Inside the mystery of Kowloon’s Walled City

Children playing on walled city rooftop Hong Kong 1989, courtesy of Blue Lotus Gallery

Amongst the day-to-day prostitution, gambling and smells of rotting carcasses, Greg Girard set about capturing the final decade of the vice-ridden city in the heart of Hong Kong.

Culture

Words: TJ Sidhu

Photography: Greg Girard

When photographer Greg Girard (@gregforaday) visited Hong Kong in the mid-70s, he’d heard of a mysterious community set in the heart of the country, where prostitutes and priests lived side-by-side, and drug addicts and children walked the same halls. He’d never seen pictures, nor did he know anyone who had visited.

“In 1985, I simply stumbled across it one evening. I came around a corner and there at the end of the block it loomed: this massive building-thing that looked like nothing else I’d ever seen. ‘This must be the Kowloon Walled City’ I remember thinking to myself,” Girard tells me.

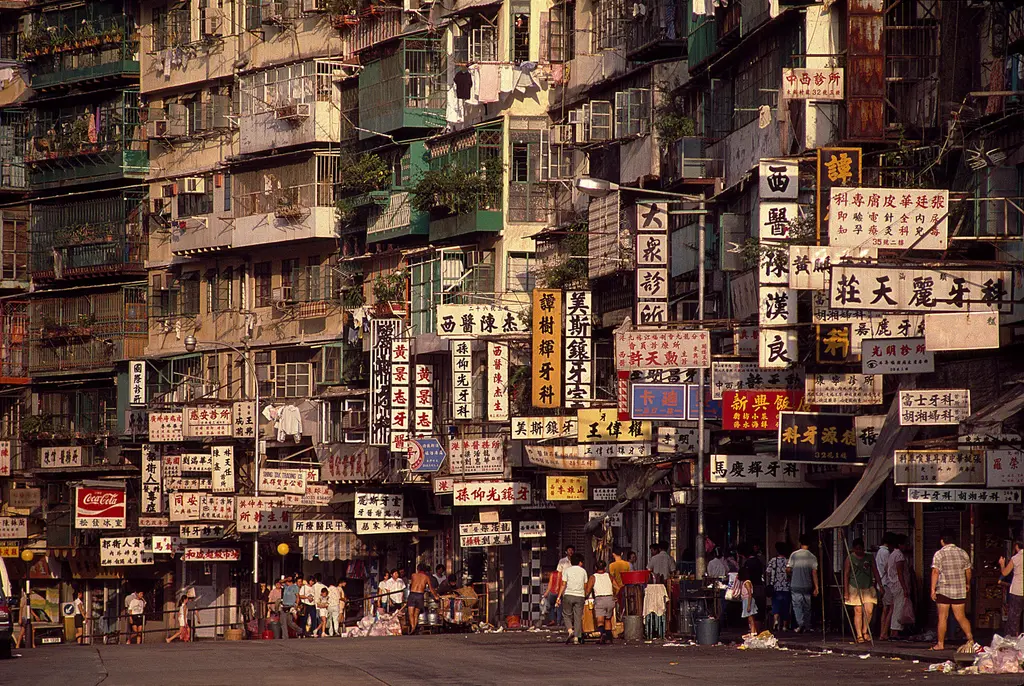

The Kowloon Walled City, with a history tracing back to the Song Dynasty (960‑1279), was an entirely self-governed city within Hong Kong – a closed-off complex of extreme poverty and desperate living conditions. Despite being held together by leaky pipes and crumbling walls, it was home to some 35,000 people; all tightly squeezed into paltry-sized rooms arranged on top of one another.

“I realised that in spite of its reputation as a dangerous slum it was, in reality, a working-class vertical village with people trying to get by like anywhere,” the photographer says of his first visit to the Walled City. “In a sense, its ordinariness was what was surprising, and what became the main point of the project: to show how people lived and worked in these extraordinary conditions.”

Despite the grating poverty and inequality it represented, Kowloon has gone on to inspire countless pop culture moments, from films like Bloodsport (1988) to Batman Begins (2005) and feature in video games like 2010’s Call of Duty: Black Ops. Girard puts the cultural fascination down to the fact that it also “represented freedom; a place where anything could happen and everything was tolerated.”

