This is the gayest love story ever told

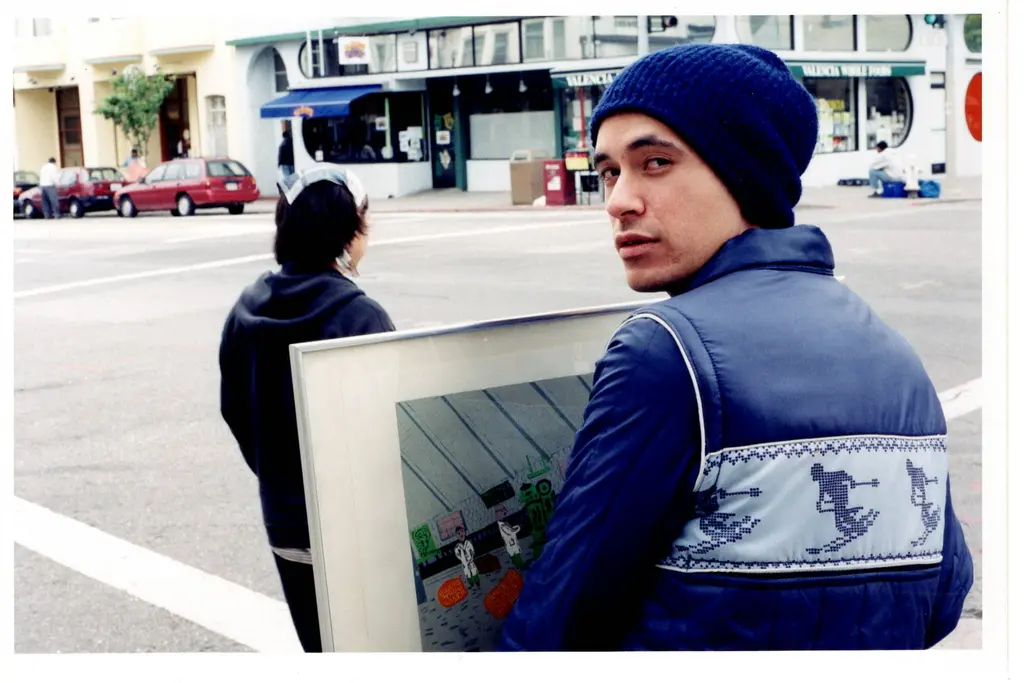

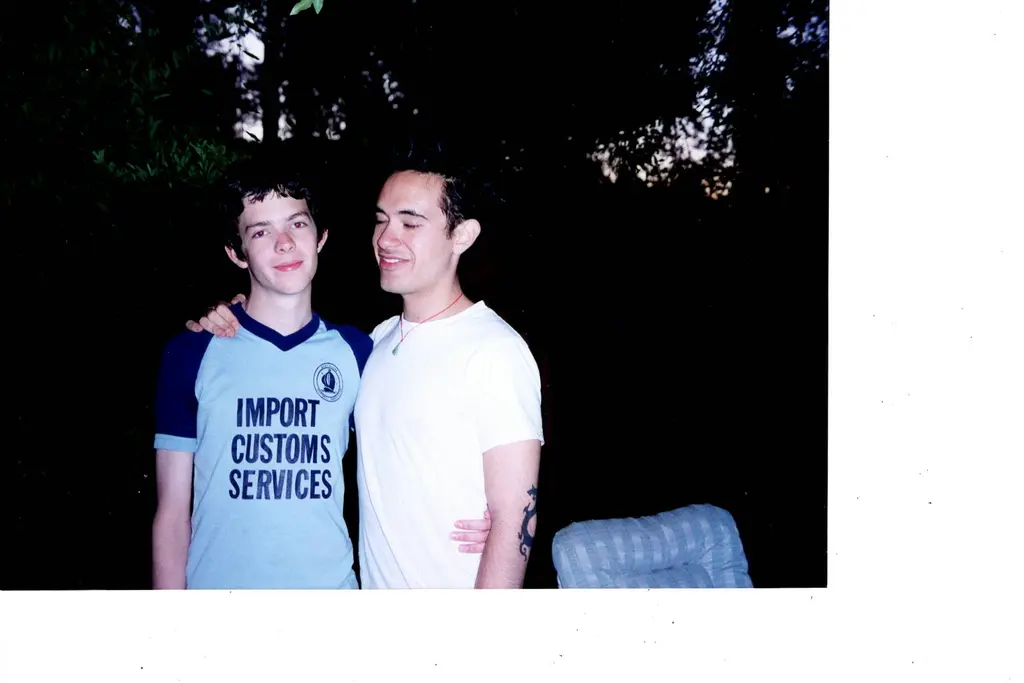

