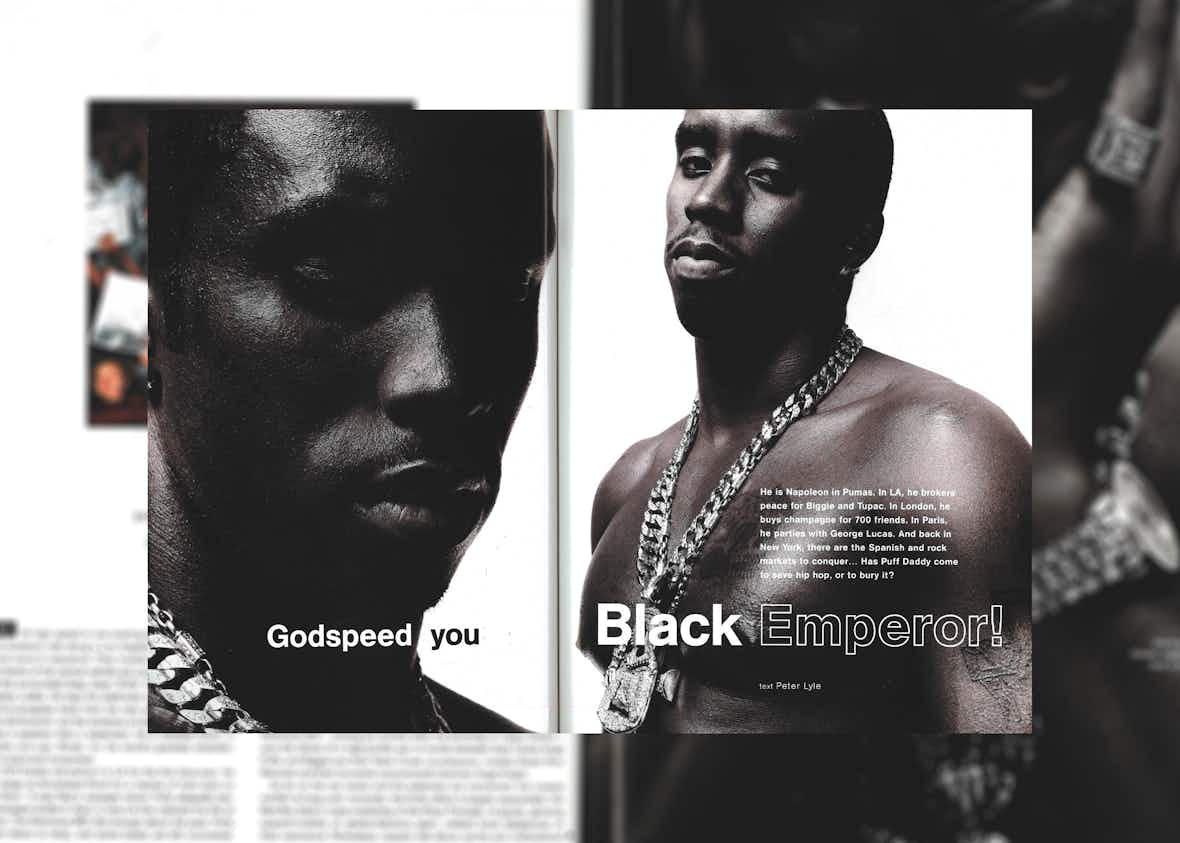

Godspeed you black emperor!

Black History Month: It's September 1999. He is Napoleon in Pumas. In LA, he brokers peace for Biggie and Tupac. In London, he buys champagne for 700 friends. In Paris, he parties with George Lucas. And back in New York, there are the Spanish and rock markets to conquer… Has Puff Daddy come to save hip-hop, or to bury it?

Archive

Introduction: Craig McLean

Words: Peter Lyle

Photography: James Dimmock,

John Spinks

To celebrate Black History Month, we’ve dug through our 40 years-deep back-catalogue to find interviews and profiles with the world’s greatest talents across film, music, fashion and the arts. Over the coming weeks we’ll be posting a selection of these Face encounters with the best of the best. Creative, resilient, revolutionary: these are our Archive Heroes.

Twenty years ago, Puff Daddy was the biggest noise in hip-hop culture, a multi-hyphenate before the phrase had been invented. The man born Sean Combs was, therefore, appropriately elusive. But after months of wrangling, The Face secured unprecedented access to the artist-entrepreneur who was about to rebrand himself as P‑Diddy. In a brilliant feat of reportage, writer Peter Lyle embedded with Puff in Los Angeles, London and Paris, while ace photographers James Dimmock (portraits) and John Spinks (fly-on-the-wall) captured the excitement and agitation surrounding every international move of the Playas’ Playa.

