A beginner’s guide to outsider art

Raw Vision magazine has been showcasing unknown, self-taught and visionary artists for more than three decades. As the publication turns 35, founder John Maizels and interviewer Artemis van Dorssen introduce us to the hidden glories of seven artists living and creating around London today.

Culture

Photography: Maxwell Granger

Words: John Maizels

Interviews: Artemis van Dorssen

Taken from the spring 24 print issue of THE FACE. Get your copy here.

The first inkling that there may be “another” art out there – an art unaffected by teaching or convention – emerged from the work of a few inspired psychiatrists in the early 20th century. They observed that inmates at the newly built asylums that had sprung up across Europe and North America were obsessively drawing on scraps of paper and hiding them in their clothes to prevent staff from sweeping them away at the end of the day.

These works – by people who were, at the time, considered to be the lowest of the low in society – were initially collected as specimens, objects of study to help analyse psychiatric conditions. It was Dr Hans Prinzhorn of Heidelberg Psychiatric Clinic in Germany who carried out the first serious study of patients’ creations and recognised their work as art with the publication of Artistry of the Mentally Ill in 1922. Modern artists of the day such as Paul Klee, Hans Marc and other Germany-based expressionists became big supporters and followers of Prinzhorn’s discoveries, reinforced by surrealists such as André Breton and French painter Jean Dubuffet, who had a copy of Prinzhorn’s well-illustrated book.

Dubuffet formulated his theory of art brut in 1948, having realised that spontaneous expression came from many sources, not just those with mental health conditions. To him, art brut meant “raw art”. Raw because it was “uncooked” by culture, unaffected by any artistic or cultural influence. Dubuffet saw how the artists worked from inner compulsion, not for fame or fortune, oblivious to the need of an audience or for “success”. It was a force within them that was so strong their emotions had to be expressed. They did not so much reflect the world around them but the world within.

The French artist built up the world’s biggest collection of art brut, including works by mediums, visionaries, fierce independents and eccentrics, as well as examples from the mental-health institutions of Western Europe. These artists worked with their chosen materials, often using what happened to be on hand, such as mud, house paint, beer cans, stones, broken crockery and all manner of recycled items. His collection was eventually opened as a museum in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1976.

English writer and poet Roger Cardinal was one of the first academics to study Dubuffet’s theories and collection, and in 1972 published the first book in English on the subject. He wanted to call the book Art Brut, but the publishers insisted on an Anglicised title, Outsider Art, which eventually gave a name and identity to a range of creations. From those early days – when outsider art was unknown, even secret – it has grown into an accepted phenomenon where artists without training or background can be valued. Some even claim the automatic drawing and pure psychic flow of creativity, one of the hallmarks of outsider art, makes it the purest form of art yet discovered.

There has been much criticism of the term “outsider art”. In Europe, art brut is often preferred, while in the US “self taught” is seen as less pejorative and judgemental. Because while they may be outside the normal art world, as time goes on there is increasing acceptance: many contemporary professional artists find (rarely acknowledged) inspiration in their work, while there are dedicated museums, or specialised departments within them, that showcase outsider art all over the world.

“[Outsider art] It is an international phenomenon and we can only hope that one day there will be permanent locations in Britain where it can be more widely appreciated and respected”

Women and people of colour have a large presence in the international field of outsider art, especially in the US, where Black self-taught artists from the South have had a unique impact. But while the most celebrated English outsider artist, mediumistic housewife Madge Gill, would be honoured with a dedicated museum in most countries, here her work is stored away, even though it was all donated to her local London borough, Newham. There is not a single work of hers at Tate Britain, not even in storage, although there are large holdings of her huge drawings in museums in the US and Europe.

In Britain, those who would be considered outsider artists have a difficult time getting through its elitist art world to the public, and galleries that show their work are few and far between. Brighton-based organisation Outside In has been successful in supporting those who are separated in some way from the conventional art world, providing an online platform that showcases their work. There are various studios, too, that have been set up to help give some creative stability to unknown, self-taught artists’ spaces, such as Barrington Farm in Norfolk and Project Ability in Glasgow.

