The exhibition showcasing prisoner-made art

Jeremy Deller (left) and John Costi (right), co-curators of the 2024 Koestler exhibition

From matchstick models of pool tables and papier mâché cartoon characters to portraits of the Queen, 200 works of art made by prisoners are about to be shown at London’s Southbank Centre, thanks to prison arts therapy charity Koestler Arts.

Culture

Words: Tiffany Lai

Photography: Alessandro Furchino Capria

Taken from the autumn 24 print issue of THE FACE. Get your copy here.

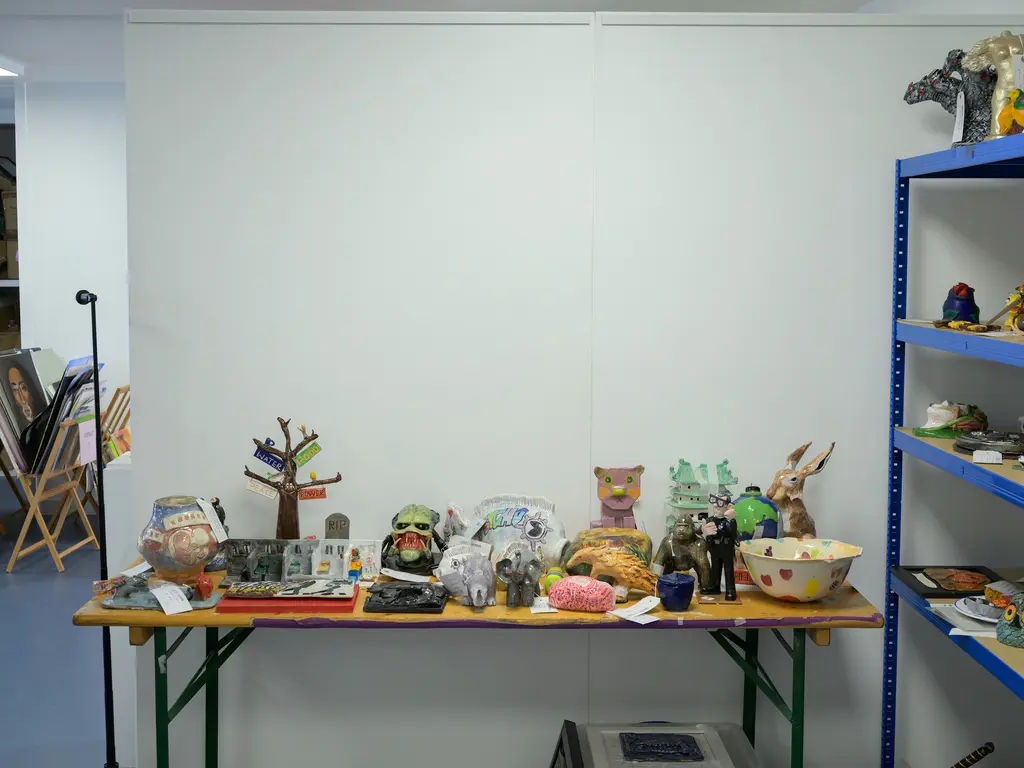

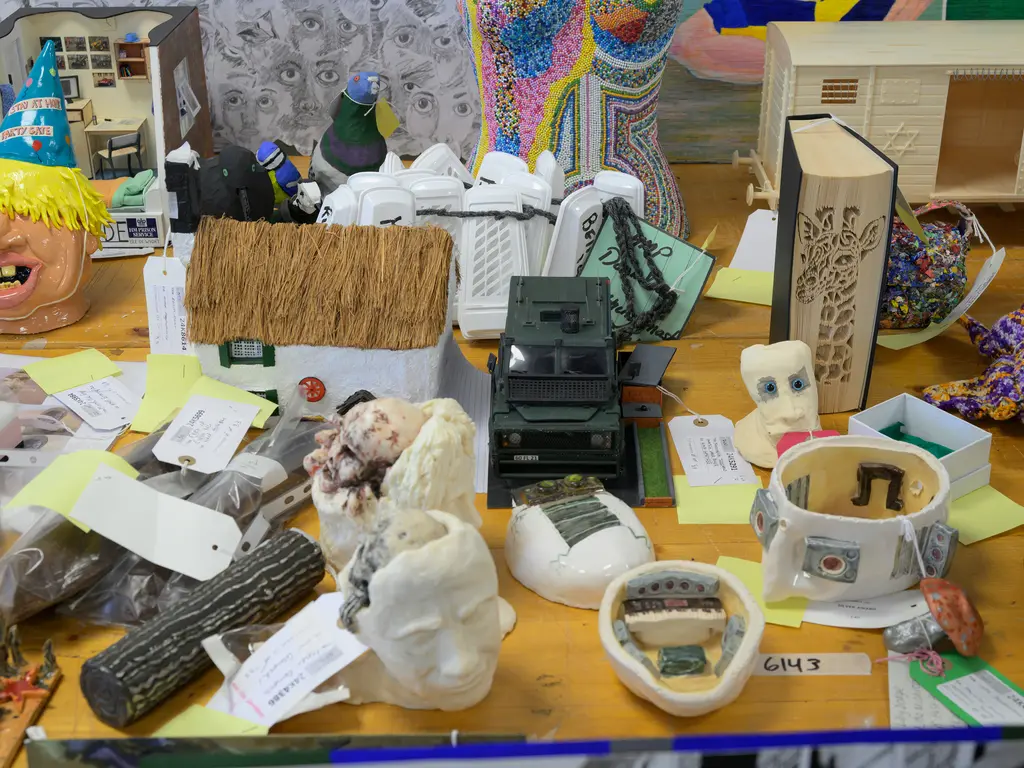

More than 7,000 pieces of art are stacked in the West London offices of Koestler Arts. The walls of the main space are lined with drawings and canvases of well-known faces such as Kim Kardashian, country landscapes and home comforts, such as a full English breakfast on a red-and-white tablecloth. Every surface is carpeted with intricate matchstick models of buildings, boats and even a functioning pool table. On the shelves in neighbouring rooms papier mâché Ricks (of Morty fame), ceramic heads and a pair of trainers fashioned out of loose-leaf tea jostle for space.

Unfortunately for the artists exhibited by Koestler Arts, they can’t visit their works in situ – even if many of them reside just a few hundred metres away. That’s because the collection of art, poetry and music that currently sits in their office was made by prisoners, many of whom are incarcerated behind the gates of the adjacent HMP Wormwood Scrubs.

The art that passes through Koestler isn’t usually shown to the public. But each year, the prison arts therapy charity hosts an annual scheme to award work by those who have been physically confined, and those that are shortlisted are available for anyone to see.

