Capturing Black British life beyond the M25

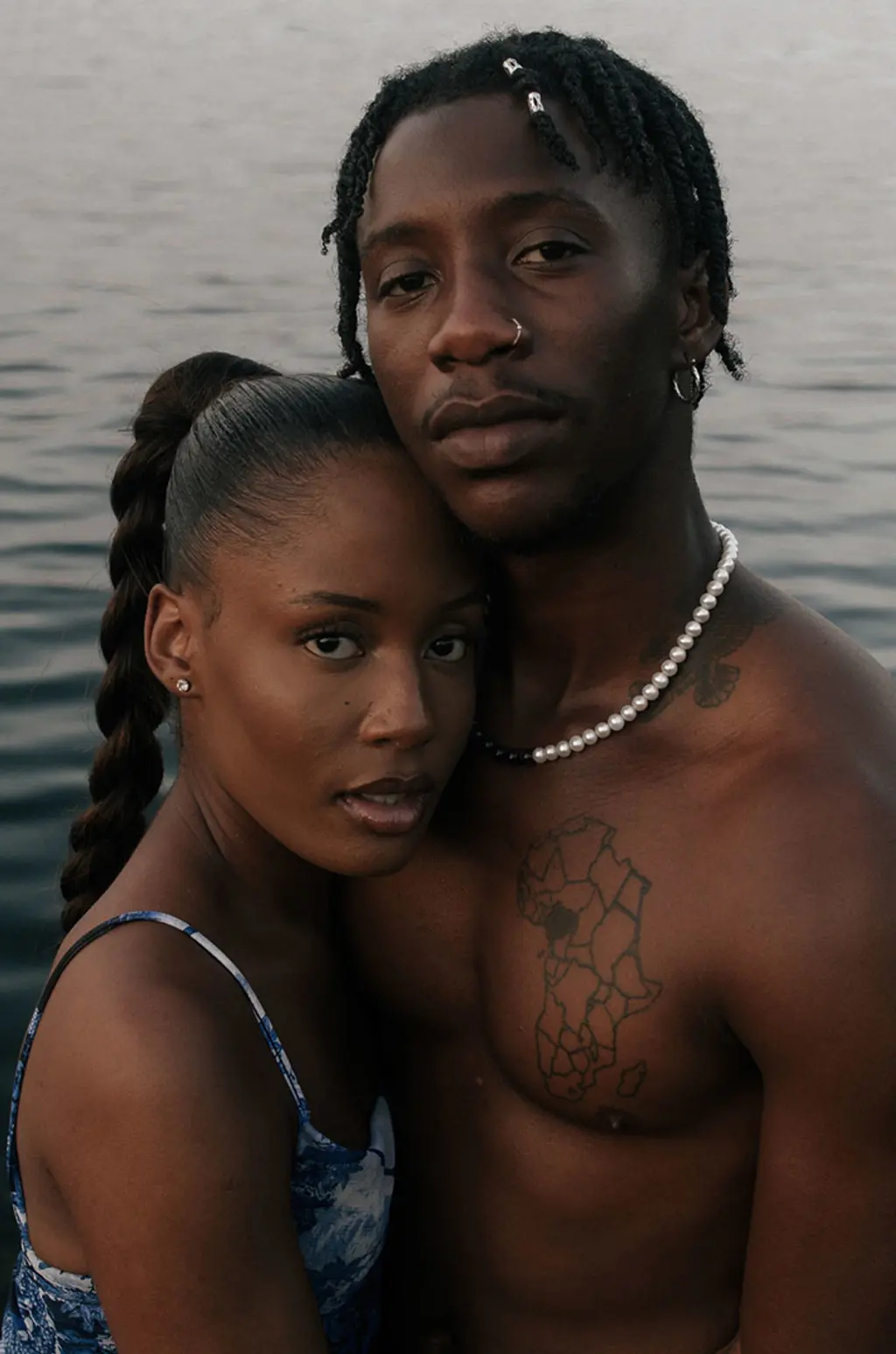

Photographer Karis Beaumont's Bumpkin Files wants to dispel myths that Black people living outside of London are not “in touch with their Blackness”.

Society

Words: Lola Christina Alao

Photography: Karis Beaumont

If you are Black and living in a rural area, chances are you will have been made aware of your race at school, in supermarkets, at work and even while you’re walking down the street. It doesn’t help that the media perception of Black people, and other minorities, show them only living in London. However, 2011 statistics show that 42 per cent of Black people do live outside of London.

This is the focus of Bumpkin Files, a platform, community resource and archival project by photographer Karis Beaumont. The 25-year-old created the project in 2017 to document and amplify the experiences of Black people in Britain who don’t live in London and to dispel the myth that Black people living outside of London are not “in touch with their Blackness” or do not align with “Black culture.”

Originally from Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, where she is currently based, Beaumont’s own background fuelled her to tell her own story and the stories of others who grew up in Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire. Bumpkin Files pays homage to the Black people that came before us including the Windrush generation and Black figureheads who fought for racial equality in the ’60s and beyond, as well as the underrepresented and often undocumented stories of Black people today.

Her recent work, a collaboration between Bumpkin Files and BLK Brit — a UK-based digital platform that explores modern Black British life — sees creatives Jahmel Coleman and Mel McKoy sharing their unique and often-overlooked Black British experiences while exploring common misconceptions associated with Black Britons beyond London.

Below, we catch up with Beaumont about her photography journey and how her Jamaican heritage and Hertfordshire upbringing influences her creative expression.

Can you tell me a bit about where Bumpkin Files’ journey began and how you came up with the concept?

In 2016, I had a conversation with my dad, who’s from Hertfordshire as well. He was telling me stories about his upbringing and I really engaged with them at a different level. In 2017, I saw a few Black British platforms pop up, which I loved, but I kept seeing mainly just London stories.