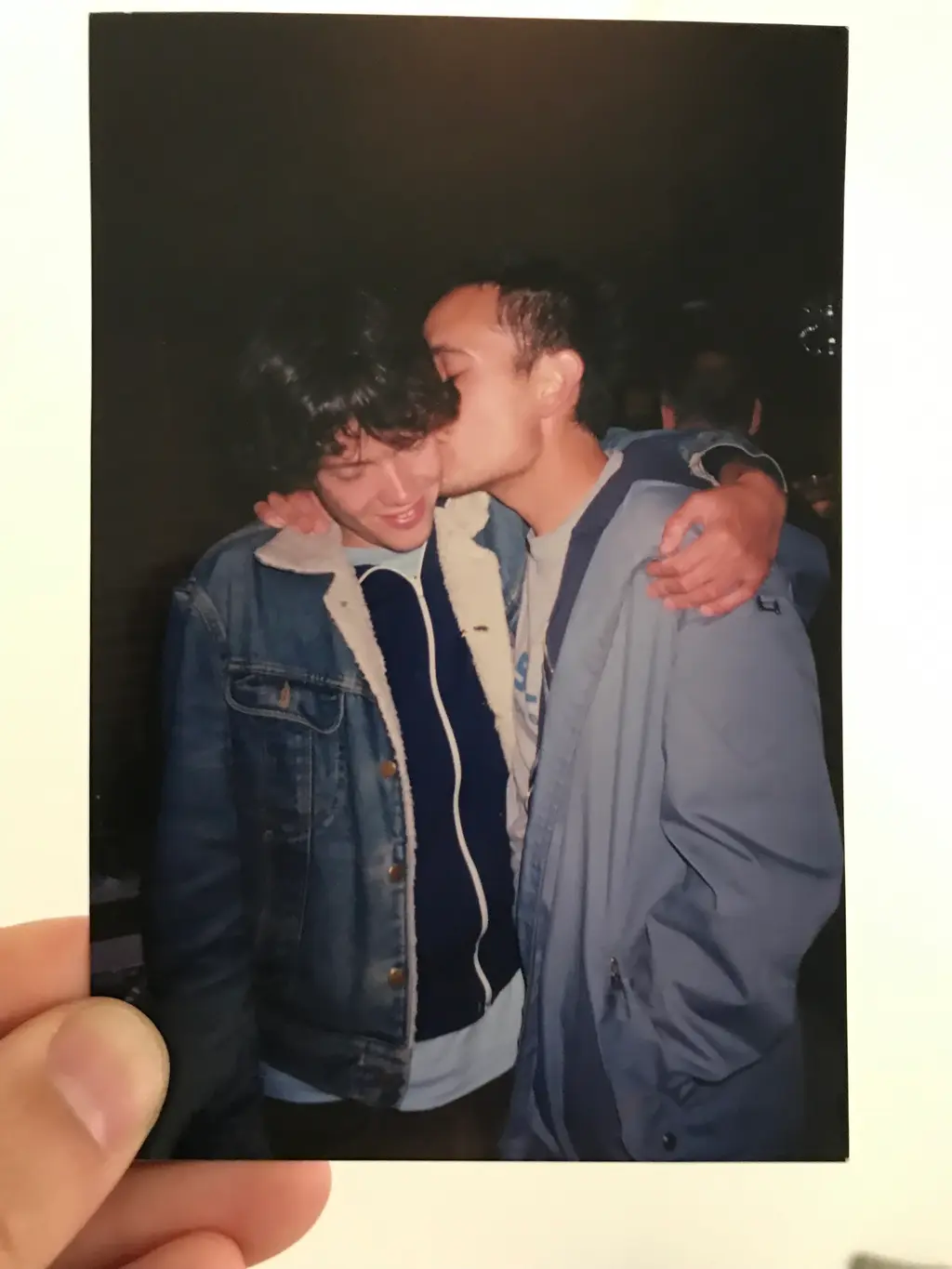

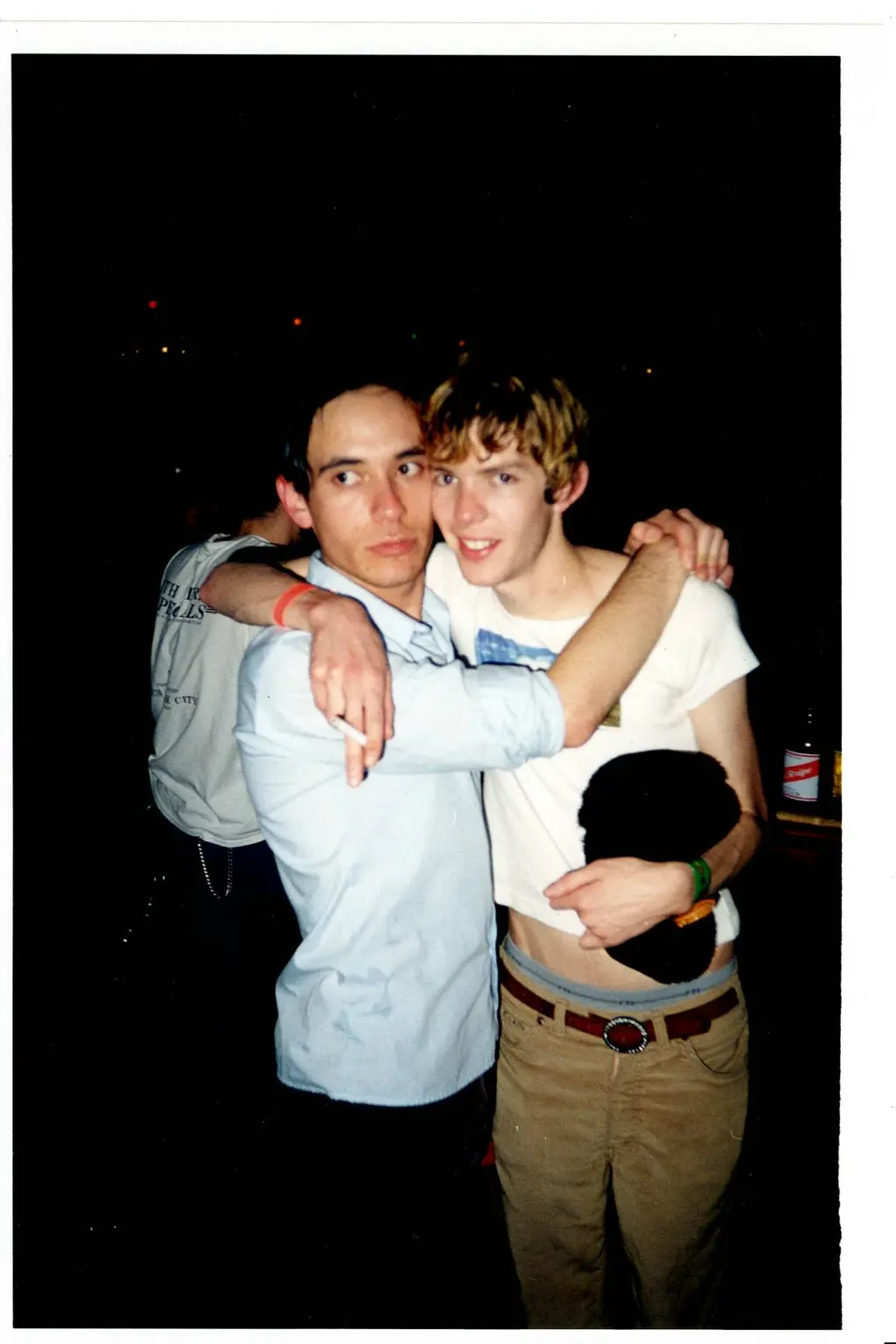

In his new book, Deep House, Jeremy Atherton Lin chronicles the beauty and difficulty of his own long-term relationship against a backdrop of extensive, profound research about the gay men who came before them.

