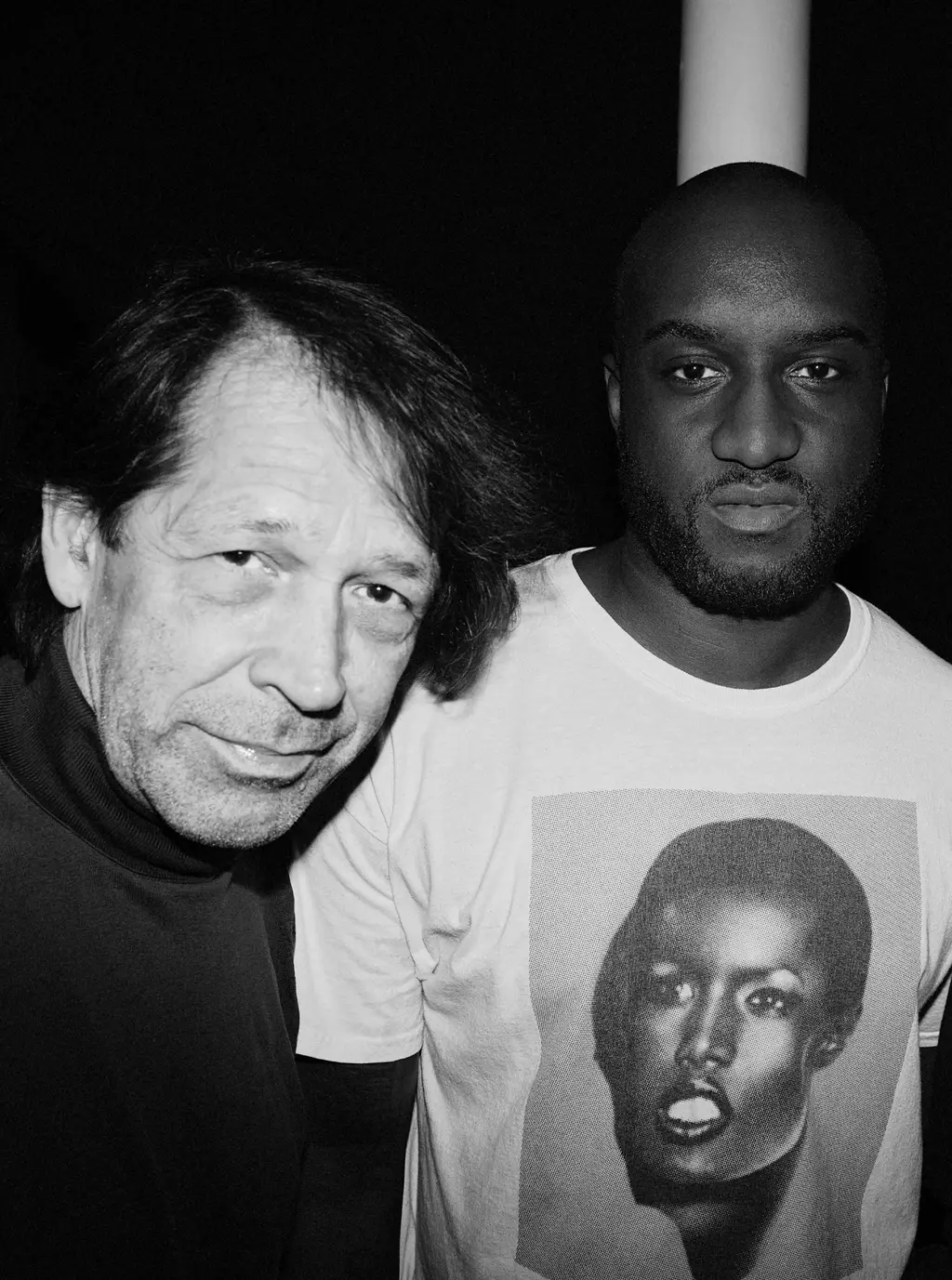

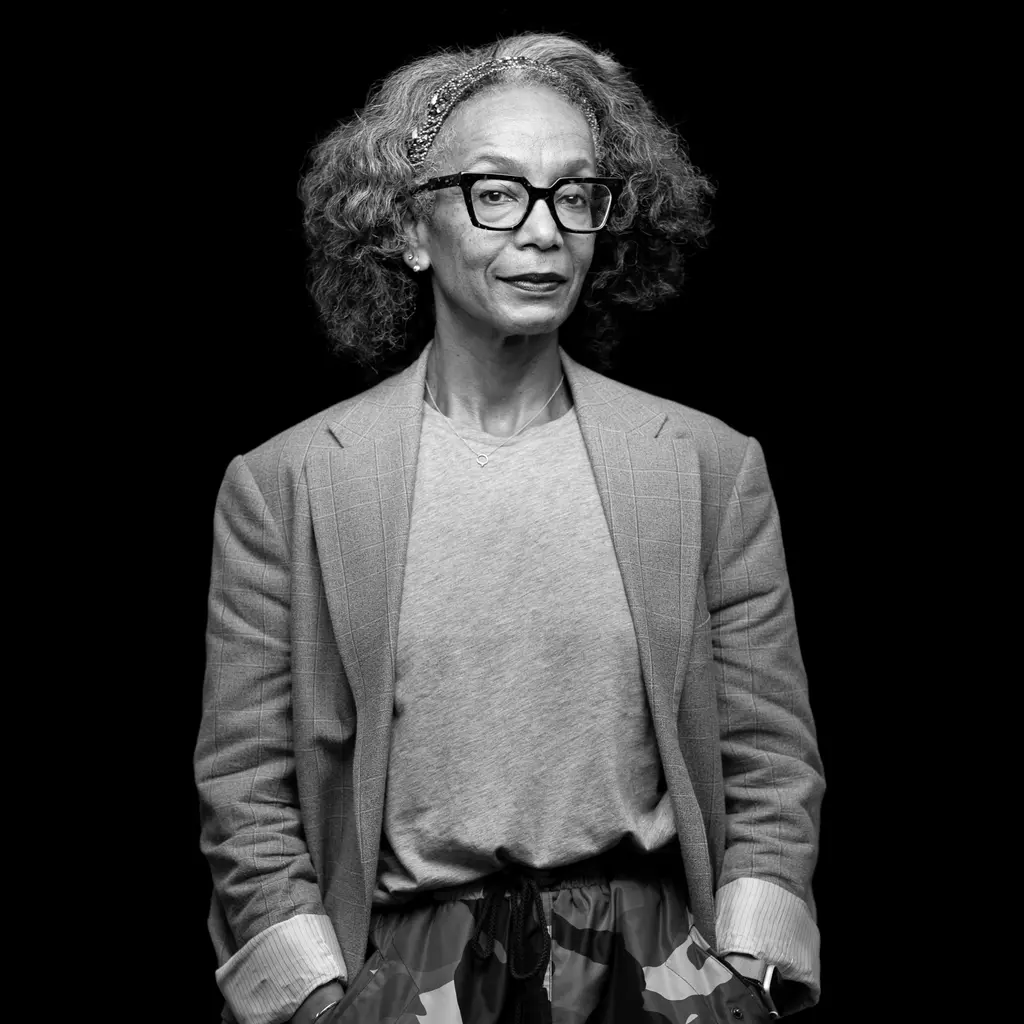

Robin Givhan on Virgil Abloh’s “short but seismic” career

In her biography, Make It Ours, the Pulitzer-prize winning author examines Abloh's impact and his place in the lineage of Black fashion powerhouses.

