Meet the “lunatics” fighting for psychiatry abolition at Mad Pride

This year, the celebration returned to Britain for the first time in a decade. Here’s why this group is pushing against detainment and reclaiming the idea of “madness”.

Society

Words & photography: Molly Lipson

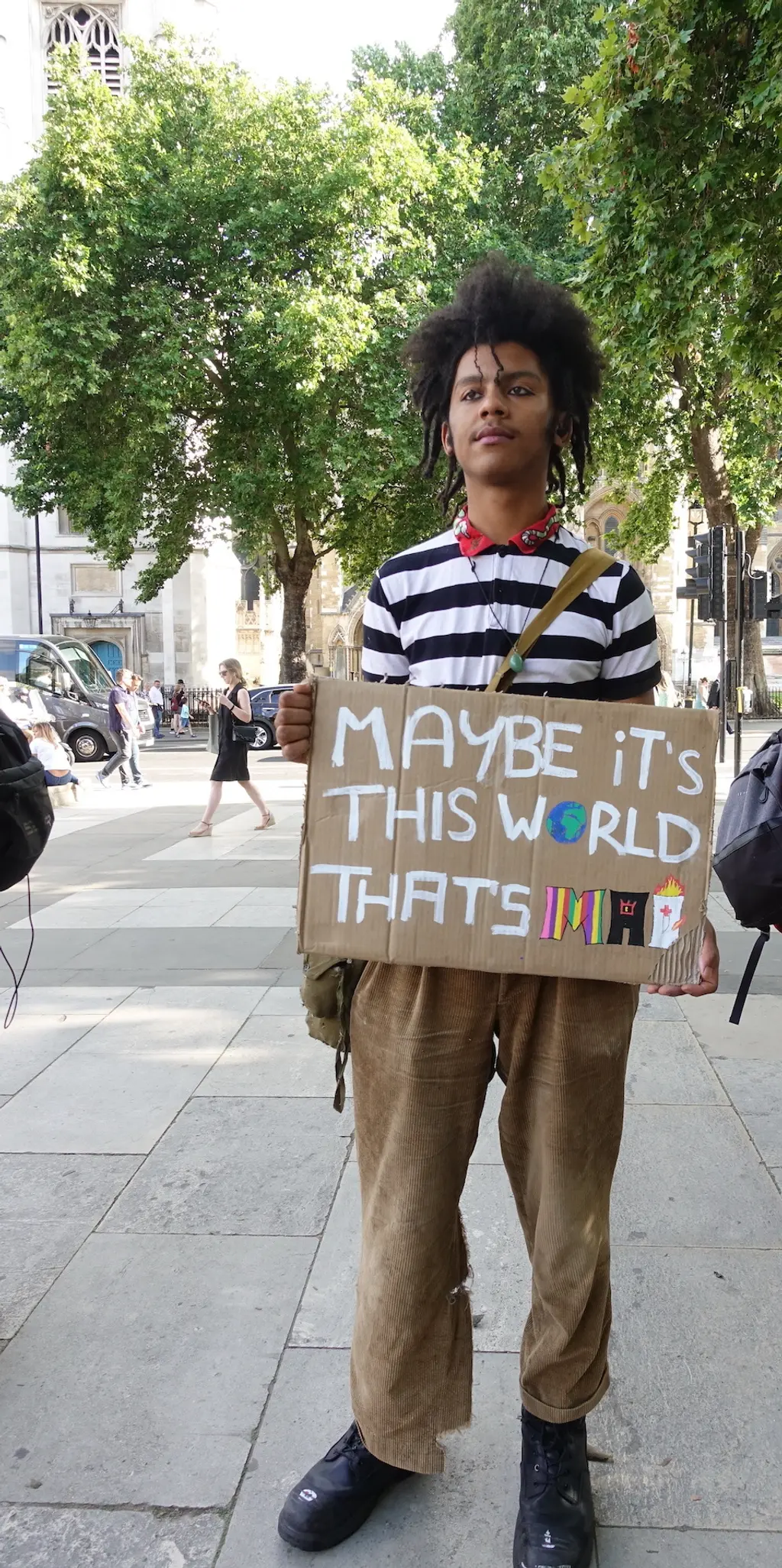

A small group of people assembled around the far side of Parliament Square last week, on July 14th. As more and more joined, soon there were around 70 attendees armed with placards reading “fire to the psych wards”, “the patients lost their patience” and “disordered and ready to organise.” Mad Pride 2022 was well underway.