Today, we proudly republish the original September 1999 cover feature with the artist we must now (seemingly) call Sean Love Combs.

LOS ANGELES

At high speed in low evening light, a fleet of black Jeeps with tinted windows rolls along a Los Angeles freeway. They take up three lanes and move in sequence. They muscle in and out of traffic, ensuring that the flanks of the central vehicle are constantly covered.

In the back of the surrounded Jeep, Sean “Puffy” Combs takes another sip on his Belvedere vodka. He taps his shell-toes to the gloopy funk of Reverse, a work-in-progress track from his new album, Forever. “You can just hear this shit boomin’ out the windows on Eighth Avenue, right?” he asks. It is less a question than a statement. He is dressed down, in vest, jeans, shades and cap. Rarely for the world’s greatest entertainment mogul, he is quiet and composed.

In 20 minutes, Puff Daddy will perform in LA for the first time ever. He will join Nas on stage at Arrowhead Pond for a reprise of their duet on Nas’ Hate Me Now. It was Nas’ manager whom Puffy allegedly battered with a champagne bottle in April. It was LA that claimed the life of Puffy’s best friend, The Notorious B.I.G. But enough about the past. Puffy has a new album about to drop, and some bases are left uncovered.

Tonight is about business. Just in case, though, there are the Jeeps.

One of Puffy’s bodyguards gets a call on his mobile phone. The show, a multi-artist Summer Jam promoted by local radio station Power 106, is running 20 minutes late. “They got a dressing room?” Puffy asks, suddenly anxious. “I can’t sit in the car for 40 fuckin’ minutes.” Approaching the venue, Puffy notes the cordon of security guards and metal detectors with relief: “They ain’t playin’.”

This is not egomaniacal superstar paranoia. The 1997 death of The Notorious B.I.G. – coming six months after the shooting of Tupac Shakur – was the climax of a high-profile war of words between East Coast kings Puffy and Biggie and their West Coast counterparts, notably Death Row Records and their (currently incarcerated) chairman Suge Knight.

As far as the rap media and the salesmen are concerned, the coastal conflict is long over. Ironically, the Puffy effect is largely responsible. His Bad Boy label’s mass-marketing of the Playa Principle, of the gaudy, gloating upward-mobility of ghetto-fabulous glam, robbed local allegiances of their resonance. Nowadays, rappers talk about yachts and multinational investments. Nevertheless, Los Angeles remains the most gang-ridden city in the USA. There’s no way of knowing that someone, somewhere won’t feel that Puffy’s presence is some sort of insult.

Inside the arena, the event takes on even greater significance. The thousands of teeny hip-boppers out front, visible proof of rap’s vastly expanded, post-Puffy constituency, are being treated to a sonic sugar rush by the slick commercial radio staging. Backstage, meanwhile, the scene is set for some kind of hip-hop summit: LL Cool J is earnestly explaining to reporters his commitment to “representing” something or other “to the fullest”. Jermaine Dupri’s Atlanta protégé Da Brat, all beaded braids and brilliant white teeth, holds court off to the left. And, behind a barrier, a stony-faced group await their stage time. They are part of tonight’s headline act, the crew from next month’s The Chronic 2001 – the record which reunites Dr Dre with Snoop, Kurupt and Xzibit for a return to the 1993 smash that set the template for mid-Nineties rap’s fusion of 48-track sophistication and street-tough sentiments.

“The West rises again,” murmurs Nas, a small guy dressed big and baggy, as he leans against the dressing room wall and contemplates the Chronic all-star line-up.

Five minutes later, Nas takes to the stage. The unmistakable, Carmina Burana-biting boom of Hate Me Now echoes round the auditorium. He goes through the motions of the first verse then abruptly gestures for the track to be stopped. “Nah, nah,” he tells the crowd. “I can’t do it like this. We gonna start again, do it properly.”

It’s an old trick, but it still works its magic. On bounds Puff, shirtless, shaded, buzzing, sending gasps of amazement rippling through the crowd. “You can hate me now,” he chants, rolling his head, snaking his hips, flexing his newly beefed-up arms, “but I won’t stop now, ‘cause I can’t stop now…” Fans rise from their seats, all disbelieving squeals and hormonal shrieks. For them, Puffy is simply a bonus pop star.

Backstage, it’s a different story: some of the lower-ranking West Coast supporting cast watch Puffy on tiny TV monitors. Some snort derisively; most hang around ominously as the song climaxes. Brief performance completed, Puffy dashes off stage. He’s not about to hang around.

Unfortunately, the organisers want to present him with some kind of trophy, although no one seems to know what for. Puffy nips back on stage, dedicates his statuette to Biggie and Tupac, and dashes through the backstage area. Within two minutes, we’re back on the road. There’s no overwhelming sense of significance – Puffy moves too fast to brood on this kind of thing – but the tribute to Tupac has helped further relegate the East-West conflict to the status of historical curio.

