Life as a 30-year-old designer with chronic illness

Mental Health Diaries: Book designer Geoffrey Bunting spotlights the mental strain that comes with living with chronic fatigue syndrome.

Life

Words: Geoffrey Bunting

Each year, one in four people will struggle with their mental health in some way. But you don’t need statistics to realise the true extent of the problem. You perhaps only need to speak to friends and family, or even look inwardly, to notice that our collective mental health is in freefall. As we figure out how to heal from the tragedies of the pandemic, awareness has never been more important.

It’s not all doom and gloom, though. Running parallel to the rise in mental health issues is a growing desire to open up about the things we usually bottle up. Slowly but surely, stigmas are being smashed, taboos are being lifted, and more people are finding the courage to speak out.

THE FACE’s new series, Mental Health Diaries, is only part of the conversation. By laying the realities of living with various issues bare, we hope to not only encourage understanding and empathy towards those with stigmatised conditions, but also inspire people to reach out to others and seek support. Most importantly, we want everyone to know that they’re not alone.

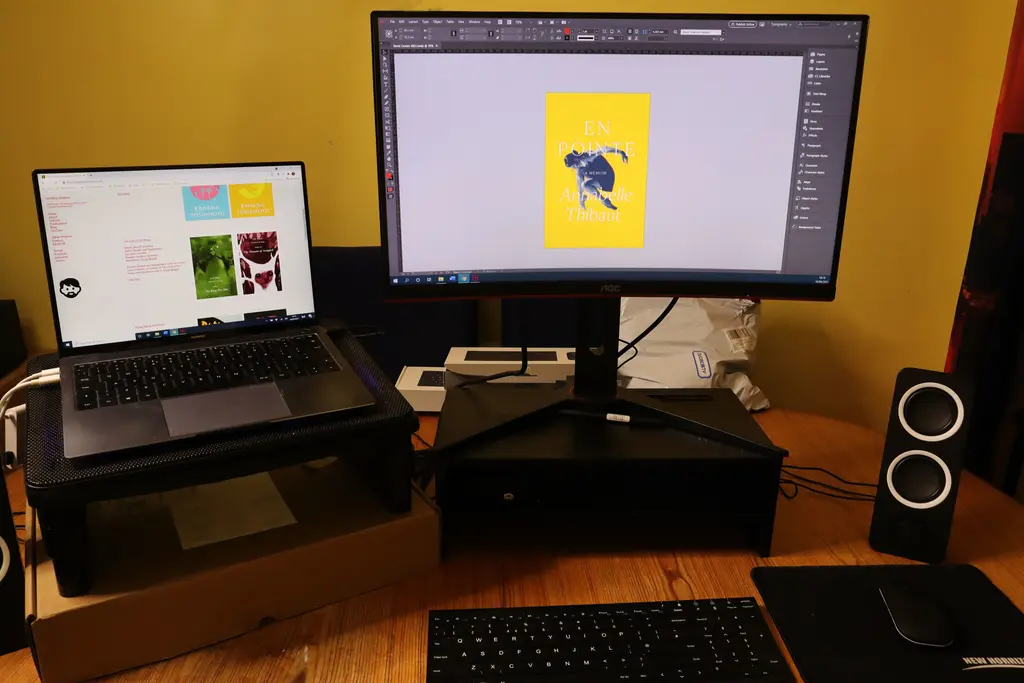

My name is Geoffrey Bunting. I’m a 30-year-old book designer and writer from Norfolk. I’ve lived with an undefined arrythmia (abnormal heart rhythm) since I was 11 and was diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS/ME) in 2015. There is no monolithic way to describe chronic illness. CFS is a blanket diagnosis thrown over a range of conditions by doctors that don’t understand them. How we experience them is highly individual. I suffer from daily intense fatigue, cognitive issues, headaches and migraines, and pain. As a naturally productive person, I spend a lot of time feeling frustrated as a result and, undeservedly, angry at myself. But it affects everyone differently. The only universals appear to be that depression and anxiety are so common we could regard them as symptoms in their own right, and that medical professionals have mistreated the vast majority of us.

5:00AM: I wake up and take a bisoprolol, a beta blocker typically used to treat high blood pressure. Everyday illnesses hit us differently. In 2019, a virus raised my resting heart rate from 55 to 85 for nine months. In that period, I woke up in the early hours with a heart rate over 120 so often that anxiety made it a habit to wake up at 5am. Now, I worry that if I take my pill later, when I’m fully awake, it won’t work. It’s stupid, but then so is anxiety.

7:00AM: My cat paws at my shoulder, demanding food. I let the blue light of my phone wake me up, switching between Twitter, The Dots and Instagram. Eventually, I get up.

7:45AM: A cereal bar for breakfast. Sometimes I’d like more, but doctors love to tell me I’m fat instead of listening to my health concerns. My meal plan tells me lunch is tofu, greens and black beans.

8:00AM: I stare at people on my phone who have achieved more than me. After six years, I still can’t understand why I can’t keep up. I spent much of last week worrying that I wasn’t really ill because I didn’t feel as bad as usual, only for two days of intense migraines and fatigue to reassure me. We have names for our physical symptoms. But we don’t talk about chronic doubt: how we’re forced to normalise our disabilities so much that we don’t believe in them.

