Music of African origin is having a moment – now festivals are celebrating the wave

Once the subject schoolyard taunts, African heritage is now a badge of pride among the UK diaspora. The music scene is driving the cultural shift.

Music

Words: Yomi Adegoke

Photography: Samuel Martins / @maimagazine

“What the hell is going on in Portimão?” a local tweeted at the start of the Portugal based Afro Nation festival. “It’s a thousand Nicki Minaj and Drakes here!”

The startled tweeter was referencing the unofficial dress code of Afro Nation, which saw the Portimão beach in Portugal become a blur of neon bikinis, hand held fans made from kente cloth, diamante studded mesh dresses and most notably, melanin. The four day event which saw over 20,000 predominantly Black British revellers rock up to the Algarve, is arguably the first of its kind in terms of ambition and scale.

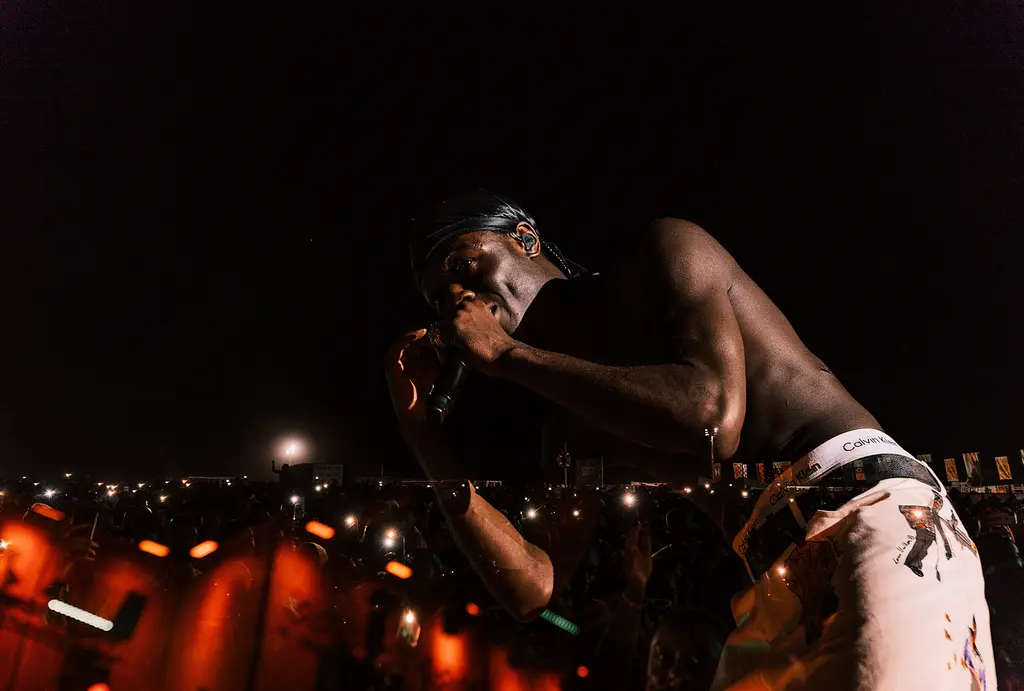

With a line-up that boasted Wizkid, Busy Signal, Davido, Stefflon Don, Burna Boy and as a surprise act, J Hus, many believed it was too good to be true. An anxiety around the organisation of black run-events saw it soon rubbished as “the black Fyre festival” on social media and hiccups regarding the line-up (NSG dropped out, IAMDDB said she was never performing, despite being billed) saw it instantly compared to white-run, “more professional” urban music event outfits like Fresh Island before it had even begun. But as the unforgettable first night unfolded to much fanfare and FOMO inducing Insta-stories, it was clear it would not simply exceed expectations but shatter them. As the events host Eddie Kadi said of Fyre Festival comparisons: “I’m here to be the extinguisher.”

