The French trio bringing queer club culture to ballet

They’ve thrown punches with Madonna, got down and dirty with Sam Smith and turned ballet dancers into ski-masked street fighters. Meet (LA)HORDE, the French trio who, as the directors of Ballet national de Marseille, have a vision of modern dance that might just be the future

Culture

Words: Olive Pometsey

Photography: Vitali Gelwich

Styling: Salomé Poloudenny

Taken from the summer 24 print issue of THE FACE. Get your copy here.

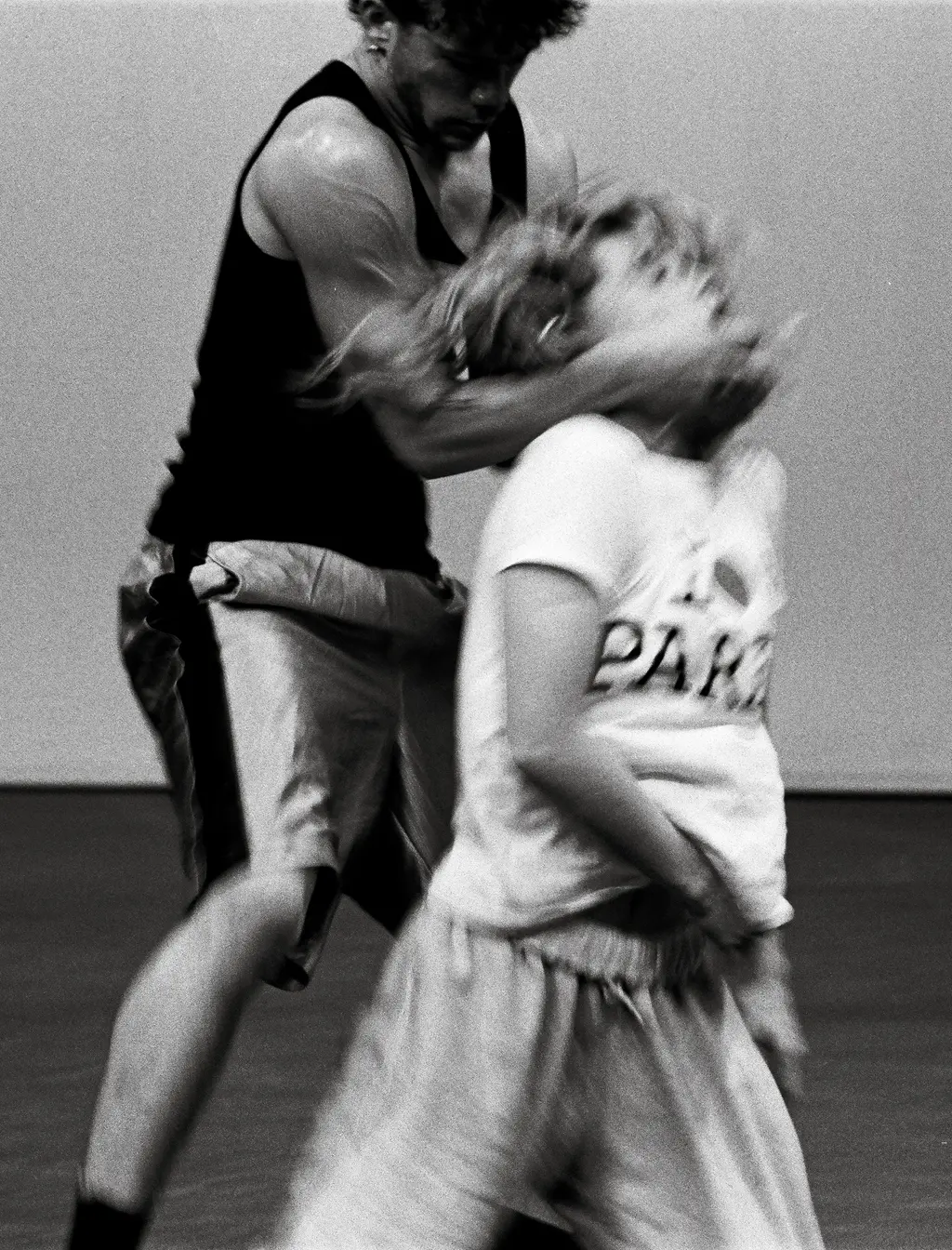

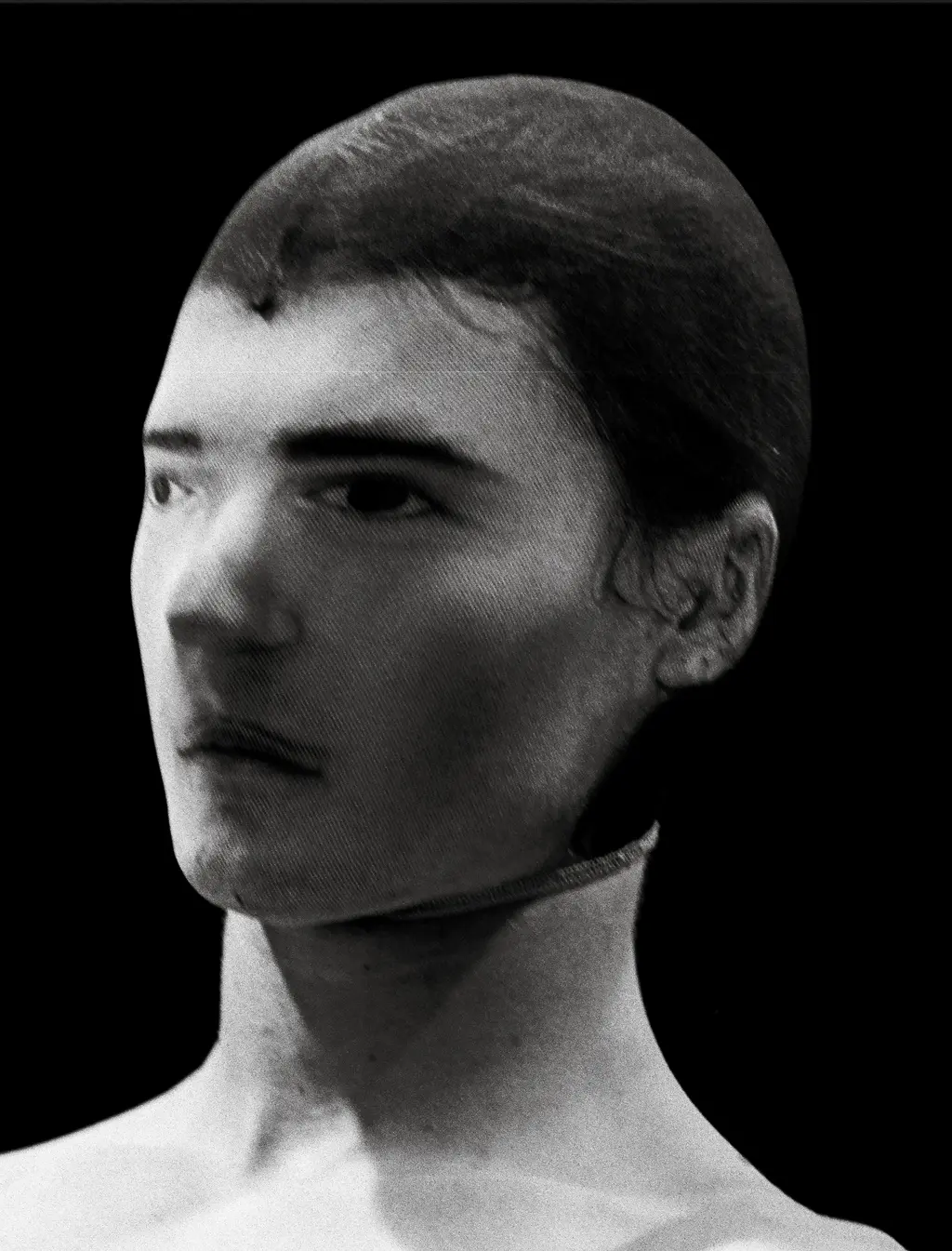

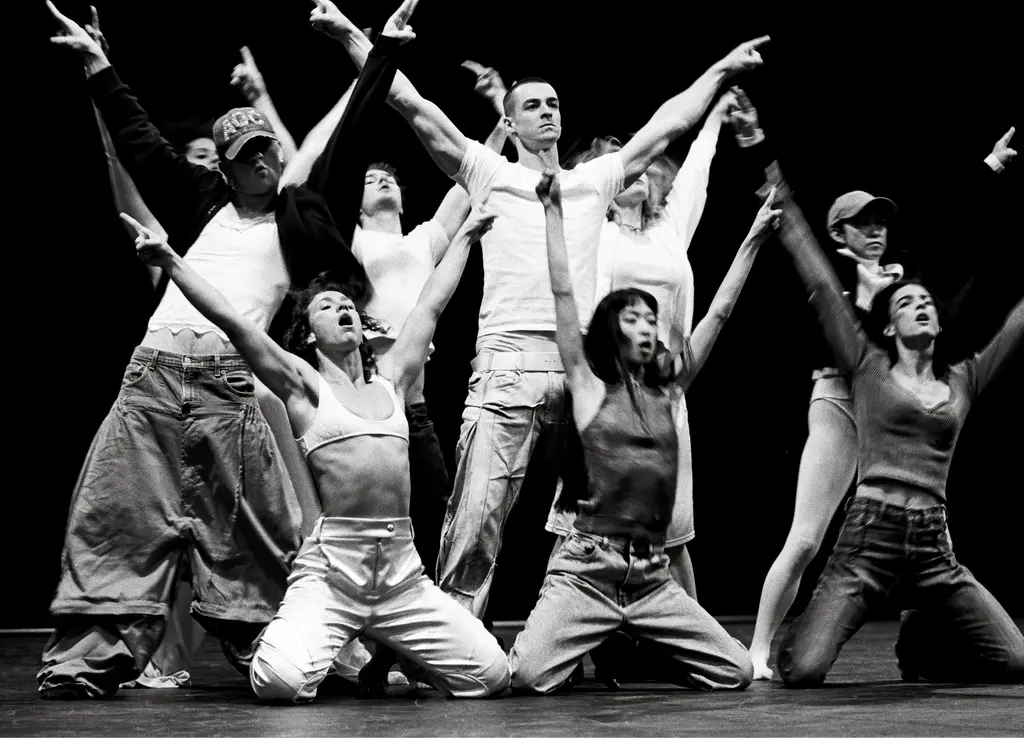

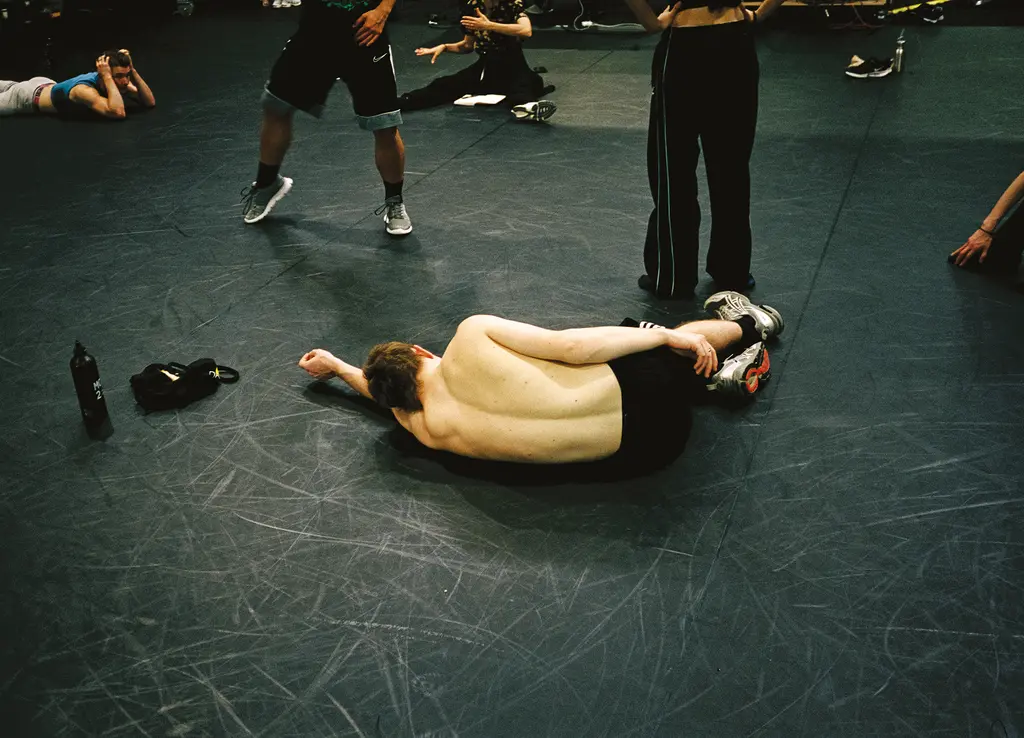

Things you might see at a (LA)HORDE show: dancers gyrating and sticking their fingers in each other’s mouths. Dancers going into battle wearing Juicy Couture tracksuits and uncanny valley face masks. Dancers in passionate embraces, fist-pumping the air, or wielding (fake) machine guns. Dancers sparring with Madonna in the middle of a laser-lined boxing ring to the beat of 1992 hit Erotica.

Fine. The latter wasn’t technically performed as part of a (LA)HORDE show. But Madonna’s recent Celebration Tour was choreographed by the strictly non-hierarchical French collective (la horde = the horde). Marine Brutti, 38, Jonathan Debrouwer, 38, and Arthur Harel, 33, are the hottest, buzziest and most sought-after names in dance right now, blurring the lines between pop music, ballet, contemporary art and creative direction.

They’re the kind of people that can pull off all of the above while holding down day jobs as the directors of one of France’s most esteemed dance companies, Ballet national de Marseille, and directing short films with Spike Jonze. Oh, and they also helped to bring Sam Smith’s kinky rebrand to life, choreographing the Unholy music video. Makes sense: the trio became friends 13 years ago on the dancefloors of Paris’s queer clubs. And it’s the values they learned in those sweaty spaces that underpin everything they do now.

