Sheryl Garratt:“it’s time for a new generation to make something subversive of their own”

The former Face editor reminisces about the golden era of rave ahead of Sweet Harmony, an exhibition seeking to inspire countercultural activity.

Culture

Words: Sheryl Garratt

When Saatchi director Philly Adams came to see me with Kobe Prempeh, the curator of Sweet Harmony, the London gallery’s new exhibition about rave culture, I have to say I wasn’t that excited. People often want to talk to me about the acid house and rave boom. They’re making films and plays and documentaries (oh, so many documentaries, far more than ever make it to the screen). They’re writing books, or features, or studying it for their thesis.

And why not? Rave was the biggest, most inclusive new movement in popular culture for decades. And yes, I’m including punk – which, for sure, had a huge impact, but was actually quite tiny. Certainly in comparison to raves which attracted crowds of up to 25,000.

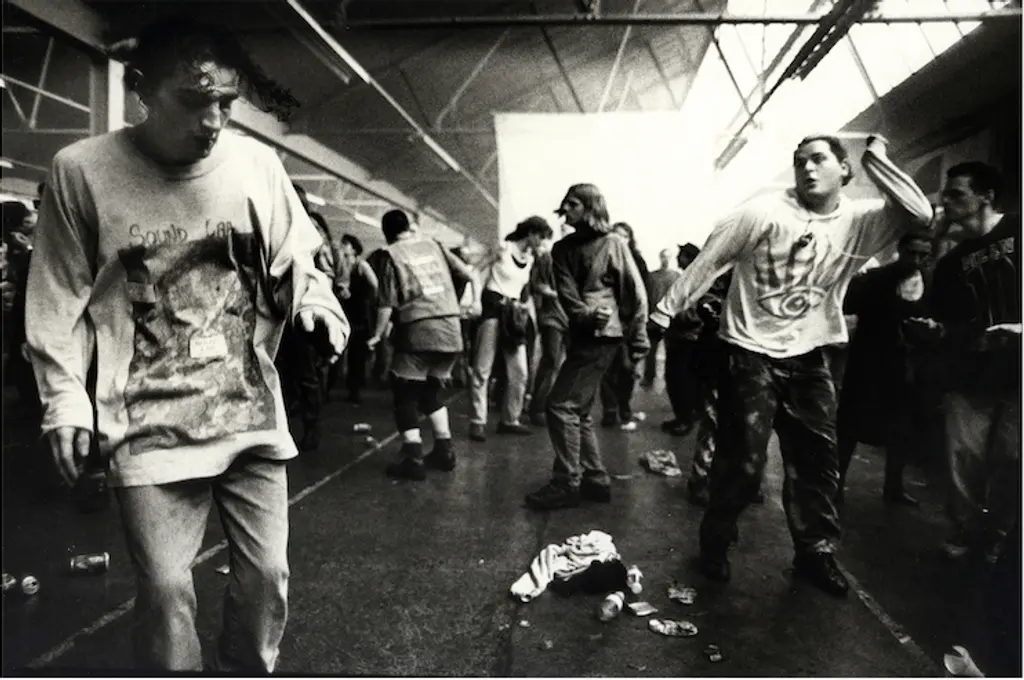

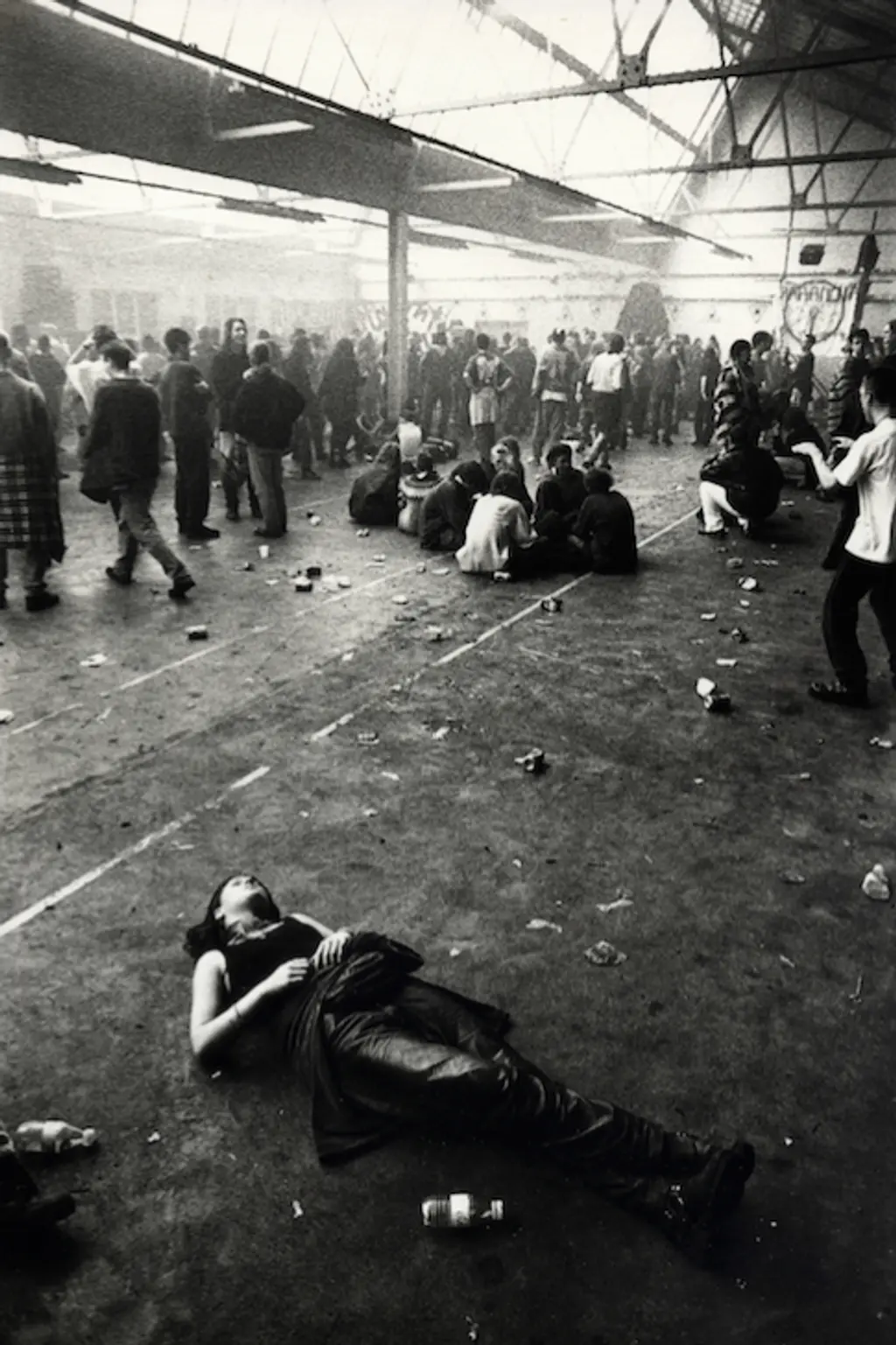

But after a while, no matter how great something was, you want to move on. It also seemed to me that most of these well-meaning researchers were missing the point. Club culture was never really about the DJs, or the venues, or the promoters, or even the music. Club culture was – still is, I hope – all about the people on the dancefloor. At their best, clubs are safe spaces where we can experiment, express ourselves, lose ourselves and merge with the music, the crowd, and become something bigger.

It’s not a time, or a place, or a sound. It’s a feeling.

