The pandemic digitised culture, can it democratise the arts?

From Fortnite exhibitions to virtual museums, the art world is innovating online. It’s a change of pace that’s bringing in swaths of new audiences.

Culture

Words: Martin Guttridge-Hewitt

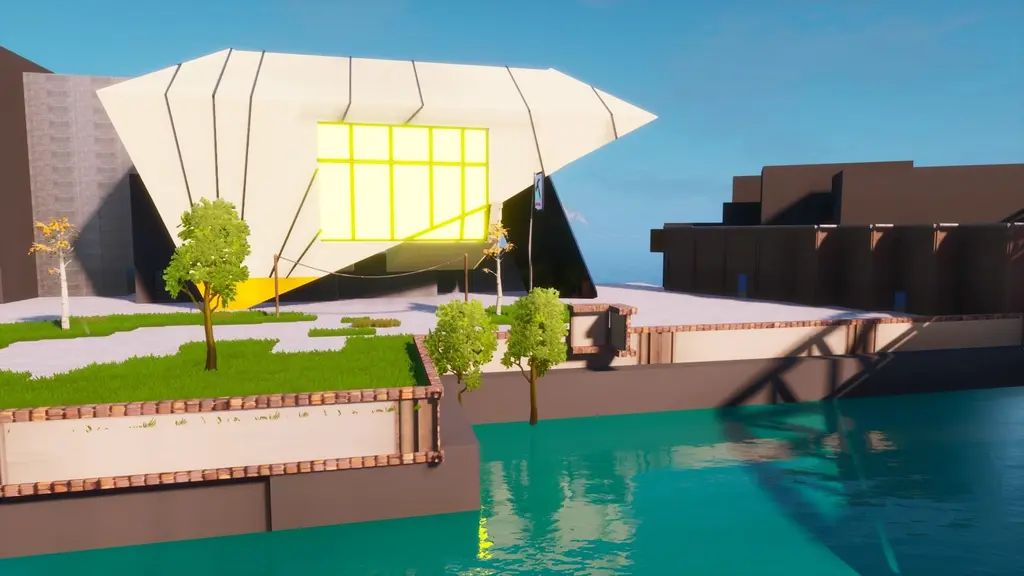

When The Factory opens next year as a permanent home for the biennial Manchester International Festival (MIF), an estimated 850,000 people will see its interdisciplinary arts shows annually. Virtual Factory, a replica venue inside gaming platform Fortnite, welcomed over one million in July 2020 alone.

“We realised that there are loads of people who we were not aware of, who we’re not engaging,” says Gaby Jenks, MIF’s Digital Director, of how the experimental project quickly garnered massive uptake among the game’s established community. “But I don’t want to go down that really boring narrative of how we can reach a global audience.”

Her position is valid. Last year, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, culture nosedived into the digital world, driven by fear of invisibility. Efforts were often rushed and reductive, such as canvases converted into JPEGs or simple live streams. Virtual Factory began with a different brief: build a new type of space and ask who wants it.

The process found hidden art audiences in gamers who became contributors to a wider piece. Your Progress Will Be Saved by digital avatar artist Le Turbo Avedon is a 3D platform with egg hunt elements, in which challenges are completed to uncover new parts of a narrative.

The “close-yet-far tension of being alone online, together” is confronted by a journey through shifting environments within Virtual Factory. A demographic the institution hadn’t previously engaged – Fortnite players – became enthusiastic collaborators the moment they entered. Each of their interactions altered the original artwork, because it’s a responsive game.

The UK government’s Taking Part survey shows only 51 per cent of adults visited museums and galleries between April 2019 and March 2020, showing just how many people were disengaged with the arts before the pandemic. Digital clearly has potential to increase that engagement and it goes beyond overcoming geographical distance. A paradigm shift is taking culture into mixed realities, where countless coded environments can be designed by and for innumerable communities.

“You can see the application of how these things might slowly evolve. There’s going to be a convergence of evolution in research and design,” says Jenks, nodding to development in robotics, XR, mobile and blockchain. “That means there’s probably quite an explosion coming in terms of capacity and ability to make really exciting experiences from a cultural perspective.

“I feel like a cultural venue should be an enabler, a curator and an experimenter in that space,” she continues. While much of what she currently sees in the sphere is digital for digital’s sake, she asserts that a “collapse of barriers between culture IRL and URL” is happening.

“We need to focus on understanding how we deliver content that exists across different platforms and what this means for everything underpinning that. How we commission people, how we attract people, all of those sorts of changes. I think the most exciting space right now is where people are developing their own tools and communities, and building on that.”

