Closed Hands: the novel-sized game exploring extremism

Directed by Dan Hett, Closed Hands examines the causes and effects of a terrorist attack in a fictional UK city. It’s inspired by the experience of losing his own brother, Martyn, during the Manchester Arena bombing in 2017.

At the centre of the screen is a text box that simply reads: “Incident”.

What kind of incident, we’re not told precisely. For Dan Hett, director of interactive fiction game Closed Hands, it’s quite deliberate and irrelevant: “All we need to know is that something happened, and there were reasons for it, and there were effects afterwards.”

The incident is actually a terrorist attack, which occurs in the fictional UK city of Hartwich. From a personal perspective, it’s understandable why Hett has no interest in depicting the attack itself in gratuitous detail. In May 2017, his brother Martyn, 29, was a victim of the Manchester Arena bombing that killed 23 people.

But if Closed Hands isn’t about the attack itself, it’s also not about Hett either. Indeed, the 35-year-old from Stockport had already channelled his grief by making a trilogy of experimental games, available for free on itch. And as an outspoken anti-fascist campaigner, as well as a co-founder of Survivors Against Terror – whose members include Brendan Cox, widower of the Labour MP Jo Cox, who was murdered by a far-right extremist in 2016 – Hett was already conscious of the wider societal issues that underly any act of extremism – on both ends.

“There’s a lot of dialogue around this that’s much bigger than me,” he explains. “When I went through everything, I became one part of this enormous story made up of hundreds of people that were suddenly connected by this single event. I’ve met hundreds of people that I should never have met and had no reason to meet, other than us being linked by the atrocity.”