“It felt good,” says Puffy with a toothy grin, slumping into the back seat of his Jeep. “It caught ’em off guard – they were all shocked. They would never expect to see me just perform out there like that.”

It may, he muses, have been “good to shock ‘em”.

Puffy’s compulsion to take the next uncharted step has been the crucial motif of his career. Sometimes his impulses backfire – most tragically in 1991, when a celebrity basketball match he organised in New York resulted in a stampede in which nine people died; or like in 1996, when he stoked the East-West conflict with an inflammatory interview in Vibe; or like in April, when he responded to a perceived slight to his Christian beliefs in Nas’ Hate Me Now video by attacking Nas’ manager.

But with every successful return on each successive gamble, the stakes increase. This year he secured an advance of $55 million from Bad Boy’s parent label, Arista. Alongside his five-year-old music empire, there are newer enterprises he’s founded on a scale that leaves no margin for failure: Bad Boy Management (now adding basketball players to its stable of performers and producers); a restaurant chain, Justin’s, named after his first son; Bad Boy Film, in production on their first feature, King Suckerman, a Puffy-fronted adaptation of George Pelecanos’s violent crime story about a Vietnam vet; Bad Boy Television, squarely pitched at the post-rap MTV market; Daddy’s House Recording Studios, New York locus of $100,000-a-pop remixes and home of Bad Boy’s versatile production squad, The Hit Men; Notorious, the “Maxim meets THE FACE meets Vibe meets Rolling Stone” magazine he recently bought; and Sean John Clothing (“The Future Of Fashion”). He is the multi-tasking producer, company CEO, urban tycoon and black role model in excelsis.

Then there’s the music. For his first single as an artist, 1997’s Can’t Nobody Hold Me Down, he sacrilegiously cut up Grandmaster Flash’s The Message and replaced the lyrics’ social angst with a rap about how great he was. Then he braved the ridicule of discerning pop-pickers everywhere by robbing Every Breath You Take from The Police for his Biggie tribute, I’ll Be Missing You.

No Way Out, the 1997 album that featured the latter single, sold rap to people who previously liked only pop. I’ll Be Missing You went to Number One in 18 countries, won a Grammy for Best Rap Performance, two MTV awards for its video, and somehow even an ASCAP award for songwriting. It was replaced at Number One in America by The Notorious B.I.G.’s Diana Ross-sampling, Puffy-starring Mo’ Money Mo’ Problems. This made Combs the only artist to match The Beatles, Elvis and Boyz II Men by dethroning his Number One with his own record.

Now, enriched and emboldened – “can’t stop me now” – Puffy has emasculated Public Enemy’s raging 1987 signature tune for PE2000, the lead single from Forever. Puffy’s second album also disinters the bones of another Radio 2 favourite, Christopher Cross’s Sailing, for a further mawkish BIG tribute, My Best Friend.

“I’ll always be entertaining in some fashion or other, whether I’m making my kid laugh or I’m in front of 30,000 people,” he says. “The screamers, they come and go. If I was addicted to it, I’d be sick, making records just constantly to hear the screaming.”

You want to believe him. You really do.

Although there is something ridiculous about his excess and ostentatiousness everywhere else, in the world of the pop video – home of the quickfire edit, the exaggerated effect, the extreme contrast – Puff Daddy makes perfect sense

The video diary of Sean Combs, age 29 ¾

Earlier that same day, Puff Daddy finds himself running between two high, flaming walls, dressed in shiny black Matrix chic and maniacally mouthing the words to PE2000 as huge black thunderclouds gather behind him. Then he does it all again, only now the sky has turned an equally epic Independence Day grey. Then a third time, with the heavens burning red and fiery in the distance.

Puff Daddy watches this sequence unfold on the small LCD screen in the back of his black Jeep. We are travelling from his Hollywood hotel to a Santa Monica special effects complex. Diamond-studded platinum cross round his neck notwithstanding, he’s wearing understated downtime uniform: dark, Carhartt-meets-Calvin jeans by Sean John, plain white vest and a pair of vintage Adidas Grand Prix. “I never really was a sneaker person,” he confesses. “I could never wear the new ones. I was straight with everything else, but not with sneakers. So I play it safe.”

Two weeks ago Puffy came to Los Angeles to film the video he’s now watching. This weekend – alongside the Nas gig, Puffy-supervised auditions for tour dancers, some more studio nipping and tucking on Forever, and a pit-stop at the Pasadena Rosebowl for the Women’s Soccer World Cup final – he’s back in town to see how he looks now that he’s surrounded by apocalyptic special effects.

