Ai Weiwei: “Ukrainians would give their last drop of blood to fight”

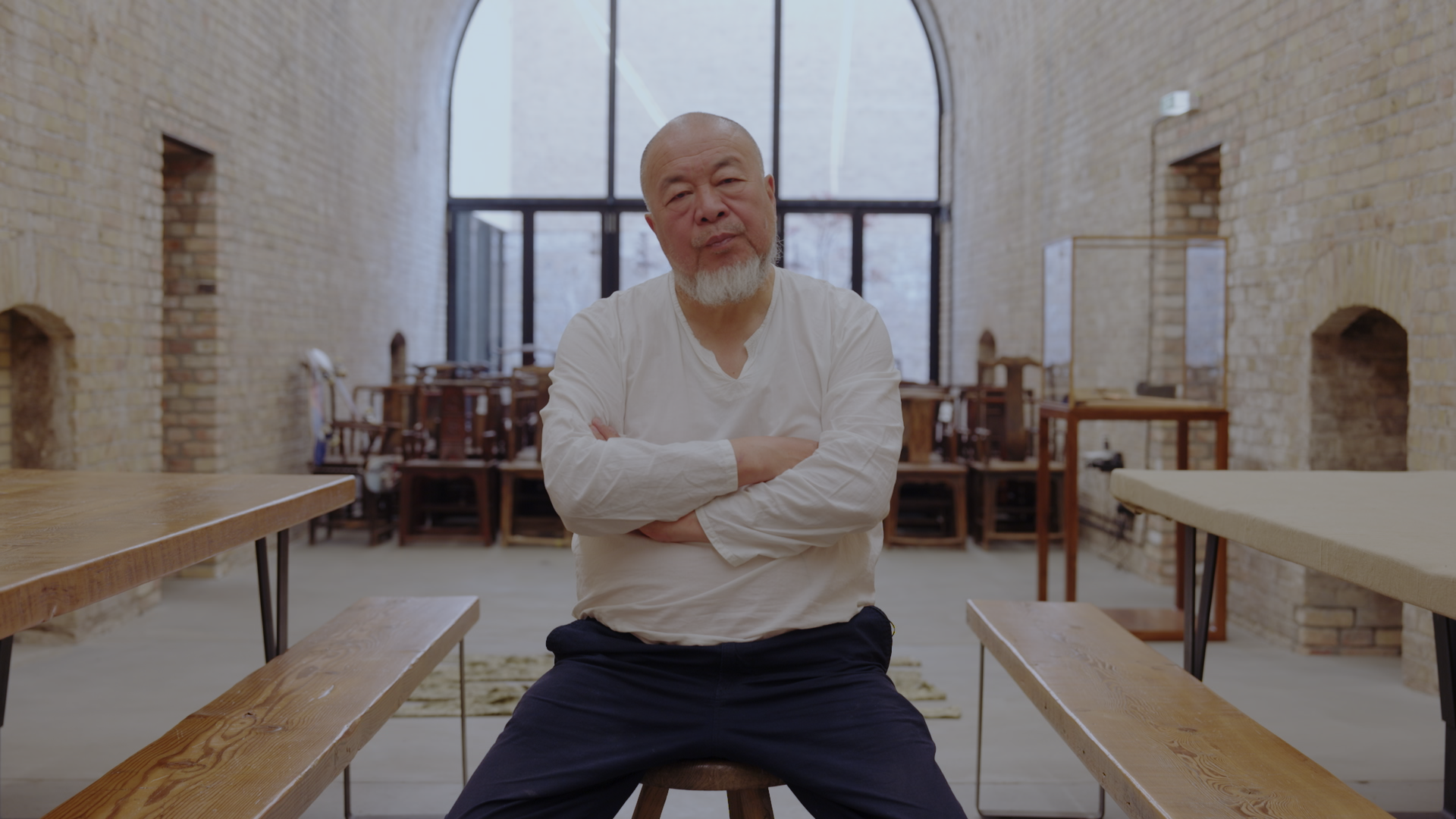

Ahead of his new exhibition in Kyiv, THE FACE visits Chinese artist Ai Weiwei in his Berlin studio. Unsurprisingly, he was as wise as he was witty.

Culture

Words: Tiffany Lai

Ai Weiwei is holding a large, cleaver-shaped piece of jade. Perfectly smooth, cold, and the colour of deep, marbled moss, he passes it to me over a wooden table in Berlin.

“This is a piece from the late Neolithic period,” he says, solemnly (Weiwei says everything solemnly). “It’s 4000 years old.” He has barely got the sentence out before the ancient ritual object is safely back in his large hands.

