Songs of protest

In 2025, the face of British protest is not restricted to teenagers or students. At a time when life is hard enough for young people, the middle-aged, elderly and retired are willing to join the fight for Palestine, for the climate, for anti-racism and against far-right demonstrators. These are the power pensioners fighting peacefully, for freedom and our future.

Society

Words: Tiffany Lai

Photography: Rene Matić

Taken from the winter 25 issue of THE FACE. Get your copy here.

27TH FEBRUARY 2024: Sophie Miller, a 53-year-old artist and environmental activist, is arrested on her way to the Insure Our Future protest in London. She hasn’t even begun her planned performance as one of The Dirty Scrubbers, a satirical piece where she and fellow activists would play cleaners greenwashing corporate climate crimes. Wearing rollers, aprons and rubber gloves, they use vacuum cleaners and washing machines to “wash” money stained with fake blood and oil. But as they approach the City of London, they’re surrounded by police. “They [said] we had intent to cause criminal damage, even though we had liaised with them beforehand,” says Sophie. “It was incredibly frustrating and upsetting to be arrested for entirely peaceful and non-violent direct action.” That arrest happened when the Conservatives were still in power. Nonetheless, Sophie is firm in her view that we have a “democratic right to protest under freedom of speech [laws], and it is being absolutely eroded by this government.”

9TH AUGUST 2025: 59-year-old architect Steve Fox arrives in London’s Parliament Square at 1pm. Dressed in a white button-down shirt and wraparound tinted glasses, he’s holding a placard that reads “I oppose genocide, I support Palestine Action”. After taking a seat on the steps, he’s arrested 20 minutes later and taken to Brixton police station. Among the occupants of the police van, he is the only one who hasn’t been arrested before. Steve says his decision to risk arrest came after he became disillusioned with the effectiveness of the mass marches in support of Palestine. “They were enormous shows of solidarity but they had become neutered,” he says. Accordingly, when he saw Defend Our Juries’ tactic of having protestors test the banning of Palestine Action by holding up placards declaring their support for the organisation, he “thought that was a brilliant idea”.

6TH SEPTEMBER 2025: It’s an unusually warm September’s day in central London as scattered applause rises from Parliament Square. “You’re a hero, Sue!” someone shouts. Gingerly stepping down from the lawn onto the pavement is Reverend Sue Parfitt, an 83-year-old Anglican priest. Dressed in a clerical collar, a pair of Palestine flag earrings and an oversized crucifix necklace, Sue has been sitting in her camping chair and holding a placard for more than six hours. Now she’s being arrested under section 13 of the Terrorism Act 2000. As she slowly treads along the pavement, one of the four arresting officers holds onto the back of her right elbow as she leans into her walking stick. Speaking to ITV News earlier in the day, she said: “The truth is that Palestine Action is not a terrorist organisation. It caused much damage confined to the weapons [at RAF Brize Norton, costing £7 million to repair] that are being used on the Palestinians. All of us with any moral backbone at all must stand up against this.” It isn’t the first time Sue has been arrested and it won’t be her last.

6TH SEPTEMBER 2025: A few hours after Sue’s arrest, blind and disabled 62-year-old activist Mike Higgins is being wheeled backwards in a wheelchair towards a police van parked outside the House of Com- mons. Wearing a black suit, he holds his placard in support of Palestine Action in his left hand and, in his right, a white cane. It’s already dark by this time but he’s lit by the phones of a large, supportive crowd. Shouts ring out of “Shame on you!” at the arresting officers taking Mike away. Speaking to PA news agency that afternoon, he said: “What choice do I have? Nothing is being done about the genocide other than by us. And I’m a terrorist? That’s the joke of it.”

That early September day in London, 857 people in total were arrested under Section 13, which is the Home Office legislation classifying Palestine Action as a terrorist organisation. The previous month, on the day that Steve was carted off to Brixton, 522 people were arrested for displaying placards. Half were aged 60-plus, including more than 100 in their seventies and above.

