Acting hard with British cinema’s toughest lads

Sweet Sixteen (2002). Courtesy of BFI

The BFI’s new programme pays homage to working-class men on screen, featuring films such as The Football Factory, My Beautiful Launderette and Sexy Beast – all of which tell us more about the class divide than any arthouse flick will.

Among the beloved character tropes of British cinema – the mardy teenager, the nosy neighbour, the pub landlady – there’s the hard man. He’s loud, tough, does what he wants, when he wants. He drinks a bit too much, and often sticks his boot in it. The “hard man” is usually found in the middle of a street corner scrap, perched at a pub, or somewhere in the terraces.

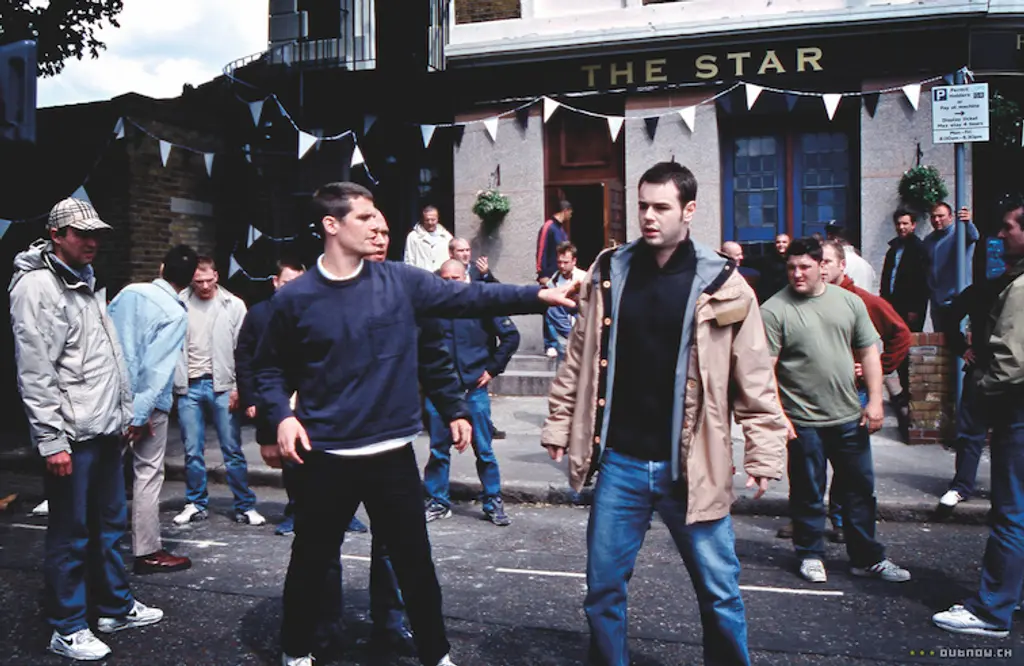

This is a character that’s evolved on our screens over the years: the tough, existential blokes of Karl Reisz’s kitchen-sink drama Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960); the yobbish punks of Stephen Frear’s queer classic My Beautiful Launderette (1985); the sun-tanned Costa del Geezers of Sexy Beast (2000); and the Stone Island-clad likely lads of The Football Factory (2004).

These great British blokes are given a hearty pat on the back in the BFI’s latest programme, Acting hard: working-class men and British cinema. With a line-up of screenings and events running from now until 2nd October at BFI Southbank, the series brings together said classics, plus Neil Jordan’s Mona Lisa (1986) and Gary Oldman’s Nil by Mouth (1997), as well as newer hits such as Saul Dibb’s Bullet Boy (2004) and Rapman’s Blue Story (2019). At the centre of all of these films are realistic depictions of the UK: housing estates, fractured families, boredom, anger, violence, all holding up a mirror to the nation’s wealth divide and class system.

“I have always felt quite frustrated with the film industry’s inherent snobbery, particularly in film criticism, of a certain working classness that we see on screen,” says the programme’s curator Nia Childs. “I think people really want to understand working classness through characters who are quite decent, or politically engaged. For me, there is so much to say about characters who kind of don’t care, or maybe are just completely disillusioned.”

Childs also recently curated a series of grime-themed short films for the London Short Film Festival, and has written and directed her own shorts Home (2022) and The Other End (2022). For her, Acting Hard is about taking the harder edges of these characters and repositioning them in a wider context of men’s mental health and the British government’s treatment of the working class.

It’s all too easy to take Danny Dyer, Ray Winstone or Stephen Graham’s film characters at face value: violent, angry, misogynistic and anti-social. There aren’t many redeeming qualities in many of the men they depict, but the point of Acting Hard is to figure out how they got there in the first place. The series interrogates the impact that failures in education, cuts to local funding, widespread poverty and, more recently, exposure to the internet have on working-class men.

“There is a fine line to tread when we are talking about violence, football and working-classness. You don’t want to give the false idea that working-class people are inherently violent and posh people aren’t,” Childs says. “But also, there is an inherent reality that is recognisable to those of us that did grow up working class, and I don’t think that these films make an apology for it necessarily – they’re just saying: ‘Well, this is how it is.’”

Working class people are one of the most demonised groups in the UK, but they’re also facing the most challenges. Acting hard questions why the men in these films – and real-life blokes walking down the street – should conform to a society that doesn’t serve them, particularly amid a cost of living crisis, a housing crisis and widespread industrial action.

“Why should these characters be decent people when they are having violence committed to them at a much grander scale than the violence that they are committing on other people?” says Childs. “Working-class people used to make up 50 per cent of our population. Those people get further and further marginalised, become more disillusioned and think: ‘Well, what can I do? I can’t do anything. So I’ll go and kick the shit out of someone to release some tension.’”

Film critics have long shoved Sexy Beast and The Football Factory in a corner with issues of Loaded, cans of Stella and a pack of fags. But forget all that. These are classics that tell us more about Britain, the class divide and the modern man than any poncy politician can.

Acting Hard, a season which explores representations of working-class masculinity in British cinema from the Thatcher era to the present day, is playing now at BFI Southbank until 2nd October