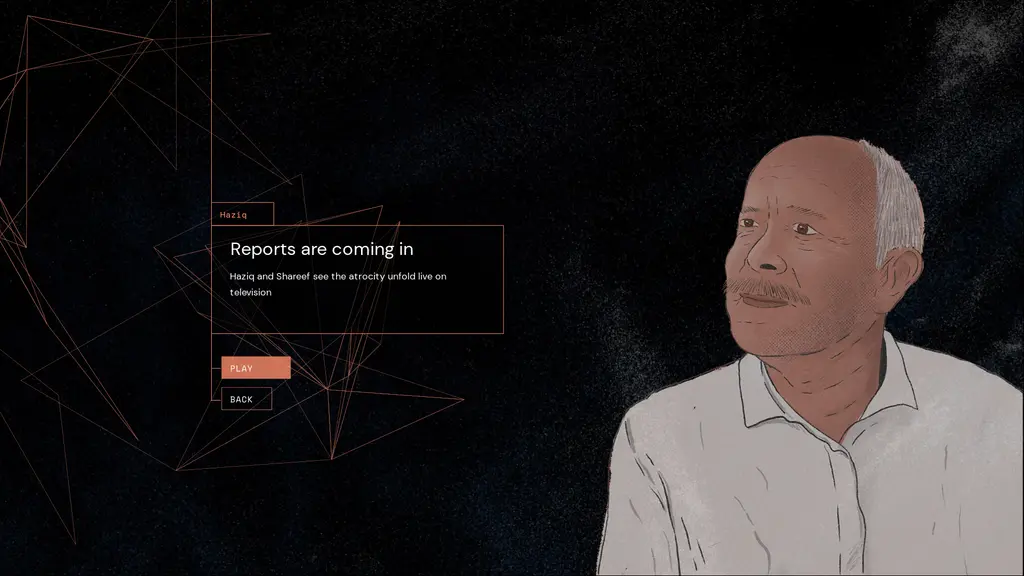

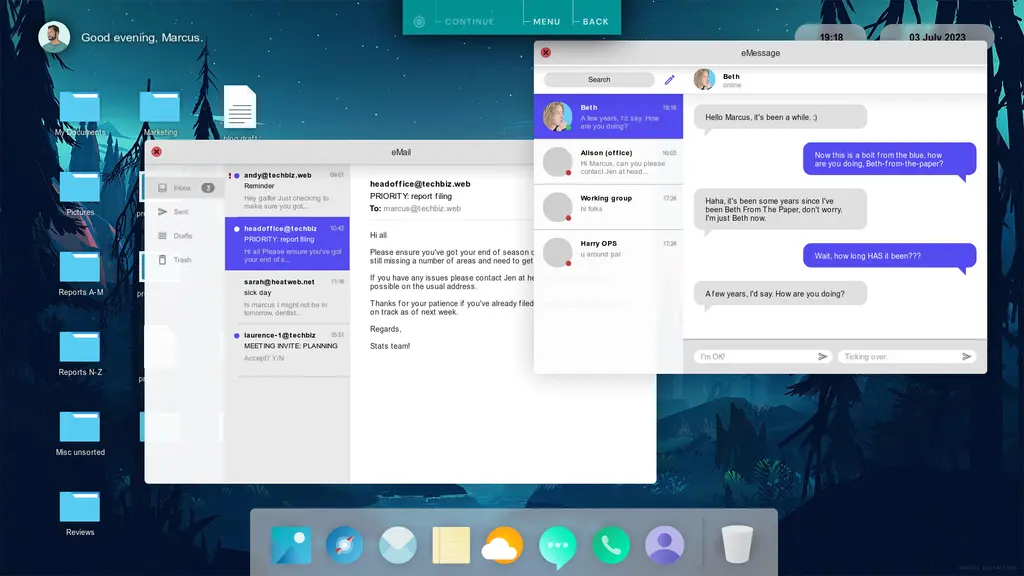

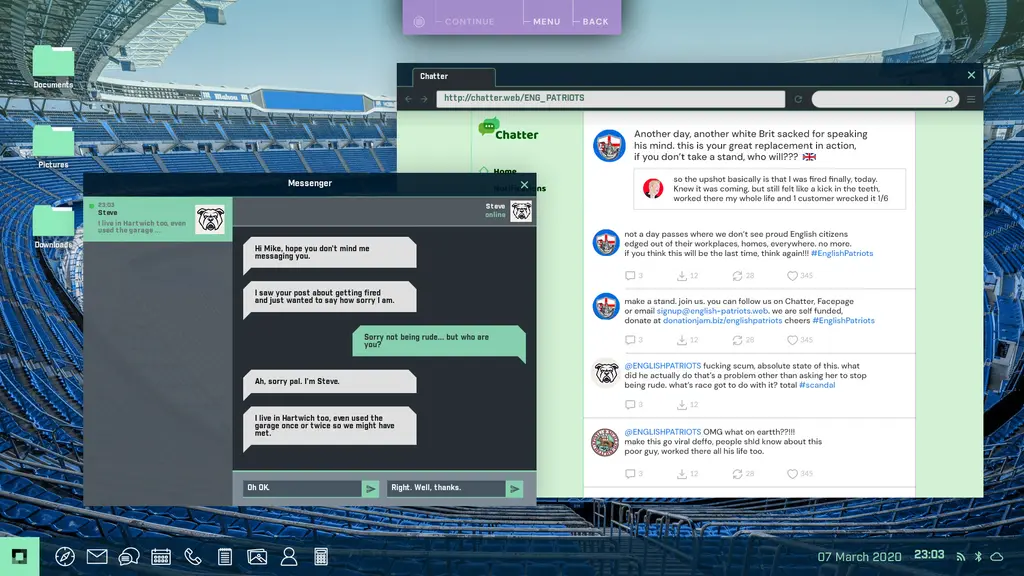

Closed Hands explores this idea by “pulling the camera back” to examine the lives of five people: Marcus, a young man caught up in the incident indirectly as a witness; Beth, a local journalist pursuing the story; Farrah, an intelligence operative who tracks and acts on extremist intelligence; Haziq, a Muslim business owner who’s the father of one of the attackers; and Mike, a lifelong Hartwich resident who’s gradually been pulled into a far-right group.

These characters literally surround this incident at the start of the game, as the player follows one perspective and then another, each time opening up a node that leads to a new path like a branching, intertwining web that takes them back in time and into the future.

As a piece of interactive fiction – a niche genre better known for personal and experimental work, including Hett’s own c ya laterrr – Closed Hands is ambitious and complex, with an estimated word count of 130,000 words that rivals a novel.

