Andrea Arnold always wanted to make Bird

The new film from the queen of indie cinema features luminous performances from Barry Keoghan, Franz Rogowski and newcomer Nykiya Adams. The director tells us about making magic with limited time and resources, and her knack for chronicling the comedown of growing up.

Culture

Words: Jade Wickes

Andrea Arnold, if she can help it, prefers to steer clear of explaining her films.

“I want it to explain itself,” the director says, settling into a plush office chair in an even plusher North London office belonging PR company for her latest movie. “Talking about my work is quite tricky, because it can take away the fun of people going to see it. At galleries, when they put all those explanations on the wall, I never want to read them. I want to experience it myself.”

It’s just as well: you’re better off going to see Bird as free from the shackles of “synopsis” as possible. But for the sake of this article, we’ll touch on the basics.

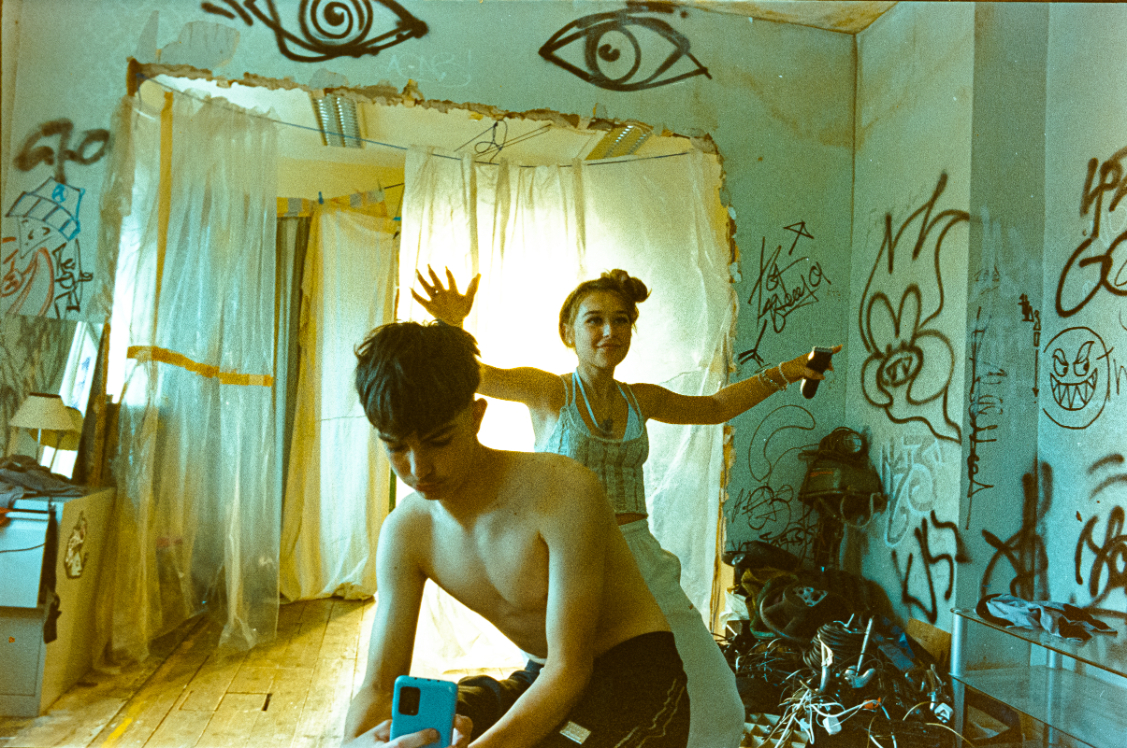

Bailey, a 12-year-old played with bristling jadedness by first-timer Nykiya Adams, is growing increasingly bored of her life in Gravesend, Kent. Her dad Bug (an always-brilliant Barry Keoghan) is, at best, an irresponsible parent. He has two things on his to-do list: getting married to new girlfriend Kayleigh (Frankie Box), who Bailey hates, and making cash by harvesting hallucinogenic slime from a toad he’s had imported from the US (yes, really).

