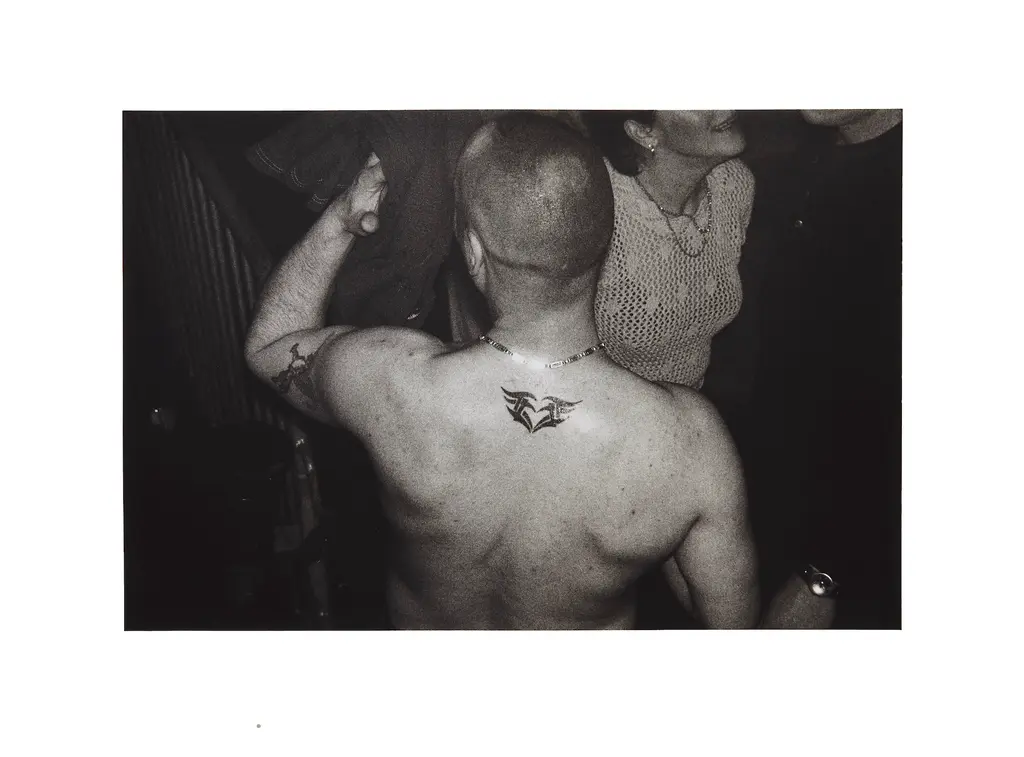

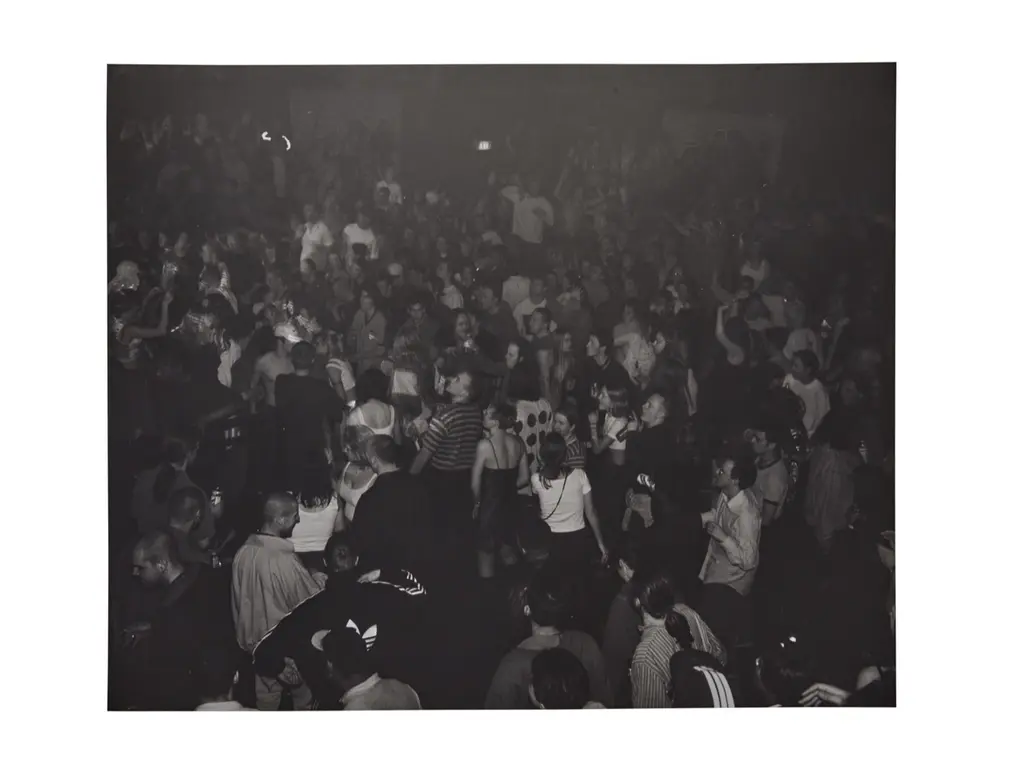

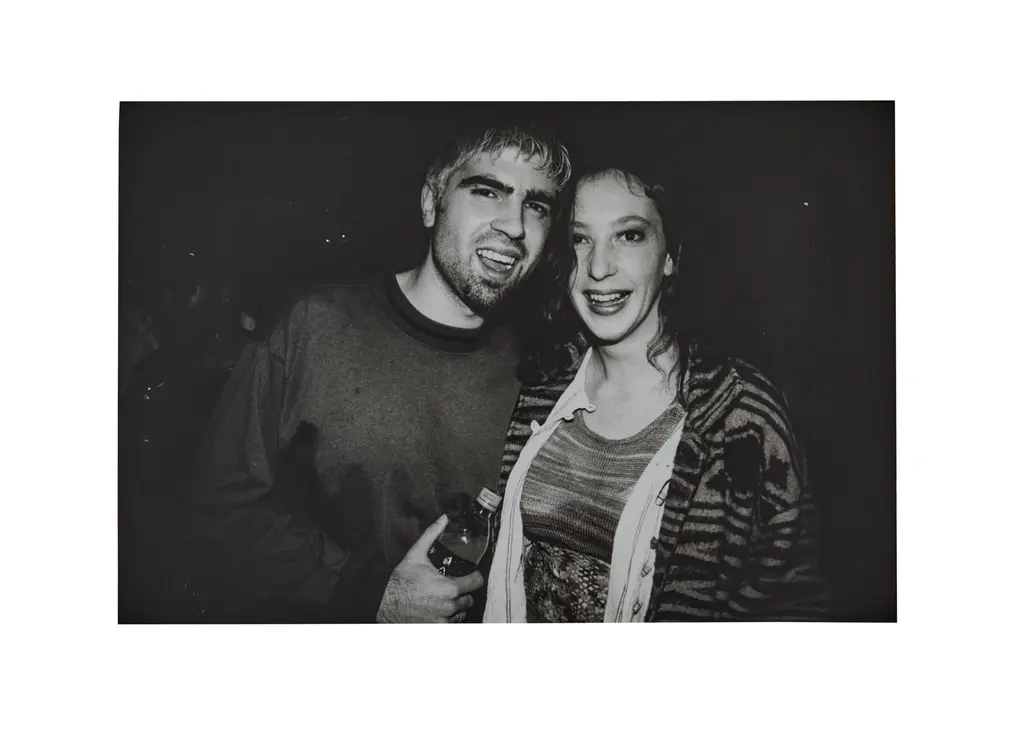

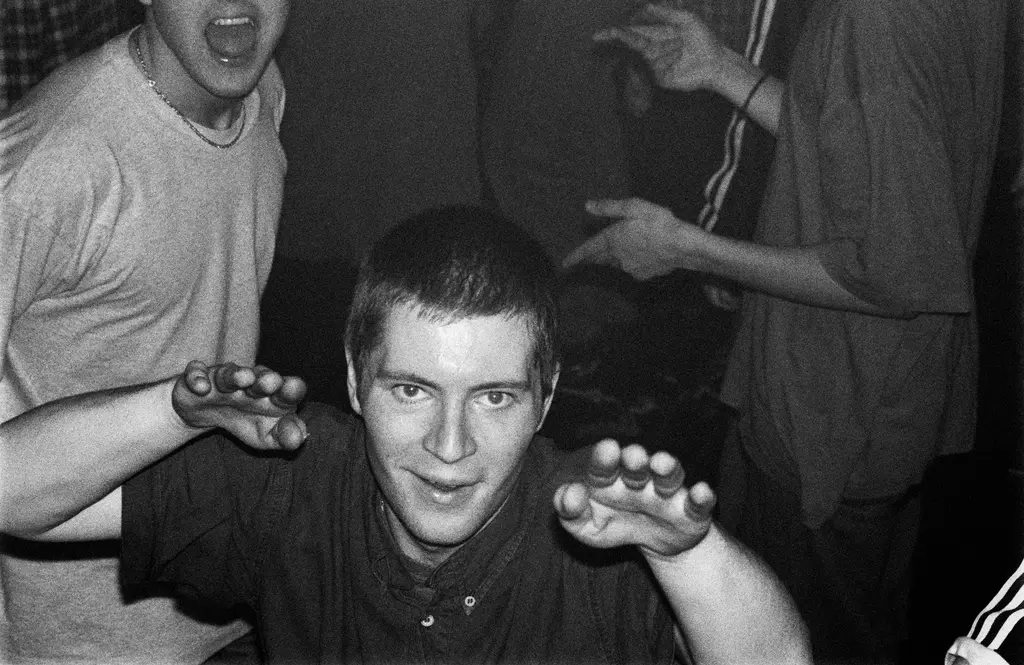

Terence Donovan captures the hedonism of Birmingham’s ’90s raves

Photographs Terence Donovan © Terence Donovan Archive

These images of the city’s cult club House of God were taken by the legendary fashion photographer. Then they were lost for 25 years – until now. His son explains their origins, and their journey to a new exhibition, In the Que.

Culture

Words: Craig McLean

Photography: Terence Donovan

In January 1996, Terry Donovan was, happily, in the rave and techno trenches.

DJing in his hometown of London, and back in Birmingham where he’d studied philosophy at university, the 25-year-old was spinning the likes of Vamp by Outlander, Energy Flash by Joey Beltram, Jeff Mills’ Mecca EP and LFO by LFO.

“It was a mix of historical rave culture – you could take anything from ’87, ’88 onwards – alongside some of the more metallic, fierce stuff that the actual DJs at the club were making,” he says of his sets, mentioning Surgeon (aka Tony Child), “the sound of UK techno at the time” and the genre’s local hero.

That location in England’s second city was The Que Club, housed in the historic, 1904-built Methodist Central Hall, with “35 to 40” rooms spread over three or four floors. Quite the venue, and it created legendary nights like House of God, where Donovan spun.

“I’d been a DJ for a long time by that point, and it was really hard to find that feral energy,” Donovan remembers, “where the crowd could overwhelm the sound system. And then you took that to the architectural scale of this venue, and the scale of 2000 or 3000, whatever the number of people in The Que Club was… I’d never done anything in my life where I wanted to say to my dad – who had a pretty special eye and had seen some pretty special things over the years – ‘Dad, could you come and look at this please?’ It was literally like a little kid saying: ‘Hey, I think this is cool.’”