For many older protesters, even those who are seasoned campaigners, the decision to fall foul of the law doesn’t come easily. But for those who risk it, they see it as a responsibility. Paul O’Brien is a 74-year-old doctor who has been arrested at two protests this year for holding a placard. He’s the founder of pensionersforpalestine.com, a site that highlights the reduced risk for older people, relatively speaking and compared with younger generations, when it comes to non-violent direct action. On the homepage is a banner that reads “Now Is Our Time” – and, in a playful nod to the site’s target demographic: “Are you old? Do your joints creak a bit? Hard to hear your children? What did I do yesterday?”

“The consequences for us are much less,” says Paul. “If they fire me, what difference does it make? I’ll be retiring anyway. But for younger people, some of these things have long-term implications.”

All of which points to a unique moment of democratic mobilisation. There have, of course, always been activists who are grey of hair and strong of will. But this feels different, not only in its scale but in its cross-generational solidarity.

Here, we speak to those with the posters and the placards, one, two or even three generations older than the average FACE reader, who have been risking their liberty in pursuit of causes they – we – hold dear.

Luke Daniels, 75, Guyana

Author, former carer co-ordinator and health services trainer; counsellor for perpetrators of domestic violence; president of Caribbean Labour Solidarity

PROTEST HISTORY:

- Black People’s Day of Action, March 1981

- Falklands War, 1982

- Protest against the killing of Dorothy “Cherry” Grose, 1985

- Picketed the South African Embassy (London) against apartheid, 1986 – 1990

- Iraq war, 2003

- Picket of South Africa House for the killing of the Marikana miners, 2015

- March against violence against women and girls in Johannesburg, 2019

- Picketed the Kenyan Embassy for sending police to Haiti, 2023

- Picketed the Canadian Embassy for involvement in Haitian conflict, 2023

- Stand Up to Racism, 2025

- Anti-fascist demo at Epping Bell Hotel, 2025 * Opposed far-right protest at Thistle Hotel, Barbican, 2025

- Donald Trump UK visit, 2025

- Palestine protests, 2025

- Birmingham bin workers’ demonstration, 2025

What was your political awakening?

Studying Caribbean history at school. When I read about the trans-Atlantic slave trade I was so mad about people being so badly mistreated. I was around 15.

It feels like the right to protest is on precarious ground at the moment. Has it felt like this before?

In the 40 years or so that I’ve been in this country the political situation seems worse than it’s ever been. We’ve always had the issue of [migrant] numbers and the focus on immigrants has always been a feature of most of the elections in this country. But during this period, it seems to be on steroids. We’ve got three main political parties seemingly trying to outdo each other on who can be the most horrible to immigrants. Black people have supported Labour throughout history, so for the leader to be borrowing language from Enoch Powell is ridiculous. [On 12 May, Starmer said the UK risked becoming an “island of strangers”, evoking Powell’s 1968 notorious “rivers of blood” speech. After a furious backlash, the PM said he “deeply regretted” using the term.]

You’re president of Caribbean Labour Solidarity. Has it been hard to get young people involved?

There’s not enough of them, and this is the real challenge for us, especially now that we see fascism is on the increase. We need young Black people to be more prepared to get on the streets and demonstrate and stand up to racism.

Is there any type of messaging you think people should be wary of?

Most of the time, when they bring in draconian changes, it’s to combat immigrants. They use race. They say: “We’re under attack, we’re just targeting [certain] people.” But eventually it will affect [all] working people in the UK. The rise of Farage might seem attractive to some people. But in the end, they will pay the price, because when you stop immigrants from coming, the health service will be almost at the point of collapse, as will teaching and public transport. Anti-immigration has become the dog whistle for racism and that’s what people need to wake up to.

You’ve been an activist for many years. What continues to drive you?

Hope. We’re reminded by [African academic] Professor Hakim Adi that one of the biggest movements this country ever had was the anti-slavery movement. The people have a sense of justice and what’s right. It’s deeply embedded within society.

