The Power (Station) of Art

Make the humble, post-industrial German town of Luckenwalde your new contemporary art destination.

Culture

Words: Benoît Loiseau

Photography: Lukas Korschan

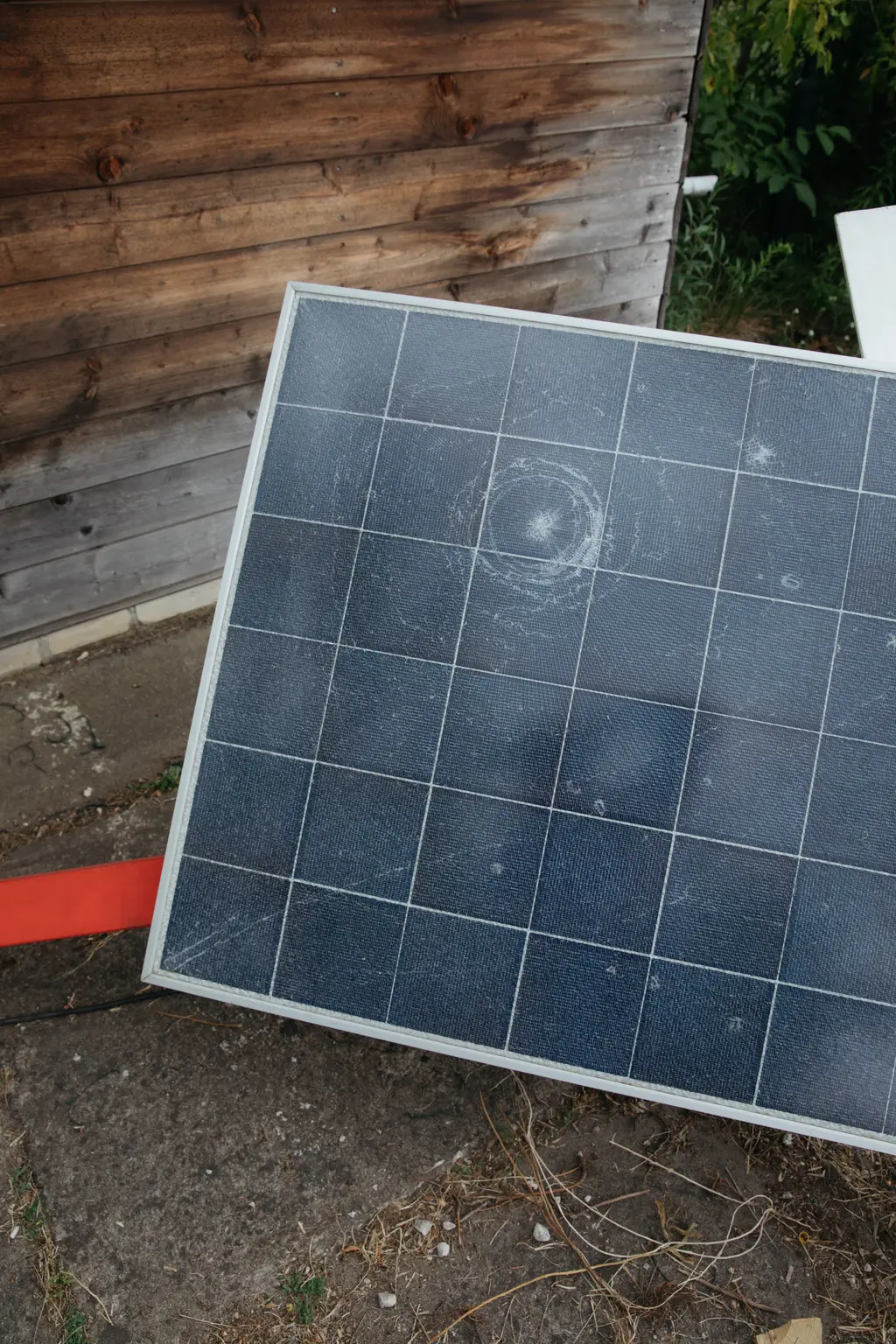

If you haven’t heard of kunstrom, it’s time to get with the programme. “Art electricity” (translated from the German) might power your house sooner than you think. Kunstrom incorporates green technology, from wind sculptures to solar panel-based performances and guerilla-style hijacking of electricity supply points to produce electricity that can be monetised and fed back into the national grid. It’s an artistic method that reveals the process of its own production. It’s a full-circle, utopian model in the age of climate change. And thanks to E‑WERK, it’s now a reality.

