A Tár Is Born

Alongside Cate Blanchett, newcomer Sophie Kauer is the stand-out in Tár. As the brilliant psychological drama starts hoovering up awards-season love, we speak to the 21-year-old music student from Guildford – and tap her for an exclusive "Introduction to Classical Music" playlist.

Culture

Words: Craig McLean

It’s the afternoon after the awards season victory the night before.

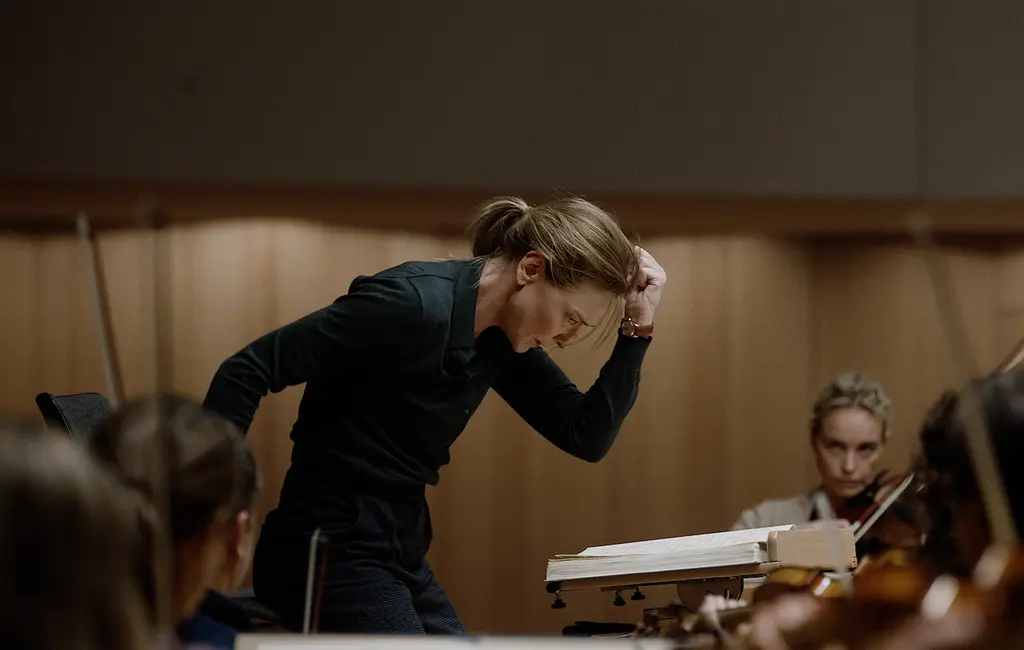

For her lead, title performance in Tár, Cate Blanchett triumphed as Best Actress in a Drama at this week’s 2023 Golden Globes. The win is the opening step of what feels certain to be a stellar run to the Oscars for this epic film about an imperious orchestra conductor accused of sexual misconduct.

As Lydia Tár in Todd Field’s near-three-hour epic, Blanchett has possibly never been better. Something to which the Australian’s newest – and possibly least experienced – co-star can humbly attest.

“I’m not surprised, frankly,” says 21-year-old Sophie Kauer, still reeling from making her acting debut alongside a double Oscar‑, triple BAFTA- and now quadruple-Globe winner who’s going to need a bigger awards cabinet. “She’s just a force of nature, that woman.”

Kauer, born in Guildford to English and German parents, plays Olga, a gifted Russian cellist who joins the Berlin Philharmonic, where Tár is chief conductor. The American maestro is at the top of her game: subject of reverent onstage Q+A’s with The New Yorker in front of a fannish audience (replicated in full at the top of the film), in total command of her craft and her orchestra, a take-no-prisoners tutor of young aspiring conductors, a rarefied talent in a rarefied world.

But as questions start being asked about her relationship with a troubled former student, the ambitious, driven Olga catches Tár’s eye. This doesn’t go unnoticed by the wife with whom she shares a coldly luxurious Berlin apartment, who also happens to be her concertmaster (principal first violinist). And, as Tár’s professional life (which is her personal life) teeters, Olga might be the rogue force that tips it over the edge.

Quite the role, then, for a cello student at the Norwegian Academy of Music, who was 19 when she was cast and had never acted before – a fact still not lost on her when we meet in a suite in a central London hotel on the day of the film’s UK premiere.

Congratulations on your acting debut, Sophie. What’s Olga’s game?

Thank you! The really interesting thing about Olga – Todd and I agreed this – is that we never fully make up our minds as to where she stands, as in whether she knows exactly what she’s doing in terms of the power dynamic aspect, or if she’s just totally oblivious.