Following that model, London nightclub FOLD established Futur Shock to make sense of our acceleration into digital culture after dancefloors closed last year. Founder Karolina Magnusson Murray explains how the artist-led organisation came up with the idea through a need to reflect and understand relationships with a virtual world undergoing exponential growth.

“It’s essentially a multi-disciplinary platform that brings together electronic music, sound, art and digital culture into, what I would say is, a more a democratic space,” she says. Online learning is also a focus of Futur. Shock, equipping others with creative digital skills. Later this year, an exhibition is planned inside both the brick and mortar FOLD and a virtual environment that doesn’t exist yet, while a separate project has the team building a digital version of the real-world venue.

The Factory in Fortnite Creative

Virtual Factory exterior

“This was something we thought about quite a long time ago, at the beginning of the pandemic, but with exhibitions and everything popping up online, we didn’t really want to contribute to that part, because it’s supposed to be about this feeling of emptiness,” Magnusson Murray says.

Instead, the concept will see guests navigate a desolate digital club with sound installations. “It’s a place for our predominately queer community. In a way, we developed it as a protest against the idea we have no safe space for our community, there’s no place for us to congregate.”

“I think the most important part [of digital] is that, actually, it’s now more a space where you can give power to under-represented communities, who wouldn’t necessarily be able to show their work in major galleries or even get it into any space where it could be seen,” she continues, referencing New Art City, an online gallery offering virtual exhibition space within a 3D platform.

“It gives the opportunity for small scale galleries to have huge footfalls and for people to engage with these emerging artists that mainly make digital work as well. Spaces like that are really important and I think they’re only going to develop. This is, I suppose, the beginning stages of it.”

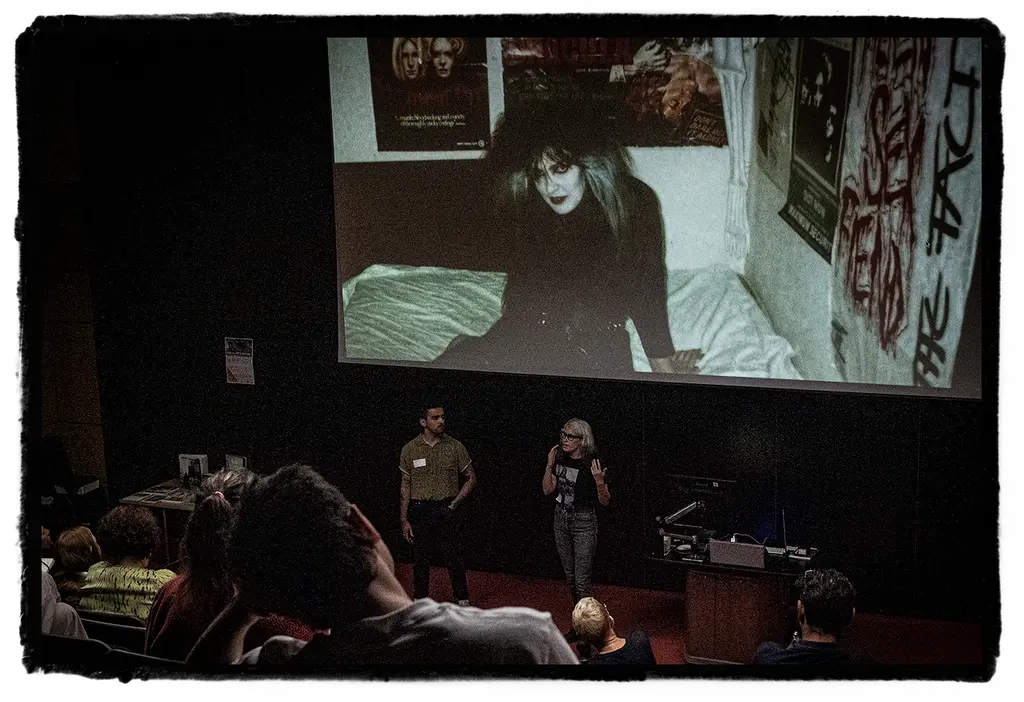

The Museum of Youth Culture is having similar conversations around tech empowerment. Starting life as a photography archive born from Sleazenation magazine, an exhibition at London’s Southbank Centre six years ago meant the vast collection needed curation for the first time. Gaps in the timeline were glaring, so an open digital submission system was established, allowing anyone to contribute images and information to help represent their community more accurately.

The institution exists online, but long-term plans entail real-world sites across the UK, each representing the surrounding region. Digitising culture is not only making art more accessible online, it’s also making physical galleries more democratic.

Museum of Youth Culture

Museum of Youth Culture

“We had loads of images of gay nights, drag queens and things like that. But we didn’t really have a queer perspective from the people who were involved and actually there,” Museum of Youth Culture’s Jamie Brett says. Paradoxically, the list of content that the museum was lacking also includes “mainstream culture”, because documentary photography often favours the niche.

