The pioneering legacy of Nam June Paik

Merce by Merce by Paik: Part Two Merce and Marcel, 1978

Robots, a bra made from two TVs and collaborations with the 20th century’s most avant-garde minds – Tate Modern’s new exhibition extensively explores the artist credited as the founding father of video art.

Culture

Words: Karen Orton

Nam June Paik is the daddy of digital art. The Korean-American artist is as renowned for his experimental, entertaining, and sometimes shocking (more on this later), performances as he is for his attention-grabbing installations and video works loaded with unexpected insights into his personal life.

His work is an attack on the senses, not just for his ability to weave together the mediums of video, film, photography and performance, but also thanks to his knack for incorporating familiar memories and ideas surrounding his ancestral origins into his work. Widely credited as the founder of video art, Paik pioneered the use of TV and moving image in his work, sensing the importance of technology and media and anticipating their influence on visual culture years before the rest. All of which led him to coin the term “electronic superhighway” – a phrase used to discuss and predict the future of communication in the age of the internet.

Paik died at the age of 73 in 2006 yet his ideas feel eerily prescient in 2019 – Tate Modern’s new retrospective explores exactly this via 200 works from throughout his five-decade career – from robots made from old TV screens, to his mesmerising video works and his gargantuan installations. Ahead of the exhibition, we dive into the pioneering legacy of Paik via the people he’s inspired the most.

Self-Portrait, 2005

“HE WAS SUBVERTING THE FUNCTION AND USUAL USES OF TECHNOLOGY”

“He is one of the undisputed godfathers of media art,” says Haroon Mirza, who along with Doug Aitken, Cécile B. Evans, Trevor Paglen and Pipilotti Rist has been directly or indirectly influenced by Paik. As a member of the Fluxus art movement – alongside his friend and longtime collaborator performance artist, painter, sculptor and theorist Joseph Beuys – Paik was at the centre of a social circle that defined 20th century art and culture. (Think: John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Yoko Ono, Laurie Anderson, Peter Gabriel, Allen Ginsberg and Philip Glass, among others.)

