Working Men’s Club: the Heavenly sound of young Yorkshire

Syd Minsky-Sargeant is on a teenage mission from Todmorden: to make hometown music that reaches up and out of the Calder Valley – and it’s electrifying the UK indie scene.

Music

Words: Craig McLean

Photography: Neil R. Thomson

“Trapped, inside a town, inside my mind /Stuck with no ideas, I’m running out of time /There’s no quick escape, so many mistakes, I’ll play the long game /This winter is a curse , and the valley is my hearse, when will it take me /To the grave?” – Valleys by Working Men’s Club

Trapped inside his cramped bedroom, Syd Minsky-Sargeant of Working Men’s Club is showing me the “piece of shit” kit he used to write his band’s self-titled album: a Korg Volca FM digital synthesiser, a 1986-vintage Roland Rhythm Composer TR-505 drum machine and MIDI sequencer, and a MacBook Pro laptop.

Stacked up to the low ceiling on slanted shelves are synths, keyboards and tangles of wires. Four guitars hang on the walls above his unmade bed. Socks explode from half-opened drawers. Out the small window, a view down into the valley he’s called home (and, more recently, to quote those lyrics, a hearse) for 18 of his 19 years.

This home studio, in his mum and stepdad’s house on a hill overlooking Todmorden in West Yorkshire’s Upper Calder Valley, is where Minsky-Sargeant “locked myself away” in the dreary months of late 2019, writing and writing and writing “All my friends had gone away to uni. I was in and out of touring, and it’s so dark here in winter,” he rattles in his flat Yorkshire accent. “So I was just trying to find ways to keep myself sane, really.”

Valleys was one of those sanity-saving tunes. Hammering yet sinuous techno-funk offset by the singer’s monotone ennui, it sounds like pre‑E New Order on a rainy Sunday (and that’s saying something). It’s the first track on Working Men’s Club, and pointedly so.

“That’s the sound of the valley in winter,” Minsky-Sargeant explains over an afternoon cup of tea in his backyard. For company we have two (I think) identical fluffy grey cats roaming the grass, his little brother’s trampoline gathering early autumn leaves and, from the steep field at the top of the garden, sheep baaing away the cloudy afternoon. “When that song came out, it expressed how I was feeling at the time. It was weird – all the music on it’s quite chirpy, maybe a bit happy, but I wanted to layer a really dark vocal and pin down how I felt.”

There is, he agrees, a psycho-geographical truth at the heart of the song. Todmorden and other towns along the Upper Calder Valley, like Hebden Bridge five miles to the northeast, grew up around the cotton mills that were motored by the River Calder and accessed by the Rochdale Canal. Hebden Bridge was famous for producing corduroy – it used to be known as “Trouser Town”. One of the historical figureheads of the long, thin market town the locals call Tod is industrialist John Fielden. Minsky-Sargeant explains how the radical Quaker MP, known locally as “Honest John” and memorialised in a statue in nearby Centre Vale Park, was instrumental in the passing of 1847’s Ten Hours Act, which limited the working hours of women and children in textile mills.

So, being in a valley brought power, prosperity and a sense of community. But, equally, by definition, it means being at the bottom of a topographical depression. Being down in the valley means being down in the shadows.

“I remember driving back with my dad from his to school on a Monday morning after I’d spent the weekend with him. And as you come away from Manchester, through Rochdale way, the sun just goes. You lose it, and are left with this kind of white light, like you see there,” he gestures behind my head, up the hill, “and he’s like: ‘Ah, we’re in Tod now.’

“Yeah, a lot of people here get that seasonal depression,” nods Minsky-Sargeant. Yes, Todmorden has The Golden Lion, the brilliant pub and venue that hosted many an Andrew Weatherall DJ set. And Hebden Bridge has The Trades Club, another great local venue. But still. Isolation and gloom and seasonal-affective-disorder.

“I was on a walk the other day with a couple of mates and we were like: ‘Yeah, it’s coming, innit? You can feel it. The sun’s going away.’ It dwells on a lot of people, that. As you grow up with it, you get used to it. But then it does start to drive you slightly insane. That’s when people go: ‘Fuck it, I’m getting out of here.’”