Thousands of entries pour in from penal institutions across the UK in the hope that they’ll be selected for an exhibition at London’s Southbank Centre. Competition is tough, with only around 200 slots available. But even if their work isn’t chosen, every inmate entrant gets something out of the experience – namely, feedback from a team of more than 80 judges, whose ranks this year include synthpop band Hot Chip, playwright Inua Ellams, ceramicist Rich Miller and comedian Jenny Eclair.

The artists can also sign up for Koestler’s mentorship scheme, which pairs prisoners with trained arts figures to support them after their release from prison. “A lot of what Koestler does is change perceptions of the kinds of people that are in prison,” says artist John Costi, as he intently studies a Kandinsky-esque abstract painting. “These people can do great things. They’re not written off, and that’s really important.”

John, 37, knows first-hand the impact the charity can have on prisoners. After being convicted of armed robbery at 18, he was sent to Feltham Young Offenders’ Institution for six years. Whilst incarcerated, he submitted a poem and an art piece to the Koestler programme and was accepted on a one-year HNC course in fine art at Kensington and Chelsea College after being moved to a prison for low-risk inmates. When John was released six months later, he joined the Koestler mentorship programme, enrolled at Central Saint Martins, graduated with a first-class degree in fine art and has gone on to exhibit work at Somerset House and South London Gallery.