9:30AM: I have a choice: a short walk or work. It is common in chronic illness for symptoms to be delayed. If I work, my headache will worsen this afternoon; if I walk, it might not be possible for me to make dinner. I have several ongoing projects, so I can’t afford to exercise. I open a Word document and stare at the floaters in my eyes. I move things around in InDesign and call it progress. Things that used to take a few minutes now take hours. It’s demoralising.

10:30AM: Brain fog is one of the most common symptoms of chronic illness. It causes problems with concentration and focus, blocks creative thought and impairs memory. I’ve forgotten what I’m having for lunch and panic that I don’t have what I need. Yesterday, I forgot to pick up my medication. It’s a 3‑minute drive to the pharmacy. The doors are heavy and hurt my wrists. There was nowhere to sit. While I waited, I had two heart palpitations, which made me freeze with the anxiety that each might herald the onset of arrhythmia. It distracts me and I speak too much. Everything in my life is about economy: each word I use represents energy I lose later. It’s hard and it’s depressing that people don’t notice. They just think I’m curt. I’m constantly folding myself into uncomfortable shapes, because we built this world around able-bodied people.

12:00PM: Lunch. I eat a bowl of cereal. I’m too tired to prepare anything. I have a little lunchtime cry, like Emma Thompson in Love, Actually when Alan Rickman gives her a Joni Mitchell CD. Some people take micro-naps, I have micro-cries.

12:15PM: I play video games for a while. My brain fog feels like I’m wearing glasses and can only focus on a smudge on the lenses. I’m hoping it might improve this afternoon. But when you’re ill, hope is often just disappointment that hasn’t happened yet.

2:00PM: I’m beating myself up for not getting back to work. The palpitations have rattled me and I’m scared to move. I used to cycle 90 miles a week. Now, I can’t get on a bike. I ignore that and compare myself to able-bodied people instead. I move everything back in InDesign.

3:30PM: I walk around the garden. The grass is too long. More palpitations – it’s one of those days. Tomorrow, I’ll have another choice: work, walk or cut the grass.

5:00PM: My day ends as others begin. Neighbours get home from work and launch into projects or entertaining their children, while I need to rest after I bathe. Fatigue hits me in waves throughout the day, some gentle and some rough. I’m in a dip. I’m paying for extra words I spoke earlier. I don’t know whether I’m more upset at myself for making a fundamental mistake or my illness for making this way. Sometimes it’s easier to blame myself.

7:00PM: Video games again. I struggle to watch TV or listen to music. I have to be doing something. When I was able to work, this natural inclination to productivity was a great quality. Now, it’s a constant painful reminder of how little I’m capable of. Playing games lets me feel like I’m an active part of something rather than a passive observer. I still admonish myself for doing “nothing”, but this is what I need to do right now.

9:00PM: I’m hit by a burst of energy. Not enough to make me productive, just to stop me from sleeping. The irony isn’t lost on me that difficulty sleeping is a major symptom of fatigue disorders.

10:00PM: I brush my teeth and go to bed. I watch Korean dramas. They visualise every emotion, so I don’t have to work out how people feel. This is how I start saving energy for tomorrow.

12:30PM: I switch to something I’ve seen before. Boredom is the only way I get to sleep. I’ve made it through another day. Today, surviving felt a lot like not living.

Q&A

What’s the number one misconception about chronic illness?

That we’re lazy. Doctors tell all of us how to live: to eat well, exercise, etc. But many chronic illness patients did all that, worked hard and still got ill. That frightens people. It’s easier for them to believe we’re doing something wrong or not doing enough than to recognise that it could happen to anyone. I can pinpoint the exact time and date I got sick (chronic illness can have a gradual or sudden onset in different patients), because it happened that fast. But people don’t understand that. So, they dismiss us, call us lazy and brand us a burden. I didn’t ask for it, I’m not revelling in it – I have a difficult life.

What’s the most useful coping mechanism you use?

I’m not what people call a coper. I hope to one day find some relief (beyond booping my cat on the nose). But at the moment, I’m still coming to terms with my life. I lived with my family for a long time and, though I still live in my family home, I only recently gained the independence I needed to interrogate how I feel. The only thing I can advise is that people find something they feel capable of that can occupy their long periods of downtime. For me, it’s video games. For others, it might be films, reading, journaling or doing that thing from 2020 where everything is cake.

What would your message to fellow sufferers be?

Able-bodied people love to point out what we can’t do, while they also criticise us for using the word “can’t” to excuse ourselves from dangerous and/or difficult situations. They force us to doubt ourselves by telling us that disabled people can’t be polite, can’t be intelligent, can’t be happy. But we can. Achieving things, living our lives and refusing to let our disabilities jade us doesn’t make us less disabled. Nor does being angry or struggling mean we’re adhering to the stereotypes enforced upon us by people with no idea what we’re going through. The Department for Work and Pensions refused me help because I achieved a master’s degree in 2020, despite it being even more of an achievement for someone with my level of disability to do so. I’ve gained publications, edited a novel, designed books – all of which are as much a part of my identity as my very real disability. We’re human beings. That hasn’t changed. We deserve to feel everything we do without being policed by ignorant people. That includes feelings that might make able-bodied people uncomfortable like anger, frustration and depression.