The clouds aren’t working for Puffy. He’s unable to say how or why. “They look… flat,” he complains. “Can we get ’em more, like, 3D?”

Whether he’s planning a song, a video or a dance routine, Puffy’s artistic direction is consistently vague. “Make it sound… visual,” he tells the throng of comedians and assistants working on Forever’s inter-song skits. “Look like a movie, right?” he asks of a sound engineer who is working on the video. “Make it sound like one then.”

Puffy has never learnt the nitty gritty of turning knobs and adjusting levels. Instead, he reels off cinematic descriptions, makes noises, tells stories with his hands until the experts work out how to translate them into practical solutions. Puffy doesn’t even have a record collection. Conversely, his orchestration of business matters is staggeringly far-reaching yet precise. We’ve just passed a vast billboard for the new record and Puffy is keying a number into his hands-free mobile. “Hello? Yeah… s’Puff… That poster on Laurel Canyon’s garbage. You can’t see it properly when you’re driving past… Get me one on Sunset… Arista can get it… I don’t care, just do it.”

Arriving in Santa Monica, Puffy stands behind the effects artist manipulating the sky on her computer. He offers fuzzy suggestions and expresses impatience at the way she has to drag an electronic pen over a mat on her desk to alter the image on the monitor. “Don’t you just wanna do this?” he asks, tracing his finger across the screen and imagining instant results. “We should invent that and patent it! Make a whole lotta money!”

Next up, in a low-lit edit suite, he sprawls on a soft green sofa and watches the latest cut of PE2000, ordering the insertion of more crowd scenes. And then it becomes clear: although there is something ridiculous about his excess and ostentatiousness everywhere else, in the world of the pop video – home of the quickfire edit, the exaggerated effect, the extreme contrast – Puff Daddy makes perfect sense.

“It’s more about the total package with Puff,” he says, slipping into the third person, as he will often do in marketing mode. “You gotta get into the total package of the other artists on the album, the movie he’s produced, him as a performer, what he’s gonna do visually on the video. If you’re not looking at it like that, then you may be able to find problems with it.”

Bad Boy had foregone baggy denim, Timberlands and urban blues and gone all-out for a high-gloss aesthetic of white suits, speedboats and champagne

You may indeed. You may agree with the graffiti artist who, in 1997, adorned the New York subway with the legend “Puff Daddy Killed Hip Hop”. You might legitimately argue that he’s turned an authentic urban artform into theme park fodder. That he elbowed aside hip-hop’s archaeological instinct to locate forgotten treasures and reduced rap production to a game of karaoke with overfamiliar pop evergreens.

From the outset, anyone who cared about urban black American pop enough to buy a Bad Boy record knew that Sean “Puffy” Combs had been a significant factor in its creation. Not just because he made a point of murmuring phrases like “it’s all good” over his artists’ records, or turning up in their videos, but because the sound of Bad Boy was the Puffy-patented sound of hip-hop soul. At a time when rappers were still crying “no sell-out!” and watching from the sidelines as R&B borrowed their secret samples, accommodated their ideas and coated the results with a sugary, daytime radio sheen, Puffy turned the tables. Craig Mack’s Flava In Your Ear and The Notorious B.I.G.’s Juicy, the early Bad Boy singles that dominated the summer of 1994, welded hard, dirty hip-hop beats to huge, dubby basslines and slick, crisp synthesiser overdubs. Puffy had carved out a lucrative mid-point between the bland clarity of post-swing soul and the relentless grittiness of East Coast hip-hop.

A trailblazing, rule-rewriting sequence of singles followed. Biggie rapped on a record for Bad Boy girl group Total, they sang the hook on a remix for him – each exchange of talent successively broadening the audience of both acts. Then, just when people thought they had the measure of the Bad Boy ethos, Faith Evans’ 1995 debut Faith appeared, devoid of corny samples and guest rappers. It went platinum. After Biggie’s untimely death, his second album went on to sell four million. More remarkably, Ma$e, the substantially less-skilled rapper who went some way to taking Biggie’s place, landed another massive success with Harlem World. For all this and more, Puffy was lauded. But wherever he popped up, there was still no doubt: he was a label head and producer, not a performer.

Even after the success of No Way Out, Puffy remained inspired administrator first, rapper second. Combs repeatedly expressed reservations about being a performer, doubts about the likelihood of a follow-up, and anxieties about the unwanted pressures of stardom. As recently as last winter Evans – First Lady Of Bad Boy and one-time wife of Biggie Smalls – laughed when explaining how Puff ended up performing the only rap on her second album. “He doesn’t consider himself a rapper, in terms of being a real MC,” she said. “But commercially, right now, for the consumers, he’s the hottest rapper. So who else would I want?”