There was a festival feel in the air, akin to what you’d expect from the previous month’s LGBTQ+ parade (which is where the event stems from). It was a warm summer’s evening and many people had turned up wearing hospital gowns painted with anarchist signs and anti-psychiatry slogans. There was a large table laid out with food and, across the crowd, people were waving to friends from other organising groups they hadn’t seen in a while.

Mad Pride first began in Canada in 1993, then known as Psychiatric Survivors’ Pride Day. The movement soon spread to the UK, and in 1999 there were a series of concerts, festivals and protests that took place regularly until the early 2010s. After the deaths of a number of key organisers, there hadn’t been a celebration of Mad Pride for over a decade – until now.

Its comeback reflects urgent issues within the psychiatric system, where more people die than in any other form of detainment in the UK, yet there is no legal precedent to investigate these deaths. Many psych survivors – people who have been sectioned under the Mental Health Act, kept in inpatient units or gone through the psychiatric system – also consider this number to include deaths caused due to the lack of care both inside and outside psych wards.

During the event, someone from the group who’d organised the Campaign for Psych Abolition (CPA), addressed the crowd on the mic. Medusa (an alias she uses in place of her real name) spoke about her own experience of madness and what abolishing the psych system means to her. Halfway through her speech, she broke down in tears as she recalled the many names of those who have been killed by the system.

The CPA was set up in August 2021 and is led by psychiatric survivors. As an abolitionist group, they fight all forms of policing, incarceration and state violence – which includes, they say, the psychiatric system.

Some of the reasons for this are clear: psychosis and other madness are treated as crimes. It is the police who have the power to section someone, and are often violent when doing so. People are then involuntarily locked up in wards where escaping or absconding (not returning to the ward after permitted leave) can be met with a criminal offence and harsh sentencing. Even assisting someone to leave a psychiatric unit is punishable by up to two years in prison.

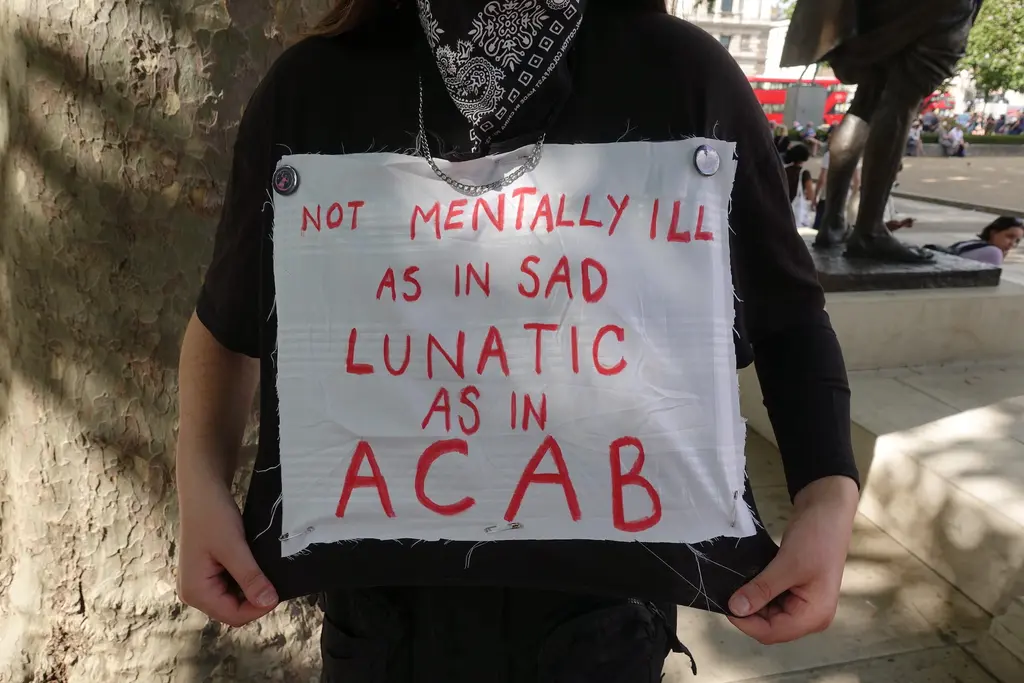

Other reasons require more explanation. The word “mad” was once considered derogatory, but psychiatric survivors have since reclaimed it, along with the labels “lunatic”, “crazy” and – Medusa’s favourite – “fucking nuts”. But it goes deeper than just semantics. Being mad has long been seen as something bad or wrong, an ailment that needs fixing. In contrast, the CPA believes that the problem lies with our society’s failure to support psychotic people properly.

