Meet the changing face of horse racing

As the number of women jockeys grows, a new subculture is shaping the horse racing industry.

Life

Words: Georgie Lane-Godfrey

Photography: Clémentine Schneidermann

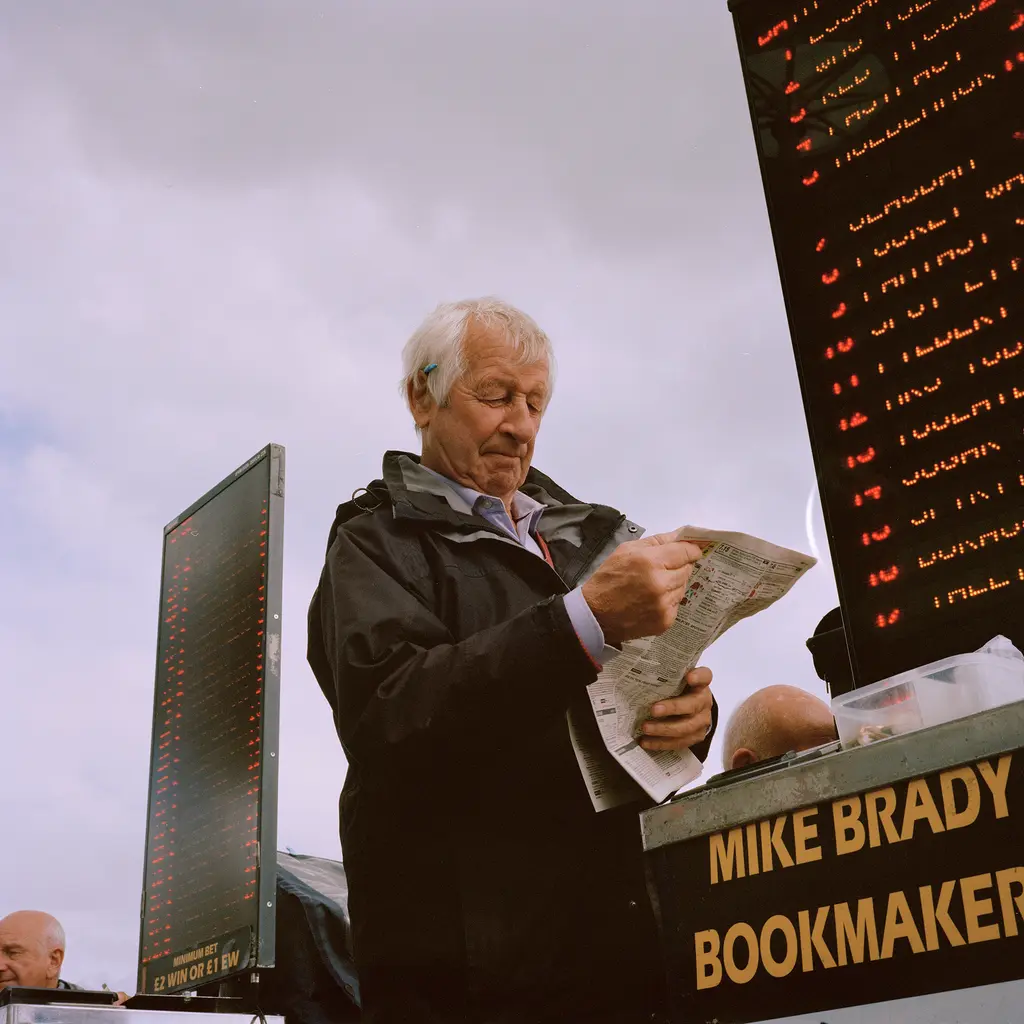

Friday night at Bath Racecourse. A pair of women clad in summer dresses totter past security arm-in-arm. Bare-ankled boys in blazers watch them surreptitiously over the brims of their plastic beer cups. The flap and crackle of newspapers sounds as the weathered, flat-capped faces of seasoned race-goers check the runners in The Racing Post. A cheer goes up at the entrance as a stag-do walks in, the groom wearing trousers that make him look like he’s riding a leprechaun. The balding steward waves them off jovially in a thick Bristolian accent. Up in the boxes, there’s laughter from the owners waiting to watch their horses run.