Minsky-Sargean got out of here by going deeper. Working Men’s Club is the thrilling, energising, bracing sound of a reformed indie kid who side-lined the guitars and amped up the post-industrial synths, glacial beats and a bored-but-impassioned vocal style pitched somewhere between Ian Curtis and Mark E. Smith.

Stand-outs? On Working Men’s Club, they’re all stand-outs. But the acerbic death-disco of Cook A Coffee deserves mention for curt lines “tune into the BBC and watch me… defecate… you look like a cunt…”, which are even better when you know they were inspired by right-wing TV commentariat windbag Andrew Neil.

“I was just angry and channelled it through that. He doesn’t believe in climate change, does he, and he’s just bolshy and bullies people. But in the broader sense, it was channelling my anger at the media,” he says of the old stuffy white guys who run it, “and how that exploits and manipulates normal people.”

They, the songwriter says, are helping foment an ever-more-divisive politics and adversarial society. Him, he’ll have a conversation with anyone. But Minsky-Sargeant is of the firm opinion that our current so-called leaders and the broader Establishment relish setting us against each other.

“Maybe I wouldn’t pick up on that if [it wasn’t for] life experience. I got racially abused at school, because my dad’s Jewish,” he says. The Minsky part of his name comes from family who fled prejudice and pogroms in Belarus, Poland and Ukraine. “So I’m slightly Jewish. I’m just as British as you, but we’d be learning about World War Two and they’d be calling me a yid. It’s just ever-more like the 40s, innit? How can it only be that short a time and we’re back to where we were? How have we not learnt from that? I just can’t fathom it, really.”

Then there’s Angel, running at 12-and-a-half minutes and closing the album. There are hints of I Am The Resurrection-esque euphoria in there. But there is, too, something darker, angrier.

“Yeah, it’s quite a personal tune, really. I wrote the lyrics before going to a funeral, someone slightly older than me… I won’t elaborate. There wasn’t much I had to say, just little bits, so then I wrote lots of guitar lines.”

But he had to write it.

“I think music is ever-less emotive. People don’t look into themselves, they just look out and talk about boring things. There’s less emotion within what is classed as the indie scene. But it’s really important to me to express how you feel through your art.”

Working Men’s Club is both claustrophobic and epic, which feels very 2020, even as the album also feels very late 70s Sheffield and Manchester in its echoes of Cabaret Voltaire and A Certain Ratio. It’s a fitting release at a time when the label behind it, Heavenly, is celebrating 30 years of magic and discovery with the likes of The Chemical Brothers, Manic Street Preachers and the aforesaid late, great Lord Weatherall.

It’s also a frustrating album because you want to, need to, dance to WMC, in a room, with other people, with sweat and recklessness and spilt drinks. To bastardise the title of their record label’s legendary 90s club nights, Heavenly Social Distancing just doesn’t compute.

Ah well. Next year. Hopefully. First round’s on me.

Credit, in part, Ross Orton, Sheffield-based producer of Arctic Monkeys (big shout for his work on helping shape the tough, hips-centred sound of AM), M.I.A. and The Fall. A former member of Add N To (X) and Fat Truckers, he’s both Minsky-Sargeant’s studio wingman and his sidekick in their band Minsky Rock (the offshoot duo promises an EP before year’s end and, for now, a 21-minute WMC electro-bass-vocoder “megamix” that is best experienced in this live iteration.)

Credit, too, bass player Liam Ogburn and guitarists/keyboardists Mairead O’Connor (The Moonlandingz) and Rob Graham (Drenge), all of whom were recruited by Minsky-Sargeant after the first line-up (Minsky-Sargeant with guitarist Giulia Bonometti and drummer Jake Bogacki) disintegrated in the wake of the release of debut single Bad Blood.

But credit, mostly, this forward-facing teenager for being smart and decisive, for realising this brand new band were headed towards a dead-end already. “I was getting to the point where normal guitar music was really boring me,” Minsky-Sargeant says of the band’s reshuffle. “What new can you do with it? Unless you do it really fucking well, but even then…” He tails off, because that’s what guitar music does too often: tails off. “For me, making music is about retaining a form of excitement up there,” he says, tapping his temple. “It’s quite a… not selfish process, but I’m doing it to excite myself, as a songwriter. I’m being creative to keep me happy.”