Terry Donovan’s dad was Terence Donovan, the legendary fashion photographer. Alongside David Bailey, Donovan Sr. had pretty much captured the Swinging Sixties, shooting models and celebrities galore. He also directed sleek Eighties pop videos like Robert Palmer’s Addicted to Love, lensed myriad television commercials and snapped assorted royals, including Diana, Princess of Wales in 1987 and the Duchess of York’s engagement photographs.

And now here he was, at his son’s urging, aged 59, patrolling a heaving, throbbing late-Nineties rave in wee hours Birmingham.

“He was wearing a pair of black tracksuit bottoms and an old British army camo jacket, and he just wandered around and did his thing. You know, the nature of Birmingham and the nature of House of God, people were unimpressed by fame and celebrity,” says Terry, who went on to become co-founder of Rockstar Games and now lives in Colorado. “That’s one of the greatest gifts I ever got out of both dad and Birmingham – a constant reminder to treat everybody equally.”

Photographs Terence Donovan © Terence Donovan Archive

Photographs Terence Donovan © Terence Donovan Archive

Photographs Terence Donovan © Terence Donovan Archive

Photographs Terence Donovan © Terence Donovan Archive

Photographs Terence Donovan © Terence Donovan Archive

Over a quarter of a century on, those photographs are now being shown in real life – for the first time. These time-capsule black and white images – intimate, sweaty, euphoric, no little gurning – of a sweet spot in UK club culture by one of Britain’s greatest ever photographers? They were lost and forgotten, left curling and yellowing in a drawer in the Wolverhampton home of House of God co-founder Chris Wishart. Now, having been rediscovered in 2020 by Jez Collins, founder of Birmingham Music Archive, they’re finally going on public display.

In The Que, curated by Collins, opens this month at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. It’s an immersive recreation of a groundbreaking venue – alongside hosting club nights like Atomic Jam, Flashback and Spacehopper, artists including David Bowie, Run-DMC, Daft Punk and Primal Scream all played live – that closed in 2011. Donovan’s missing photographic record of a night at House of God forms part of an exhibition in which, says Collins, visitors can read about the history of the club and “get a sense of its importance to Birmingham – and its importance in terms of national musical culture”. True to that spirit, entry is free.

Alongside a specially made short film (which includes an interview with Wishart), there’s memorabilia such as contracts, flyers, posters, security jackets, T‑shirts and an overview courtesy of “a guy called Winston Smith who now lives in Canada. He just wrote this diatribe of what The Que Club meant to him, eight pages long, and posted it on Facebook – and that’s our introduction,” explains Collins.

As he puts it, paraphrasing somewhat, “you’ll walk into the gallery and it’ll be Winston saying: ‘We queued here, I put me drugs down me pants, go in, take me drugs, dance me face off, meet with people, the beats would come, the bouncer would do this, I’d go behind the stage and have a spliff with the DJ…’ Real verbal diarrhoea,” he says, approvingly. “And that for me is the essence of the exhibition. This is just someone who went to the club and it meant so much to him, that’s how he’s explained it. I think it’s beautiful.”

As for the contribution from Terence Donovan: I ask his son how much persuasion it took to get his esteemed dad – as in demand from Vogue as he was posh knobs’ jewellers Tiffany & Co. – to shoot a bunch of sweaty ravers in the middle of the night in an old church in Birmingham.

“There was nothing about the hedonism of it all that was shocking to him. He was incredibly comfortable in any environment”

TERRY DONOVAN

“Frankly, none,” answers Terry. “The invitation was there, he just booked a hotel and was game on. The only persuasion that was required was, at a certain point in the evening, I said: ‘I think it’s probably time for you to go home now, dad!’ This is four or five, six o’clock in the morning. And he’s like: ‘No, no, it’s OK!’

“But he had this existence in the Sixties and Seventies where there was no way to alarm him. There was nothing about the hedonism of it all that was shocking to him. He was incredibly comfortable in any environment. The moment he walked in and the place picked up pace, he just disappeared and started doing what he did.”