Paul O’Brien, 74, Cork

NHS doctor

PROTEST HISTORY:

- Contraception Action Programme in Ireland, 1976

- Irish hunger strikes campaign, 1981

- Carnsore Point anti-nuclear campaign, 1978 – 1981

- Troops Out Movement, mid-1980s

- Occupy, 2012

- Swim with Gaza, 2023

- Camden Friends of Palestine, 2023 onwards

What were the first campaigns you were involved in?

I was involved in the Contraception Action Programme in Cork, because back then, in the ’70s, you couldn’t even get a condom. We campaigned there for the availability of contraception for women in Ireland. Then, in the early ’80s, I got involved in the campaign around the hunger strikes [by imprisoned IRA men]. I was working on an oil rig off the coast of Clair and when one of the hunger strikers died, I helped organise a strike that shut down the rig for an hour. We did this on two occasions and the boss of the rig threatened to throw me overboard!

You’ve stood in solidarity with Palestine for most of your adult life. Where does that come from?

Irish people seem to find it easy to empathise with what’s happening in Palestine. We feel the similarity between the kind of colonisation that happened there and what happened in Ireland [at the hands of the British].

In what way?

When we learnt about the Northern Ireland civil rights movement in the ’70s, we learned more about the role of British imperialism. In 1916, we had the Easter Rising [against British rule]. In 1917, Britain signed the Balfour Declaration [sup- porting the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people”] that was unbelievably cruel for the indigenous people. The same happened in Ireland. Our consciousness of the experience of famine is deep in our culture. In Gaza, 6,000 people need prosthetic limbs. Many of them are children. Now, I’m trying to get involved in procuring and delivering limbs for them.

You’ve been arrested multiple times. Do you fear going to jail?

I think it’s unlikely that we’ll be sent to prison. They don’t want a whole load of old people in there, it’s not a good look. Plus, they’ll have to increase the number of prison staff for all the transport to hospital appointments.

What keeps you hopeful?

Committed young people who also like a laugh – that’s what will keep them buoyant through difficult times. I’ll be gone in 20 years’ time or less, but I’m going to be watching from above. I’ll be shouting at all these young people and clapping when they do something great. If they listen carefully enough, they’ll hear my claps from the sky. The future depends on them. It’s a beautiful world with beautiful people.

1] 1981 New Cross Fire March, Crowds of Protesters, Black Britain (2021), Kinolibrary. 16 Apr.

[Accessed 5 Nov, 2025]

[2] Tom Dunne — What happened at Carnsore (2016), RTÉ One.

[Accessed 5 Nov, 2025]

[2] Tom Dunne — What happened at Carnsore (2016), RTÉ One.

[Accessed 5 Nov, 2025]

[3] Iraq War 20th Anniversary: “Don’t attack Iraq!” – Historic Stop the War March (2023). ITN Archive. [Accessed 5 Nov, 2025

[4] The Troubles ’89 | Rare Foot- age of 20th Anniversary of British Troops in Northern Ireland (2025), ITN Archive.

[Accessed 5 Nov, 2025]

Sophie Miller, 53, Cornwall

Artist, rewilder and activist

PROTEST HISTORY:

- Grants Not Loans, 1989

- Poll tax, 1990

- Iraq war, 2003

- Refugee crisis: direct aid coordinating and sending ambulances and medical aid to Syria via Turkey, 2015 – 16

- Sent direct aid to Calais refugee camp, 2015 – 16

- Extinction Rebellion, 2018 – 2024

- Ocean Rebellion, 2020 – 2024

- COP26, Glasgow, 2021

- G7, 2022

- Rainforest restoration and species re-introduction, 2023 – 2025

- Defend Our Juries 2024 – 2025

What was the first protest you attended?

It was when I was in sixth form. The Conservative government had just announced plans to replace the old grant system – where university fees and living allowances were covered by the state – with student loans. Suddenly, young people were facing the prospect of graduating with massive debts. It struck me as deeply unfair and unequal. I wasn’t particularly politically active at the time, but when I came across the protest in the street, I joined in. It was the first time I realised that collective action could be a way to stand up for fairness.