Britain is also the home of Raw Vision, still the world’s only international publication of outsider art. Over the years, we have introduced hundreds of unknown self-taught and visionary artists to an ever-growing audience. This international approach has resulted in the documentation of artists around the world. Nek Chand’s Rock Garden in Chandigarh, India, for example, contains more than 2,000 sculptures made from cement and waste materials, spread over a 25-acre landscaped area that includes waterfalls and amphitheatres.

Outsider artists working today are rarely the complete isolates that Dubuffet studied. It is almost impossible to be as insulated from the effects of modern culture as those early discoveries. This art will only grow in importance. It is an international phenomenon and we can only hope that one day there will be permanent locations in Britain where it can be more widely appreciated and respected.

Despite the difficult climate in Britain’s art world, there are many outsider artists quietly at work around the country. They do not need an audience or fame – they work only for themselves. John Maizels

Sue Kreitzman

Sue Kreitzman went from being a food writer in New York to creating feminist art from her home in East London. What changed? “I figured either the muse bit me in the bum, or I had a psychotic break – or more likely it was the menopause,” says the 80-year-old, laughing. “My hand picked up a marker and drew a mermaid on a piece of scrap paper. I looked at her. She looked at me. She took over my life. I never wrote another cookbook.”

Now, Kreitzman paints with nail varnish or acrylic on paper and found wood, often collaging buttons, toys and jewellery on top. It’s all on display in her home, with images of heroines and goddesses smothering the walls, peering out from behind deconstructed mannequins wearing jewellery. “I’m only interested in the female landscape,” she says, gazing at a mannequin with little alarm clocks at the ends of her nipples. “I love men, I’m married to a man, I have a son. But I’m not interested in men as far as their inner life or their spirituality.”

That’s also why Kreitzman has painted her walls red, matching her glasses, clothes, carpet, furniture and much of her artwork. “It’s because we bleed every month. It’s the colour of blood, it’s a feminine colour.” Plus, red is the polar opposite to Kreitzman’s biggest fear. “I’m scared of beige the way some people are scared of heights. It leeches the life right out of you.”

Kate Bradbury

Characters with paintbrushes for hands and suitcases for bodies populate Kate Bradbury’s studio in Stoke Newington, Northeast London. “I am attracted to found objects by their history, texture, pattern, shape and colour to make a new story out of them, to repurpose them,” says the 63-year-old artist, who’s also part of folk band Diego Brown and the Good Fairy.

When she’s not creating theatrical sculptures or making music, Bradbury works on hyper-detailed ink drawings that often incorporate sycamore leaves or words she finds inspiring. “Because I use a very fine pen when I’m drawing, the line can almost be like the line of the script rather than a drawing, a sketch or a pattern. It can become a word which is as much of a pattern as the design.”

She listens to music while she works on her hypnotic pieces, repeating words as she draws, almost like an invocation. “It’s the repetition, the fractals, the sort of pattern where it’s flat on the paper, but actually when you look at it, it becomes three-dimensional,” she says. “You can make a ‘world’ where it looks as if you’re looking into a stage or a portal just by putting flat lines on a page.”

Ben Wilson

Instead of white gallery walls, Ben Wilson’s creations are stuck to the streets of London. Known as “the chewing gum man”, he’s been creating miniature paintings on discarded bits of gum for the past two decades, mainly around the Millennium Bridge over the River Thames, which he’s been working on since 2013. “People will say I spent my time changing rubbish into art,” he says. “I’ve created a thing that worked with [the litter] rather than getting upset about it. I’ve tried to find a creative solution to the problem.”

The 61-year-old often dedicates the chewing gum paintings to passers-by, and he always has a thick wad of notebooks full of requests besides him – so far, he’s painted everything from fry-ups to self-portraits. When the City Bridge Foundation, a charity which maintains some of London’s bridges, set out in October 2023 to “clean” the Millennium Bridge and remove Wilson’s paintings, he took them to court. “I had to say: ‘You can’t just destroy this because it’s art. The gum has been transformed!’”