Style

Words: Shelton Boyd-Griffith

Virgil Abloh was a disruptor who worked like a designer, thought like a cultural theorist and built like an architect. He didn’t just remix the codes of fashion – he rewrote them. In Make It Ours, the first major biography of Abloh since his untimely passing in 2021, Pulitzer Prize-winner Robin Givhan covers all the bases: his life as a culture-hungry teen and his ascent as a creative director, to the days of Pyrex Vision and, of course, Louis Vuitton. But Make It Ours is no greatest-hits tribute. Rather, it’s a cultural reckoning.

“Virgil’s career was short but seismic,” Givhan tells THE FACE. “I wasn’t interested in writing a traditional life story. I wanted to understand the impact. The moment. What made the world ready for him, and what he did with that readiness.”

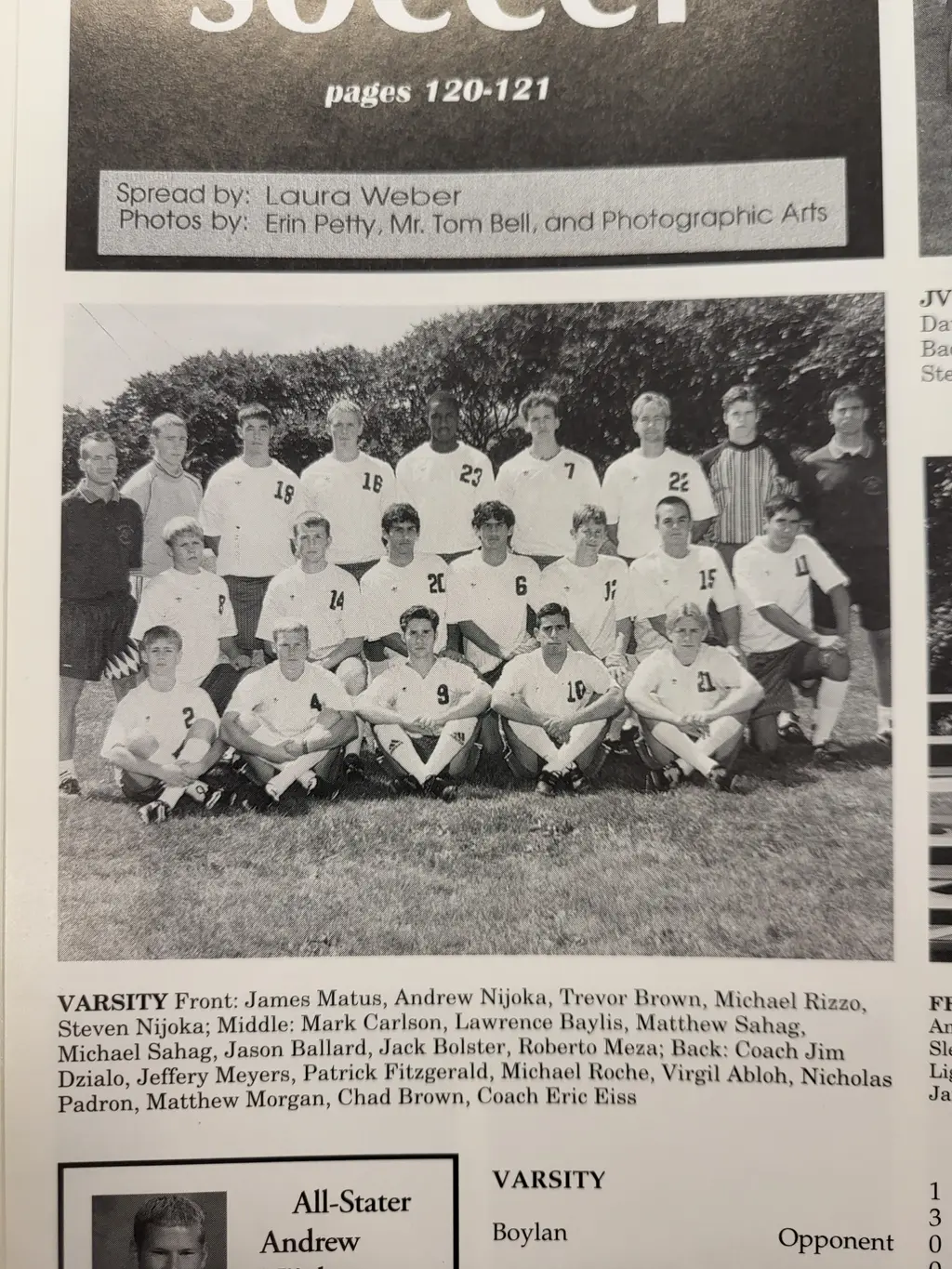

Over a tight 200 pages, she maps the rise of a Ghanaian-American kid from Rockford, Illinois, who would go on to become the most visible Black designer in the world. She never isolates him, instead interrogating the cultural, geographic and generational systems that made his ascent so powerful – and so improbable.

