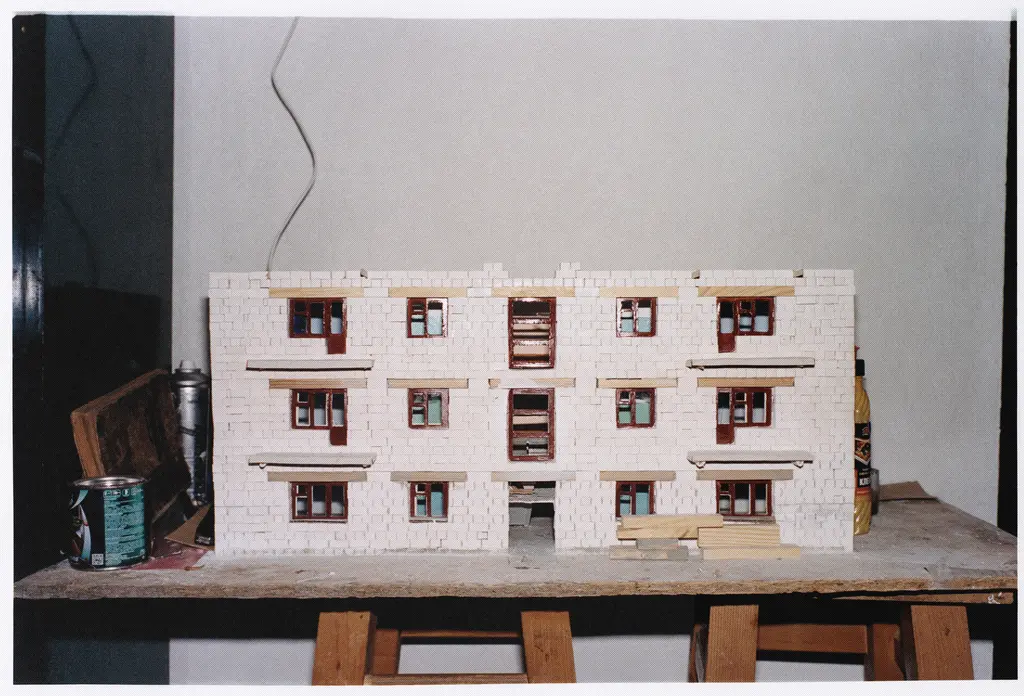

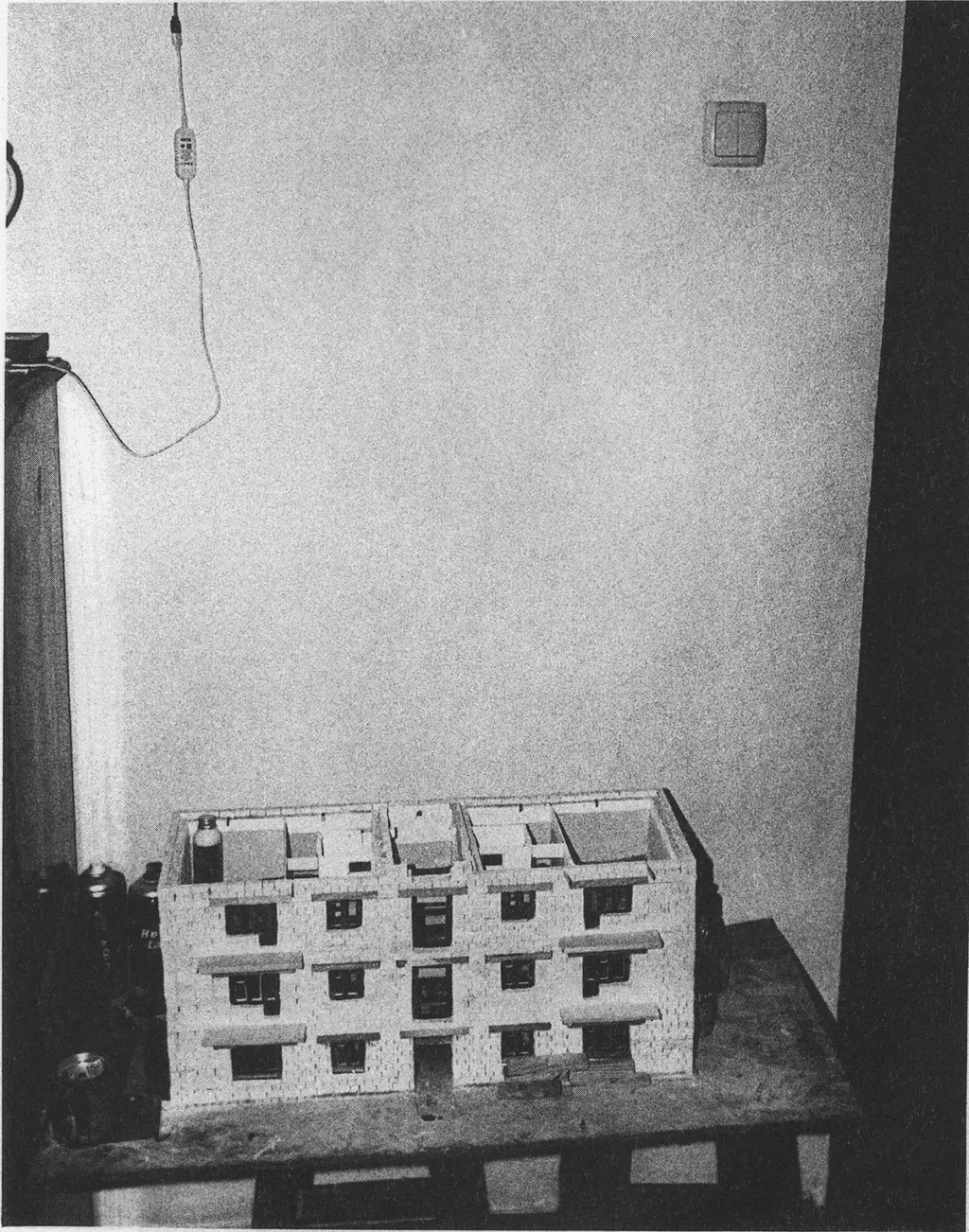

Diamond coating on a blade

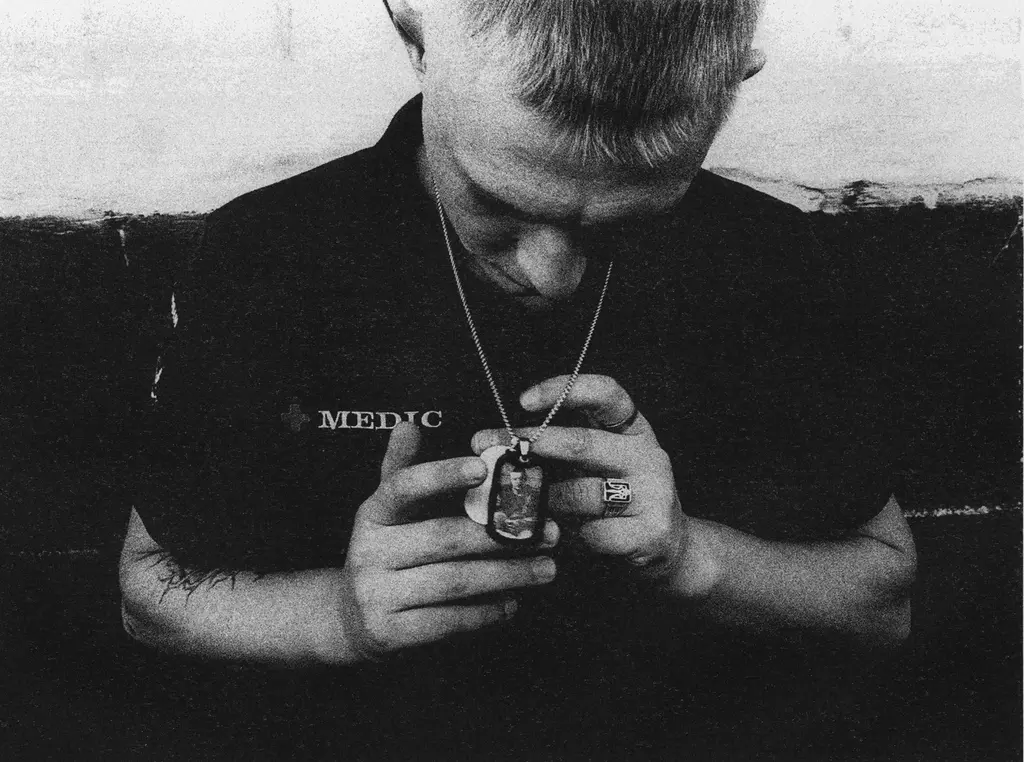

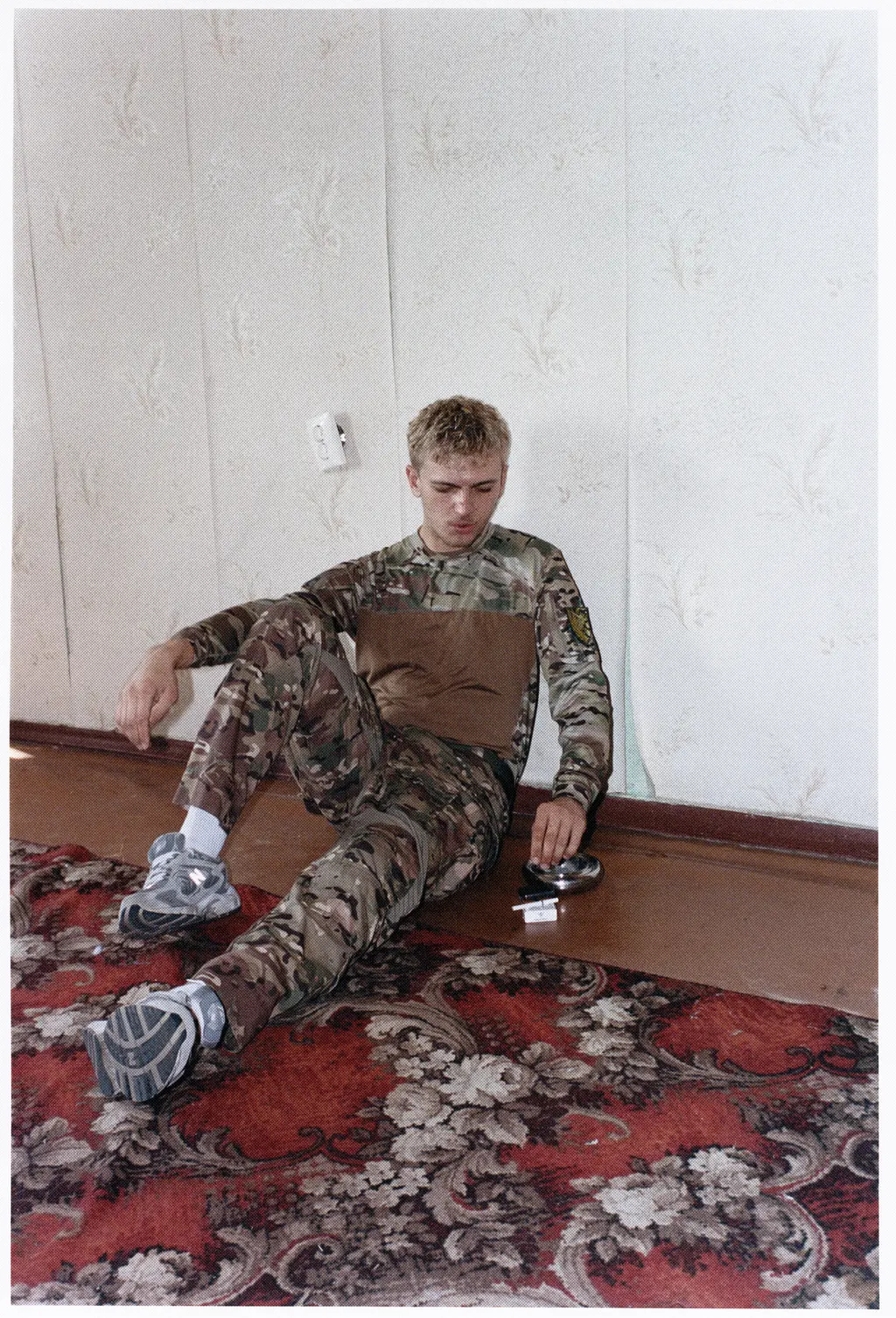

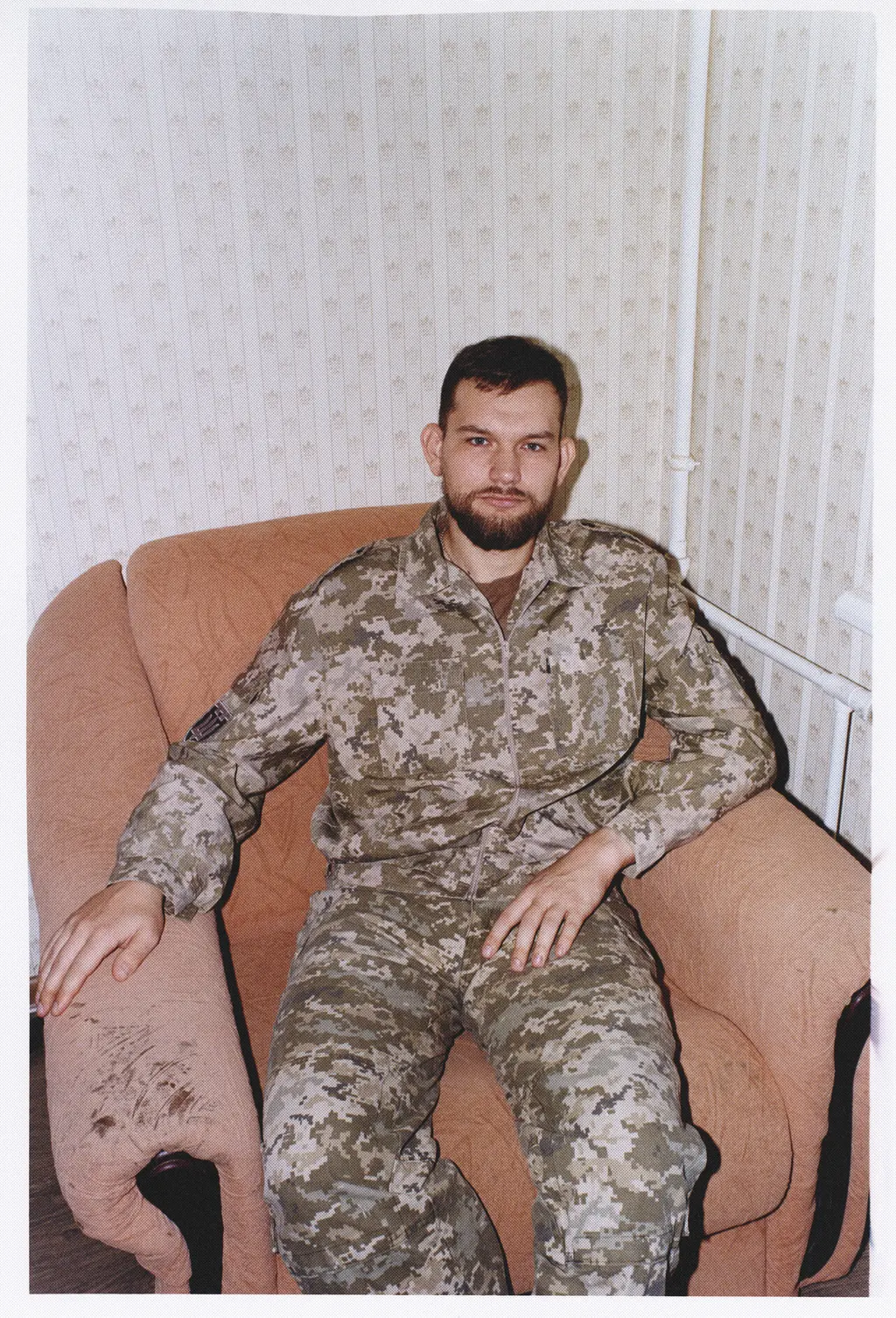

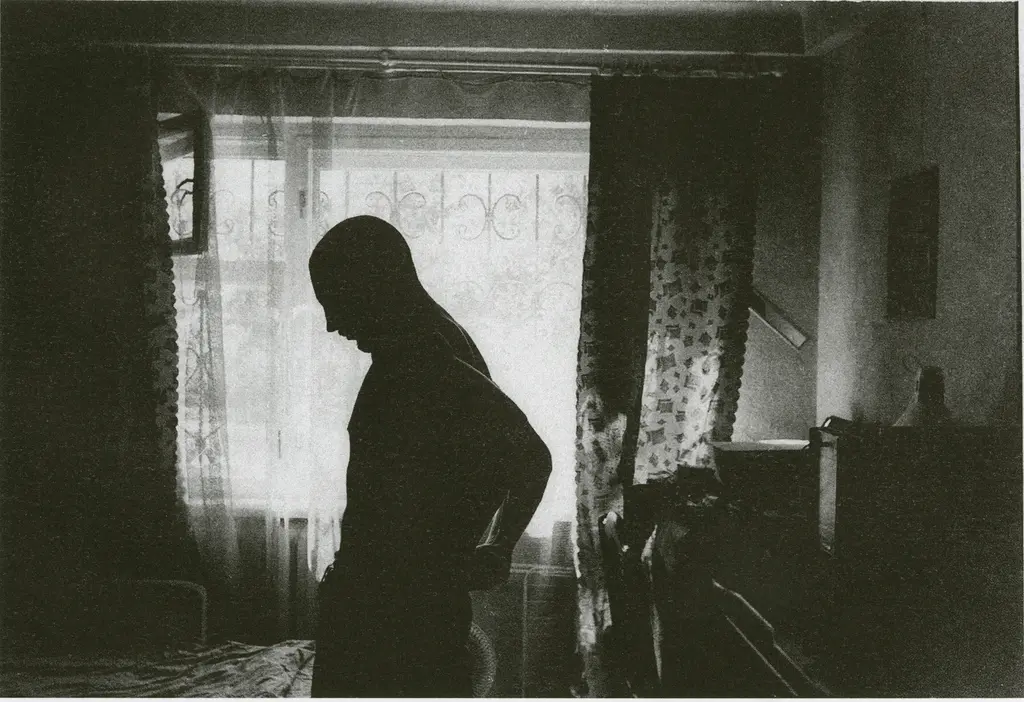

Oleksandr, 25

In a country fully mobilised against an existential threat to its existence, Ukraine’s queer soldiers are on the frontline of a fight for acceptance. Until recently, their presence and struggles remained largely invisible.

Society

Words: Serhiy Morgunov

Photography: Jesse Glazzard

Creative producer: Eugenia Skvarska

Taken from the winter 24 print issue of THE FACE. Get your copy here.

