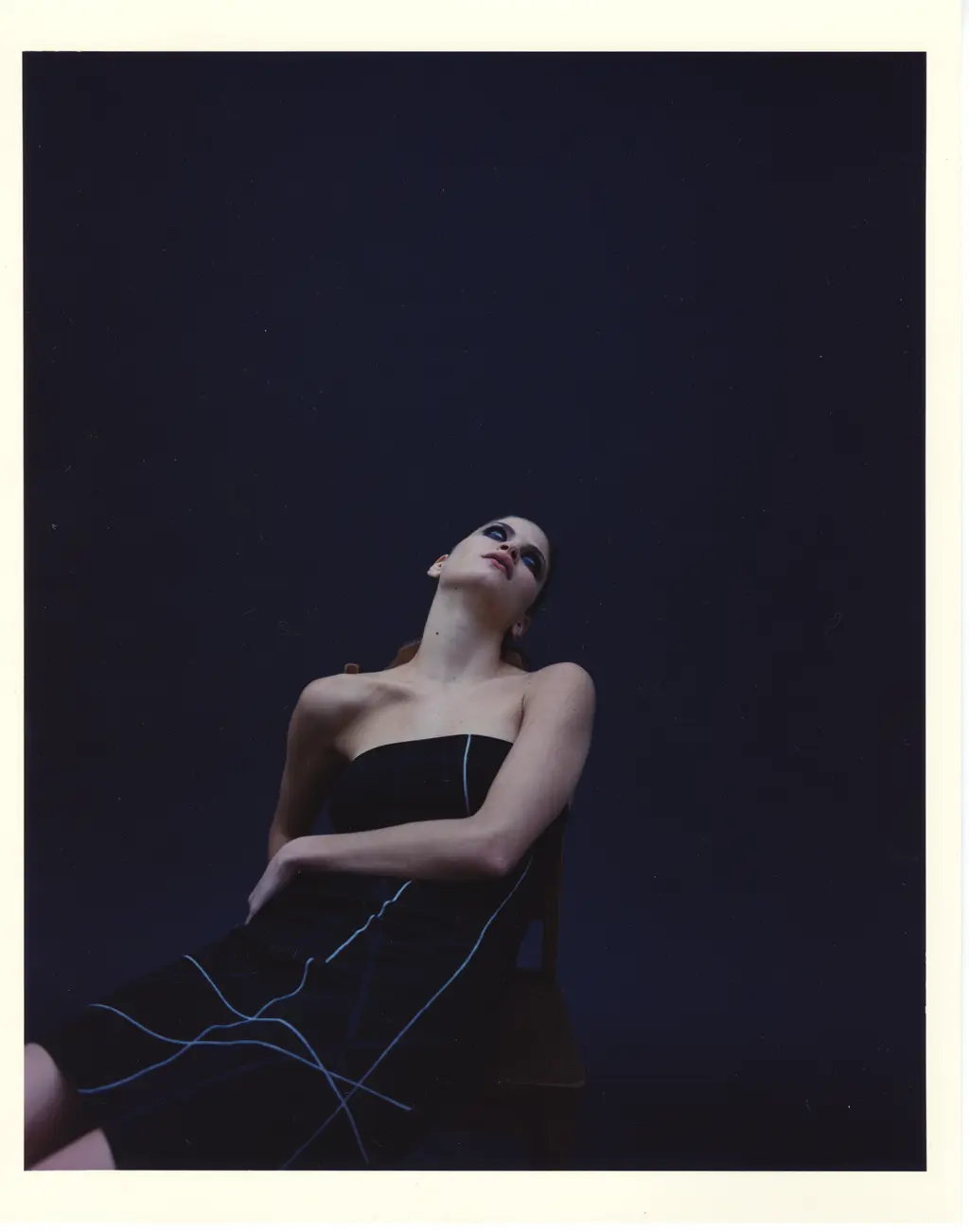

Francesca Sorrenti.

Even if Davide became the poster boy for heroin chic, the pain that colours his work was the product of his lifelong illness, not addiction. “If you look at his photography, it’s not about drugs; it’s about him creating this kind of dream world,” says Francesca. “He would tell me that it was as much about his suffering as it was his dreams. If you look at the bodies in his pictures, they’re always moving – it’s very trance-like.”

It’s true: just look at the many portraits Davide took of his girlfriend Jaime King, the model-turned-actress who was heavily associated with the movement, but recovered from her heroin addiction and has now remained clean for over 20 years. While one infamous photograph depicting King possibly preparing to shoot up has remained controversial, the bulk are just images of two runaway kids living the fast life in downtown Manhattan – a woozy, exhilarating testament to the all-consuming rapture of young love.

It’s the timelessness of these intimate portraits of love and friendship that has prompted a resurgence of interest in Davide’s work – particularly thanks to social media platforms, where the once-near-forgotten photographer’s work has inspired a new generation of young artists, including Charlie Curran, the director, who was just 20 when he began work on the seven-year project. “We’re going through a ’90s moment right now,” says Francesca, “but I was amazed to see the kids at the screenings who had found Davide’s work over the internet. I had a young girl come up to me and say, ‘I’ve been a fan of Davide’s work since I was young.’ I said, ‘How old are you?’ She was 25!”

It was partly thanks to this mounting interest that Francesca finally felt ready to reintroduce Davide’s work to the world. “It took me a long time to feel ready to do something like this,” she explains, “because at the beginning, every time I looked at his pictures, it just became too much for me, psychologically. I would maybe spend a week afterwards feeling moody and not wanting to get out of bed, but little by little I had to deal with it. It was very heart-wrenching the first time I saw the rough cut.”

“It took me a long time to feel ready to do something like this because at the beginning, every time I looked at his pictures, it just became too much for me, psychologically” – Francesca Sorrenti

The relationship between fashion and addiction will always be fraught, as designers today continue to flirt with drug references: take Raf Simons’ ode to Cookie Mueller and Glenn O’Brien’s tragicomic play Drugs for his AW18 menswear collection (alongside some more tasteless references to the infamous heroin-addicted teen runaway Christiane F.), or the Moschino pill bottle purses Jeremy Scott sent down the runway for AW16, which were pulled from production for their implications of glamorising drug use.

The fashion industry is once again undergoing a moment of reckoning, grappling with its dubious treatment of models in very different ways: from sexual exploitation to the casting of underage girls, both of which the major fashion houses are only now beginning to fully address. “It’s not just models either,” says Francesca. “The industry is always taking advantage of young people in so many different ways. You’re seeing these big places use young photographers and stylists, but they’re taking advantage of them on an economic level. They say, ‘Let’s use these kids because they cost half as much’.”

But it’s not all about controversy. One of the extraordinary things about this moment was industry gatekeepers opening the door to a whole generation of young creatives, who have since gone on to become some of fashion’s most legendary photographers and stylists. It was a generational refresh that has rarely been repeated: and certainly at no other point in the history of magazine publishing would a teenager like Davide be commissioned to shoot his friends for a major magazine.

As Francesca remembers it, Davide’s intention was never to become a fashion photographer, but simply to document what was happening around him. It’s this, perhaps, that is what makes the images so staggering within a fashion context. “There’s a moment in the film where Davide is being interviewed by Richard Avedon, and he says something I always said: ‘It’s there, you see it, you shoot it’,” says Francesca. “I was so shocked seeing that because I don’t think he even remembered it was something I used to say. It was so beautiful to see that he thought about things in the same way as I did.” It’s a maxim that could apply to the entire generation. They shot what they saw, and not everything they saw was pretty. That isn’t fashion: it’s real life.