That switch-around, he adds, was part-catalysed by Heavenly.

“The best thing they then did was put us in [the studio] with Ross, who changed my perception of making music, really. He didn’t take over, he just showed me a new way of doing stuff in a really creative way. Just making it exciting. He did that with Teeth. It was my tune, that, so it was the first time I had ultimate control. It felt like he just channelled my idea and captured it perfectly. Then, going into a different world of making dance music – I kinda made that tune as a joke,” he admits, “but Jeff said that should be our first single. So then I was like: fuckin’ hell, I better get my shit together.”

Syd Minsky-Sargeant

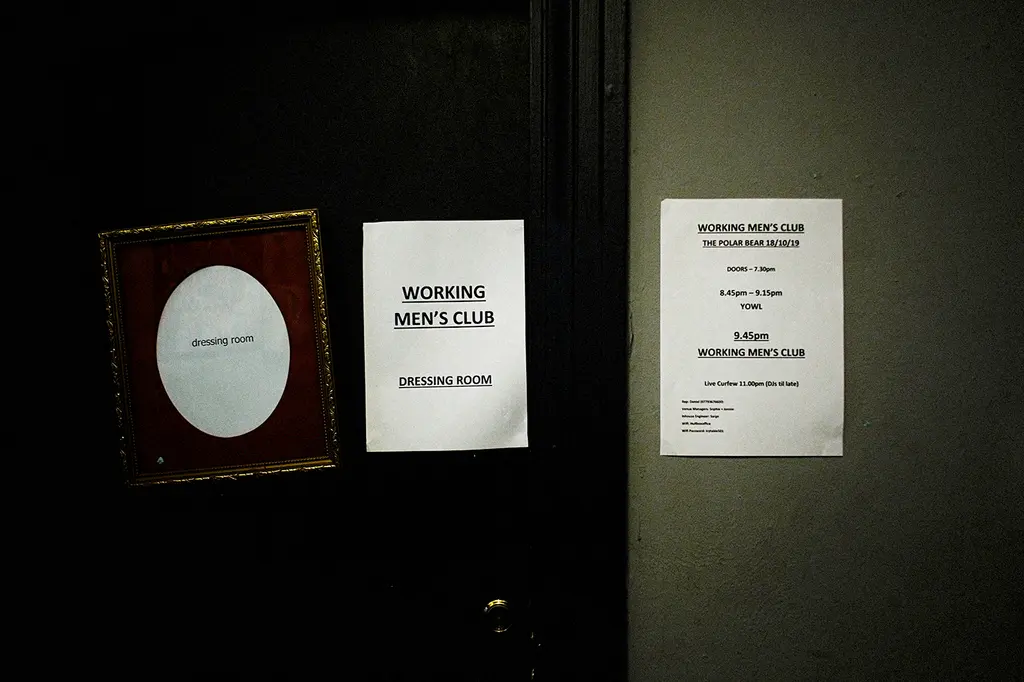

Working Men’s Club was recorded with Ross Orton in Sheffield in 10 days right before Christmas 2019. The 10 freshly-composed songs were the sounds of Minsky-Sargeant processing both his background – that hearse-shaped valley – and the internal tensions with the original line-up as WMC mark #1 undertook a “massive” tour in October and November that year.

“I was just writing in between [gigs] – I had a lot to let out,” he says of a period which climaxed with both Bonometti and Bogacki leaving the band before the recording of the album. “The songs just spewed out.”

As well as using the Korg synthesiser and Roland drum machine, he also wrote more using the bass as his primary instrument. “That means the songs are more about groove,” he says, simply.

A funk influence, meanwhile, bubbled up from Afrobeat, which comprises a significant part of his stepdad’s record collection. Minsky-Sargeant shows me a 2009 compilation on his phone, Nigeria 70 – Funky Lagos, which you know is going to be great by the cover alone. That was his route into the Fantastic Man himself William Onyeabor, “bits of” Joni Haastrup (Nigeria’s “Soul Brother Number One”) and, then, Ghanaian disco-era keyboard wizard Kiki Guyan.