Culture

Words: Alim Kheraj

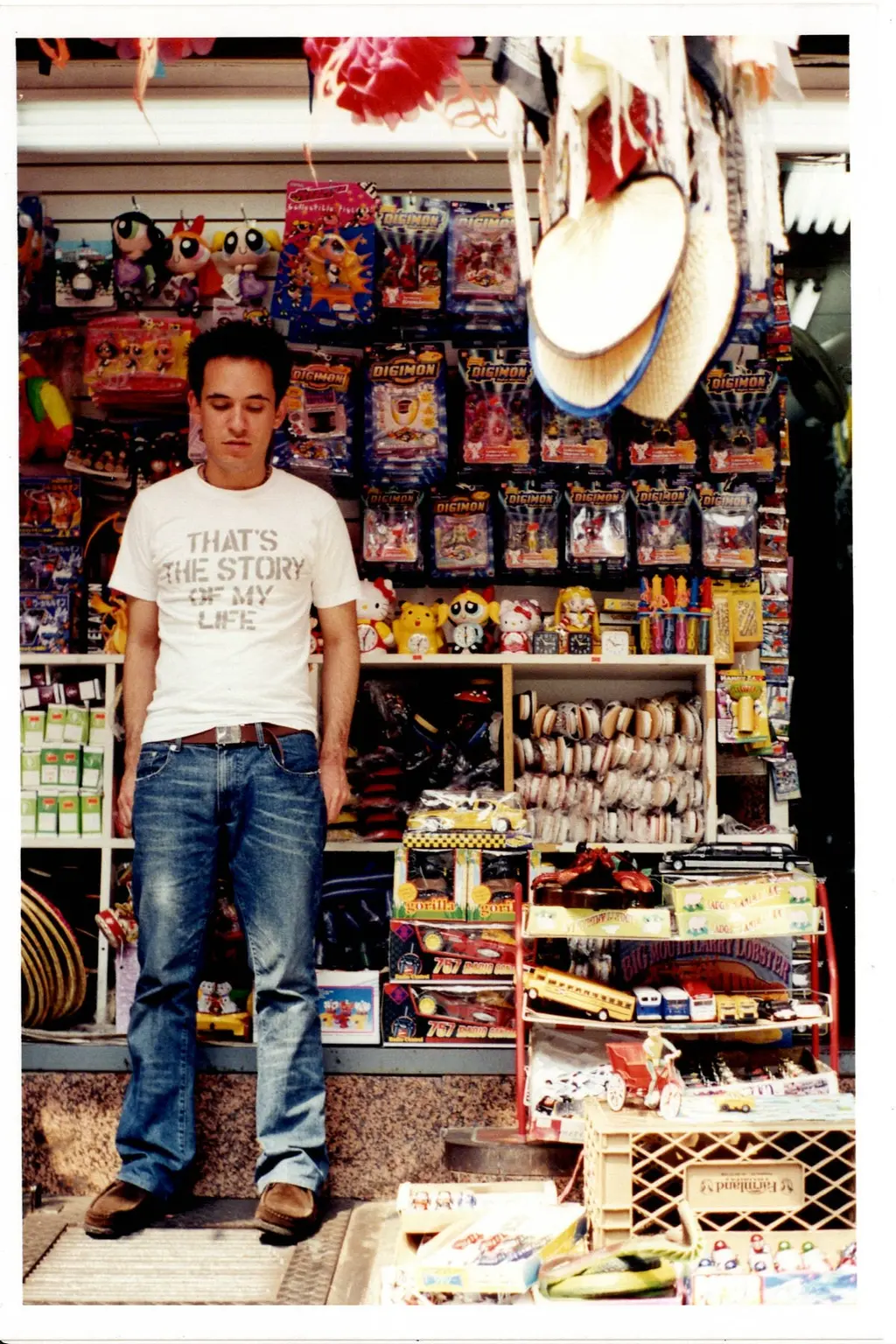

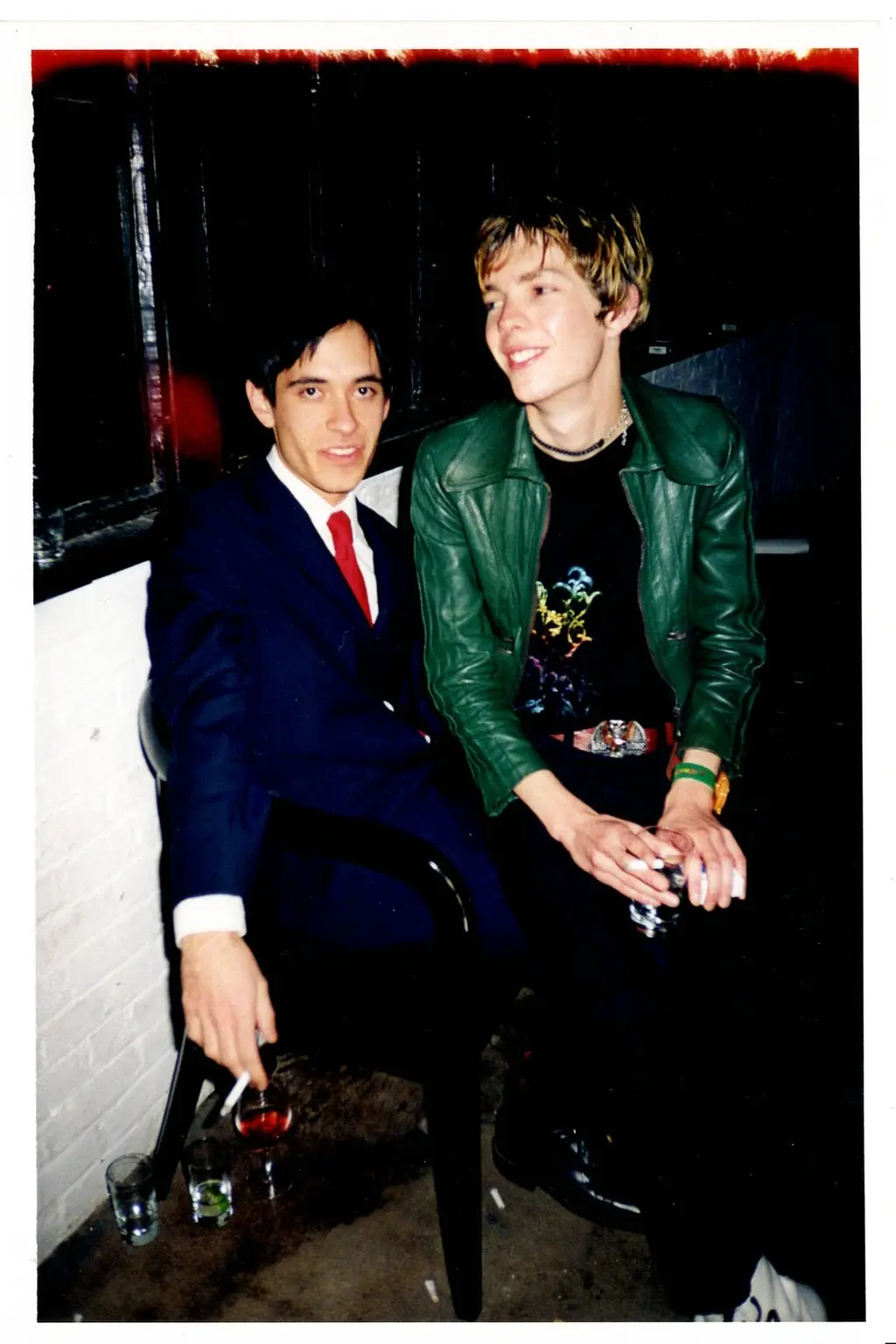

When Jeremy Atherton Lin was writing his second book, Deep House, about his relationship with his long-term British partner (whom he simply calls “Famous”), the California-born, East Sussex-based writer knew that it couldn’t just be about their love story.

“I don’t think I’ve ever felt like any kind of memoir that I write can possibly be isolated,” he explains over Zoom from Brussels, where he is currently on a writing residency. “The notion that our story is not just our own, but is connected to those who came before us, comes really naturally to me.”

This is an approach Atherton Lin took with his first book, the award-winning and brilliant Gay Bar: Why We Went Out. A daring, lubricious amalgam of meticulously researched cultural history, social geography and intimate memoir, that book was a love letter to queer spaces – one resisting the narrative that gay bars are always rainbow-tinted, fan-thwacking safe spaces. Gay Bar was a reminder that these spots can be sleazy and dirty, as well as sites of oppression, disappointment and exclusion.

Deep House follows a similar form, although this time Atherton Lin has his sights set on two interlocking themes: marriage equality and immigration. The book begins in 1996, the year he started his transcontinental relationship with Famous; this coincided with then-President of the United States, Bill Clinton, signing the Defense of Marriage Act into law. This limited the definition of marriage to a union between a man and a woman, denying same-sex couples rights, including immigration rights.