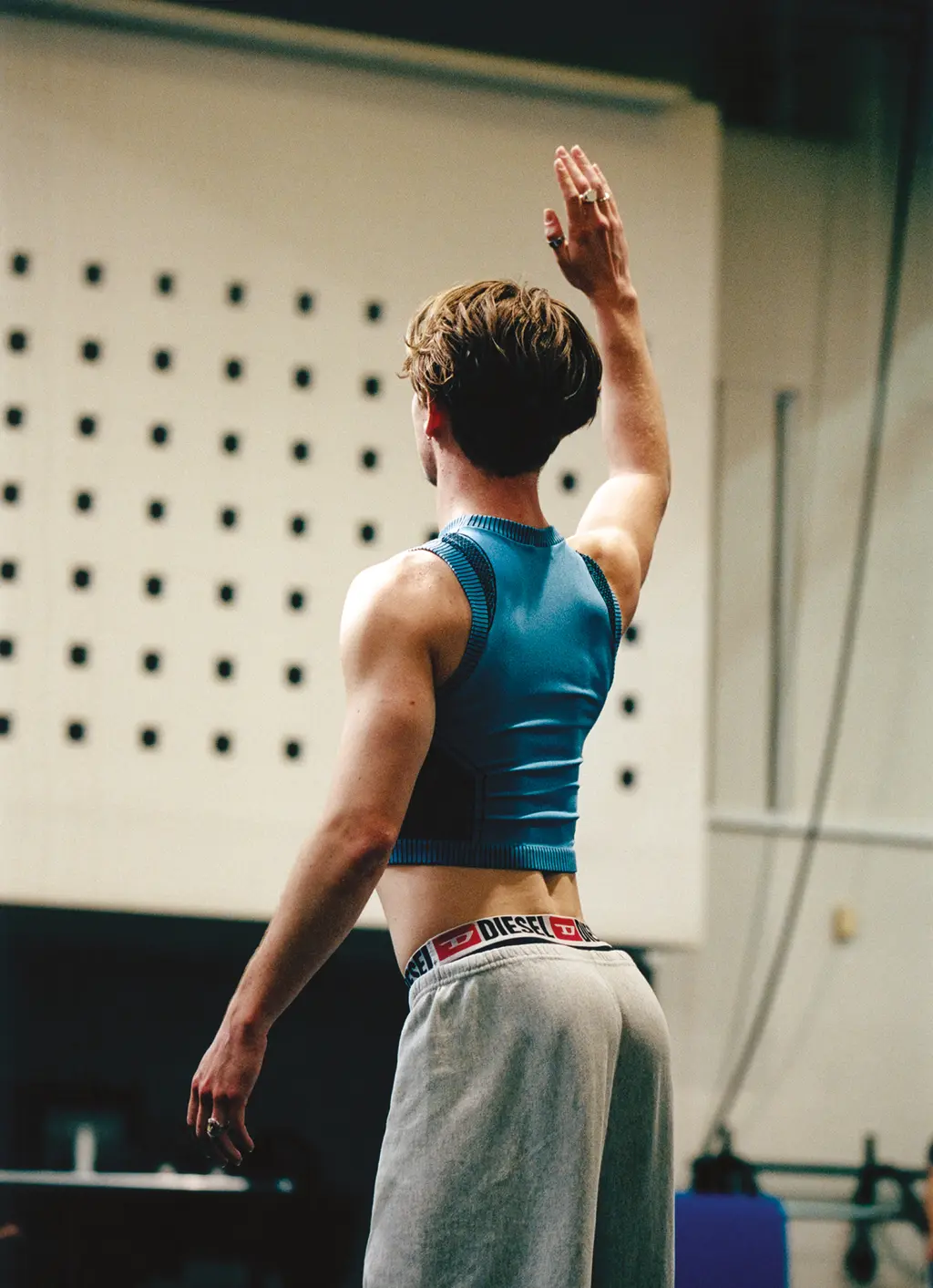

Their latest work (the one with the gyrating and the Juicy tracksuits) is Age of Content, a piece for Ballet national de Marseille that’s all about the TikTokification of contemporary culture. It toured across Europe this spring and made its final stop in Porto this month – to rapturous applause, no less. But (LA)HORDE don’t do it for the standing ovations. They’re here to reshape the dance world for the next generation – one body roll at a time.

What is (LA)HORDE?

MARINE: We are a collective of three. We are all from Paris and now we’re based between Paris and Marseille. When we are touring and working with international artists, we spend a lot of time away from home, so we’re a bit everywhere. But originally, we would say we are from Paris and are new lovers of Marseille.

ARTHUR: The collective is a person.

M: It’s an entity.

How did you become friends?

M: Jonathan and I met in art school in Strasbourg. We were, I think, 19 or 20 years old and studying performance for video and art. When we got back to Paris, we met Arthur, who was at the Conservatoire studying drama and dance.

JONATHAN: In the beginning, we were just going to the same places in Paris, living in this golden age of clubbing around 2010 that was really about creating community. [At the time] there was a new understanding of what queer culture was and how it was brewing in Paris. That was very important, I think, because this is where we were spending our free time but also where we were getting an elevated understanding of race, gender, the constitution of society and everything, through music and dance.