Olga’s first performance is a lunch scene with Tár, where she just dives into her food. What were the instructions from Todd for playing that scene where she first sits down with maestro?

I remember Todd telling me that she’s staying with friends in Berlin, buying currywurst on the street, and this is probably the first proper meal she’s had. So you see me stuffing my face. Todd said: “Just eat as fast as you can, while you can still talk!” And it was a mix of things. The way Olga interrupts when the waiter clearly was talking to Lydia – she’s just not very self-aware. Not always appropriate in certain social situations.

But it’s part of her character, in that she’s just so self-assured. She just knows what she wants, and she doesn’t ever really try to appeal to anyone or suck up to them. She’s very caught up with her life and how she’s achieving her wildest dreams.

How daunting is it making your acting debut with Cate Blanchett?

She made it very, very easy, actually. I wouldn’t exactly say she’s a hard person to act with! She’s incredible. You just bounce right off her. She’s so kind, warm and always so encouraging.

The nice thing was that she was very open to giving me advice, but also to asking for advice from my perspective, as a musician. So that was quite amazing, to be able to pass on a tiny bit of knowledge to Cate.

How did you get the role?

I got it almost exactly two years ago now. I’d just gone back to Oslo [during lockdown]. Avy Kaufman, the casting director, told me that they’d sent out casting calls to all these conservatoires and music colleges everywhere. I actually know a lot of other girls who applied for it, which is quite funny. But I didn’t see the casting call, a friend of mine just forwarded it to me and said: “Oh my God, you’d be perfect for this.”

But I’d never done any acting before. So I was like: “Hmm, that’s not really for me, and why would I bother? It’s so much work to send in all these self-tapes when it wouldn’t get me anywhere.” But she really thought I should do it. My sister did drama A‑level, so she gave me some pointers. And then she was sitting on FaceTime reading the other side of the script while I was filming it.

I had no expectations whatsoever. Then the casting agent rang me out of the blue, right when I was in the middle of my end-of-first-year exams. “Can you send over a recording of the Elgar Concerto [that Olga performs in the film]?” I was like: “Sorry, I’ll send it to you in a fortnight, I’m really snowed under right now.” Again, completely oblivious as to how big the project was, because the casting call had been so vague. It was just: “Cellist between the ages of 18 to 25. Who could be Russian and feel comfortable in front of camera for a film shooting in Berlin in the autumn of 2021.”

Did you know Todd Field was the director?

Yes. Then he rang me after I kind of brushed off the casting agent. “Are you really serious about getting this part? We’re really, really happy with everything we’ve seen so far. So if your playing is at the level we hope it is, the part is yours.” I was like, “Christ!” So I got [the piece] under my fingers in a day.

Then suddenly, they were sending all these cryptic emails: “You’re at the top of a very short list… You’ve been approved by the studio…” But me not being familiar with any of this meant I had no idea what it meant. Then I was on another call with Todd and he started telling me all about Olga. I was like: “Have I actually got the part? No one’s actually told me outright!”

Your parents first got you cello lessons aged eight because they noticed you responding to classical music. How were you doing this as a child?

As a six-year-old, I was telling my parents that they had bad music taste and to stop listening to pop music! I was like: “What is this? No, we’re not listening to it!” Also, I used to want to be a figure skater. So they saw me really react to the music a lot there.

I was a child who had a lot of emotions, and [later] they could see that the cello was a very good outlet for me. It was a way I could say a lot of stuff that you can’t always articulate when you’re eight or nine.

So you were more a Ravel’s Boléro kid than a Little Mix little girl?

Maybe not Ravel’s Boléro, but other pieces! But I listen to all sorts of music now, I think it’s really unhealthy to only listen to one: jazz, indie, Beach Boys, everything.

What was on your Spotify Wrapped for 2022?

Ooh, it’s hard to say because obviously a lot of your gym playlists go to the top, and they’re not always the best stuff! But I listened to a lot of film soundtracks last year. A lot of Hans Zimmer, [Tár composer] Hildur Guðnadóttir is amazing. And Little Dragon, I love them. And don’t tell my cello teacher in Oslo, Torleif Thedeén, but I always listen to his CDs as well. So he’s always up there quite high!

So that’s not you sucking up to the distinguished Swedish instrumentalist, you genuinely like listening to him?

Yes! It was a really funny story because he is actually one of my absolutely favourite cellists. One day, I was just like: “He has a class, why am I not applying for it?” So then I was like: “Why don’t I? I’m going to do it.” Then I applied and did the crazy thing of learning Norwegian in 10 months.

“People always go: ‘So tell us which cellist inspired you to play?’ No, it’s because I got to sit down”

What was it about the cello, of all the instruments, that spoke to you most as a child?