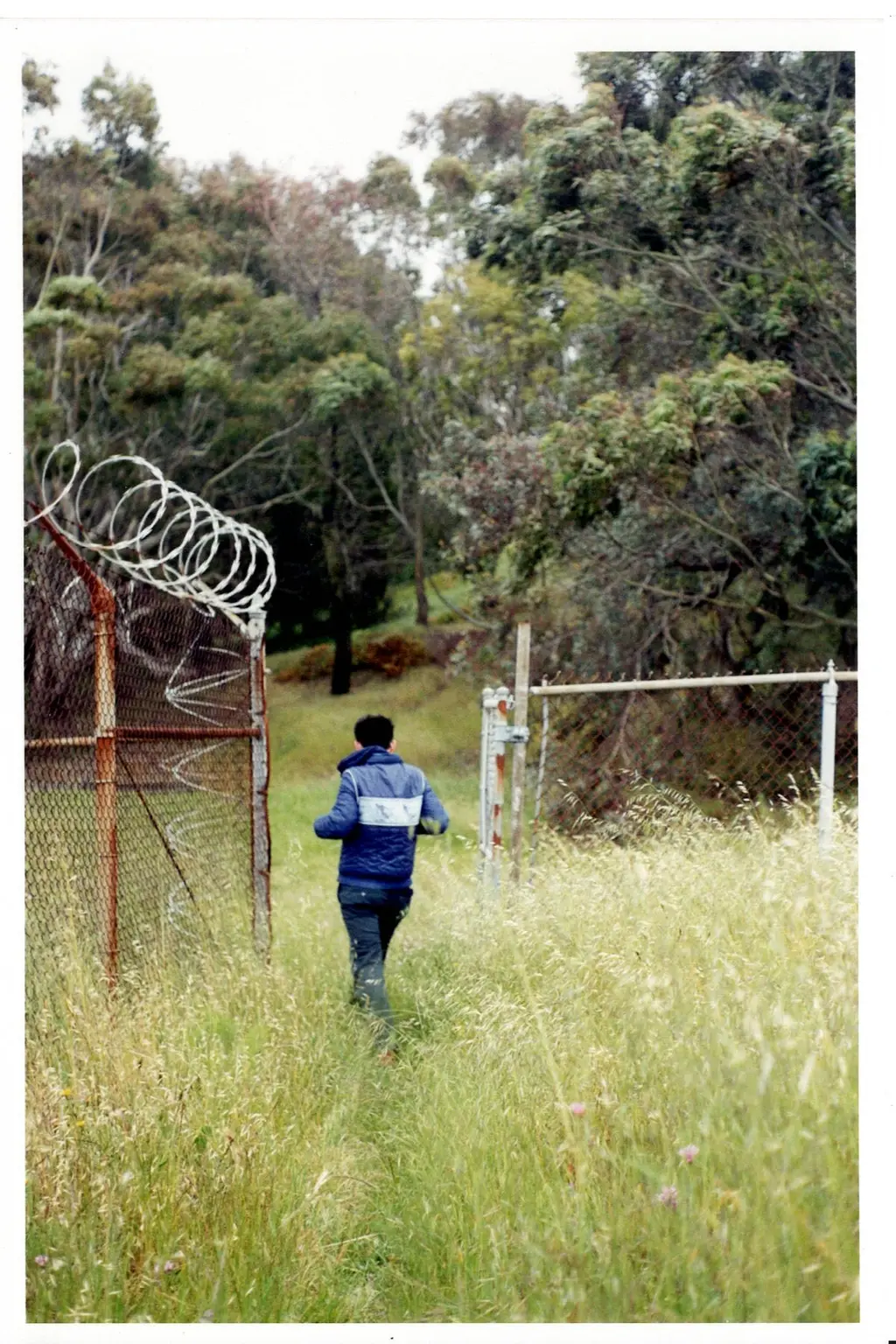

And so the couple were excluded from marriage in both the US and the UK (where same-sex marriage wasn’t legalised until 2013), and Famous eventually settled in San Francisco, where he lived undocumented for nearly a decade. “We were aliens in each other’s countries, because in our own, we remained second-class citizens,” Atherton Lin writes.

To fully explore their story, the author oscillates between his own clandestine, increasingly radical domestic life, and an expansive pre-history of the debate for – and pushback against – marriage equality in the US.

Musky personal passages about threesomes, rimming and anal sex sit alongside the intricately researched tale of eight immigrants executed in Renaissance Rome for their participation in an “aborted [same-sex] marriage ceremony”, or the messy story behind the more recent case of Lawrence v. Texas, which resulted in the US Supreme Court ruling that anti-sodomy laws were unconstitutional. For anyone with even a passing interest in queer history, it’s a seductive approach, and a testament to Atherton Lin’s talents as a writer that he pulls it off.

“The book is about marriage equality,” he says, “but also about different border crossing queers, and the borders of a domestic space or the borders of a household. In this case, [Famous and I] are vessels together as a couple for other people’s experiences in a lineage of gay men, other immigrants and the people around us.”

Why was marriage equality the best lens through which to explore your relationship with Famous?

One of the things that happened when I was putting together the book was that our experience mapped nearly chronologically onto these developments and actions against same-sex marriage in the United States. I was pretty astonished going back and creating the structure of the book that, you know, the Defense of Marriage Act was introduced to US Congress the week that Famous and I met. Of course, we weren’t aware of every step, especially as this was the age before we really used the internet. But we were aware of this political behemoth, and that somehow our experience was becoming relevant to this debate that seemed so abstract and theoretical.