While demolition plans were put in place in 1987, the City was finally destroyed in 1994, spearheaded by the British and Chinese government’s intolerability for its health standards and poor quality of life. In response to the thousands of potentially homeless residents, the Hong Kong government issued out roughly $350 (£270) million in compensation to both residents and businesses of the City.

A year after its demolition, the City became a public green space, Kowloon Walled City Park, in the 330,000 sq ft area once home to the most densely populated spot in the world.

Girard’s project, aptly titled City of Darkness, saw him and fellow photographer Ian Lambot capture the spirit of the City. Currently exhibiting in Hong Kong’s Blue Lotus Gallery, City of Darkness sets out to illustrate not only the conditions, but the spirit of the community going about their normal lives within an abnormal environment entirely self-governed and neglected by the British, Chinese and Hong Kong governments.

Below, Girard tells of his experience documenting the Kowloon Walled City.

Kowloon walled city night view from SW Corner Hong Kong 1987, courtesy of Blue Lotus Gallery

Was it difficult to gain access to a (literally) closed-off community?

It might sound disappointingly straightforward but I simply walked in and began asking people. In the early days, there was some initial suspicion and hostility but after January 1987, when the HK government announced that the place would be cleared and its residents resettled, things got easier. There was an implicit understanding that the Walled City’s days were numbered and you were there to make a record.

Could you see a beauty in the space which you perhaps didn’t initially think you would?

There was definitely fascination from the beginning, and a sense of exploring an urban hybrid, a monstrosity even, which clearly had its own strange beauty, and was almost like a living thing. Seeing it for the first time at night, glowing at the end of the block, it was beautiful and intimidating. This building-thing that shouldn’t be there, but was.

What were some of the sounds and smells you remember experiencing?