M: It has had a huge influence today on the work that we do because it gave us common ground on the values we not only wanted to share, but also defend on set and on stage.

When did you decide you wanted to work together?

M: It [came from] the struggle of [being] post-uni artists. When you don’t come from a family that is directly in the industry, it’s very hard to know where to start. We would have little jobs on the side and didn’t feel we could do it alone – and we were bored [of] doing it alone. So we were alway inviting each other [to collaborate on the jobs], whether it was directing a video for an artist – we get the camera, there’s no DoP [director of photography], so we do the lights on our own – or editing together.

There was also a workshop where we got to work with amateur dancers and ended up creating a one-hour show with them. [Through that we established] all these little protocols – sometimes we call it the “emotional capital”, an inner value that is based on emotion, where we can help one another to develop new ideas. At first, it was assisting, then it was working together as a group, and then came the moment when we had to put a copyright on it. We were like: it’s going to look silly if, at every different function, there is [all three of our] names on everything – people are going to think we’re not organised! So we decided to create an entity that is above us: (LA)HORDE.

How did you land on that name?

M: We decided to take a name that was polysemic [“capable of having several possible meanings” – Dictionary Ed] – it could mean a group of three or a group of thousands. There was this energy of movement because, when you think of a horde, you think of, like, a horde of horses. There is a conquest vibe.