The photographs, previewed here for the first time, are incredible. They’re intimate, raw, unguarded. And they’re democratic, focusing on the kids on the floor, not whoever’s in the booth – and that includes his son Terry, who was DJing that night. Terence didn’t even shoot him.

“I might have been playing late, or I might have asked him to not,” thinks Terry. “But it was never about that. The crowd is what won at House of God. And Chris the promoter was really fierce about that. This was in the age of people doing Christ poses on the front of music magazines while they were DJing. If you got a little lairy, or a little high on your own supply, so to speak, you just would find yourself not on the bill the next week.”

His dad might have been there, done that, shot the Carnaby Street supermodel. But to Terry Donovan, these shots are of a piece with all his work.

“The images that he’s famous for are a distillation of what his eye would take in. My house in Colorado is covered with images from a trip we did to Morocco. We’d gone to visit a street market, and the road had collapsed on the way. The vehicle we were in couldn’t get through, and people were falling off the side of the road. The people we were with got the fear and said it was too intense. He was like: ‘Bollocks to that, we’re going, Tel.’

“And the images from within the street market have this parallel to me with what was going on at House of God – insofar as you needed a little bit of courage to wander through the door. And once you’re in, you get to see this really special stuff. And his photography was never limited to just fashion. Obviously, that’s what he’s famous for. But his ability to walk into that room and see unbelievable people was incredible. I have such good memories of that time, captured in the youth of everybody in those images.”

Photographs Terence Donovan © Terence Donovan Archive

Photographs Terence Donovan © Terence Donovan Archive

Photographs Terence Donovan © Terence Donovan Archive

Photographs Terence Donovan © Terence Donovan Archive

Ten months later, Terence Donovan committed suicide in his studios in Ealing, West London. He’d been suffering from depression, a condition triggered, the coroner’s inquest found, by steroids he was taking for a skin condition. I ask Terry whether there might have been any correlation between his dad’s state of mind that year and wanting to be more adventurous with the photography he was taking. Trying out new assignments, experiencing a new generation’s culture. Or is that an overreach?

“That might be an overreach,” he replies, nodding carefully from the car seat from which he’s Zooming. “There was no point in his life where you could have asked him to take a creative risk with any [project]. It wasn’t like, dad does this Monday to Friday. There was no point where he was in any way limited.

“So going to The Que Club and seeing all this stuff was not a big reach for him. And I don’t think there was any level of hedonism there that would have tipped his radar versus what was going on in the Sixties in London. It was just a cool thing to do for him.”

Nonetheless, Terry Donovan allows that there is added poignancy from the closeness of this job to his death.

“Going back to House of God to play after he died was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. Just standing there DJing, with tears streaming down your face”

TERRY DONOVAN

“Obviously, emotionally, the fact that it happened in the last year of his life, adds way more gravitas to the images for me. They would have been important anyway, but going back to House of God to play after he died was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. Just standing there DJing, with tears streaming down your face… And the fact that you say ‘image ’96, and death ’96’, it focuses the heart, even though it doesn’t really need to be focused very much.”

For Jez Collins, In The Que is, overall, about making these images resonate as more than something offering “rose-tinted nostalgia”.

“It’s timely that we’re showing these photographs and the exhibition itself now because I do wonder if we will get back to a pre-Covid sense of clubbing that’s anything like this. You look at some of the photographs that Terence took, and you see the close-ups of people together who don’t know each other, the tops are off, they’re lost in the music, in a really sweaty place… You would be sharing drugs with people – and at that time, smoking.

“But I’m hoping that it’s an evocation. I do want to have that connection, for [younger visitors] to ask: what does all this mean? What do these photographs represent about contemporary club culture and music? So it’s a prompt to look at the nature of clubbing now, and for people to recognise people like themselves in those photographs – and their behaviour now.”

In The Que opens at Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery on 28th April and runs until 30th October. Say it again: entry is free. What you waiting for?