Some people woke to rumbling – maybe thunder, maybe fireworks, or so they thought. Others were jolted awake by calls from those who’d heard the noise and knew it wasn’t thunder. Then there were those who hadn’t set an alarm that morning, hoping for a rare chance to sleep in, not realising they’d wake to a world turned inside out.

For most, it was like something bottomless, heavy and silent. The news had warned them for months about a “possible full-scale invasion” but they brushed it off, didn’t believe it, couldn’t bring themselves to. They pushed the truth away until it became undeniable. And now: war. Suddenly, the word felt different. Not the kind of war you’d see in movies or read about in heroic stories; not even the distant conflict in the east of the country they’d lived alongside for eight years. This was their war. Something heavy, foreign, spoken with trepidation – its meaning foggy and unreachable, like invisible forces attacking without warning, motives and reasons hidden.

A week before Russia’s all-out assault on Ukraine, Oleh (for this article, I’m only using first names and omitting identifying details) had spoken to his grandmother by phone. They talked about what he’d do “if war broke out”. Half-joking, he told her: “I’ll go to the village, sit in the cellar and live off canned food until it’s over.”

Then came 23rd February 2022. His first-ever date at a gay club – and, as it would turn out, his last date with that guy. “Of course, I got totally wasted in the club,” he remembers of his night out in Kyiv. They said goodnight and went their separate ways. The next morning, he woke to dozens of missed calls, mostly from his best friend. He finally picked up, joking with exasperation: “Have you lost it, calling me at this hour? Everyone knows I love my sleep.” But instead of laughter, he heard something else. “Oleh, the war has started,” she said, her voice breaking with tears.

He got up, went to the kitchen and found his mum making breakfast, about to take the dogs out. He asked if she’d heard the explosions. She nodded. “I thought it was thunder.” “No,” he said. “It’s war.” She turned on the TV, and there it was, on every channel. She went to the window and started to cry. That was the moment that got to him. “I can’t stand seeing my mom cry,” he says. “That’s when I began to understand that maybe we were actually in deep shit.”

Oleh grabbed his dog, Balu, and headed to the shop for a beer to clear his head, “to take the edge off and figure out what to do next”. As he stood in line at the checkout, holding two bottles, people around him were buying essentials: salt, matches, candles; needs unchanged since the second world war. By the time he returned home and saw his mother waiting at the window, his decision had been made: “I have to join the fight.”