Now, in a full-circle moment, John is co-curating the 2024 Koestler exhibition with Turner Prize-winning artist Jeremy Deller. This year’s title: No Comment, a purposefully straight-up re-use of the phrase commonly used by those being questioned in police custody. “We thought it was appropriate [because] we’re not trying to comment on it personally,” says Jeremy. “The work speaks for itself.

“We find out about ourselves when we make art – who you really are, who you want to be,” continues Jeremy. He’s worked closely with Koestler Arts for more than a decade and played a large role in connecting the charity with the Southbank Centre in 2008. “It’s a chance to find a different kind of person within yourself, not just the person who did something that means you’re in this place.”

Prisoners’ access to art supplies varies depending on the institution. Some only have found materials such as soap to make carvings from in their cell; others may have access to kilns or even recording studios. To accommodate this broad mix of mediums, the awards cover 52 categories, encompassing everything from fine art and poetry to music. There’s even a separate category for matchstick art (hence that miniature pool table), a skill that’s often passed from prisoner to prisoner.

“The most profound and impactful thing to me is just how hard these people are trying to be artists,” says John as he gives us a tour through the eclectic range of this year’s entries. “They are artists, but they’re trying to reinvent themselves in this image or 3D sculpture or whatever it is. When you see someone on that journey, the journey is the thing.”

Hi, Jeremy and John. When did the two of you first meet?

JOHN COSTI: At the [culture and education organisation] British Council. Jeremy was doing the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale [in 2013] and I joined him there. He had his show, English Magic, which was all Koestler entrants. Twelve of us went to Venice on a cultural scholarship and we did three or four days there. It was magical.

JEREMY DELLER: John was part of that, so we kept in touch. This year, Koestler wanted someone who had experienced the criminal justice system to be present and select [the art] with someone else. We were the obvious choice since we knew each other, which probably helps when you’re doing something like this.

JC: Being an ex-Koestler entrant, which is obviously why I’m here, I feel I’ve used Koestler to great advantage. I’ve got loads out of it. So hopefully other people who are entering can see what I got out of it, and learn that that’s available.

John, other than showing entrants what’s possible when they’re released from prison, how do you think your experiences help the curation of the exhibition?

JC: [I have] different perspectives. Like these works which have been drawn on to a prison bed sheet – I know that’s the colour of bedsheets in prisons. Lovely colour, but not for me. Not anymore.

JD: John picks up on the little things, even just initials in places and slang – most people won’t know what it means, but it’s actually of huge significance. For example, I didn’t realise that this picture is of a guy wearing a [yellow and blue] uniform because he’s a flight risk.

JC: It’s called an E‑man suit, which means you’re an escape risk or you’ve attacked an officer maybe. It means he doesn’t get to leave his cell or get a TV. He doesn’t get certain things and is lucky he’s got a phone in his cell.

What’s the colour of the standard uniform?

JC: It’s often just a grey or blue tracksuit. Sometimes you get what they call an Armani shirt, which is a blue-and-white pinstripe shirt with a little tag on it that says HM Prisons. It’s the same colour as an Armani tag, [and] they are really expensive to get outside because they’re smuggled from inside – these suits range from about £800 to £1,000 each on the black market or eBay.

I actually did a show recently where I had to make one myself, because it was so expensive. Whittling down the artworks from 7,000 to 200 for the exhibition is a big job. How are you making the selection?

JC: We’ve got some [guest] curators coming in tomorrow who will be helping us.

JD: They’re six mates of ours who we thought would be interested in doing it. I’ve chosen: Sports Banger, AKA John Banger, who runs a fashion label; writer and broadcaster Zakia Sewell, who is writing a book about Britain, so I thought it’d be quite good for her to see this hidden version of the country; Nicholas Cullinan, who is the director of the British Museum; and a curator called Aindrea Emelife, who curated the Nigerian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

JC: I’ve invited artists Larry Achiampong and Abbas Zahedi, who’ve both had some experience of the criminal justice system in terms of their friends going to prison. They avoided it by pursuing a career in art, so I’m interested to see their perspectives. I love the way they look at things and how they can pick out seemingly simple things and show they’re important.

Do you see any recurring themes in the work?