By this time, of course, Bad Boy had foregone baggy denim, Timberlands and urban blues and gone all-out for a high-gloss aesthetic of white suits, speedboats and champagne. Along the way, their records had become resident DJ Funkmaster Flex’s signature tunes at The Tunnel, the jewellery-flashing, Cristal-swilling New York nightspot which became the definitive mid-Nineties hip-hop environment. Most of all, though, Puffy and Bad Boy convinced hip-hop’s smaller-selling, artistically revered heroes – Nas being a case in point – to come over to their way of thinking. Puffy effectively redefined hip-hop laws according the larger logic of showbusiness. When kids from the New York housing projects met their heroes, they no longer came up and said: “Man, you got skills!” Instead, they exclaimed: “Man, you went platinum!”

Puffy has already staked his claim to the hearts and wallets of the country’s millions of Ricky Martin fans by working on the debut album by actress (and reputed Puff paramour) Jennifer Lopez

It’s midnight and, fresh from the Nas concert, Puff Daddy is ensconced in Hollywood’s Record Plant recording studio. He takes a call from Busta Rhymes, who is inquiring about his guest slots on Puffy’s autumn tour. Later, Puffy stops tampering with his album’s intro – all bagpipes, blisteringly bullet sounds and pseudo-Biblical oration – and asks someone in the shadows to “put that tape on”. It’s a recording of a recent news item. A pastel-suited anchorwoman gets no further than,”…police are still waiting to see whether Combs –” before Puffy mutters: “Shut it off.”

This is the latest chapter in the story that’s been dominating his public life since Puffy turned himself in to New York police in April and was arrested for assault. The reason? A pop video. Of course.

Having recorded Hate Me Now with Nas, Puffy agreed to appear in the song’s extravagant, Hype Williams-directed video. However, after consulting his church, he asked for footage of him carrying a cross to be removed from the video. The video debuted on MTV on 15th April, crucifix scene intact. That same afternoon, Puffy headed for the office of Steve Stoute, manager of Nas and lnterscope’s head of black music. According to Stoute, Puffy and two accomplices then beat him up and broke his arm with a champagne bottle. From the outset, Puffy ’fessed up to the incident – “I made an emotional, bad decision”; “It’s nobody’s fault but rny own” – but disputed the injuries and the use of the bottle. (The hospital which treated Stoute later confirmed that no bones were broken.)

Though the pending legal consequences may well eventually land Puffy with a slap-wrist sentence of some description, affairs between he and Stoute were resolved in June. Puff says they sat down and talked, settled things “man to man”, no strings attached. Other observers report a payment to Stoute of $250,000 and, more significantly, a deal which will see Stoute involved in a chunk of Puffy’s future business.

Another hour, another edit-suite. It is some sludgy time between two and three in the morning. Puffy has turned his attention to PE 2000: Rock Version, one of the single’s three mixes. The videos for the Radio Mix and Spanish Mix are already completed. Puffy, ever the marketing tactician, is clearly up to speed with America’s changing ethnic palette – within a few years, Latinos will form America’s largest ethnic minority. Puffy has already staked his claim to the hearts and wallets of the country’s millions of Ricky Martin fans by working on the debut album by actress (and reputed Puff paramour) Jennifer Lopez.

Puffy first got the “alt-rock” market in his sights when he enlisted cartoon metalhead Rob Zombie and Foo Fighter Dave Grohl for a remix of All About The Benjamins for a 1998 single release. Having sustained the interest of beards with his appropriation of Led Zeppelin’s Kashmir for Come With Me – his massive single from the soundtrack to Godzilla – Puffy is now out to maximise his impact in this market. Accordingly “P‑Diddy”, one of his many long-standing nicknames, will be his formal title for all future rock recordings.

“P‑Diddy fans hate Puff Daddy,” he says, emphasising the gap between the identities. “They just can’t get with that shit. P‑Diddy fans, they can’t believe Puff Daddy’s doing that shit when P‑Diddy records really make ’em feel that way.”

He turns back to the mixing desk, absent-mindedly prodding one of the diamonds in his two-inch-wide platinum bracelet back into place with a pen. Later on, as his crew chows down on a vast order of Astroburgers, he hears me yawn. “What was that?” he asks sternly, can of Red Bull in hand. “Those aren’t allowed.”

“Bad Boy is a brand. You’ve had them before: Motown, Stax, Def Jam. And he’s the embodiment of it”

Forever is the most crucial record of Puff Daddy’s career. It is also the most important event in the lifetime of the label he founded four years ago. The Notorious B.I.G., the label’s greatest star, may be long dead – although he is still credited as co-executive producer on Forever, and this autumn sees the release of Born Again, an album of Biggie raps, with music “written” by Puffy. Ma$e, Bad Boy’s post-Biggie sensation, has announced that he is giving up music for God. The news didn’t save his recent Double Up album from a lukewarm response.