This freshly-opened sustainable arts centre and energy provider has set up camp at a former coal power station in the humble town of Luckenwalde, 30 miles south of Berlin. Dating from 1913, the listed building (which features elements of art deco and art nouveau) spans four floors and 10,000 square metres of workshops, three exhibition spaces and eight artists studios. It now joins the ranks of post-industrial art meccas à la Tate Modern, Dia: Beacon or Hamburger Bahnhof (all housed in similarly converted buildings from factories to tram depots), only E‑WERK remains loyal to its original purpose.

“I thought a lot about autonomous ways of producing art that aren’t dictated by the market,” says founder Pablo Wendel, as he shows me around the vast industrial space which he acquired in 2017 under his non-profit organisation, Performance Electrics. It was while living precariously off irregular grants and in rundown studio spaces across Stuttgart that the RCA graduate, now 38, started to experiment with energy. “I started to produce electricity with art,” says the German artist-cum-energy provider.

Now with E‑WERK, kunstrom has its own permanent home. As part of its launch, a quarter of the old power station was reactivated for the first time since the collapse of the Soviet Union (with the guidance of supportive former factory workers), creating 40 kilowatts an hour — enough to power the arts centre and up to 200 homes. “It’s a critique of power,” comments joint artistic director Helen Turner, Wendel’s work and life partner and the former head curator at Chichester’s Cass Foundation. “As a utopian and autonomous place, it completes the circle,” she says, pointing to the centre’s combination of production, exhibitions and live/work spaces.

The sustainable art hub opened this month with a solo exhibition of radiators sculptures by French artist Nicholas Deshayes, an outdoor flags commission by the Brit Lucy Joyce, an architectural pavilion by German studio umschichten and a performance series in collaboration with the London-based organisation Block Universe. With its dynamic programme, E‑WERK is set to lead the cultural revival of Luckenwalde, an otherwise-understated industrial suburb which, surprisingly, is home to some 150 listed buildings, including a derelict Bauhaus swimming pool and a former hat factory designed by expressionist architect Erich Mendelsohn.

“As rents continue to skyrocket in Berlin, E‑WERK’s affordable studio spaces provide a timely alternative for priced-out artists.”

Considered Europe’s ultimate artists paradise since the fall of the wall, “poor but sexy” Berlin is now on the verge of becoming yet another gentrification horror story. As real-estate prices continue to skyrocket (up to 20.5% in 2017, then the fastest growing in the world), artists communities are increasingly vacating trendy areas like Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain to make way for start-ups and corporate offices. Now a 40-min train ride away, E‑WERK’s affordable studio spaces (twice as cheap as in the capital) may well provide a timely alternative for priced-out artists. “It creates a sense of community,” says Turner of the rolling scheme, whose rents help fund the exhibition programme. “It’s a good economic model: everybody wins.”

Pablo Wendel and Helen Turner

While we’re far from seeing the effects of urban gentrification spreading to this former East German town (its population, shy of 20,000, has been in near-constant decline since the reunification of the country), the team at E‑WERK is conscious of their impact on the locality and its population. “The worst thing would be to become an international contemporary art island,” says Turner, who leads the community-outreach programme. “I really want to try and make it as accessible as possible,” she continues, “but I also don’t want to dilute the programme, I don’t want it to not be challenging.”

So can kunstrom change the world? In a way, it already has. Art has the power to project realities we couldn’t have otherwise imagined. Or as Wendel says, “You see the world how you want to see it, and how you want to change it.” As for Luckenwalde and its inhabitants, whose world once revolved around the power plant, the future will tell whether they’re prepared to see it change too.