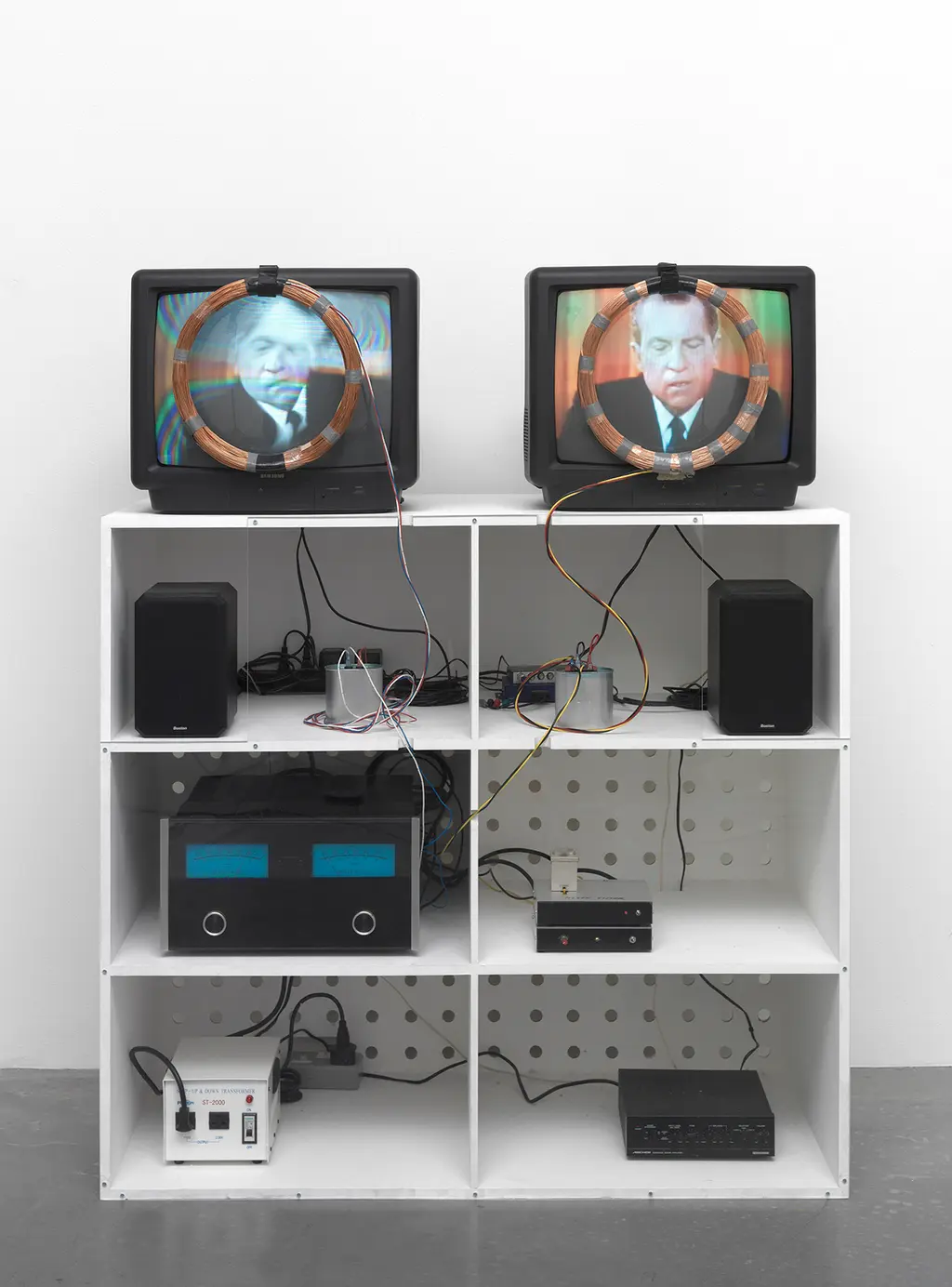

“He was always going against technology. A TV was always broken or manipulated in some way, rather than being used to show images, and video was heavily edited,” says Sook-Kyung Lee, senior curator at the Tate Modern. “He was subverting the function and usual uses of technology. Today we’re critical of the fundamental function of technology – so exposing its real nature is very interesting.”

“HE WAS OPTIMISTIC ABOUT THE POTENTIAL OF THE TECHNOLOGY”

Paik lived in Seoul, Tokyo, Düsseldorf and New York throughout his life. “From today’s perspective, it feels like another nomadic globetrotter, but actually historic conflicts and ideological tensions were always present in his lifetime,” says Lee, “He was trying to make sense of them, by looking at how the world has always been connected, rather than in conflict.”

He fled Seoul for Tokyo with his family because of the Korean War, and then went to study music in western Germany in the 1950s, where he collaborated with John Cage, and Karlheinz Stockhausen, and started creating experimental musical performance pieces with Fluxus.

Paik believed that technology and media would unite people while ensuring their lives were transnational and transcultural. “He thought technology wasn’t just for wars and conflict, but for resolution and bridging the world in a very idealistic way,” says Lee. “He was optimistic about the potential of the technology.”

A Tribute to John Cage, 1973-76

“I HAVE TO ENTERTAIN PEOPLE EVERY SECOND”

Paik’s initial taste of fame – and the start of his lifetime pursuit to humanise technology – came via his Robot K‑45 creation when he moved to New York in 1964. His first robot had breasts and a penis, it defecated white beans and it recited John F. Kennedy speeches, all while rolling around on wheels. Understandably, it was a hit. Years later, for his 1982 Whitney retrospective, Paik recorded a video of Robot K‑456 being hit by a car on the street that – somewhat surprisingly – elicited horror and empathy from onlookers. Later, in his Family of Robot series, he created sculptures of three generations of robot: parents and grandparents (constructed from older radios and TVs) and children and babies (using the latest technology).