It feels like the right to protest is on precarious ground. Has it felt like this before?

The right to protest has always been essential in a democracy, but it’s now being steadily undermined. The previous government began that process – particularly under [then-Home Secretary] Priti Patel – and this one seems intent on continuing it. To me, that shows exactly why it’s so important that we keep using those freedoms. The more fragile they become, the more vital it is to protect them through action and solidarity.

There’s a sense that things are particularly bad right now. For young people, it feels like a singular moment. What would you say to that?

It does feel bleak. The rise of the far right is genuinely terrifying, climate breakdown is an existential threat and proscribing non-violent activist groups like Palestine Action undermines freedom of speech. It’s overwhelming. But silence, numbness or complacency would be even more dangerous. Maybe every generation feels like they’re living through the worst of times, but I think what matters is how we respond. I’d say to young people: look after yourselves and each other. Caring for ourselves, our communities and the planet is itself a radical act of resistance. There’s hope in that – in kindness, creativity and solidarity.

[5] Occupy London protest: on the steps of St Paul’s cathedral (2011), The Guardian. [Accessed 5 Nov, 2025]

[6] BBC News Report — Poll Tax Pro- tests (2017), VHS Video Vault. [Accessed 5 Nov, 2025]

[7] 1990: Chaos, Carnage & Bloodshed in Poll Tax Riots (2022), ITN Archive. [Accessed 5 Nov, 2025]

[8] Anti-Apartheid Movement March and Rally at Hyde Park 1988 (2014), Forward to Freedom.

[Accessed 5 Nov, 2025]

[9] ITV Evening News | Stonehenge | 19 June 2024 | Just Stop Oil (2024), via Just Stop Oil.

[Accessed 5 Nov, 2025]

Paul Renny, 67 and Shezan Renny, 55, both London

Retired trade unionist and special needs assistant, and teacher

PROTEST HISTORY:

PAUL:

- Solidarity movement with Chile, 1973

- Active trade unionist, 1977 onwards

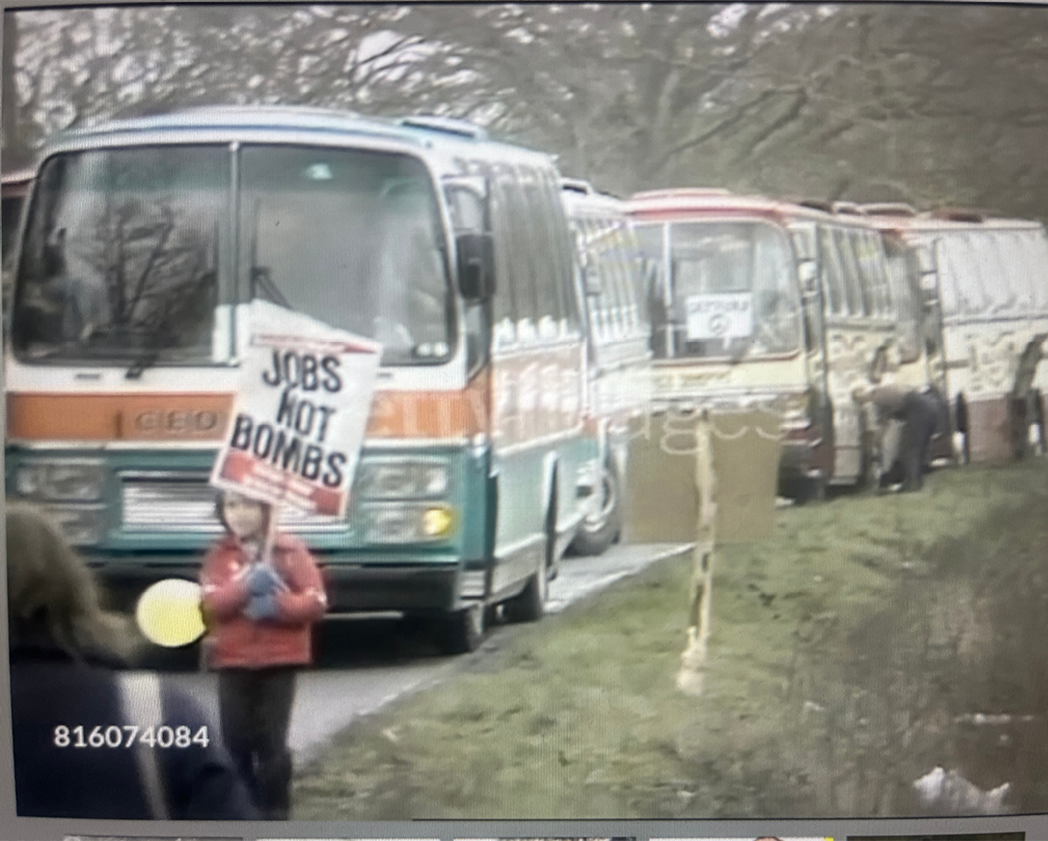

- Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, 1980s

- Anti-apartheid demonstrations, 1980s

- Miners Support Group, 1984 – 85

- Poll tax, 1990

- Palestine Solidarity Campaign, 1980s onwards

- Iraq war, 2003

- Co-founded Camden United Against Racism, 2024

SHEZAN:

- Palestine demos, 2012 onwards

- Deaths in custody campaigning, 2018

- Streets Kitchen homeless service, 2019 onwards

- Windrush, 2019 onwards

- COP25, 2019

- Black Lives Matter, 2020

- Windrush, 2021

- Co-founded Camden United Against Racism, 2024

Last year you co-founded Camden United Against Racism. Why?

PAUL: We set it up in response to the Southport riots [in 2024, where far-right anti-immigrant groups picketed asylum hotels, causing countrywide disorder, following the murder of three girls in the Merseyside town]. There’s a large Bangladeshi community here, and after the riots, members of that community approached us. I know people often think of Camden as a very diverse place but when you actually speak to colleagues, you quickly realise that racism is still a daily reality for many. We’ve also recently experienced something we haven’t seen in years: a spate of far-right activity, including stickers and leafleting popping up around Camden. It’s the first time in a long while that it’s resurfaced in our area.

Where does your solidarity with Palestine stem from?

PAUL: I’ve been involved in the cause for Palestine for 20 to 30 years now, attending demonstrations and supporting the Palestine Solidarity Campaign. That kind of visibility really matters, especially because Keir Starmer’s constituency is in Camden. The solidarity has always been there. I think for many of us on the left, our solidarity with Palestine is rooted in earlier struggles. For me, it was the anti-apartheid movement. I know it’s become a bit of a cliché to quote Mandela saying, “Our freedom is incomplete without the freedom of the Palestinians”, but that message truly resonated. A lot of people on the left took that seriously.

Have you ever been arrested for your activism?

PAUL: I got arrested for collecting for the miners, [a charge] which was dropped later on. I was arrested on a picket line. We were accused of trying to run a lorry off the road in Wapping, which was absolute rubbish – we were leaning out the window giving the v‑sign!

Shezan, what was your political awakening?

SHEZAN: I was born here but grew up in Hyderabad, India, in a fairly secular area attending a secular school. But during my early teens, things began to shift. As [Prime Minister Narendra] Modi rose to power [in 2014], tensions between Hindus and Muslims escalated, and the sense of shared community faded. When I moved back to the UK, I carried that experience with me. Even though I’m not a practising Muslim, having a Muslim name made me cautious. I was always wary of engaging politically – we even had to be careful about what we said on the phone with family abroad. That sense of being watched, of needing to self-censor, never fully left.

Tell us about Camden United Against Racism.