It’s not a very romantic story! We had the choice to choose violin, cello or double-bass. But I didn’t wanna play violin because you had to stand up while playing. And I thought it was too squeaky, and double-bass was too growly and huge. So despite being very hyperactive, I chose the cello because you got to sit down while playing. People always go: “So tell us which cellist inspired you to play?” No, it’s because I got to sit down.

Obviously you had the musical skills. The acting was all new to you, so you took some online lessons from a proper screen legend. What did you learn from Sir Michael Caine’s acting tutorials?

A lot of really good technical stuff. Not blinking a lot. When we do over the shoulder shots, which eye to look into. Don’t look at the camera – except when they tell you to! How not to overdo it. How small things make a very big difference

[On set] it was interesting to watch the actors. It was very much a masterclass. I learned a lot from Cate, actually. I asked if I could watch other actors film their scenes, and I noticed that she’d ask how big the frame was. If it was much bigger, she’d maybe turn her whole head. If it was closer, all she’d do is blink and it would make a huge impact… Yeah, I was on set way longer than I should have been!

There’s a pivotal early scene in a classroom at the Juilliard music school in New York. Tár lectures the students on representation and dismisses their concerns about which 18th/19th century composers – to paraphrase her, all “white, church-going Austro-German men” – may or may not speak to younger students. How resonant – i.e. real – was that situation to you?

They do happen actually, especially now. Some people really do refuse to play music they don’t identify with, or by composers they don’t identify with. And I do sympathise with them. We need to be a lot better at including other genders and cultures and ethnicities in classical music, and we’ve been a bit slower to evolve than some other art forms.

But I don’t think we can just try to erase the majority of music history. It’s definitely good that this discussion is being had. But in my opinion, you can’t just throw it all out because we can’t change history.

How big a problem in the classical world are intolerance, abuse and sexual harassment?

The Independent Society of Musicians released a study right as the film was being released in the US [late last year]. And it said it’s actually the worst it’s been for a very long time. So it’s perfect timing that the film is coming out now, because it really brings all these issues to light.

That’s not to say that this doesn’t happen in other industries as well. But, yeah, it’s a big problem, especially after the pandemic. A lot of freelance musicians are struggling because of having missed work opportunities. So they’re worried that if they speak up that they won’t be re-booked, or face repercussions. And a lot of people are still very economically unstable.

There has been discussion of these toxic issues within other industries: film and television, and popular music to some extent. But classical music hasn’t had that light shone on it. I think that’s partly because it’s seen as a rarefied, separate world that a lot of people wouldn’t have much of awareness of. But Tár is helping bring the issues within that world into more mainstream conversation.

It’s interesting you say that, because I always felt that, in popular culture, classical music is regarded as irrelevant or stuffy or not taken seriously. That’s always really upset me. I know that a lot of people say that, if they don’t understand every single sharp, flat or chord, that they can’t enjoy it.

That’s just not true. The whole point of classical music, like cinema, is to move you or transport you to somewhere else. People often get blinded by their prejudices instead of actually just giving it a chance. It’s always been a big goal of mine to try and bring classical music to a wider audience and destigmatise it – or take away some of the fear.

I thought by doing this film that I could really help, so I’m really pleased to hear that you’re saying that it has brought it to the attention of a wider audience!

On that point: for any FACE reader your age who loves their music but is daunted by the classical world, many thanks for your introductory playlist (below). Could you also suggest an entry-point orchestral piece?

Absolutely. There are a lot of very, very creative artists reworking classical music. One of them is this amazing man called Víkingur Ólafsson. He’s signed to Deutsche Grammophon. What he does is so beautiful, but very accessible. He has loads of different albums to choose from, and everything he’s done is really good, but there’s a very lovely album called Reflections.

You have 18 months left studying. What’s happening after that? A combination of acting and music? One or the other?

I’m still seeing what happens, because my life is not going to plan at all! But cello has always been my absolute rock through everything, and I can’t ever imagine my life without playing. I have no plans to abandon that whatsoever.

I don’t like people shoeboxing you and telling you that playing the cello is all you can do, or you’re not serious enough about your career as a musician. Especially now, there are plenty of other musicians who also write poetry, or do podcasts, or they paint, or they’re political activists. So I don’t see why, if another amazing project were to come along, I couldn’t do more acting.

Would you take a non-musical acting role?

Oh, yeah, absolutely. Have I had any offers? Maybe! But Tár is quite a hard film to top, both because of the amazing actors and director, and then also the musical people. It was a dream come true.

Tár is in cinemas now

Listen to Sophie's playlist of classical music, exclusively curated for THE FACE