Other guys his age were already in the thick of it. For Oleksandr, who has been a soldier since 2019, fighting in a war hitherto confined to Ukraine’s east, the day the invasion turned full-scale started early, with a 4am alarm at a checkpoint near the “frozen” frontline east of Mariupol, southeastern Ukraine. A quick call to his mum: “Are you safe?” Her voice was steady but tight. “Everything will be OK,” she replied. “Everything will be OK,” he echoed, hoping to believe it. And then the order came: “We’re staying to defend Mariupol.” Oleksandr’s tasks were to evacuate the wounded, transport fresh troops to forward positions and manage logistics.

“War is a struggle,” he remembers thinking. “For loved ones, for land, for life.” But the deepest pain lay in human losses. “Just moments ago, we spoke, he was running beside me… and now he’s ‘cargo 200’,” he said of a comrade, using Ukrainian army lingo for a fatality. “That’s the worst of it.” Despite everything, there was adrenaline. The feeling of fulfilling a mission, of being useful, needed. That rush ended after his injury at Azovstal, one of the world’s largest steel production facilities, which became a fortress of Ukrainian resistance during the siege of Mariupol. “A flash – white and yellow. Seconds without sight, without sound. I thought I’d lost my eyes. Then I remember screaming. Shock, pain. The guys dragged me to the shelter.”

The Russian invasion drove young people from every corner of Ukraine, from every kind of life, to choose their part in the struggle. Before the war, Vlad owned a cafe in Kyiv. “My business was just coffee. Everyone wants their coffee in the morning,” he recalls, adding that he had dreamed of opening a pastry shop where guests could watch desserts being made. Even a year into the full-scale invasion, his cafe kept running until Vlad, seeking new ways to help, decided to join the service. Many military personnel visited his cafe. Vlad took advantage of this, asking if their unit needed a medic.

“Back in 2014, I was drawing pictures for the soldiers and our school would send them to the front. Now, I’m the one receiving those drawings from children”

Vlad

He’d first gained medical skills years before the war when, looking for any work he could assist with, he rented a room in a Kyiv apartment shared with a doctor. He cared for bedridden patients, learning hard-won lessons hands-on: Natasha, with brain cancer; Oleg, with stomach cancer. Each endured pain that never left, fighting for every breath. Oleg died in his arms when his lungs finally failed. “It teaches you to have nerves of steel,” Vlad says, “but not to grow hard.” Now he is a combat medic, but he still hasn’t learned to keep his distance. He grows attached, feeling each loss as if it were his own. “My greatest weakness,” he admits, “is also my greatest strength,” realising that even now, he remains alive and deeply human.

This generation, like all others, did not get to choose its time. Oleh, Oleksandr and Vlad are all 25 now. When the full-scale war began, they were just 22. Born in the last year of the past millennium, they arrived in a world where dreams of freedom for Ukraine were just beginning to take root but were not yet shielded from the weight of old traumas – of a totalitarian and colonial past. After generations marked by suffering and loss, it seemed they might be the ones to break these cycles. But now they find themselves living out the destinies of their grandparents, carrying the same burden of war – but with an added pressure.

Vlad

Pavlo, 23

Pavlo

All three men are queer. All three have been thrown into a fight for national survival. But they’re also on the frontline of another fight: that of civil rights, tolerance and acceptance. The aggressor for these young Ukrainians is an imperialist nation with a recent history of homophobia and generalised anti-LGBT+ feeling.