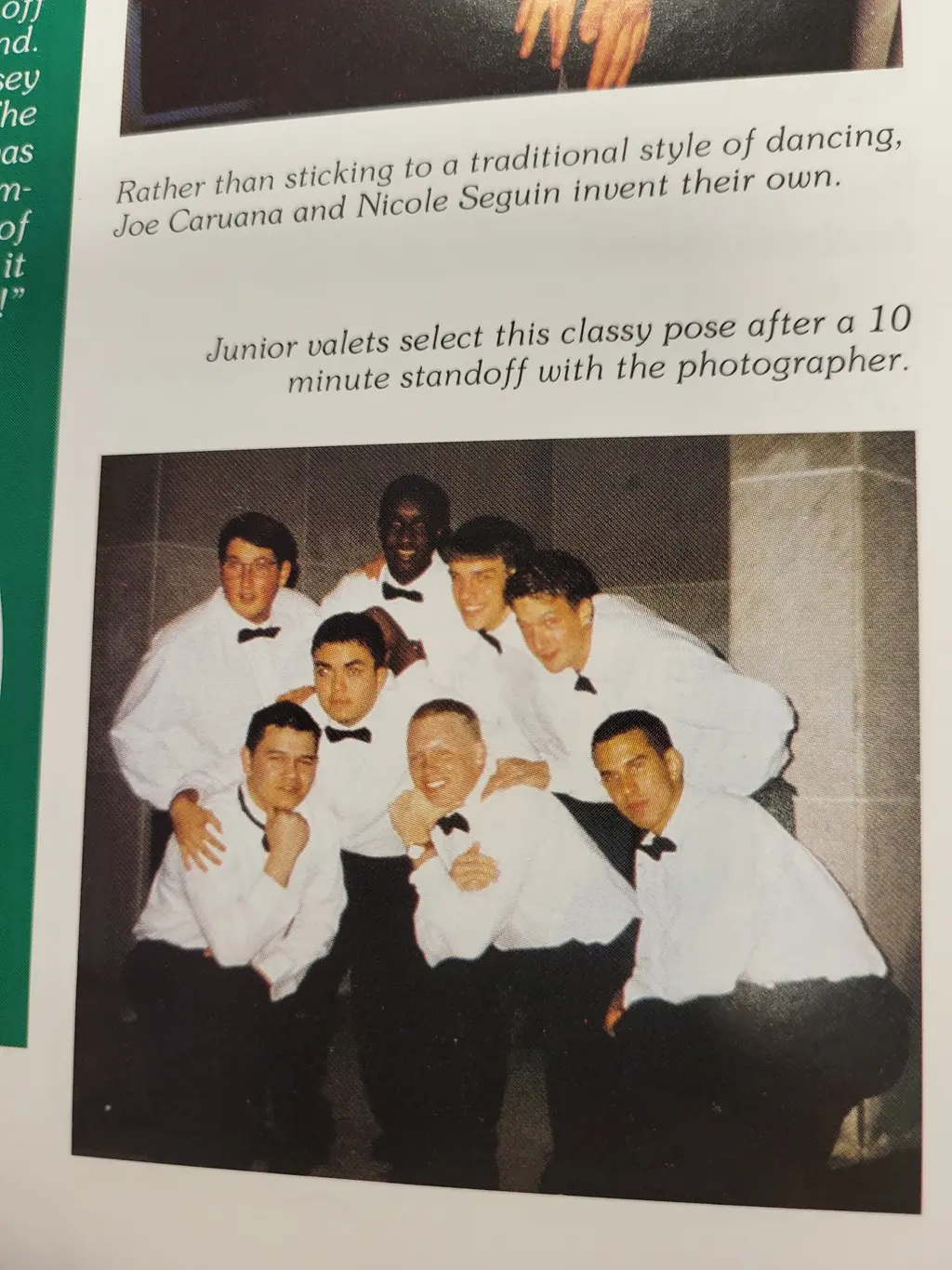

And so Rockford is where the book begins. “People like to say he was from ‘outside Chicago’, but that’s a stretch,” Robin says, laughing. “It’s closer to Iowa than to the city. A flat, segregated town with a literal river dividing Black and white communities. And yet that place gave him vision.” The son of immigrants, the circumstances Abloh inherited were different to that of his US native peers: “His family didn’t carry the generational trauma of slavery or the Great Migration,” Givhan says. “There wasn’t the same narrative of having to be twice as good. The assumption was: you already are.”

This mindset fuelled Abloh’s unorthodox path into fashion. No formal training, no apprenticeships under the haute Parisian guard, just a DIY portfolio of references: skate culture, Bauhaus, hip-hop, Raf Simons and Helvetica. “He wasn’t trained in the traditional sense, but he had a hyper-visual vocabulary,” Givhan says. “He knew how to speak through clothes – even if the construction wasn’t always perfect.” She’s clear about the importance of these imperfections: “I reviewed a lot of his collections. Some didn’t land. Some felt undercooked. But that was never the full story. Virgil’s legacy isn’t stitched into a single collection. It’s stitched into culture.”

Another thing Givhan is clear about in Make It Ours is that Abloh wasn’t an anomalous, singular genius. She places him alongside other brilliant Black designers such as Edward Buchanan (Bottega Veneta’s first design director), Patrick Kelly (the first American to be admitted to the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode) and Willi Smith (who had a huge impact on fashion in the ’80s) whose cultural legacy is often glossed over. “People forget that Black designers had already touched these luxury houses,” she says. “Virgil was the first to be widely celebrated, but he wasn’t the first to be there.”