Since Afro Nation’s vindication, there has been an unshakeable sense of triumph, not just because it was an impeccably run event, but at what its existence means more broadly. Artists like Burna Boy and Mr Eazi playing Coachella and Stormzy headlining Glastonbury provoke pride, but performing at white-dominated events is only one part of the journey. This year has seen the diaspora carve out its own spaces on the festival landscape in a way never seen before; the logical conclusion of continued chart takeovers by UK rap, grime, Afrobeats and Afrobashment. With Dave’s UK number one album, Burna Boy’s reaching the Billboard 200, the success of Afro B’s Drogba stateside and Universal Music launching a Nigerian division, it’s a great time musically – something we are finally seeing reflected at large events.

Afro Nation 2019

This year has seen not just the launch of Afro Nation, but One Africa Music festival which will take place in London’s SSE arena, with Stefflon Don, Burna Boy, Tekno, 2face. Summer saw The Ends festival in my hometown of Croydon, whose stellar line up included Wizkid, Maleek Berry, Wande Coal, Kranium, Teni, Sneakbo, Damian Marley. Despite fears of violence, it too went off without a hitch. The three day, 15,000 capacity festival took place in the locally-beloved Lloyd Park, during the best bit of the British summer. The year before, Wizkid also headlined the Afro Republik festival at the O2 with support from the likes of Tiwa Savage and UK artists like Not3s and Yxng Bane. Afrobeats fans will know that the O2 has always been the stomping ground of heavyweights such as D’banj, R2Bees and Wande Coal. Smade (the brains behind Afro Nation) was the promoter of Wizkid and Davido’s sold out O2 shows, and took his years of championing music of African origin and exploded it onto the Algarve.

But this sense of triumph goes beyond well-orchestrated, well-received events. Genres like Afrobeats and Afrobashment are responsible for many second generation immigrant Brits finding pride in the identities they were shamed for. For too long, so little in Britain has been promoted about the African continent beyond Comic Relief adverts. An African identity is something you were often teased for, as most who grew up in the UK know too well. “We can now say ‘ehen’ and ‘ah-ahn’, in public without being embarrassed,” Eddie Kadi said to a whooping crowd on the final night of Afro Nation, in reference to the exclamations often made by Nigerians. He split the crowd in two, having each side chant them.

Afro Nation truly felt like one unified nation too, founded on #BlackExcellence and good vibes. Not only was fear of fallouts unwarranted, but it was a welcome reprieve to the so-called “diaspora wars” we so often see online, a hangover from the secondary school experiences of many black British youths. Whether it be lighthearted debates between African and Caribbeans around the pronunciation of “plantain” or more serious divisions that quickly turn into dangerous stereotyping, anything can set off the near-daily Twitter debates that leads to friction and factioning. In it, there are few allies: Africans vs Caribbeans, West Africans vs East Africans, Nigerians vs the rest of the diaspora. Black Brits rally together when being attacked as a whole – for instance, when many African Americans were incensed about the casting of black British actress Cynthia Erivo in the role of Harriet Tubman, or when black Brits and Africans worldwide staged a coordinated drag of Spike Lee’s portrayal of an African-British character in his show She’s Gotta Have It which was offensive to all. Even joyous occasions such as Beyoncé blessing us with new music are marred by them – the release of her Lion King album was dominated by criticism of what some saw as the snubbing of musicians from East Africa, in which the film is set.

But historically, to quote Madonna, music makes the people come together. The “Afrobeats vs Bashment” raves I used to go to as a teenager were about dance-offs, not division. Friction on social media between these groups rarely translates offline, and certainly not at events. Afro Nation in particular showcased the symbiotic relationship between various black countries and communities, who borrow from each other sonically and are inspired by each others sounds. It is unsurprising that one genre that dominated the event, Afrobashment, is the love child of Afrobeats, bashment, dancehall and UK rap.

The best part about it’s success is that in a world that so often expects the black community to seek acceptance from wider, whiter society, Afro Nation was about us validating ourselves. To remind us that well-run events are not the preserve of white companies, that supporting each other goes a long way and that when it’s all said and done, we all simply want to get lit to each others music, in sun and safety. With the Ghanaian iteration around the corner in November, I for one plan to do so again.