In New York, Paik became part of a vibrant artist community. “He was good friends with other immigrant artists in Soho,” says Sook-Kyung Lee. “Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Jonas Mekas – people who fled their countries because of the second world war.” But in the ‘60s, it was tough going for Paik and many of his contemporaries, like Yayoi Kusama, who were not white and from the north American, western European art world axis. “He mentioned a lot in his writings and conversations, how difficult it is to make a wave as an artist,” says Lee. “He was an Asian man, and the art world was very white. There is no other excuse.”

At the time, the New York art world was about abstract expressionism and pop art. “Curators weren’t interested in these artists who were foreigners. At an early stage in his career, he joking declared that he was ‘yellow peril’. That was a problem he had to always overcome,” she adds. Paik himself stated: “I am a poor man from a poor country, so I have to entertain people every second.” Paik’s struggle to step beyond his outsider status in the art world was very real for the early part of his career.

“It must have been a solitary journey for him in the ’60s and early ’70s in Soho,” says Doug Aitken. “I can imagine it, the studio has all these cables wires and screens and you’re trying to make some kind of symphony out of debris – digital and electronic debris. That had very little precedence before him.”

Soon after arriving in New York, Paik met cellist Charlotte Moorman, a fellow Fluxus member who became his longtime muse and collaborator. They repeatedly made headlines together from their first work TV Cello that saw Moorman play a “cello” made from TVs on which other cellists were playing, to Paik’s Opera Sextronique (featuring a nude performance by Moorman in 1967).

Later in TV Bra for Living Sculpture (1969), Moorman wore two small TV screens that covered her breasts while playing the cello. And in 1976, for Project 05, she played a cello made from ice while naked, surrounded by radiators, until the instrument melted.

“To have someone who’s coming out of Korea, who’s working in New York in this Fluxus period, who was really mining an area that people view as almost being toxic – technology, moving image and appropriated imagery – that made Paik interesting,” says Aitken. Haroon Mirza agrees: “I think living in New York with people like Marshall McLuhan around him really paved the way for a new genre in art to emerge.”

Charlotte Moorman with TV Cello and TV Eyeglasses, 1971

TV Bra for Living Sculpture, 1969

“TELEVISION’S POSSIBILITIES AS A MEDIUM FOR PEACE”

Paik’s integration of Buddhism and technology was unprecedented and while he himself was a lifelong Buddhist, it was the tension within western interpretations of Buddhism that fascinated him. “When Paik met people like John Cage, he was surprised how Westerners were perceiving Zen Buddhism, as a Korean who grew up within it,” explains Lee. “This cyclical notion of the world and of time are part of Buddhism. His durational music and video works were culturally based on this.”

Two of his best known video installation pieces focussed on this: TV Buddha (1974/2002) and Zen for TV (1963/1990).

By 1974 Paik was Buddha. Almost. It was the year that his Living Buddha performance saw him meditate for hours next to a sculpture of a Buddha. Both figures were mirrored in a TV screen in front of them. “These loops, with no beginning or end in his video and musical works all seem very natural to me (as a Korean),” says Lee. “He was not trying to be innovative, it wasn’t something he invented – he adopted this narrative because it was culturally bound.”

Paik’s enthusiasm for conjuring up new uses for technology – and for captivating performance pieces – was a constant throughout his career.

In Good Morning Mr. Orwell (1984), Paik hosted a “global party” on New Year’s Day – it was his most ambitious work to date. He created a satellite installation between New York and Paris, with live reports from South Korea and Germany, featuring performances from Laurie Anderson, Peter Gabriel, Allen Ginsberg, Philip Glass, and his friends John Cage, Merce Cunningham, and Joseph Beuys. It was mischievous retort to Orwell’s pessimistic vision of 1984.

“I never read Orwell’s book – it’s boring,” Paik said at the time. He added: “I want to show (television’s) potential for interaction, its possibilities as a medium for peace and global understanding. It can spread out, cross international borders, provide liberating information, maybe eventually punch a hole in the Iron Curtain.”

In 1993 Paik won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennial for his dazzling room-sized installation Sistine Chapel. It was an impressive feat – 40 projectors were used to show a video succession of overlapping, blown-up images of David Bowie, Janis Joplin, Lou Reed, Cunningham, Moorman, Cage and Beuys. This chapel will be reconstructed at the Tate Modern for the first time since it was originally shown.