SHEZAN: In a weird way, I think I was more aware of racism after I met Paul. Before that, I’d always thought I [was] just imagining it. But then we’d go somewhere together and I’d see how people talked to me [alone] versus when they saw that I was with Paul. The difference was shocking. People would say things like, “I can do this for you,” or, “You’re shy, so I’ll speak on your behalf.” But I’m not shy. Often, it felt like they assumed they could speak better [than me] simply because they were white. That’s part of why we set up Camden United Against Racism.

Is it ever hard to sustain hope?

PAUL: Yes, but you remember the battles you won, [notably] seeing Mandela [freed]. SHEZAN: There were times in history where we thought: “This will never end. It will be like this forever.” But it wasn’t. There is a light and people just have to push through it rather than giving up.

Rajan Naidu, 74, Birmingham

Activist

PROTEST HISTORY:

- Amnesty International member

- Anti-arms trade protests

- Friends of the Earth member

- Extinction Rebellion, 2019 onwards

- Iraq war, 2003

- Just Stop Oil protest at Stonehenge, 2024

Do you come from a political family?

We moved here from Belgaum in India when I was two. I came from a very patriarchal family. I had a really rough time growing up because I, like my father, like to argue and we never backed off. He wasn’t an activist in the sense that I am, but his spirit was very much that of an activist of social change – if you know about something that’s wrong and can do something about it, you do it.

What drew you towards Extinction Rebellion?

I was observing from a distance in 2019. I went to Trafalgar Square, where there was a huge rally. At one point, they asked everyone to form small groups and share observations. I spoke to the person next to me and said: “When I look at this crowd, I see mostly white people, a few brown and Black faces. XR [Extinction Rebellion] has been around a year now – it shouldn’t still look like this.” She said: “We’re working on it” I replied, maybe a bit sharply: “Not enough.” She asked: “Well, what would you do?” I said: “Each of these thousands of people has diverse friends – Black, brown, disabled, all kinds. If everyone invited just one friend who wouldn’t normally come, stayed with them and made it a social event, the crowd would look different next year. That’s how the movement grows, friend to friend, until it truly reflects our society.” Eventually she said: “Rajan, would you like to say that to the 5,000 people here?” From that moment on, I was in.

Do you feel like the right to protest has been on precarious ground before in history?

Yes, it has. It’s a constant human struggle. If you don’t use your rights, they’re taken away bit by bit until they’re gone. Every right we have – to work, rest, travel, have an identity, a bank account, for women to have equality – has been fought for. Nothing has ever been freely given; rights are won through protest and resistance, sometimes even through disruption. I only believe in peaceful civil resistance. I’d never harm anyone, and most in our movement feel the same. We want a peaceful society, and we won’t reach it through violence. We must be examples to each other and to those outside the movement. Standing up peacefully is the way forward.

Steve Fox, 59, Birmingham

Architect and model

PROTEST HISTORY:

- Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, 1980s

- Miners’ strike, 1984 – 85

- Anti-apartheid demonstrations, 1980s

- Poll tax, 1990

- Iraq war, 2003

- Extinction Rebellion, 2018

- Save the NHS, 2017

- Lift the Ban for Refugee Action, 2025

Are you from a political family?

Quite the contrary. My parents are almost completely apolitical. They’re quite conservative, working-class people. Around the age of 14, I realised my observations collided with my dad’s. I remember a conversation about immigrants and Iranians, and that must have been in the early ’80s. I heard things that didn’t feel right and then pointed out to him and his friends that they were being racist. Later on, I dabbled in student politics. But there was a massive gap between those times and more recent times in my political engagement.

Those recent times being?

Coming across career politicians in my life, I’d always felt suspicious of people who got involved in politics. I was more naturally inclined toward anarchist [structures]. But when [Jeremy] Corbyn was elected [Labour] leader [in 2015], it was obvious that it was more of a bottom-up movement, and that’s what he was try- ing to encourage within Labour. I felt young again, like my student politics had come back. That was a good thing. But we learned a lot about the Labour Party in that time, about the limitations of it and the corruption of it.

How have your kids reacted to your political engagement?