The racecourse is packed with punters from across the social spectrum. But while the love of the so-called “sport of kings” might be a great equaliser, the industry itself hasn’t been the most level playing field. Two years ago a study by Oxford Brookes University found that many women working in the sport reported feeling patronised and unwelcome in the old boys’ network that is British Racing. Others talked of bullying and sexist behaviour on yards (as racing stables are known in the industry), frequently written off as “banter culture”. One of the main complaints, however, revolved around lack of opportunity – women not being taken seriously and denied both rides and promotions on the grounds of gender.

With thousands of pounds in winnings at stake, it’s easy to understand their grievances. The richest prize in UK flat racing is The Derby, with a pot of £1,625,000 for a race lasting just over two and a half minutes. In jump racing, where distances are further and the risk of injury higher, prize money is, ironically lower – even the Grand National offers a total pot of £1 million. Jockeys take a cut of those winnings, ranging from seven to nine per cent. Top jockeys will ride thousands of winners over the course of their career, often resulting in an impressive income. The legendary Frankie Dettori has ridden over 3000 winners, earning him an estimated £2 million a year and an overall net wealth of some £14 million.

But 2019 is a different story. Currently women outnumber men entering the racing industry at a ratio of nearly 70:30. Of course, not all of these women will become jockeys. There are a variety of career paths in racing, including becoming trainers, grooms, secretaries, judges, stud managers, stewards and starters. But for many attending one of the two racing schools in the UK in Doncaster and Newmarket, a career as a jockey is the ambition, meaning that numbers are growing. Here at Bath, in the first race, five of the seventeen runners have a female jockey onboard – two of them place in the top three finishers.

One of them is Sophie Ralston, who made headlines earlier this year when she publicly addressed her lack of opportunity to ride as a jockey. “In September I turned 26, so I couldn’t ride as an apprentice anymore,” she says. In racing, trainee flat jockeys are known as apprentices, and are given a weight allowance when they ride in races against professional jockeys in order to compensate for a lack of experience and to ensure they still get rides off trainers. “I’d won the Apprentice Training Series earlier that year – a group of races for specifically for trainee jockeys – which had given my career a real boost, but then when I went professional.” This development is significant. Apprentices are given a 7lb weight allowance at the beginning of their careers, a move designed to provide an advantage to their horse in return for the potential disadvantage of having a relatively inexperienced jockey on board. The allowance decreases with the number of wins a jockey achieves, but at the start of their career, a jockey could weigh in at seven-and-a-half stone instead of the eight stone minimum thanks to their claim.

A seven-pound claim makes apprentice riders attractive to trainers, so without it, a newly professional jockey can struggle. “I suddenly hit a flat spot when I went professional,” says Ralston. “So I came up with the idea of writing an open letter to The Racing Post to directly ask trainers for rides.” This constituted a risk – most jockeys will go through a slow period during their career in which they won’t be offered many rides by trainers, for example when coming back from injury or going freelance. Openly talking about it was set to raise eyebrows. “It was a risk,” she admits, “but it worked. Now I’ve had a really good start to the season with five wins. I’ve never clocked up so many early on.”

Clearly things are changing as women carve out their own identity within racing. Much of it is based on a camaraderie built in the weighing room and changing rooms. Not so long ago, the latter would be largely empty save for one or two women slipping into their racing silks in silence. Indeed, jump jockey Lizzie Kelly has talked about how boring it can be for a woman, she herself preferring to wait in the men’s changing room rather than sit alone.

Harriet Tucker

Now, though, “I’ve massively seen the difference in the number of women who would be in the weighing room with me,” says Hayley Turner, the 36-year-old commonly held to be the best female jockey of all time. “Before it was usually empty… Today, it’s a fun place to be.”

“I can’t remember the last time I was the only woman in there,” agrees Josephine Gordon, affectionately known in the industry as JoGo. Not only a Group One-winning jockey – the most prestigious level of race – Gordon also gained the coveted Champion Apprentice title in 2016, a victory which secures any jockey’s reputation in the industry. She’s only the third women to ever claim that title, with Turner being one of the other two.