Several years later in 1986, he pulled off a second live satellite performance, Bye Bye Kipling, that spanned Japan, Korea and the US. Paik juxtaposed performances and interviews featuring Keith Haring, Philip Glass and Lou Reed with a group of Kabuki dancers performing to Western classical music that was played in Japan. It was signature Paik, referencing his artistic family, merging technology with eastern rituals – all delivered in the form of a huge spectacle.

Bye Bye Kipling, 1986

“A POST-INTERNET AESTHETIC THAT PREDATES THE INTERNET”

By creating a new language for digital art, Paik lay the groundwork for a new generation of digital artists, from Mirza and Pipilotti Rist to Cory Arcangel and Cécile B. Evans.

“In a strange way, I think his work went from extreme relevance in the ’70s and early ’80s, to an extreme irrelevance and then back again,” says Aitken. “Now we see much of his language is almost commonplace. The idea of split screen channels, of digital noise becoming rhythms and patterns, the idea of reaching out and appropriating these themes and turning them into a new narrative. I think in his way, he was just like a beautiful freak.”

Mirza’s work is similar to Paik’s in the way it subverts technology, albeit in new ways, via light and sound installations using electricity. He recalls first seeing Paik’s work at the Guggenheim while on a school trip, and getting hooked. “I was fascinated by a particular piece in that show,” he says. “It was a piece called Random Access Memory and consisted of seemingly randomly placed strips of magnetic tape adhered to the white gallery wall.”

These days, Mirza cites Paik’s work as more relevant than ever thanks to the way in which it merged various disciplines and technology. “It’s a post-internet aesthetic that predates the internet,” says Mirza. “[Marshall] McLuhan had also coined the term ‘global village’ by then so I guess people were already imagining technological connectivity. It also shows that what we call post-internet is merely a lens through which we contextualise a process – as opposed to what art making is.”

Both Mirza and Aitken have won the annual Nam June Paik Art Center Prize, alongside Trevor Paglen. The prize is given to artists and theorists who have “inherited the spirit of Nam June Paik”. “I was really surprised to get this award in Korea (in 2012),” says Aitken. “I thought ‘Why me? So strange.’ I found myself revisiting his work, thinking, ‘I need to give this a second look. Then I realised, he was foreshadowing much of how we see media now.”

TV Garden, 1974 – 1977 (2002)