JC: We see a lot of portraits of Tupac. I mean, Tupac, for me, is probably one of the best poets I’ve ever heard and he was in prison. A lot of his songs are about a struggle that a lot of people in prison have been a part of, too.

JD: You see a lot of images of birds – they embody a spirit of freedom and they can fly away. There’s also a lot of the Royal Family and images of the Queen. I don’t know whether it’s because of HMP – like, Her Majesty’s Pleasure…

JC: When you go up in Crown Court as well, you’re [going up] against the Queen, so it’s almost versus her…

JD: So personal, isn’t it? But she still is depicted a lot. Charles is rising up a bit, but she’s still ahead.

Are those depictions positive or negative?

JD: It’s mostly positive, very patriotic work. There is less political work than you might think. You have a lot of work which is obviously about prison, but a lot of it is escapist – abstract or of animals or landscapes, ideal spaces. What kind of moods or energies are you drawn towards when looking at the pieces?

JD: Work that’s alive, that has an energy and stands out. All those things. You want to see things that you couldn’t imagine being made, where people have used their imaginations. It’s like any art, really: you’re looking to be surprised and have some sort of contact through the work. It’s not a normal group show in a way, as group shows often have a definite theme.

This is more like the Royal Academy summer show – the antidote to it, really. You spend a day here looking at stuff and you go home with it. It doesn’t leave you when you leave the building.

Are there any works that particularly resonate with your own prison experience, John?

JC: There’s this one [a portrait of a man in a cell with vibrating waves around him]. When you’re in prison, you feel like there’s almost a static, or there’s this fuzz. You’re not quite progressing, you’re just stuck in limbo. This is someone really trying to get out of that limbo, I think. You feel like: “Is this really my life?

How did I end up here?” There are also some pieces made from traditional prison materials, like pieces carved from soap. [John sniffs a carved cream skull.] That smell of buttermilk soap is so triggering for me. It literally transports you.

Do any pieces show how prison life has changed since you were incarcerated?

JC: There are a few pieces made from the inner cartridges of vapes. Ten years ago, you wouldn’t have that. They’ve banned cigarettes, so everyone vapes.

JD: It’s a new material. I suppose people find out they have skills they wouldn’t have found out [about] otherwise. But unfortunately, it takes going to prison to see: “Actually, I can draw and I can paint.”

John, were you aware of your skills as an artist before going to prison?

JC: I was into graffiti, but it took going into prison to believe that I could make art. I did have an idea that I was an artist, but I didn’t think it was possible. Then when it started changing my environment, or how I felt about myself and the beliefs I had, I was like: “I gotta do this.” I have to keep doing it, because it’s become my saving grace.

Is it easy to agree when it comes to curating the show?

JD: Yeah, it is actually, because we respect the other’s choices. We’ve been chosen for a reason – we’re not inexperienced at this. We know what we’re looking at and what to expect.

JC: I started off as an entrant for Koestler, then during my sentence I got day-release to have my interview for a fine arts programme [at Kensington and Chelsea College]. All of that wouldn’t have been possible without that first piece of praise or validation I received. It set me on this journey. It’s a really full-circle moment for me. Maybe I should think about doing some mentoring… That’s the only thing I haven’t done.

Because you had a mentor from Koestler, right?

JC: Yeah, Jo Davis Trench, who was a textiles tutor at Central Saint Martins in the ’80s. She helped me feel at ease in art spaces – [she helped me realise] that not everyone was suspicious of me all the time, because that’s how you feel when you come out of prison.

You’re told they are as well, that the local police are aware of your movements, and you have to have contact with probation. There are lots of different public agencies that monitor you. You lose your identity quite a lot and become disenfranchised with everything. It’s easy for that to feed into the idea that there’s “them and us”. So that mentorship made things easier for me, in terms of being comfortable going into spaces.

What sorts of things did you do together?

JC: She took me to the Southbank Centre and into cafés. I’d never really been into coffee shops. The places that were suited for me were bookmakers, pubs, caffs and dodgy kebab shops that had a bar in the back. That was where I was used to spending my time.

JD: Sounds great!