“We started with the idea that this tells everybody’s story,” he says. “I think we’re trying to make sure that we’re covering every single area from the horse’s mouth, rather than trying to curate something and pretend we know it,” Brett comments on the overall ambition. “There’s a lot of arrogance. A lot of the time with youth culture scenes either people think they know what they know, or what they did, but was it bigger? There’s always something hidden behind it.”

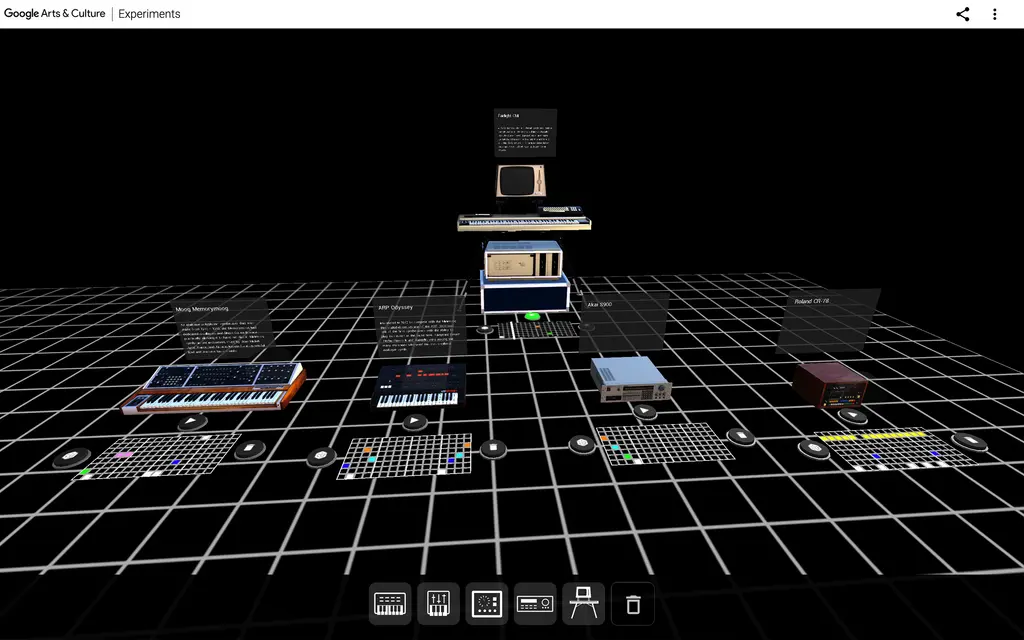

In March, the organisation partnered with Google Arts & Culture for Music, Makers & Machines, an online and app-based deep dive into electronic music, rave, and club scenes. Through gamification, essays, and geotagged tours of lost clubs juxtaposed with archive footage, it tells a complex series of interlinked stories well beyond anything physical spaces could convey.

Brett’s team was involved in a number of aspects, including digitising data from 17,000 printed event flyers owned by Phat Media, now searchable for any user who attended those parties, and everyone else who didn’t. The process needed bespoke technology, which Google Arts & Culture was established to pioneer. The tech giant’s educational initiative was conceived to offer a platform and solutions to cultural organisations worldwide, who take the lead on content. Together they realise ideas that can grow audiences, creating a library of free tools in the process.

“Google Art Camera is [another product] we’ve been developing over the course of many years, it’s a very special camera that, in about 30 minutes, allows you to capture one square metre of artwork in gigapixel format. Billions of pixels,” says Luisella Mazza, Head of Global Operations at Google Arts & Culture. The portable device has a more powerful sibling, which aided the discovery of never-before-seen details in Marc Chegall’s 2400-square-foot frescoes adorning Paris’ Opéra Garnier ceiling.

“This gives you a sense of how technology, together with the ambition and the enthusiasm of our partners, a great eye for detail and passionate people can find incredible things that would otherwise never be possible. This is one example of the doors digitisation of culture opens,” she says. Over ten years, Google Arts & Culture has collaborated with around 2,500 museums and galleries.

Technology has its own inclusivity and accessibility issues, from those who can’t code to the near‑3.7billion without internet access. Digital biases, inequalities and prejudices often mirror reality, and these must be overcome before the sphere can truly succeed in democratising arts and culture.

But the potential is clear. As Gaby Jenks explains, to make democratisation happen, organisations must continue experimenting in a bid to help us all understand, participate in and benefit from the mixed reality journey:

“We should be looking at this and figuring out not only how we can engage with it, but also how we can develop new narratives around it. It’s not just about global reach, but about questions around sustainability. What does this really mean for our planet and people?”