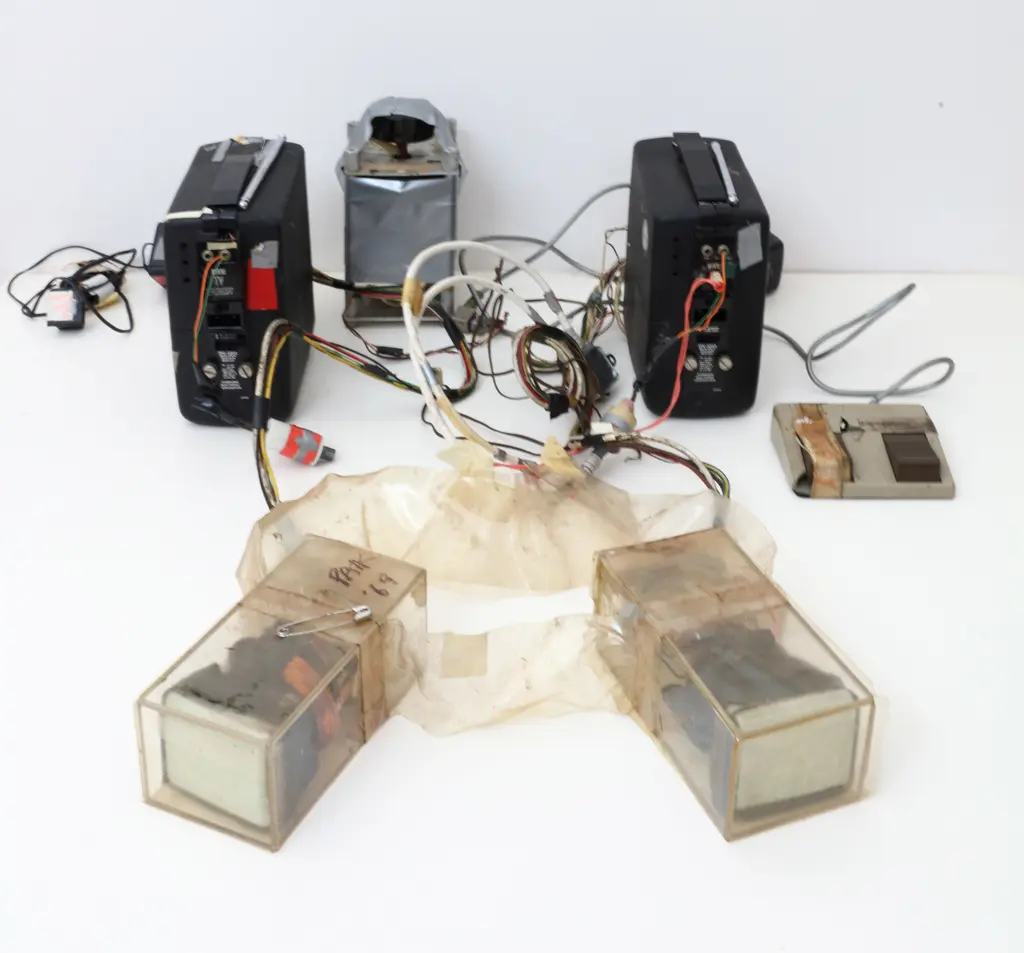

Nixon, 1965 – 2002

Surprisingly Aitken’s first encounter with Paik was a negative one. “I didn’t respond to his work, I saw it as something to push against. Being in New York in the early ’90s, the dialogue for myself and many of my peers was that we saw Paik’s work as opposition. His video art symbolised this hyperactivity of image, this chaotic noise-like approach. I was very interested in looking at the other direction. At the language of cinema.”

American conceptual artist Cory Arcangel paid homage to Paik’s Zen for Film via a pastiche titled Structural Film (created with an iMovie filter to mimic the dust and scratches of an old film). Meanwhile, Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto and artist Stephen Vitiello performed one of Paik’s compositions in 2013 as a public tribute to the artist. In an interview with Vitiello at the time, Sakamoto reminisced: “When I was a teen in the ’60s, I loved looking at the modern art magazines and I found a handsome Asian artist. That was Nam June Paik, who was one of the few Asian artists active in New York then. Naturally, he became one of my idols.” They met years later at Paik’s retrospective in Tokyo.

Together with Mirza and Cécile B. Evans, Vitiello will speak about Paik’s legacy at Tate Modern this October. “They are three different generations, all related to Paik,” says Lee, “we never really start from nothing as artists.”

Aitken agrees. “Paik’s work was able to look at the shallowness and shapeshifting qualities of images. It was able to understand the aesthetic surface value of media – almost like a never-ending wallpaper. A montage of information that’s continuously being replaced. In many ways, that’s the language that we live in now. The language of social media, the language of continuous acceleration. Now we’re living in a society of speed and surface. So in a strange way, we’re actually coming back to many of the concepts that he was mining at a very early stage.”

Despite Paik’s apparent optimism and belief in the potentially redeeming qualities of technology, it could also be said that he predicted the technological challenges we might face in the 21st century. “Is it possible for a star on the earth and a star in the heavens to meet?” wrote Paik. “That will be the ultimate challenge for the electronic superhighway… Needless to say, High Tech is not a panacea. It is just a local anaesthetic. There will be many unforeseen problems ahead.”

Paik might well have intuited the realities of technology in the 21st century and paved the way with his practice, but now it’s up to the next generation to continue this lineage of digital experimentation and to navigate exactly where the electronic superhighway will lead next.

Bag yourself two Nam June Paik tickets for the price of one using the code THEFACE241 until midnight 16th October.