But I don’t think that the book could really be seen as pro-gay marriage. I think it’s a book about two people who have an experience that would be resolved by marriage equality. There’s this structure that’s in tension with your real, messy, complicated, horny and fun private life. And so as the book develops, a case can be made as much for our experience outside of the institution of marriage, this kind of lawless experience in the shadows.

There is so much history and theory in this book. Given how much research must have been involved, how did you go about constructing Deep House?

I use a corkboard, which I jokingly refer to as a murder board. In the case of Deep House, because the overarching structure is chronological, it was about constructing a timeline.

And then in terms of the longer histories, as I began to realise that the book was less about marriage per se and more about crossing borders – national borders, domesticity, the threshold of a home – that became the criteria. Every historical individual, couple or group [in the book] has some kind of aspect of border crossing. I also wanted the book to have this patience with the historical. I was testing how long we can hold the complicated implications of these stories. You might read the results of a given Supreme Court case, but the real mess that’s underneath it is a huge surprise and has massive implications about the way that we create convenient narratives in order to pass through civil rights.

“When we’re being legislated against, I can’t figure out if it’s a squeamishness about sex acts, or if it’s an ignorance about the existence of such euphoria”

There is a real meat to the way you approach writing about sex in the book. How did you land on that kind of language?

There’s a sort of pride in a way that comes through with me sexually, that I don’t necessarily carry with me in my public life. I tend to be quite self-deprecating in my depiction of myself, but I realised that I also needed to include the side of me that’s a bit of an alpha and a bit of a daddy. I also wanted to allow myself to engage in depictions of intimacy that involve mutual forms of surrender, and with that, a sense of overwhelm or mastery that can come from a partner.

It also overlaps a little with Lawrence v. Texas. In that case, there was a projection by the legal team of a wholesome, monogamous couple, when in fact it was actually just two acquaintances who may not have even been copulating in the first place. But the precedent that set was of a kind of homosexual relationship or identity that is respectable, acceptable and worthy of equal rights. It threatens to erase perversion. So with the sex scenes, I was enacting those pervier experiences.

I talk about in the book about how when we’re being legislated against, I can’t figure out if it’s a squeamishness about these kinds of sex acts, or if it’s an ignorance about the existence of such euphoria.

As I was reading the book I was struck by how prescient it was given everything that is happening in the UK and the US when it comes to immigration and the rollback of LGBTQ+ rights. How do you feel about the book coming out in this context?

When Keir Starmer made his U turn in the wrong direction for trans rights, I immediately thought of Bowers v. Hardwick, which was the first significant case challenging anti sodomy laws in the United States. We almost won that case. There was just one justice who was initially going to vote to strike down existing sodomy laws and then changed his mind. And once he changed his mind, he couldn’t change it again. This is what really terrifies me about the etiquette of politics and law. If Starmer hadn’t changed his mind, if he had done the U turn towards truth and respect and liberation and trans equality, we would be in a much better place. I can’t predict things, but if we’re going on the precedent of Bowers v. Hardwick, there would be a motivation for him to double down so that he doesn’t look like he’s flip flopping.

The book reminded me that you can’t rely on the state or legislation for protection or legitimisation. It’s sort of a reminder against complacency.

The terrifying thing is that some of the big swings are coming from the right and yet there’s such a fearfulness on the left, such a reluctance to break free from institutional norms. It doesn’t really feel like my experience of what it means to try and stand up for a fair and just world. I think that’s one of the reasons why I wanted to sit with the mess underneath the surface of a case like Lawrence v. Texas, because it asks: what if the mess itself was allowed to come out into the light? What kind of forms of liberation will come when a fuller accumulation of experiences can be brought to light? I don’t think my books are written for fence sitters or someone who might suddenly want to engage in the cause of gay liberation. But I do think that this book might contribute to the discussion that we can be worthy beings, even if we’re filthy motherfuckers.

Deep House is out now, would you believe. Get your hands on it here.