We’re sitting in a 30,000-square-foot underground studio in the German capital, which Weiwei renovated from a former brewery after leaving China in 2015. Airy and sunny, it’s covered by a towering, cathedral-esque ceiling with huge windows, flooding the space with light. Rooms are segmented by open doorways, and at its centre sits a shadowed communal kitchen shared by the hushed, polite team that work in the 68-year-old artist’s HQ.

But back to the jade. Weiwei hands over a second, much lighter-coloured piece this time – it’s a hand-carved, hollow cylinder with four corners, a circle within a square. “This is called a cong,” he explains. “It’s from the same era: cong manage the earth and bi [flat, disc-shaped jade artefacts] manage the sky.”

These priceless pieces happened to be on the table when we began our conversation, and they offer a glimpse into the artist’s personal fascination with the material.

“I probably have the biggest private collection of early jade [in the world],” he says. “It’s mysterious. Why did the Chinese race have such an early respect [for] an unknown universe? It’s almost 6000 years ago but still, today, they relate to jade culture. It’s very hard for people outside of China to understand that.” Sure enough, it continues to hold a strong cultural appeal, often worn to promote health and prosperity for the wearer while acting as a protection against bad luck.

Beside the jade artefacts on the table lay another Chinese product, one that also has the ability to prompt quasi-religious feelings from its collectors: a pair of box fresh Nike trainers. Weiwei has purchased these not for their ability to summon 6000 years of Chinese spirituality but, rather, because they have zips instead of laces.

“I’m going to Ukraine, so I have to wear something I don’t have to tie. It could be muddy, unpredictable terrain. I wore the same kind of shoes for Human Flow,” he says, referring to his ambitious 2017 documentary that closely followed the exhausting journeys of migrants worldwide, trudging from one border to the next.

The Beijing-born artist is preparing to return to the active warzone of Kyiv to present a new exhibition after visiting last month.

“Normally, I don’t want to get involved with situations like this,” he says, referring to starting an art piece in relation to the war, “because I know if I get involved, I’ll be completely involved. Almost like a love affair.”

Originally asked to exhibit in Kyiv two years ago by Ribbon International (a not-for-profit platform dedicated to preserving contemporary Ukrainian art and culture), Weiwei hesitated for two years, fearing that it would take over his life. But in the end, after the war broke out, he gave in.

Having worked with artists such as Wolfgang Tillmans and Barbara Kruger as well as local artists like filmmaker Oleksiy Radynski, the organisation is now preparing to open Weiwei’s exhibition on 14th September at Pavilion 13, a minimal Soviet-era exhibition hall-turned-cultural centre in Kyiv.

There, Weiwei will unveil the snappily-titled Three Perfectly Proportioned Spheres and Camouflage Uniforms Painted White. In the next room over from where we’re sitting, there are large scale models of these pieces. But first, he wants to show me something on his phone.

“The biggest surprise to me was the Ukrainian train system,” he says, pulling up a video he took on a platform of Kyiv central station last month. “It’s very old, they still use machines from the Soviet-era in the factories. Now, only the train works, so they have to bring soldiers to the front and carry back the wounded later in the day. It’s surreal.”

On the screen, a blonde woman in a ponytail is holding on tightly to her army uniform-clad partner in front of a train. With downcast eyes, their fingers press tightly into each other’s backs. The platform is crowded, though strangely hushed. Weiwei’s camera feels impossibly close and the temptation to look away from such a profoundly intimate moment is immense. But to look away from a scene like this one feels anathema to man who has spent almost his entire career asking to face reality head on.

“These people are not soldiers, they’re drafted from all professions” he says, as a middle-aged man with a prosthetic leg limps past in uniform. “Some are 50 years old and they still go back [to fight]. It’s very sad. No one goes willingly.”

But for Weiwei, one thing is clear: “They will never accept Russia taking over. If you ask them, ‘Do you think you can win?’ nobody answers, ‘Yes’. But they say, ‘We have to fight’ and that touches me. What is ‘winning’ anyway?”

He flicks to a video taken from later in the day. A soldier swaddled in bandages up to his nose and bound to a stretcher gets taken off the train in the evening, where a carriage has been transformed into a mobile ICU unit.

“It’s very peaceful, nothing dramatic,” he sighs. “It’s kind of horrifying for me because you see the war completely accepted. You can see that they’re desperate, yet they would give their last drop of blood to fight.”

“I think that animals are at their most vulnerable during wars and they’re often hurt and neglected. But they’re alive, like humans, so I use them to symbolise life itself”

These videos were taken on Weiwei’s last visit to the country, where he had overseen the formation of Three Perfectly Proportioned Spheres… in a Ukrainian factory. The piece consists of three core metal forms that look like hollow footballs reaching up to about nine feet in height. Made up of connecting pentagons and hexagons, the shapes have a long history in the Ai Weiwei universe.