“Madness is not something that should be erased in any way, shape or form,” says Medusa. “Society has made it hard – it’s not prepared to have psychotic people [in it]. It’s not us who need to change; the world needs to change.” Saoirse, another CPA organiser, agrees. “We are outside the confines [of society]. We’re agitators and delinquents on the sidelines, not ‘mentally ill’,” they tell THE FACE.

“Madness is not something that should be erased in any way, shape or form. Society has made it hard – it’s not prepared to have psychotic people [in it]”

MEDUSA

Determined to prove their agitation abilities, the CPA decided to relaunch the historic Mad Pride tradition. Following Medusa’s emotional opener, other speeches were delivered by intersecting abolition groups and other psych survivors, including talks from SOAS Detainee Support, Cradle Community, Copwatch Network, Black Mind UK and No More Exclusions. The beauty of this event was its variety: a crowd made up of “mad” people and psych survivors, but also, as Saoirse mentioned in their closing speech, those who understand the importance of psych abolition in this interconnected fight against state violence.

The event ended with a “bed push”, a tradition within the mad liberation movement where someone is pushed in a hospital bed to symbolise their return to the community following psychiatric incarceration. The bed was wheeled along the pavement at Parliament Square, making its way to Waterloo Bridge where they took to the middle of the road in protest. The mad liberation movement has gone through various iterations over the years, most prolifically emerging in the 1970s in the form of a union, the Mental Patients’ Union (MPU). Like labour organisers, mad people argued that psychiatry constituted part of the class war against working people, oppressing them through power and fear. Later versions of similar organising include the Campaign Against Psychiatric Oppression.

Although psychiatric hospitals and wards no longer treat their patients like zoo animals, as they once did in places like Bedlam, Medusa and Saoirse say they do inflict multifaceted harm on people already in vulnerable states. The first time Medusa was sectioned, she was living on the streets and was told by the on-duty psychiatrist that the unit she’d be in would have food, a bed, and that she’d be out within two weeks. She ended up being incarcerated there for a year, and was so frequently locked up in a bed-less isolation room that she rarely slept on the promised mattress. “It was horrible,” she recalls. “Not only is it not making anyone better, it’s making people significantly worse. You go [there] thinking, okay, I’ve reached rock bottom, here’s the help. Then it turns out there is no help.”

Sceptics of psych abolition are quick to ask: what about the people who are at risk to themselves or others? Although it’s a valid concern, abolitionists stress the fact that people are already dying under psychiatry. “We don’t want to recreate the psychiatric system that is, like, unless you’re dying, we don’t care,” explains Medusa. “We need to be looking after each other all the time. However, our main priority is abolishing psychiatry first because my friends are dying inside. Every second that goes by counts.”

“One of the things that we always say is that we already are doing [the alternatives] because we can’t rely on psychiatry,” adds Saoirse. The fact that waiting lists for any kind of mental health support are so long and demand crisis in order to receive treatment means that people are already having to look out for each other during those interim periods. “We’re dying while we try to keep each other alive,” Saoirse says.

Importantly, those fighting for psych abolition are not against mental healthcare. In fact, they’re all for it. “We’re begging for healthcare in the first place because psychiatry is not it,” says Medusa. As one survivor, Elle Blooms, shared on Instagram with a poem: “Crisis care is being drugged to sleep in a room carved in warnings. Crisis care is crying in the arms of another patient. Crisis care is the police in [and] out of the ward leaving bruised limbs.”

The CPA’s work has only just begun, but Mad Pride proves just how much support there is for abolishing the current system. The fight continues, and it is a fight full of love and care, of mutual aid and community resilience. As CPA says, “fuck assimilation, mad liberation!”

Follow CPA’s work on Instagram and Twitter: @cpabolition.