A: There are also aspects of sci-fi. There’s a French author called Alain Damasio who wrote this amazing book La Horde du Contrevent, which is a philosophical, sci-fi journey of a group of people who are trying to find the origin of the wind. And “the Horde” is also a group that you can find on World of Warcraft!

J: We were playful and we were kids, trying to find a cool name that we can carry forever. It’s like looking for a rock band name or something.

Why do you think you work well together?

M: Maybe because we like to play. But I think we all have different reasons. I come from a very big household, I have a lot of siblings, so I’m used to these kinds of dynamics.

J: We also have common ambitions. We love to be able to play with big concepts.

M: Maybe it [feels] safe as well. We were at the start of the generation where everybody was telling us “everything’s going to shit”. When we were in art school, people were saying: “You’re never going to make it as an artist.” So we’re, like, pace yourself, brace yourself, help each other out. The sense of ego being set aside and serving a common base was more interesting to us. But it’s also because we were scared, to be completely honest.

How did you get involved with the Ballet national de Marseille?

M: When we saw the open call for [a new director for] national Ballet of Marseille, it was really oriented on youth. The company is a special choreographic national institution in France and there are many of them in different regions – it’s a project that was launched in the ’80s to explore culture across France and not concentrate everything in Paris. This was the utopia that people wanted to create for the future.

[Working in ballet] was never something that interested us career-wise – it never crossed our minds. But when the open call went out, it was oriented on youth, it was trying to see what the new modality [in dance is]. We came with a manifesto because we didn’t think that we would get it, to be honest. We were just like, “OK, it’s going to be a moment where what we have to say is going to be read by people who make dance influential today. It’s going to be read by the Ministry [of Culture], it’s going to be read by many different actors in this sector. Let’s engage [in] that conversation.”

Then we got nominated [and given the job], which was a huge surprise. But we’re very happy because we can develop things that we really believe in, but which also question our own vision. We have a company of 25 dancers and a production team of 25, so it makes things happen at a very different scale. We will forever be grateful for that.

A: We are very aware that this system is unique to France – the population decided to bet on what we call l’exception culturelle [a trade agreement where culture is treated differently to other products], which means [the arts are] publicly funded. It’s been created to let the younger generation take care of this concept. That culture is our society’s choice – it’s a political stance. Today, [this is] threatened, because in times when everyone is struggling, sometimes we forget that culture has its importance to society. As artists, it feels like we’re defending ourselves, when [in fact] we’re more trying to defend a broader vision of what society should be built on and [the idea of] culture as a necessity. As opposed to the [current] “culture snack” situation.

So it’s about the value culture brings to society as a whole rather than quick, digestible content where the sole purpose is to entertain?

A: And that idea between entertainment and content is what we’re questioning with our new show Age of Content, this new format [that shows] how we live together with culture and art. Entertainment, culture and art are not especially similar – one is more linked to the economic capitalist idea than others – but they’re also not against one another. But as artists, we still need to provide experimental spaces to be able to question the reality we are evolving in.

M: [With Age of Content] we wanted to display what we could say about dance today. We are exposed to these new formats and concepts [such as TikTok], but it’s funny because it’s very young and we all accepted it easily. We used to have movies, theatre, TV and advertising. Now we have this new creation that is “content”. We don’t really know whether it’s [simply] making videos, or if it’s advertising, entertainment, music, movement or dance. Or if it’s anything. As artists, we have to question the purpose of what we’re seeing. If I open my Instagram, as I’m scrolling I will see someone falling, then someone dancing, then someone talking about politics and then someone giving me free tarot card readings. It’s all on the same device, but we don’t have a clue what it means in terms of society and what dialogue it creates within ourselves. Why do we share this content so easily without questioning it?

How did you translate all those thoughts to the stage?

M: For the first tableau [in Age of Content], for example, there is a huge collective fight that happens, because there are a lot of fights online: in parking lots, girls pulling each other’s hair, stuff like that. But we also wanted to use this idea of

a globalised body. So we referenced Kim Kardashian in 2010, when she’s wearing this Juicy Couture set with hair extensions. [It was] the tipping point of when she really became the ambassador for this new era, whether you like it or not. There was a dreadful phrase when she was like, “your body is the accessory” – a new objectification of the body.