Also feeding in were the acts he saw at The Golden Lion: Argentinian psych bands “and weird shit like that”, Luke Unabomber and Justin Robertson. The latter was the best DJ he’s ever seen although, to his regret, he never saw Weatherall. “He was a proper punk. There’s not enough of that left. You shouldn’t conform, really. That’s the thing that really annoys me about guitar music: it’s really conformative [sic] now. People just wait till something’s trendy then latch onto that.”

His band’s name also reflects the importance of his local, and of his locale.

“I think it just summarises northern culture. I’m not a working-class kid so I don’t want to appropriate [anything more]. It just symbolises normality to me, and cooperation within all forms of society. I’d say my working men’s club is The Golden Lion. Takes in anyone and everything, whatever it is. They’ll put on a pub band, and they’ll put on Weatherall. They won’t segregate.”

That attitude – open-minded, embracing, idiosyncratic – is, he thinks, what sets WMC apart.

“I don’t have a problem with any particular band. I just think do your own thing. I’ve been aggy before about people and obviously, stuff gets on my tits. But it’s more interesting when we talk about the general problem rather than just putting it on other people. It’s not their fault – it’s a problem higher up. The only reason certain bands get played is because some people are making decisions [like] ‘we should play them’. But that’s the same for us,” he acknowledges. “It’s just that everything feels so institutionalised. That’s what annoys me.”

And here, in fact, the isolation of Tod is a boon. They’re not in Manchester, or Sheffield, or Leeds. They’re in the valley.

“We’re not being told what to do by society, we’re just making it up. There’s no bubble of what’s trendy and what’s cool. You’re not seeing what the fashion is. You’re not down in London. You just get on with it. And you never think someone’s gonna listen to your music.”

“I feel sorry for [bands] in London, actually. It feels like wherever they go, there’s always gonna be someone connected, so you’re written off at the first minute. But we’re not perfectly formed,” Minsky-Sargeant states firmly. “That’s something I want to make clear. This isn’t a defining album for me. This defines two years of my life. It doesn’t define me as a songwriter. Which is why it was important to change so quickly. And to keep changing.”

We finish our tea and head up into the sheep field and onto hilltop farmland. Syd Minsky-Sargeant walked these high paths during lockdown, thinking, writing, escaping.

He points out on the opposite side of the valley Stoodley Pike Monument, a 19th century tower commemorating the Battle of Waterloo and the Crimean War, and Widdop and Gorpley Reservoirs. They attract the tourists, but no one really comes up this side. It’s his space, up high, free.

After walking a while across fields and dry stone dykes, we drop back down into the valley and into Todmorden. Destination, The Golden Lion, his working men’s club. We work our way through the draught lager selection, and have a Thai curry. It’s a great boozer, even with masked bar staff, table-service-only and early-doors closing. You can see why he likes it.

Earlier he’d told me about some pivotal advice he’d received, aged 14, from Alex Wonk of cult Croydon outfit Wonk Unit, a “proper indie/DIY punk band. Proper good guy.” Wonk impressed upon young Syd something obvious, but no less important, something fellow Yorkshireman Alex Turner also got instinctively: write about what you feel, what you know.

“I’d always done that subconsciously. But I thought, yeah, that is the code about how you should write. Throughout that entire record, that’s what I tried to do on each song.”

Two nights later, I see him in a pub in my neighbourhood, at east London’s Dalston Roof Park, a different kind of hill and vantage point. Working Men’s Club are launching Working Men’s Club with a party, DJ set and screening of a film shot at an audience-free gig in an underground warehouse space in Manchester. Which is as close as we’ll get to a gig right now.

The mood is up. Last night, the band held a launch party in The Golden Lion. Minsky-Sargeant was chuffed that his family could be there, celebrating with him. Tomorrow, another, similar do at Bodega in Nottingham, then, the following night, The Brudenell in Leeds. Then, three socially distanced shows in one day at YES in Manchester. Then, major, just secured, a slot on the BBC’s Later… With Jools Holland, still the pre-eminent (actually, only) music show on British terrestrial telly. For Working Men’s Club, working for a living and putting on a show, even – especially – in these blighted times, is what matters.

When I leave, Syd Minsky-Sargeant is manning the decks, spinning tunes with his bandmate Ogburn. They’ll have to drag him off, come kicking-out time. That’s only 10pm, but that’s OK.

Working Men’s Club is out now via Heavenly