“Hayley was the trailblazer – she started it off for us girls,” she says. “She was my idol, and my dream was always to race against her. We get on really well now. I know that if I ever needed advice or help, she’d be there.”

Turner explains that she never had the benefit of a mentor. “People always ask if I had a favourite jockey, but there were no girls I admired massively. So helping the girls riding now is important to me.”

But while the community are willing to help each other, they all share the belief that women shouldn’t receive special allowances and are vocal about wanting recognition on their own terms. It’s a fine line to tread, as proved by the popularity of initiatives like The Silk Series, a £150,000 race series for female jockeys across 15 British racecourses.

“I think we should be proud we can have girls’ competitions because there’s so many of us now,” says Sophie Ralston. “I’d love to win it too – there’s £20,000 to the winner!” she laughs. When you consider that the average salary for a jockey is £26,000, her hunger to win is understandable.

Hayley Turner

Equally, discussions over introducing a quota system to ensure the number of female jockeys in each race have been less well-received. In fact, each of the women I speak to vehemently oppose it. “If women want to get into racing, there’s plenty of help. It’s quite accessible now,” says Turner. “But they shouldn’t just get rides for being women. You’ve got to be good enough as well. Riding is dangerous, so think of the safety element. You can’t just allow women in for the sake of numbers.”

In fact, the level of sacrifice is the same regardless of gender. Race riders have to work 13 out of 14 days over a two week period, a necessity not only because of the full-time nature of caring for animals, but also the shortage of stable staff. On work days, they’re expected to be on the yard for 6.30am to start mucking out stables, as well as grooming, feeding and exercising a minimum of three horses all before lunch. What’s more, it’s physically gruelling work. All jockeys must have a licence to ensure they have sufficient skill, knowledge and fitness to race. But to receive their licence, they must pass a high-intensity fitness test at the racing school which comprises achieving at least a level 13 on the bleep test, and hold a series of positions. These include balancing in a squat on wobble cushions for at least 90 seconds, maintaining a lowered press-up position for a minimum of a minute and holding a plank for at least three minutes. Only three jockeys in history have ever achieved 100 per cent.

And aside from fitness, there’s also the need for a high pain threshold. Case in point: Harriet Tucker. The 23-year-old jockey rode Pacha du Polder to victory in the Foxhunter Challenge Cup at last year’s Cheltenham Festival, the jumping equivalent to Royal Ascot.

Josephine Gordon

“We were coming from four furlongs out going down the hill,” recalls Tucker. “I started pushing him forward to jump the last, and as I came over my shoulder dislocated. I could feel the ball of my bone rolling around in my arm. Normally I would have stopped riding, but the adrenaline kicked in so I just kept driving without my whip. I remember looking across at [rival jockey] Sam [Davies-Thomas] and thinking: ‘He can’t beat me!’ So I just kept screaming and pushing and praying.”

Tucker pushed to finish line using “hands and heels”, a method used by trainee jockeys to encourage a horse to ride faster that uses only your hands to drive the horse forward and heels to kick on. Most importantly this finish doesn’t use a whip – a key tool for any jockey wanting to encourage a horse to run on when it’s starting to run out of steam. Hands and heels finishes are, quite simply, exhausting. Imagine crouching in a squat, staring at the ceiling, clicking your heels together and pumping your arms up and down – all while having a dislocated shoulder and trying to win a high-profile race.

Tucker won, with Davies-Thomas in second place.

After that #HardyHarriet started trending Twitter. Stoic to the end, Tucker shrugs at the accolade. “It’s just in my head not to be weak. To be that stronger person. I didn’t want to be weak so I told myself to get on with it. All jockeys are tough. You’ve got to be in this game. No pain, no gain,” she smiles.

Despite the journalistically-juicy narrative, it’s a story that flew under the radar in the media. “All of a sudden, people were saying I should have been up for BBC Sports Personality of the Year and there should have been more coverage of it.”

But for female jockeys, media attention is a double-edged sword.