Meanwhile, in a marketplace crowded with girl groups borrowing Bad Boy’s hip-hop soul template, even the latest offerings from Total and Faith Evans have not been huge successes. It’s all about the Benjamins, and Bad Boy’s gross revenue shrunk from $200 million in 1997 to $35 million last year. Now it’s up to Puff Daddy, the once-reluctant rapper, to reaffirm the label’s relevance – not from behind the scenes, but centrestage.

“It’s people from the outside looking in, not really knowing what’s going on,” says Puffy of speculation that Bad Boy’s fortunes are on the slide. “If you have a certain amount of high-intensity success and then reach some obstacles, then people are gonna think the worst. But I don’t think the worst. I’ve been going through obstacles and downfalls all my life. You just gotta take everything as it comes.”

As with all things Puffy, Forever follows PE2000 in being pretty much what you’d expect, only more so. There are appearances for the well-worn synth-funk loops of Club Nouveau’s Friends, Chaka Khan’s Ain’t Nobody and Earth Wind And Fire’s Fantasy. There are guest rappers galore (from new Bad Boy hope Shyne to Busta, Jay‑Z and Nas). There are guest singers from R. Kelly to Ronald Isley.

But there is also a new dimension. Forever betrays an awareness that the audience whose ears he opened to rap have been buying hardcore, barrier-pushing albums by DMX and Eminem. Puff’s grittier delivery, the rasping backing tracks to On and Reverse – it all suggests Puff’s ready, just in case the champagne bubbles have burst.

Bad Boy, says Puffy’s manager Benny Medina, “is a brand. A brand that stands for something. You’ve had them before – you think of Motown, you think of Stax, maybe you think of Def Jam – but it’s definitely a brand… and he’s the embodiment of it.”

Luckily, then, Puff has an ego and an all-excluding self-belief that’s up to the job. He was sacked from his first job, at discerning swingbeat label Uptown – reportedly for being too lippy, or too successful, too quickly. He used to have a habit of checking into hotels as “James Brown” or “Berry Gordy”. The inevitable, unfortunate double-bookings with the legends themselves caused chaos and embarrassment.

Best of all, former Uptown bigwigs Andre Harrell and Benny Medina, two men who made their names as hands-on, highly visible – but still suited and non-rappin’ – proto-Puffy executives, are now in his employ. Harrell, onetime Puffy mentor, is president of Bad Boy; Medina is Puffy’s manager. You’d think he’d relish the role reversal. You’d be right.

“They like my generals,” he says, veering into one of his favourite entertainment business analogies. “And I definitely feel like this is a war, you know? They have had the experience of me bustin’ they ass, basically. And them just respecting that. Like when we was competitors, them just takin’ that in. Them rememberin’ how intense it was, and just steppin’ their game all the way up.”

In 1999, the business of hip-hop is, without doubt, a battle zone. Like Master P, the Louisiana entrepreneur behind No Limit Records who wears camouflage and calls his artists “soldiers”, Puffy sells hip-hop with military precision and ambition. Last year, P was the tenth highest earning entertainer in America, a full five places above Puffy. Both figures loom large over the contemporary rap scene. But P has announced his plans to retire from rapping. He makes rubbish records. Nobody likes him, and he doesn’t care. He’s loaded. Puffy, on the other hand I wants your money and your love. Puffy wants it all.

Bad Boy’s agenda from the start has been to reach both the parts other hip-hop acts have never wanted to, and those where it was previously turned away at the door for wearing jeans and trainers

LONDON

On Sunday evening – video problems remedied, remixes fixed, dancers selected, album completion emphatically ongoing – Puffy flies from LA back to New York. On Tuesday, he lands in London. The next morning, jetlag and a rigorous sampling of the capital’s nightlife clearly no impediment to the job in hand, Puffy appears on The Big Breakfast. He smiles for the cameras and gets into the spirit of the programme’s primary-coloured silliness. He makes enough of an impact to distract viewers from Johnny’s million-words-per-minute schtick and Kelly’s two-syllables-per-minute suffering. Fluffy Puffy gives the great British public the chance to reflect that, well, that rapping bloke who fell off his motorbike in the video with the kiddie choir, he’s quite good, really. Nothing like you’d expect, is he?

“I got a lot of sides to me: I got the light side, the dark side, the happy side, the angry side,” Puffy will say. “The last two years weren’t, like, the happiest for me – promoting the album and everything, I’d lost Biggie, so I couldn’t give it all the pieces of me. With this album, I’m giving more of the pieces of me. You know, I’m just a regular person and I suppose it’s a surprise just for people to see me hang out, not fronting with no particular hip-hop image… I’m just a hard working man that loves to have fun and I wanna share that feeling with everyone else.”

