“Art and good nature can change the world”

We talk to the Virgil Abloh about his mid-career retrospective at Chicago's Museum of Contemporary Art.

Culture

Words: Shonagh Marshall

In his seminal text Ways of Curating (2014) Hans Ulrich Obrist writes: “At its most basic [curating] is simply about connecting cultures, bringing their elements into proximity with each other – the task of curating is to make junctions, to allow different elements to touch.

“You might describe it as the attempted pollination of culture, or a form of map-making that opens new routes through a city, a people or a world.”

Although Virgil Alboh doesn’t label himself as a “curator”, Obrist’s definition fits both how his work is perceived, and how he has positioned it. His greatest strength is to take elements from multi-disciplines and cultures that could seemingly be very disparate, complex and nuanced and connect them, instilling bite sized nuggets to be disseminated. It might be easy to dismiss this but it is a skill that can’t be honed – it is instinctive – and Abloh is having a really, really good time using his.

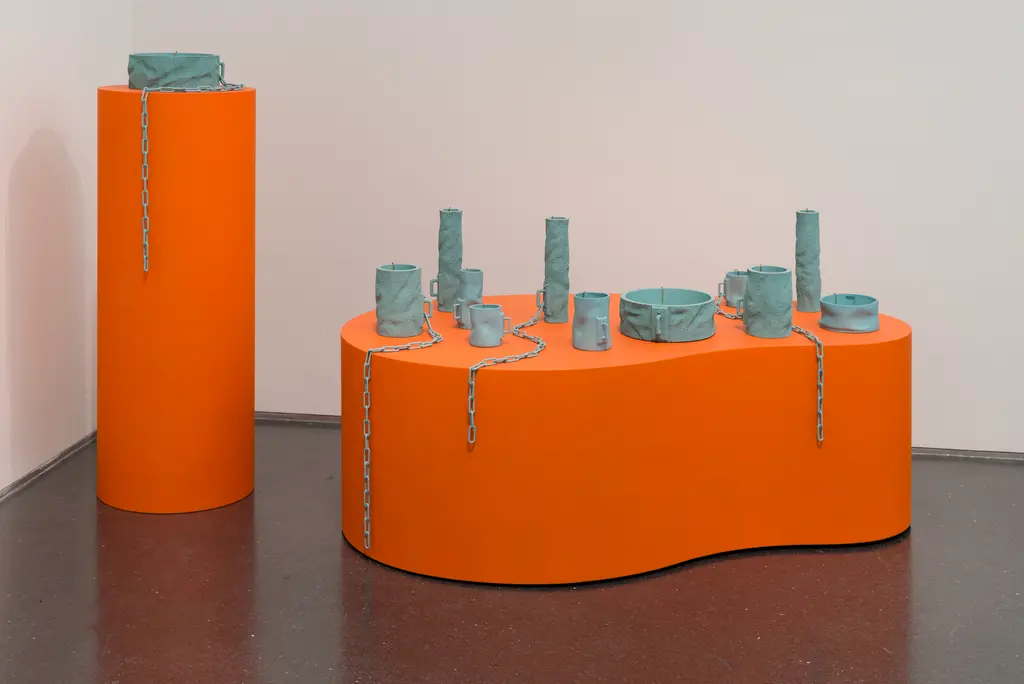

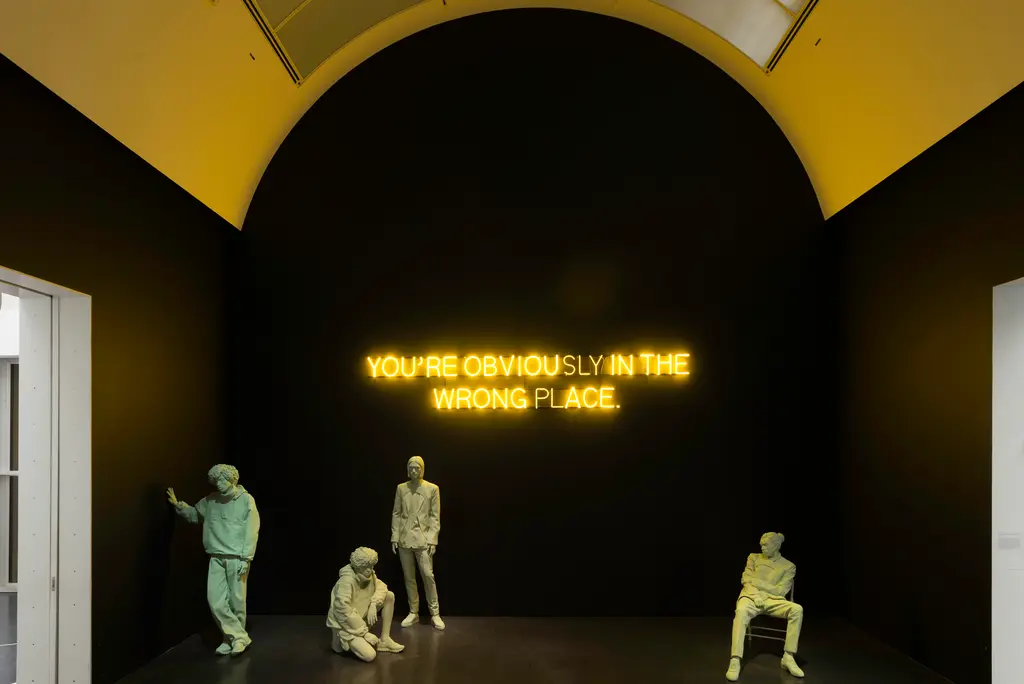

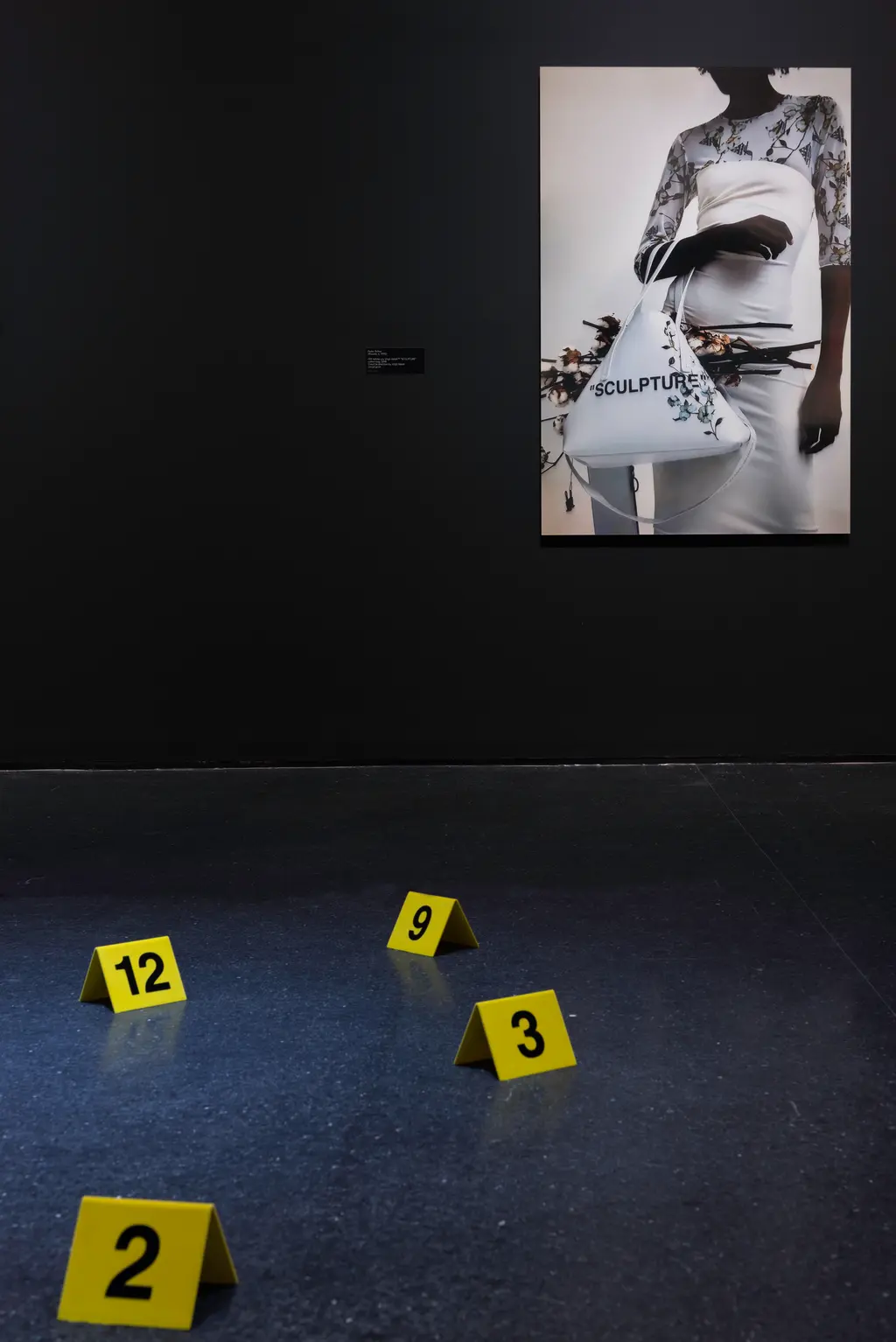

This month, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago opened a mid-career retrospective of Alboh’s work, entitled Virgil Alboh: “Figures of Speech”. The exhibition is made up of installations throughout the museum that evoke the retail experience, displaying garments, images and films documenting his work to date from his first label Pyrex Vision, Off-White founded in 2013 and his current role as artistic director of Louis Vuitton menswear. It also includes a shop called “Church and State” embedded on the fourth floor, public art commissions throughout the city and a heavyweight events programme. If this brings an audience to the museum that has never been before, or wouldn’t usually go, which it undoubtedly will, it will be celebrated as a resounding success. Perhaps it may change someone’s mind about culture… after all isn’t that what museums are supposed to do?