She looks up to her brother Hunter (Jason Buda) and wants to get up to no good with him and his mates, but he won’t have any of it. So Bailey daydreams and turns her phone camera onto birds – a pastime which brings her some calm amidst a world of non-stop chaos. That’s until, one day, she meets an unlikely new friend, played by Franz Rogowski (Passages), who helps her start to figure things out for herself. His name? Bird. The rest? That’s up to you to find out.

Arnold, 63, cast Keoghan as Bug before both The Banshees of Inisherin and Saltburn came out, thinking mainly that “his face was so arresting” and trusting the gut of her longtime casting director Lucy Pardee. Needless to say that choice paid off. Arnold describes Rogowski, meanwhile, as “an absolutely beautiful man. I just completely loved him and Barry.”

The process of finding the perfect Bailey was a little less straightforward. She was looking for someone mouthy, jokey and rude. Coming across Nykiya while visiting different schools in Essex, something stood out. “She was more internal, but she made me sit up. I can’t necessarily tell you why, but that feeling never really left me.”

Nykiya, now 14 (12 when they shot the film), grew up watching EastEnders and Top Boy. She saw some of herself in Bailey: a headstrong fearlessness and a desire to find something outside of quotidian life to latch onto. “I wasn’t really acting sometimes,” she tells me when we talk during October’s London Film Festival, where Bird had its UK premiere. “I was reacting and exaggerating that reaction, because Bailey dealt with things in extremes. It was about dialling that up.” Her favourite thing about the experience? “The food!” Nykiya says, laughing. “I got takeaway for two months straight. Living life.”

In many ways, Bird is typical Arnold fare: social realism and kitchen sink drama. It’s a sharp, gritty story about coming-of-age and the resilience of children in the face of adults who should know better, even if they’re downtrodden by poverty or drug addiction. The filmmakers’ heroines are often runaways, outsiders, young women who don’t take any shit. Bailey is no different. There’s a deftness to the way Arnold approaches this kind of subject matter, too, not least because it’s rooted in the very fabric of who she is: born in in Dartford when her mum was just 16, Arnold was one of four siblings who grew up on a council estate in a single parent household.

The challenges that come with such a background, then, are hardly out of reach. Consequently, this narrative arc is one that she’s previously explored to varying degrees: in her Oscar-winning 2003 short film Wasp, 2009’s Fish Tank and 2016’s American Honey, to name the holy trinity (though Bird is sure to soon be joining the canon). All of these filmic wonders have helped establish Arnold as a prolific director whose touch is unmistakable: fluid, ingenious, alive.

“[The idea for] Bird had been in my mind for ages, really,” she says. “I started talking about it, then I started writing it. I stop and start. Some of the early writing was quite different. But I think in the end I always get to the place I intend – not that I have any intentions, because I always try to just explore and see what comes. But as the years pass, you change, and perhaps the Bird I would’ve made back then is different to the one I made now.”

Instinct is at the heart of Arnold’s approach, always. She’s led by feeling – and if that’s missing from a scene, it won’t make it onto the page. Shy of admitting whether or not Bird reflects her own transition from girlhood into adulthood, at least “the feelings are very true to me”, as she puts it. “I couldn’t have done Bird otherwise.”

Arnold, then, is a hunter gatherer of feelings. In a previous interview, Franz Rogowski described her as such – as someone who “would wait for the right moment to come […] for hours and hours, to wait for a bunch of kids to calm down until they could walk across a meadow and own the meadow and be in their own territory, instead of being forced to pretend to do something naturally”.

This is often what makes Bird such an interesting watch: you get the sense that Arnold has carefully put each set piece together, creating the perfect environment for curated narrative chaos to ensue.

“I don’t know that I quite have the luxury of hunting in the way Franz describes,” she says. “What I do is that I allow things to be. I don’t push, I don’t control. All my films are low-budget, which means limited time, and that’s always been the thing with me. There’s no money which means there’s no time, so I have to find that balance. If something doesn’t want to happen, you have to let it go. But another thing always takes its place.”