Which, refreshingly, is exactly what the Saatchi team said when we met. Suddenly I was listening. Sweet Harmony wasn’t to be an exhibition that was strictly about rave culture, and certainly not one that was rooted solely in the past. It was about the adventure of getting to the rave, and about the energy and creativity it unleashed. About the ripples that are still reverberating through popular culture.

The artist Vinca Petersen calls this feeling “subversive joy”. Her room in the exhibition charts her journey from exuberant teen to committed clubber, then on to the free party/traveller scene, her journeys across Africa and Europe spreading joy with the help of a bouncy castle. But she doesn’t want it to be a history, capturing the past.

“I’m hoping it will inspire people,” she says, “to go find that feeling for themselves.”

So Sweet Harmony isn’t just a history. It’s more about trying to capture a feeling. The feeling we had in 1988 when almost overnight the London clubs turned from monotone to day-glo, enveloped by a tsunami of sweaty, hyper, hugging, smiley people. The feeling that all of the old divisions and barriers were coming down, that Mrs. Thatcher’s bleak declaration that “there is no such thing as society” was wrong. That we really were stronger together.

The feeling, too, in the long hot summer of 1989, of piling into cars and waiting at motorway service stations while clubbers crowded into the phone boxes, ringing the information lines again and again and waiting for directions for that night’s party to be announced. Then, as soon as it was, everyone scrambling to their cars, desperate to get there before the police catch up.

Because we all knew that once enough of us were in place and the music had started, there was very little the authorities could do to close it down. It was civil disobedience on a massive scale, an energy I saw echoed recently in Extinction Rebellion’s brilliantly joyful and defiant takeover of central London.