Wilson also makes large-scale sculptural gardens out of wood, monochrome tiles and canvas paintings. But his chewing gum art is what he’s best known for. Each piece takes days to finish, as he turns blobs of gum into artworks that reflect the communities he meets while he works in the street. “A fundamental thing that I’m totally opposed to is that people are out of touch with their environment. That’s why I take the very thing that has been spat out and thrown away, which is a product of consumerism,” he says. “Chewing gum by its nature is artificial. There can’t be a better thing to try and change.”

Carlo Keshishian

Former NTS Radio host Carlo Keshishian’s work is heavily influenced by his background in music, having spent years broadcasting obscure jazz from the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s on the Sees to Exist show. “If I’m drawing and playing music at the same time, the rhythm, the pace or the intensity [of the songs] affect the quality of the line I’m drawing with,” says the Brixton artist. “My mood affects the drawing.”

Working with pen and ink, the 43-year-old draws hypnotic patterns and spirals, weaving tiny, indecipherable confessions into the gaps. They’re dubbed “diary drawings”, so it’s unsurprising that Keshishian has been told that he’s “hiding in plain sight”. His instinct for linework first became apparent at school, where his teachers would give him extra paper so that he could doodle as an outlet. “I was drawing on my schoolwork, lots of lines and little characters and things. Then I started putting a few words in it here and there. Now it’s only words.”

Raymond Morris

From a painting framed with Oxo cubes to miniature, gold, spray-painted horses that climb the walls, Raymond Morris’s flat in Cricklewood, Northwest London is an extension of himself. He paints on his radiator and writes concrete poetry, which incorporates graphics into the words, on every available surface.

“I’m an extractor, I produce an idea through the line,” says the 72-year-old, pointing at layers of paint that have caked a canvas to the wall in his flat. Morris’s work is deeply spiritual, and he credits for inspiration the entities that he views as working alongside him. “The spirit of God came upon me some time ago and filled my head up with wonder and told me what to do, and I did it.”

Because of this, Morris produces his art through raw improvisation, letting the words and shapes come to him, with the help of Vivian, his guide within. “I don’t say what I’m going to do. I just do it, like a child, so it’s intuitive,” he says. “My approach to work is never pre-planned. Never. It’s authentic.”