That got me wanting to start up conversations. It started off as a really, really small 9archive project where I scanned family photo albums and put it on my website. From there, I decided to start up a portrait series, documenting present day Black Britain. During my research, it was hard trying to find pictures of Black people across the country. There isn’t a whole lot and it isn’t that accessible. I think this is due to lack of documenting stories on a mainstream level and a lack of resources, too. Some county councils make it difficult for some communities to throw events or utilise space/facilities. So it’s important for me to document us in areas that aren’t being covered.

How did you come up with the name for Bumpkin Files?

Originally, I called the project Country Bumpkins. But then I was like, there are already a lot of companies or cafes called that. And it just came to me, I wanted to keep Bumpkin in there. Then I just added Files because it made sense for the direction I wanted to go. And it just stuck with me.

What are the common misconceptions about Black people living in the countryside and how does Bumpkin Files aim to dispel these myths?

A common misconception is that we have little to no connection or contribution to Black culture/history, and that we don’t have thriving communities. Bumpkin Files’ aim is to provide more representation and reference to these often overlooked communities through visual storytelling and community engagement.

What was life like growing up in Hertfordshire?

Growing up, I knew I was different from school peers, especially in primary school – but it wasn’t something that used to get me down. I grew up in a Hertfordshire town, and felt different from my school peers as I was shy and liked to play football with the boys. I used to be a big tomboy, so being Black on top of that made me stick out more. I was okay with that though, just more aware of myself.

There was always a lot of culture in my household. We’d spend a lot of time at my grandmother’s house (my mother’s mum), who lived in another part of Hertfordshire where there’s a very present Black community, so I was always surrounded by Jamaican culture. I guess I’m blessed in that way, because it’s not like that for everybody.

Did your family move from the countryside in Jamaica and did they feel “at home” in the British countryside when they came here?

I’m unsure of the reasons why they chose to move to Hertfordshire, but my paternal grandparents are both from the country back home, and moved to Brixton first before they settled in the countryside. My maternal grandfather was also from the country back home. My mum and siblings lived in a house with a big garden so my grandparents, grandfather especially, used the garden to raise livestock and grow vegetables like callaloo and pumpkin.

Would you say your Jamaican heritage influences your work?

Jamaicans are very expressive, from style to music. And I’ve always expressed myself creatively, even before photography. So in photography, I take my time and ensure there’s some sort of stylistic flair to it, but I like capturing emotion as well. And I try to captivate confidence so even if people are feeling shy, I like to gas them up. Even on Bumpkin Files’ side, it was about paying homage to people who came before us. People from the Windrush era and the boycotts they had to do to get certain racial laws put in place, like the Bristol bus boycotts which resulted in the Race Relations Act being passed in 1965, which made racial discrimination unlawful in public places – followed by the Race Relations Act 1968 which extended the provisions to housing and employment. If it wasn’t for them, we wouldn’t even be able to venture and experiment in such a freeing and creative space. I always have my elders in mind when I’m creating.

When did you get into photography?

I started in 2015 in the middle of my studies (Tourism Management at Hertfordshire University). And around that time, I was already saving up for a camera, but mainly for styling and fashion purposes. I stumbled across it. I already had a couple of connections with people in the creative industry, Ibrahim from GUAP magazine was one of them. And then I just ended up being their photographer for a couple of years and fell in love with it. As I’ve gotten older, I realised that I’ve always had a love for photography. I just didn’t see myself in that space because it was mainly white middle aged men with like, super expensive cameras.

What is the relationship between you and your subjects? How do you get that sense of authenticity to come through in your work?

A lot of people I’ve been shooting with are friends, friends of friends or acquaintances. So far, my subjects have been from Hertfordshire and Buckinghamshire, but moving forward I’ll be documenting other parts of the countryside in the UK and Europe, and documenting other cities and towns. My job as a photographer is making people feel safe and comfortable. So it’s always good to have a chit chat with them and, you know, build a rapport to ensure that they’re okay as well. The more respect you approach subjects with, the better the job will be and the better the vibe.

What are the main themes that you like to explore in your work?

Beauty, definitely. Joy, definitely. And authenticity. I also always try to incorporate emotion and humanity into everything. Especially when I’m working with music artists or high profile people. People often forget that they’re also human who have likes and dislikes and get nervous.

And why is Black Joy particularly important to you?

A lot of the time we get a programme or film with a Black cast, it goes back to trauma, or us being degraded. And as much as we have gone through a lot of trauma, we live it, so we don’t have to keep seeing it on our screens. That’s just gonna continue mashing up our psyche. We’re so complex and multi-layered so it’s super important to document Black joy.

Where would you like to take Bumpkin Files in the future?

I want to continue working with existing platforms, and growing out the archive, collecting images, and telling stories. On a bigger scale, I want to take Bumpkin Files to mainland Europe. In France, the majority of the Black population are in Paris, but I’m sure there’s similar experiences in the sense of what’s been documented. And even going into places like Poland or like Finland, because you don’t often hear about Black Finnish people for example. I also want to go to the US and meet Black people from the country. When all areas of the diaspora are covered, it benefits everybody. And it saves the next generations having similar conversations that we’re having.

When someone looks at Bumpkin Files as a body of work, how do you want them to feel? And what do you want them to take from it?

I want them to feel curious and encouraged to dig deeper. And even for other visual artists, journalists, or students to look at Bumpkin Files and think, ‘I know of some communities I could document myself’. I just want to highlight the importance of documenting, no matter where you’re from. If you’re from the city, if you’re from the capital, keep documenting your stories because we need them. We don’t want it to be erased, destroyed and burnt down like it has been.