“There was a feature the other day on The Top Ten Female jockeys and how many winners we had ridden in our careers,” notes Josephine Gordon. “Why are we still getting compared and pushed against each other when we’re taking on the boys as well? I remember when I started doing well, they made a big thing out a rivalry between me and Hayley, and there’s not at all. When one of the girls has a winner, we all cheer.”

Sophie Ralston

While female jockeys might be supportive of each other, punters are a different breed. During our interview, JoGo pulls out her phone to show the countless abusive messages she receives on social media. They are almost exclusively from men.

“I woke up to one really nasty one this morning,” she says, opening it up for us to read. “He’s actually sent me a few.” The text is as sadly predictable as it is shocking: “u r a useless cunt with no future in d game. U will end up suckin cock to pay da rent.”

When I ask whether she reports them, Gordon shrugs. “There’s no point. Majority of the time I just ignore it and don’t reply. But sometimes when I’m in a really bad mood, I will just have a little niggle back just to get the anger out. But very rarely. You have to be hardened to it in this game.”

This kind of abuse appears across both flat and jump racing.

“When I rode Monsieur Gibraltor at Ascot, one punter was rooting for me the whole way. Then once I was unseated [the term for being thrown from a horse], he said he hoped that I snap my neck and die,” says Tucker with an incredulous laugh. “I was angry at the time. But if they want to message me absolute rubbish, they can crack on. It’s their time they are wasting, not mine.”

Both Gordon and Tucker, however, are quick to point out that abuse affects jockeys regardless of gender. “The boys probably get it even worse,” thinks Gordon.

“It’s the type of thing which would affect your mental health if you got quite a lot of it,” adds Tucker. “But to be honest, jockeys do get abuse all the time.”

“Most of the time us girls laugh about it together,” concludes Gordon, with a smile. Tucker grins and agrees that it takes more than a few hideous male trolls to take down a tough, fit jockey.

“I spoke to one of my friends and she was like: ‘Oh yeah! I got a message off him the other day.’ It’s like a club!”

RACING EXPLAINED: A GLOSSARY

Allowance, the weight concession inexperienced riders are given to compensate

All-weather Track (AWT), an artificial racing surface which allows for racing throughout the year

Apprentice, a trainee jockey connected to the stable of a licensed trainer

Apprentice Training Series, a series of races for flat trainee jockeys who have ridden less than 20 winners

Ascot, a British racecourse

Champion Apprentice, the annual title awarded to the apprentice jockey who rides the most wins in a season

Cheltenham Festival, the premier meeting at the home of jump racing

Classics, a group of historic major races for three-year-old horses in the flat season, including The Derby

Colours, the jacket worn by a jockey to represent an owner

Conditional jockey, a jump jockey aged under 26. Permitted to carry less weight to allow for inexperience

Colt, a young male horse

Draw, the position a horse is allocated in the starting stalls

DNF, short for Did Not Finish

Filly, a young female horse up to the age of four

Furlong, metric in racing which equates to 220 yards

Gelding, a castrated male horse

Green, used to describe an inexperienced horse

Group One, the highest level of race

Handicap, a race in which a horse each carries a different weight to even out their chances

Hands and Heels, a race in which a jockey encourages the horse without the use of a whip

Licence, the permit needed to take part in any aspect racing

Listed, a class of race just below a Group of graded quality

Place, to finish in the top four positions in a race

Push, ride a horse to go faster

Pulled-up, when a horse drops out of a race and does not finish

National Hunt, jump racing

Racecard, the programme of races for the day

Racing Post, British daily racing newspaper

Ride a finish, to push the horse forwards at the end of a race

Royal Ascot, a week of special races at Ascot Racecourse attended by the Queen

Starting stalls, a mobile machine from which horses emerge to ensure a fair start

Silks, the racing colours worn by jockeys

Trip, the distance of a race

Unseated, when a jockey falls from a horse

Weighing Room, the place where jockeys are weighed to check they are carrying the correct weight both before and after a race

Yard, name for a group of stables

QIPCO British Champions Series showcases the finest flat racing, with eight Series races taking place during Royal Ascot this week. For more information, go to britishchampionsseries.com