Stephen Wright

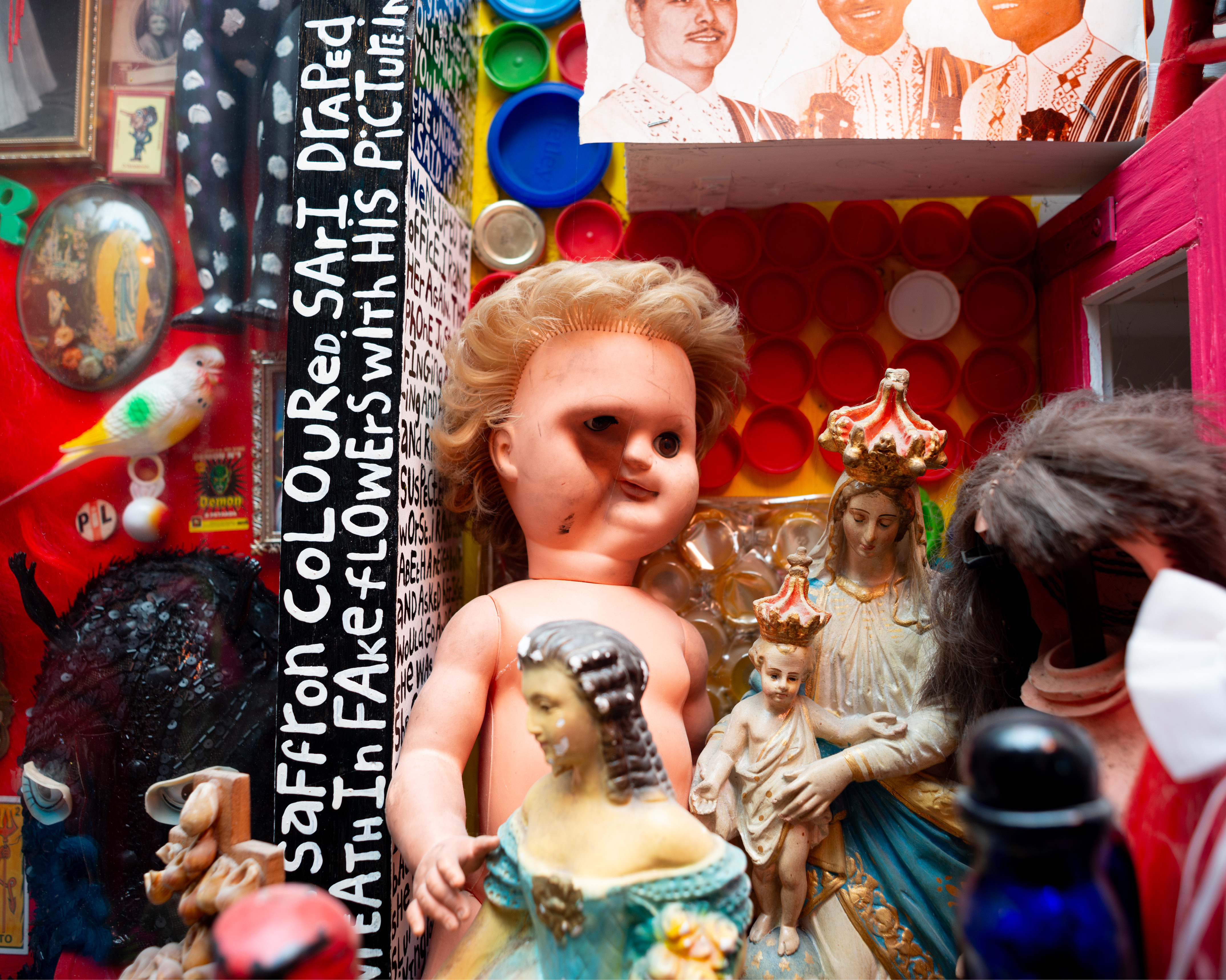

At least a dozen dolls blink at you as you approach Stephen Wright’s front door, legs akimbo and hair enmeshed with garden foliage. The former head stylist at Elle Decoration and knitwear designer lives in a flat above the museum he created in a three-bedroom Victorian house in Southeast London.

Wright’s House of Dreams is a sort of lived-in diary of his life, interwoven with floor-to-ceiling mosaics, mannequins, dolls and found objects. “I make a living out of me, which I always have done,” says the 67-year-old artist, who travels all over the world to hunt for objects to fill his museum. Materials brought back from a recent trip to Mexico include an unholy combination of gimp masks and postcards of the Virgin Mary.

Wright started House of Dreams with his late partner Donald, who passed away within a year of Wright’s parents 20 years ago. For perhaps not unrelated reasons, he is particularly interested in collecting broken dolls. “It’s about making a family,” he says, pointing at three newly acquired members. “But they’re not perfect in any way. The eyes don’t work. Or they have a skin condition. Or the leg’s fallen off and nobody wants it. Well, I do.”

Wright is so invested in preserving the lives of discarded objects that he doesn’t even wash the items that come into his house. “In a flea market in Paris, I bought 88 rubber dollies with no heads, covered in pigeon shit. They’re all hanging downstairs with pigeon shit on them. And because it’s French pigeon shit, it’s more exotic.”

Nick Blinko

An anarcho-punk spirit runs through all of Nick Blinko’s work, from bands The Magits and Rudimentary Peni to his hyper-detailed illustrations. The 62-year-old uses pen and ink to create drawings of dystopian scenarios, carving out the details with minuscule cross-hatching, and has designed album covers for his cult musical outfits.

“Black and white is more spiritual because colour appeals to the senses,” says Hertfordshire-based Blinko of his colour palette of choice. The horror elements of his drawings, meanwhile, are “a hangover” from his experience of being diagnosed at 17 with schizoaffective disorder.

For now, though, Blinko has substituted music and drawing to create knit and textile works, with the proceeds of his sales going to Saint Francis Hospice in Essex. “I think, unfortunately with punk, the loudness has led, particularly with men, to a kind of depression and self-destructiveness,” he explains of his pivot. “It crushes things, it’s so relentlessly stomping.” But he’s still found a way to incorporate his punk days into his new discipline: an owl-shaped pin cushion, bearing the slogan “I eat Magits”.