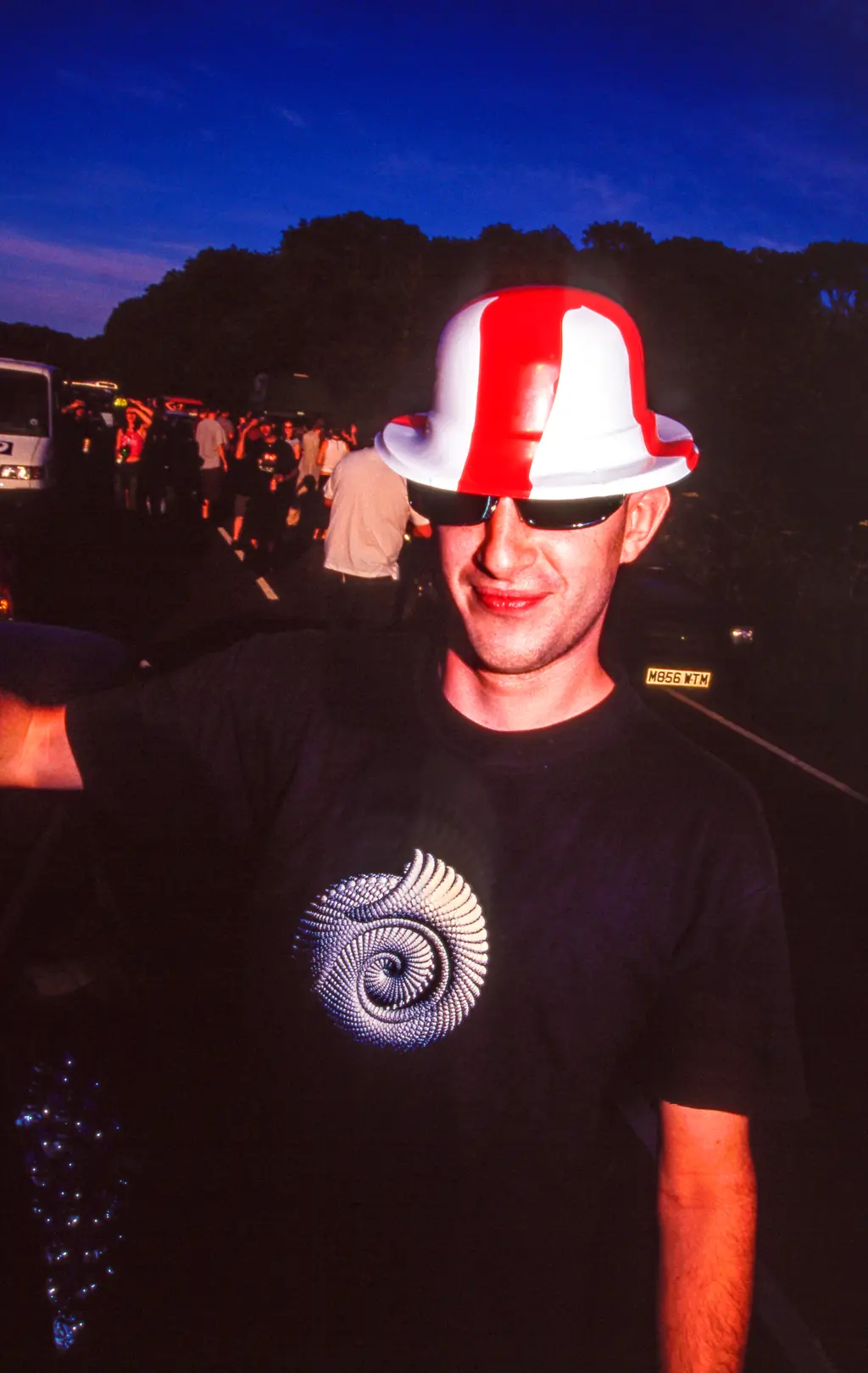

The feeling of finally arriving at the event, and finding a whole magical world had been built for our pleasure: funfair rides, lasers, huge sound systems, elaborate sets. And better still, the sun rising over it all in the morning, and being with thousands of other people from all over the country, all on the same buzz, the old divisions forgotten. One nation under a groove.

And the feeling of travelling across the country at the weekend, on our way first to the underground network of clubs that sprang up in the wake of acid house – then, later, to the superclubs that emerged after it became clear that the only way to contain the explosion of youthful joy in fields, aircraft hangars and abandoned industrial buildings was to grant all-night licenses to new city venues.

In the early ’90s, every weekend was an adventure, every town a destination: Blackburn, Nottingham, Manchester, Leeds, Liverpool, Birmingham, Sheffield, Mansfield. Even, on one memorable occasion, to a Paul Oakenfold gig in Shetland. But for me, the weekend nearly always ended on Sunday afternoon at Full Circle, a party in a pub just off the Colnbrook bypass near Slough, where clubbers from all over the country would gather to exchange stories about their exploits… and have just a few more hours on the dancefloor before the working week beckoned.

Lifetime friendships were forged in loo queues, on long car journeys, or back at someone’s house once the clubs had closed. Those years gave me a network of friends that extends around the globe.

We tried to capture this in the pages of The Face. In 1986 I was one of the first writers to cover the house scene emerging in Chicago, with DJ Frankie Knuckles taking me on a memorable tour of the city’s underground clubs. As the ’80s drew to a close I was editing the magazine, and that huge burst of energy in the UK gave us a new direction, a new audience, and endless inspiration – as well as a new generation of photographers, stylists and writers to collaborate with.

The shockwaves were felt not just in magazines, clubs, music and fashion, but also in art, literature, film. Pretty much everywhere.

What happened was a joyful collision of new music and new technology – and of course a newly rediscovered drug: MDMA. But it was also a reaction against the repression of the ’80s, of long grey years of austerity, division, exclusion and blaming. Which all seems eerily familiar right now.

Like Vinca Petersen, I hope the Sweet Harmony exhibition educates but also inspires. I have no idea if the next energy explosion will come from clubs, or even from music. And it’s right and proper that I don’t have a clue. It’s time for a new generation to make something subversive of their own. So, over to you.

Sweet Harmony runs from 12 July — 14 September at London’s Saatchi Gallery.