Which begs the question: why not just write a book then?

“It would have been literally easier to just sit and write a novel – at least they go in a straight line,” Hett laughs, before clarifying that the word count includes all the scenes in the game, including multiple paths, as well as dozens of “extras”, which provide one-off perspectives from minor characters. It’s a game that can be fully experienced in a few hours, though how much they want to delve into each of the nodes linking each character and scene is also left up to the player.

“We designed it so that a player would still have a meaningful experience if they chose one character and went through it linearly, whereas some of our playtesters have kind of dotted around and gone to absolutely every single thing,” he continues.

“We’ve been able to design and write it in a very fragmented style. A player can shoot 20 years into the past with one character, and they won’t look at the incident for another 10 scenes, while another will go in both directions, while some will only go into the future. You wouldn’t be able to facilitate that in a novel.”

DAN HETT

Besides the scale of the project, Hett was acutely aware that in order to depict the diverse cast, he wouldn’t be able to make Closed Hands himself. That’s why he formed remote studio Passenger, where he collaborated with a team of writers, including comics writer Umar Ditta and Sharan Dhaliwal, editor of South Asian lifestyle magazine Burnt Roti.

“It was very important that there were multiple voices, as there are scenes, such as with the Muslim father, that I’m just not equipped to write. There would have been no authenticity from me. So I went to people like Sharan and Umar, who were able to come on board and shape those things for me in a way that I never would have done.”

There were also challenges with depicting some less sympathetic characters, notably Mike (“so diametrically opposed to everything” Hett or any of the team stand for) and Beth. The news reporter is conflicted between getting the story and the ethical quandaries that throws up – something of which Hett had direct experience after his brother’s death, and also the subject of his microgame Sorry To Bother You.

But in researching Beth’s character, he was able to turn the tables around.

“I dug up my DMs from 2017 and went: ‘Actually, can I ask you some questions now?’” he recalls with a smile, explaining that he used this method to speak to multiple journalists to understand the difficult positions in which their work puts them. “Beth emerged from that, in the way that we didn’t want any of these characters to be exaggerated tropes.”

Far from stock characters, we see these people as human beings with all their complex histories extenuating circumstances. That extends to Mike, a far-right figure who could have become a caricature easy to hate. But by exploring deep into his timeline, we’re able to witness the normalised racist attitudes he was brought up with, as well as the circumstances that made him vulnerable to radicalisation.

It’s through these characters that players can grapple with more complex and challenging issues than either a sensationalised blockbuster or even an adventure game with puzzle-solving win states. Players of those kinds of games might not gravitate to an experimental text-based game, though acclaimed indie releases of recent years like If Found… and Bury Me, My Love prove such an audience does exist.

For Hett, however, it’s also the perfect format to convert a non-traditional gaming audience, such as HOME Manchester’s Push Festival, where Closed Hands will be launching in March.

“The arts crowd, for want of a better term, may already be interacting with cinema or theatre that tells difficult stories, but they have no idea that video games are also telling complex, meaningful stories,” he says. “They’re also worried you may need to learn how to use a controller or that they wouldn’t know how to install it. So we’ve used text and computer interfaces to remove those barriers.”

Capturing the interest of an “untapped” audience has certainly been enough to convince Arts Council England, who have fully funded Closed Hands’ development, a first for anything of its scale. This has afforded the team both a budget to produce a polished premium work, featuring illustrations fromLoz Ives and ambient music fromCiaran McAuley (RUMA)andPaul Wolinski (65daysofstatic), that’s available for free.

Hett hopes that this won’t just incentivise more people to discover the game – or games in general – but also open the door for more Arts Council-funded games, which remains a vastly underexplored territory. Failing that, at worst, everyone at Passenger has already been paid, and an ambitious, thought-provoking title still exists in the public domain.

“Rather than 100,000 people playing it on Steam, I’d rather 1,000 people play it, really fucking understand it, and it lands,” Dan Hett says. “It’s a unique position to be in, but I quite like it. It’s a piece of work that we’re proud of.”

Closed Hands is out now