JC: It was, for about a week. When you do it for years, it takes its toll. The mentorship really helped with my identity and how I thought of myself. If you’d told me when I came out of prison that I’d be doing this – or even that I’d have a degree and a masters – I would have said: “Nah, that’s not on the cards for me.” But with the support of Koestler, I’ve managed to make it happen.

That’s really why I’m here, in more ways than one. I’m literally, physically here because I gave myself to making art, getting out of street life and all the stuff that goes with that. But also Koestler’s support has helped me get to grips with my mission as an artist and why I do what I do.

What was your submission for the programme when you were in prison, John?

JC: I submitted a poem called I Hate. I actually performed it last year at the Southbank Centre for an event with Koestler. It was about day-to-day life in prison, the things that I hated and how I’d become what I hated. [How I’d] become my own worst enemy. I was compelled to write poetry in that situation. I didn’t think I had any other choice, or maybe I just imploded.

At the time, I was waiting to be sentenced for over six months. That was tough, you just didn’t know what was waiting for you. And in that desperation, I engaged with anything, including religion. I’m not religious now, but there was definitely respite in it for me. I submitted that and an artwork, but I can’t remember what it looked like. It didn’t make its way back to me – maybe it was moved or Feltham just destroyed it. I used to imagine I’d find it in the old Koestler building. I never did, but I know it was probably one of the most important artworks I’ve ever made.

Are there any submissions in this year’s cohort that stand out as being particularly powerful?

JC: There are some artworks about IPP [Imprisonment for Public Protection], which is inhumane sentencing that was abolished in 2012. There are still 3,000 people in prison because of it. Even though it was abolished, they’re still stuck in the system.

IPP basically means you can only be released once you meet the criteria of the parole board. In order to do that, you have to pass all these courses, which aren’t available in most prisons, so you’re stuck in this cycle. There have been [more than] 80 suicides of IPP prisoners, [they are two-and-a-half] times more likely to self-harm, and they keep getting recalled to prison for minor things, such as staying at an unregistered address.

This piece [a red, collaged booklet on the injustice of IPP] is quite an important one for me. It says: “They have blood on their hands. There’s no hope, there’s no light at the end of the tunnel.” Every time they go in front of the parole board, the board says no, because they haven’t done these courses that are impossible for them to get onto. IPPs are so bad. I just don’t understand how we have that in this country. So I do have a bit of an agenda. I want that to be public knowledge. I want people to know that this is happening, because you wouldn’t believe it.

Have you seen any mentions of IPP reform in the Labour government’s agenda?

JD: It’s a bit early, I suppose. But what’s odd is that the first thing they started talking about was prisons, which I bet most people weren’t expecting. There’s obviously a huge crisis in the prison system. They’re moving very quickly because they know there could be a terrible riot. There’s overcrowding, people being killed, so they know that it’s critical. It’s become part of the national conversation. We’ve got to do something about it.

JC: I once heard that you can judge how successful a society is by their prison system, because how they treat their most unwanted is a reflection on them.

What do you hope the prisoners and the public will get out of the exhibition?

JC: [That] most people don’t end up in prison [by accident]. The problems start emerging in schools, where you probably get tarnished. You’ve gotten in with a bad crowd, or you might have ADHD, or you might not be that interested [in school]. You’ve already got this label, then you go to a referral unit.

When I went to a referral unit, I’m pretty sure that all they did was prepare me for prison. You’re put on a pathway: “I’m already being bad. I’ve already been put into this category of someone with no hope.” Then you go to prison and it’s confirmed. My mum said to me: “You’ll be dead or in jail by the time you’re 21.” Luckily, I went to prison at 19.

So it’s great to be able to give someone a new idea about themselves through feedback or selection, because I know how valuable that was to me. When I received feedback, it was the first time anybody who knew about art had looked at my work, and that felt incredible.

Visitors can give feedback in the show as well. There will be a form where you can write feedback directly to the artist.

JD: It means a lot [coming] from strangers, maybe more than anything else.

JC: When I got my feedback, I was like: “Mum, look at this, someone said that my artwork is good.”

No Comment will be showing at the Royal Festival Hall, Southbank Centre from 1st November to 15th December, with free admission