My kids are very active politically, I’m immensely proud of that. They gave me some good advice about what to do when you’re arrested. They move in activist circles, which are more aware of the consequences of interacting with police. We’ve learnt a lot from each other. I have a lot of faith in the youth and young people. I think kids these days are better informed, wiser and better organised.

How did it feel after you were arrested?

No regrets. Once I’d done it, it felt like a massive sense of relief that I’d done something, because there was this horrible feeling of going around the world not knowing what to do. The more of us do it, the more it will work. That’s the thing we learned when we were canvassing in the Corbyn times: if you didn’t show up, if everyone took that attitude, nothing would happen. It wasn’t about you as an individual. It was about you as part of a group.

[10] Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament — Protest at Greenham Common and Burghfield (2017), via Getty Images. [Accessed 5 Nov, 2025]

[11] End of the Miners’ Strike | Dramatic News Footage Captures End of Historic Confrontation (2025), ITN Archive.

[Accessed 5 Nov, 2025]

[11] End of the Miners’ Strike | Dramatic News Footage Captures End of Historic Confrontation (2025), ITN Archive.

[Accessed 5 Nov, 2025]

[12] BBC News | 07.10.2019 | Extinction Rebellion (2019), Extinction Rebellion (XR) UK.

[Accessed 6 Nov, 2025]

[13] Julian Assange supporters protest outside extradition hearing in London (2024), Guardian News [Accessed 6 Nov, 2025]

Valerie Milner-Brown, 73, London

Writer, activist and co-founder of political party Burning Pink

PROTEST HISTORY:

- Extinction Rebellion, 2019

- “Bring Down The Government” – Burning Pink mayoral campaign, 2021

- London mayoral candidate, 2022

- Action against NGOs for receiving funds from corporations and governments, 2022

- Action at HSBC Canary Wharf HQ for its fossil fuel investment, 2022

- Speaker at the protest for Julian Assange appeal hearing outside High Court, 2024

- Spokesperson for The Surge protest against the Africa Energies Summit, 2025

What drove you to join Extinction Rebellion?

Initially, I joined XR to recruit Caribbean and African people to the fight. I was met with three responses: 1) God will take care of everything. 2) White people created the problem, they can fix it. And 3) I can’t risk arrest because police treat Black people worse. Their responses pushed me to dive deeper into activism. I thought of the brave Black activists who inspired me growing up: MLK, Muhammad Ali, Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, Mandela, Marvin Gaye and the leaders who ended colonial rule in Africa. I joined the [anti-airport expansion protest] Heathrow Pause to show Black people we can do this – we’ve done it before. This was no time to cower before police brutality; the world stood at a precipice.

Tell us about your arrest in 2019 surrounding the Heathrow Pause campaign.

In April 2019, Theresa May declared a climate crisis but less than one week later she gave the go ahead for a third runway at Heathrow. We decided to shut down the airport by triggering a loophole in their security policy that a drone, even when flown only at head height five miles away from the runway, could force a shutdown, costing the airport and insurance companies millions of pounds in days. Two weeks before, we’d had two meetings with the Heathrow authorities, Heathrow police and their head of sustainability to discuss the reasons for the action and how it could be stopped. We explained the entire strategy to them. The only thing we didn’t tell them was exactly where we would be standing when we flew our toy drones. On the day before the action, I offered my home in London to host press interviews. There, I was arrested along with three other potential drone-fliers. I was driven to Holborn police station and kept in custody for two nights and three days. I didn’t know it then but now I understand the phrase “the ecstasy of revolution”, [inspired by Marxist theorist] Guy Debord. A feeling of being overwhelmed by your own courage to stand up to authority to try to save what matters most: a safe world. [Valerie was later found not guilty of conspiracy to cause a public nuisance.]

What would be your advice to young activists today?

After six years of non-violent civil disobedience and witnessing the public’s general apathy, I would like to share with young activists that we have to find a way to lead humanity away from mind-numbing, vain distractions. The revolution must begin inside ourselves. This is how, en masse, we can take on the billionaire class.