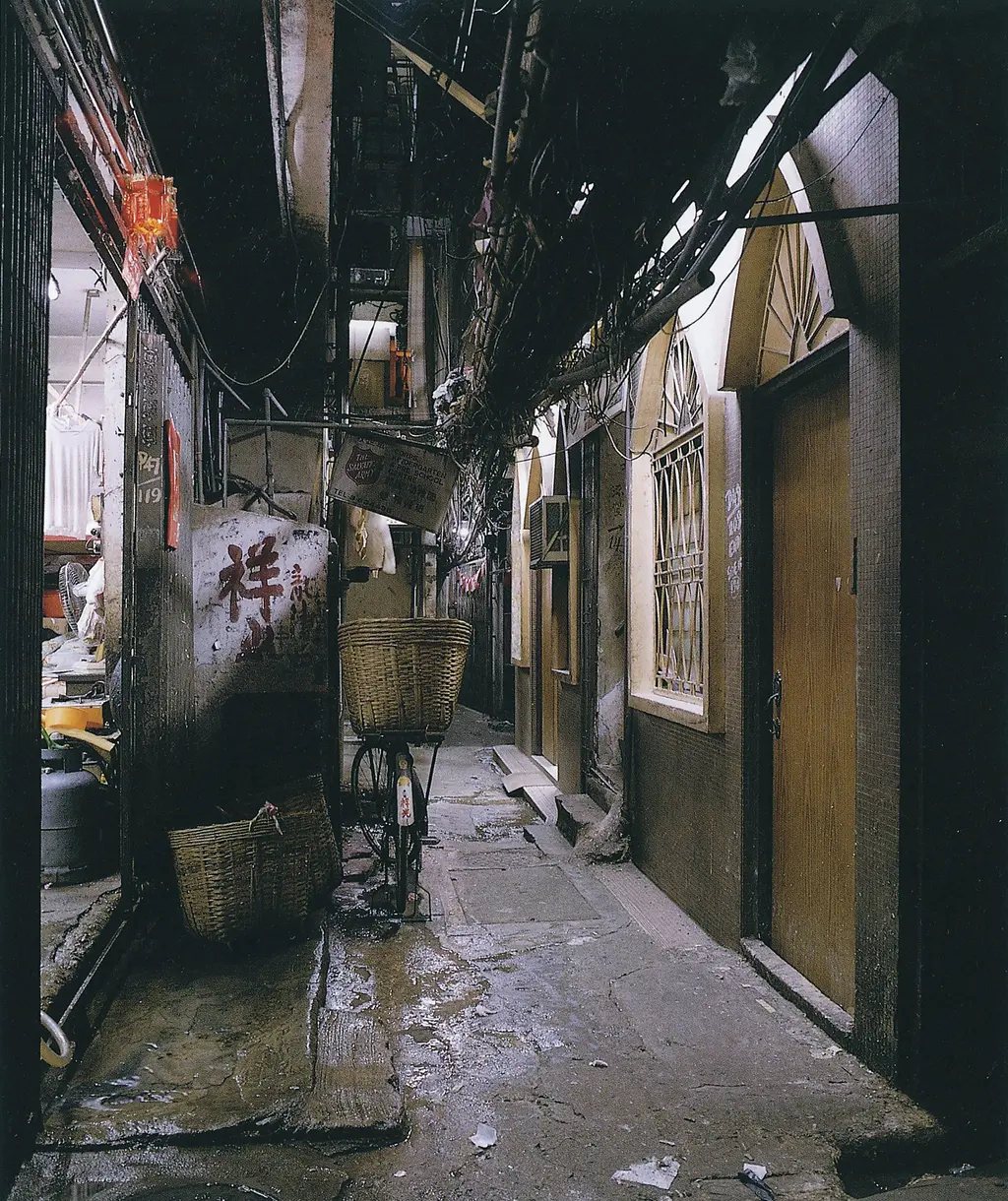

Summers in Hong Kong are notoriously hot and humid, and so the smells from the food production factories were pretty rank. At a barbecue meat workshop, men stripped to the waist would use blow torches to burn the hair off freshly-slaughtered pigs. Animal carcasses lay splayed on floors wet with water and blood. It could be pretty nasty. All the run-off from the shops flowed into open gutters that ran alongside the alleys.

As you walked through the Walled City’s alleys, the sounds would combine and separate as you passed various workshops: metal being pounded into shape, cotton-weaving machinery, music from radios and cassette players, mahjong tiles clattering, televisions blaring, air conditioning units humming, water dripping everywhere after it rained. It always seemed to feel damp in there even long after the rain stopped.

Walled city Tung Tau Tsuen Rd Hong Kong 1987, courtesy of Blue Lotus Gallery

Ian Lambot Lung Chun Back St, Hong Kong

Ian Lambot Dentists Chair Hong Kong, 1989

How did the Walled City’s world of drugs, prostitution and gambling compare to the outside metropolis of Hong Kong during the ’80s?

By the time I started photographing there in the mid-1980s all those things [drugs, prostitution and gambling] had migrated into Hong Kong proper, and it was mostly just the anarchic physical space that remained. Having said that, because there was almost no enforcement of Hong Kong’s civic codes [in the Walled City], it meant that unlicensed doctors and dentists could operate, and food production factories needn’t worry about visits from the health and safety department.

What do you think the City can teach us about freedom and oppression in 2019?

The Walled City suggests that people can get along just fine without regulation guiding every facet of life, especially in urban life. There was a measure of tolerance at the heart of what allowed the Walled City to function. How did 35,000 people manage to live in a single Hong Kong City block, in 300 interconnected high-rise buildings, none of them built with input from architects or engineers? Those were the questions we tried to answer in our books, City of Darkness and City of Darkness Revisited. But whether that is replicable or transferable to elsewhere I’m not sure. I’ll leave that for others to explore.

What do you think the photographs represent?

I hope they present a fair and sympathetic portrait of a place and its residents who made up one of the world’s most extraordinary urban communities, and who were slighted and judged to the end.

Which photographs from the project best illustrate the realities of living in the City?

I’d probably have to choose two photographs, one from a factory or workshop down in the bowels of the place, and one from the rooftop of kids playing in the late afternoon or people relaxing in the early evening with sprawling views of Hong Kong. Those two slightly contradictory views define the Walled City for me: the extreme physical compromises of the living and working spaces below against the slightly whimsical nature of the interconnected rooftops and the relaxed atmosphere up there in the evenings.