What makes Abloh’s story different, the critic argues, is timing. “He was ready for the moment and the moment was finally ready for him,” she says. “Social media, the youthquake in luxury, racial justice uprisings – it all converged.”

And Abloh understood the power of convergence. He wasn’t designing for the critics, he was designing for his past self. “Everything I do is for the 17 year old version of myself,” he once said. That quote echoes through every chapter. “That internal reference point, it’s rare,” Givhan says. “Most designers look outward, at their mothers, at the movies. Virgil looked inward. He wanted to impress that curious, style-obsessed kid from Rockford.

“1997 was his big bang,” she continues. Abloh was (you guessed it) 17. Raf Simons was reshaping menswear. [Princess] Diana died. The culture was in flux. “That’s the air he was breathing, even if he didn’t know it yet”. Critiques, questions around authorship and originality, tensions between idea and execution – Abloh’s impact remains unquestionable. He broke doors down and helped others through. “He created a cheat code,” Givhan says, “and then he handed it out. He didn’t keep it for himself.”

Abloh’s collaborative, generous spirit is palpable in Make It Ours – hence the name. “I wanted the book to reflect what Virgil actually did,” she says. “He didn’t just make space. He made it ours. For the kids outside the system. For the creatives who didn’t see themselves on moodboards. He built something collective.”

Make It Ours: Crashing the Gates of Culture with Virgil Abloh, is out on 26th June