This was an ongoing process, where we were mixing layers of different realities. Then for the final tableau, we finish on what we call “TikTok jazz”. A lot of dancers feel like [TikTok dance creators are] the worst dancers on earth. It’s looked down on because it’s not coming from the top. For us, we’re like, “Do we question it because of where it’s displayed? Or is it problematic?” There’s also a lot of appropriation, a lot of wrong circulation. It brings a new discourse around dance: how it should circulate, where it comes from and how it evolves.

We added some jazz [dance], because it’s a style that’s looked down on today, but it emerged from Black culture in America before it became so commercial and was used in musicals. It’s still one of the dances that is the most studied in dance schools. So there’s this whole journey where we’re trying to decipher the new code that is in our bodies. Whether you can call it dance or just movement, we need to understand how these new images – and the new ways of receiving them – affect our bodies, our relationships, the way we move and how we experience our world.

You’ve also worked with incredible artists such as Sam Smith and Madonna. What were those experiences like?

A: When we were creating for Madonna, it was really like working on a pop ballet. There is an idea of “pop ballet” [as a theatrical concert] and Madonna was the innovator, with Prince and Michael Jackson, at the time. They were all born in 1958 and were the inventors of the visual show: theatre, ballet, video, sound, lights, performance, altogether, and that suddenly became the format for everyone else.The idea of pop ballet is about the concept of the show’s structure. Madonna comes from dance – she started [out] with [pioneering American dancer and choreographer] Martha Graham in New York when she was 19 or 20. She has this curatorial vision.

To produce the show, we had to work for four months, six days a week, eight to nine hours a day. It’s a real process of creating the show and not only finding movements to just entertain the crowd – even though what she does is very entertaining!

With Sam Smith, it was a very different journey. Because Sam is an institution, especially in England, and for them, it was kind of like, “I’m not 30 years old yet. There is something I want to explore as a pop artist and as a performer.” So it was about looking for meaning and a new layer of understanding in their work. It’s been a very sentimental and loving journey with them.

M: [With Sam] it felt almost like a 180. They had already come out as non-binary, but they wanted to explore more of that culture – and especially English culture as well, because you have great icons such as [performance artist] Leigh Bowery that are interesting to re-enact in today’s world.

What do you feel most proud of when you look back at 13 years of working together?

A: I’m super proud of the collective, the direction of the ballet and our work with different heroes: Sam Smith, Madonna, Spike Jonze [with whom they worked on a film for French electronic musician Rone]. We have a lot of important moments together.

M: For me, it’s that, now we have access, the ideas of empowerment that we talked so much about when we were younger, we’re able to put them in place. We’re all always afraid that, if we’re in a position of power, it could spoil us in the wrong way. When actually, if we understand that we can redistribute it and use it to empower more people, this is the thing we feel the most proud of: letting go and pushing forward.

There [are] many artists we helped here at the ballet who hadn’t found their place in the institution before. We’re very alert on this, to never lose touch with these realities. It’s the possibilities of bringing these queer values of tolerance and appreciation and non-exploitative interactions. The more we can speak about it, the more we can act on it and present a vision of what’s possible.

J: We’re very proud that the work we’re doing can make things evolve the same way elsewhere – even in the pop world. We are keen on making sure dancers are cared for and respected, because they give so much in their work. They’re not just disposable.

A: Yeah. Maybe it’s not super-visible, but our daily life is a lot of conversations, a lot of debates. That is life for us. It’s really a making process all the time. And we live for that.

CREDITS

TALENT Ballet national de Marseille – (LA)HORDE CREATIVE DIRECTION Marine Brutti, Jonathan Debrouwer and Arthur Harel ARTISTIC COLLABORATOR Valentina Pace DANCERS Jonatan Myhre Jorgensen, Eddie Hookham, Nina-Laura Auerbach, Yoshiko Kinoshita, Elena Valls Garcia, Alida Bergakker, Nathan Gombert, Amy Lim, Paula Tato Horcajo and Antoine Vander Linden PHOTOGRAPHER’S ASSISTANT Sebastian Back STYLIST’S ASSISTANT Maxime David MAKEUP Elisabeth Teycheney COMMUNICATION at BNM: Julia Beruea communication, PR: Laurence Alvart THANKS TO CCN Ballet national de Marseille for their availability and the use of their premises