As usual, Puffy is on a mission. He is in London, making his base in the posh Metropolitan hotel, and it’s a big deal. Last year, he flew the Bad Boy roster out for a virtual takeover of the MOBO Awards, where he infamously told Jimmy Guizar, husband of Spice Girl Mel G (née B), that he needed to keep “his woman” under control.

But this is the first time Bad Boy has made a fully-fledged promotional visit to Europe, and there’s a lot to do. Tomorrow, Puffy is throwing an album bash at the Café de Paris, vibe-free epicentre of the London celeb party circuit. London likes Puffy.

Puffy likes London, too. So far, in comparison with his success at home, he remains a newsworthy oddity here. But Puffy is Napoleon with Pumas and a swish new wavy hairstyle, and Britain must fall to his will. Bad Boy’s agenda from the start has been to reach both the parts other hip-hop acts have never wanted to, and those where it was previously turned away at the door for wearing jeans and trainers.

Hence the private jet which takes Puffy around the country and the Bentley in which he’s chauffeured around New York; the front cover of America’s high-earners’ money mag Forbes, arm around Jerry Seinfeld; the society parties at his Long Island home; and hence the fuck-you glee of the scene in the Mo’ Money Mo’ Problems video where Puffy wins a golf tournament. And now The Big Breakfast, a night out with the showbiz bloke from The Sun, and tomorrow’s recording at the Top Of The Pops studio. Puffy needs London because he hasn’t got one yet.

“One of my commitments on this album,” says Puff, like a benevolent emperor visiting a colony, “is to treat [the promotion of the record] like I treat it at home. I’ve been gettin’ a lot of love and a happiness to see me over here. So many cats that are into the music and the R&B, they respect me more as a producer than as an artist even. And then you have people who only know me because of Missing You. But I just wanna take it all – keep on keepin’ ’em happy and keep on keepin’ ’em motivated.”

Motivation is Puffy’s prime concern when he turns his attention to a spot of cleverly conceived community service that evening. Not his own, of course. The people who need motivating are the kids who’ve assembled in the main gym of the Brixton Recreation Centre. Puffy’s here to take part in a 20-minute exhibition basketball match featuring the NBA’s brightest new star, Allen Iverson, the Bad Boy All-Stars and local heroes the Brixton Topcats, with all proceeds going to Sickle Cell Anaemia groups.

It’s seven o’clock and, despite the early start and the jetlag, Puffy shows no sign of flagging. “I’ve always been intense,” he had stated earlier. “I’m a good loser if I lose at something, ’cause I know I’ve gone all out, but I love to win. I’m a competitor, it’s intense. If we have a problem, we have a problem, ’cause I’m gonna go all out. I’m not gon’ stop.”

Then, with no regard for the standard etiquette in these matters, the Topcats go and win the match by eight points.

“My philosophy is that every interview is a chance for me to make history. If somebody picks up this mag, sees this cover, l’m’a get my chance to exchange my point of view.”

Thursday morning. Puff Daddy lifts a silver dome and eyes his eggs Benedict with suspicion. He pokes a tomato quarter with his fork. “S’cold,” he says. “Get me another one.” In half an hour he will head to Radio 1 to go live on the Jo Whiley show. Right now, he heads out of the busy sitting-room where personal assistants and hairdressers and clothiers are making themselves busy, and into his bedroom.

For a moment, Puffy – father of Justin, five, and Christian, one, each from different relationships – looks like the proud, slightly world-weary dad that he did in the photos of a family holiday he’d had developed while we were in LA. Puffy looks at peace for the first time since we met.

In the usual manner of the Puffy whirl, this oasis of calm is brief. We are soon in the back of a Bentley, snaking through Soho side streets on the way to a very late arrival at Radio 1. The ever-alert workaholic is back in charge, on the phone. Is he really up to the back-to-back earnest indie interrogation promised by going live with Jo Whiley, and then recording an interview with Steve Lamacq?

“Man, this is history!” he responds emphatically. “People say, ‘Why do you bother with every interview?’ My philosophy is that every interview is a chance for me to make history. If somebody picks up this mag, sees this cover, l’m’a get my chance to exchange my point of view.”

Just in case someone misses this point of view, a camera crew has been enlisted to film his every public move in London for a documentary. That evening, The Metropolitan is once again Puffy’s palace, visited by suitors pressing for the emperor’s favour. “No photos, man,” says (a pre-shooting) Tim Westwood as he enters Puff’s hotel suite, putting a dampener on the endless Puffy publicity party. Typically, though, Westwood overcompensates by turning up in Sean John jeans and shirt.