Over 15 years ago, Weiwei became fascinated by one of his cat’s toys, a hollow ball shaped like a football with a bell in the middle. Drawn to its geometry, he challenged his carpenters to replicate the shape using wood for a large sculpture, only using Chinese carpentry techniques i.e. no nails, just joints cut at perfect angles that click together seamlessly.

It took them an arduous two years to achieve a result. During this process, Weiwei went to a bookshop and coincidentally came across the shape in a 16th century mathematics book about golden ratios, illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci.

“I said, my God, the drawing is exactly like what our carpenters achieved. So that’s why I named the shape after the book: Divina Proportione.”

For Three Perfectly Proportioned Spheres…, the forms will be covered by a buttoned-together layer of custom material designed by the artist. From afar, it looks like traditional camouflage, but upon closer inspection, layers of army green pixelated cats appear. Why cats?

“Firstly, I like cats,” he says, simply. “Second, I think that animals are at their most vulnerable during wars and they’re often hurt and neglected. But they’re alive, like humans, so I use them to symbolise life itself.”

Lastly, each sphere is covered in a wash of thick white paint. Covering the material wasn’t always the plan, but he idea came after a Ukrainian architect pointed out that some of the soldiers’ relatives might find the camouflage motif insensitive – perhaps they wouldn’t want to see cut up uniforms in a gallery, even if they were covered with cats.

“I don’t agree with her, but we’re in a warzone,” he says, shrugging. “People are dying and that could be a reality. And I always consider other people’s opinions.” So, he painted over it.

“It reflects something about value and judgment. How close do we want to be to reality? Do we feel more comfortable when reality doesn’t feel so real?”

Like much of his previous work, Three Perfectly Proportioned Spheres… plays with the tension between what we know and what we see. For Weiwei, it’s world leaders such as Trump, Netanyahu and Putin who have really mastered this game of obfuscation.

“There’s a piece of writing from [The Art of War author] Sun Tzu. He says, ‘To use a strategy that is based on lies always works’, because you never know which act is real. Those [politicians] are playing a poker game. They can flip everything in an instant. The worst thing is you don’t believe anything they say, so you can only take the consequence. Democratic societies become much more vulnerable when there’s no consistency.”

For much of his life, Weiwei’s inclination to expose systems and provoke audiences have gotten him into trouble.

I tell him that I’m a little surprised to meet him here in Berlin as opposed to his other bases in sunny Portugal or Cambridge, where his son lives – I had the impression he didn’t like Germany very much. “I don’t love it,” he says, deadpan, referring to a Guardian article in which he is critical of what he views as a form of ideological exceptionalism in the country.

“I’m always criticising and nobody likes someone who’s criticising all the time,” he says. “I guess they think I can’t criticise them because [Germany] saved my life [Weiwei was offered a German work visa in 2015, enabling him to live and work in Berlin] but nobody saved my life. If you support me, you support my ideology, not me as a person.”

In the end, Weiwei says his son Ai Lao was the main motivation behind his move, with the city providing a stable environment for his upbringing. But that, too, comes with its own challenges: Weiwei fears that Ai Lao, now 16, will become what he calls part of the “greenhouse people”, a metaphor for modern comforts defined by “perfect temperature, perfect humidity”. Too much of that and he believes we become like plants grown in lab conditions: always comfortable.

“People don’t know how tea, [for example], is grown,” he says, gesturing to the brew on the table, “or how to make anything. You can just buy everything. Nobody can refuse comfort or material obsession. AI can answer any question. We’ve become a new race, one without knowledge or respect for essential survival skills. We’re living in a very different world.”

Weiwei often speaks like this. It’s as if he has been here much longer than the rest of us, or that he at least has the advantage of a bird’s eye view on society. With his firmly planted feet and wise, weighty cadence, there is something of the mountainous about him, simultaneously grounded and slightly otherworldly.

As our conversation draws to a close, Weiwei returns to the art pieces that brought me here in the first place. Despite his emotional closeness to the war and the graphic scenes on his phone, Three Perfectly Proportioned Spheres… remains – visually at least – situated in the abstract realm. I ask if he, like Susan Sontag, thinks that the violent images of war we’re constantly exposed to run the risk of numbing us.

At the mention of Sontag, Weiwei brightens. “I met her in the late ’80s. Allen Ginsberg introduced her to me.” At the time, he was living in the East Village and doing street portraits for people on West Fourth Street. “I was making drawings for $15,” he says, smiling.

“But I completely agree [with Sontag]. There are certain things you should not see. By seeing them you are changed, and if you are not changed, then you are tolerating them. Every image we see is a challenge to our moral condition.”