How often do you go to exhibitions, galleries or museums?

For me, a huge part of my travels is experiencing the local design and art offerings, and taking in the different ways that these places and cultures choose to showcase works that have been deemed culturally significant for whatever reason. I try to visit inspiring exhibitions everywhere I am.

What was your eureka moment? The moment you saw or heard a piece of work that moved you – where you thought instinctively, I really understand this and, in turn, it inspires me.

I think there’s been a lot of eureka moments; I wouldn’t necessarily peg anything to one moment or one occurrence that I can pinpoint as a turning point. I come from a place where I was trained in different influences. I was first trained as an architect, learning the practice of OMA, led by Rem Koolhaas. They were creating a type of architecture that allowed me to think beyond just constructing buildings, but affecting the cultural landscape through the lens of architecture. I think I’ve taken that with me across everything I do.

If I bumped into you in an elevator and gave you two sentences to drill down on what the exhibition was about, what would you say?

I believe that art and good nature can actually change the world. I refuse to believe the opposite.

“My optimistic hope is that this can be a cool alternative to more dangerous lifestyle choices people sometimes make.”

What was the draw to stage a mid-career retrospective? Why not develop a site-specific installation or a newly commissioned body of work for MCA?

It was really about taking all of these things from 1989 to now and looking at them as a broad scope. Demonstrating how I’ve wrestled with concepts over time, how things have evolved, how I’ve evolved from a consumer to a producer. I thought that this was also the perfect place to tackle my point of view about how race informed my work, and then Samir Bantal [Director of AMO, a think- tank founded by Rem Koolhaas in 1998] and Michael Darling [MCA Chief Curator] helped to focus my strong opinions in a way that’s impactful.

We talk often today about the redefinition of fashion, art and design. What does “to redefine” mean to you within each of these fields in both today’s Western society and within the context of globalisation?

To me all of these worlds intersect and overlap, and provide inspiration for each other – before there were designers there were artists. Artists are designing in their own sense, and designers are creating works of art through their work. We need to stop categorising something as one or the other.

How do you see fashion as a vehicle to explore identity?

I think fashion is a vehicle in different ways for different people.

As a curator I bring together visual artists, graphic designers, musicians, architects, fashion designers and photographers, then I prod them in a certain way, inspire them, show them things and ask them to collaborate to see what comes out. Do you see yourself in a similar role? If so, how was this exhibition a different format from your usual practice?

I guess you could say it’s similar. It sort of woke me up to the importance of organising my work in a way that the museum world could understand my practice; but also that a younger generation could see how vital a museum space is to think and experience outside of their phone.

If every visitor was to walk away from the exhibition with just one firmed up thought what would you love this to be?

My optimistic hope is that this can be a cool alternative to more dangerous lifestyle choices people sometimes make. I want people to see themselves in this exhibition and in this museum. I’m offering a different surface area for both me and them to interact, beyond just buying a ticket and looking at some stuff.

Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech” is open until 22nd September 2019.