Prince Naseem Hamed is wearing beige cords and shirt and lacquered black winklepickers. He is engaged in animated conversation with Ty, another of Puffy’s security guys. Naz is, of course, a one-time “rapper” himself – Walk Like A Champion, which he recorded with Brit rap crew Kaliphz, reached number 23 in March 1996. Tonight, he’s talking about his plans to next enter the ring to a Puff Daddy anthem. “We can still play the old record but everyone knows it now. Man,” he sighs, “imagine getting the best rapper in the world to do a track…”

“We can make it happen,” Ty replies, coolly. Nas looks overawed by the prospect. “I’m dyin’ for it, man!” he gasps. “Dyin’ for it.”

Puffy emerges from his dressing-room, groomed to perfection in a cream suit. “You’re coming to my party with us, right?” he asks Naseem.

“Well,” Naseem replies, “we’ve got the Bentley. You could come in my Bentley.”

“Nah!” says Puff, with a Jack Nicholson grin. “You’re comin’ in my Bentley!”

On arrival al the Café de Paris Forever party, Robbie and Beppe off EastEnders, Davinia Taylor from Hollyoaks, Elle McPherson and Chris Eubank and two-dozen anonymous, gorgeous and glossy-skinned girls await their moment with the guest of honour. Puff is B‑boy Barnum, managing to look attentive and intrigued at every unfamiliar celeb shepherded into his enchanted alcove. He racks up a champagne bill of several thousand pounds in the first few minutes. He works the room with mic in hand, occasionally making for the stage or the dancefloor to express his appreciation for the Bad Boy tunes his DJ keeps putting on the turntable.

In three hours’ time, when this party winds down, he will invite the 150-odd remaining guests up to the floor of The Metropolitan which he and Bad Boy have effectively taken over. Only an all-lights-flashing appearance by the fire brigade spoils the party.

Nevertheless, he insists, “it’s not for me to have a good time. I threw this party for the people, and I’m focused on that. I’m always alert. I done lost my man, I done lost my best friend, from maybe not being as focused as I should. I’ll never in my life not be focused on what’s going on.”

So if Puffy manufactures hedonist high life for everyone else’s benefit, when does he have fun?

“I enjoy myself when I’m just taking a nap and I got a pillow between my legs and a turkey sandwich with some apple sauce and a glass of lemonade. Then I’m straight like a motherfucker!”

Madonna gets up and does her Beautiful Stranger dance from her Beautiful Stranger video. George Lucas gets everyone’s tongues wagging by snuggling up to a teenage girl, until somebody explains that she’s his daughter

PARIS

Still, those invites keep rolling in. Two days later, on Saturday, Puffy flies to Paris. He is star guest at Donatella Versace’s Couture Week extravaganza. The journey passes with only one minor incident: Bad Boy rapper Shyne is almost arrested after calling an immigration officer a “fucking white racist bitch” when she forbids his entry into France. His Belize passport, it seems, is not accompanied by the necessary paperwork.

And so goes the show. Puffy spends the sit-down-and-eat-then-stand-up-and-dance party in the company of other beautiful people famous enough enough to go by one name: Prince, Naomi, Amber, Madonna. When the DJ plays Beautiful Stranger, Madonna gets up and does her Beautiful Stranger dance from her Beautiful Stranger video. George Lucas gets everyone’s tongues wagging by snuggling up to a teenage girl, until somebody explains that she’s his daughter.

Puffy fits in among these rarefied presences. He knows that all the middle-aged fashion, entertainment and media tycoons present – even though they have no interest in hip-hop and no shortage of wealth – are looking at him with envious eyes. Even they can’t help being fascinated by Puffy. And don’t even get them started on the Jennifer Lopez rumours…

After Tim Westwood is shot in south London the following evening, the British papers get their knickers in a collective twist about Puff Daddy and the negative influence of hip-hop. London’s Evening Standard warns Donatella and her fashionista floozy friends that, while it may be fashionable to like this aggressive gangsta rap chappie with a dark past, they may come to regret it in the long term.

But it doesn’t matter. Puffy still belongs. He can be debauched or dangerous and still the most desirable person to have on your guest list. He can hang with Elle and Robbie, Madonna and Jerry, kick it with Busta and shoot hoops in a dusty gym in Brixton. He can decide to be Tiger on the golf course or Keanu in The Matrix. He can make big, dumb, blockbuster rap that epitomises the era of the grand media event, cynically sell hip-hop heritage, hawk soulless sentiment as genuine emotion. He can have it all, and you can take from it what you will. Like he declared as he said goodbye in Paris, his whole suited and booted, soft-edged self even now crackling with competitive energy: “You don’t have to like what I do, and I don’t have to like what you do. But if you hate me, I hate you.”

You can hate him, but he won’t stop now. He can’t stop now.