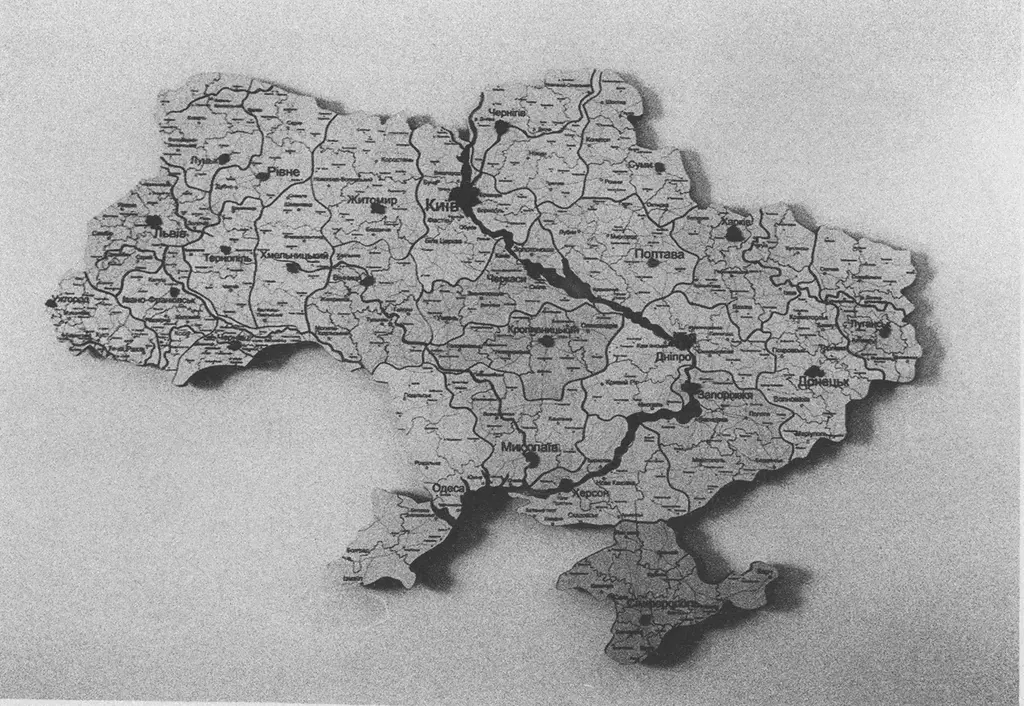

And even amid the horror of war, the persecution feels real, specific, targeted and extra cruel. Human rights organisations report that LGBT+ people in Russian- occupied territories face systematic persecution and torture. During Russia’s occupation of Kherson, there were documented incidents of violence: a volunteer from Pride Kherson was tortured in a basement for two months. Two men were detained after Russian soldiers found gay dating apps on their phones, and one was taken to the woods and shot in the leg. In occupied Donbas, discriminatory laws have been enforced, LGBT+ organisations dismantled, the community driven into exile.

In Crimea, the situation has deteriorated in the 10 years since Russia invaded and annexed it: restrictions on freedoms, violence and persecution were forcing LGBT+ people to flee long before 2022. These accounts expose the systematic human rights abuses facing LGBT+ individuals in occupied territories, where torture, unlawful detention and physical violence place their lives in constant jeopardy.

Ukraine, by contrast, is a Westernised liberal democracy. Certainly it had its own history of homophobia, particularly in the early years following independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. But even in wartime, as many of its most active citizens have been mobilised or lost in the conflict, it retains a strong civil society, modern culture and all that accompanies it: a vibrant arts scene, rave culture, a diversity of expression.

Via a trusted network of contacts on the ground in Ukraine, and with utmost care for everyone’s safety, I was able to speak to a group of young men for whom, for almost half of their lives, their country has been at war – and for whom, arguably, the stakes are even higher.

Dmytro, 32

Oleh

I remember it all clearly,” Vlad recalls of 2014, the year Russia invaded the Crimean Peninsula; sovereign Ukrainian territory. “Back then, I was drawing pictures for the soldiers and our school would send them to the front. Now, I’m the one receiving those drawings from children. Many men in my unit are over 50, and when I tell them I once drew these for them and now get them from their kids, some of them even tear up. Sometimes, the older ones say: ‘Well, back in my day…’” he continues. “And I reply: ‘And here I am, in my day, fighting alongside you.’”

Older men often tell him he has no place at the front, that he should be living among civilians, experiencing his youth without the shadow of war. But Vlad holds firm: “I’m here in the military, cleaning up your mess.” For him, the war is a reckoning; a payment for the choices and inactions of previous generations. Now, as he puts it, the young are forced to pay the price of this inheritance.

Although Ukraine’s leadership has limited the mobilisation of youth aged 18 to 25, many young people have still volunteered to fight. They are different from generations raised under Soviet fears and restrictions, distancing themselves from a past that imposed limits, powerlessness and pressure. “My generation is about individuality,” Oleh says. He feels that today’s youth seek not only national freedom but the right to self-expression, self-discovery and self-development.

This makes their aspirations fundamentally incompatible with Russia, a country that cultivates entirely different values. In modern Russia, Oleh notes, criminal prosecution for dissent, entrenched homophobia and the suppression of civil rights flourish – a drive to pull society back into control and repression. Consequently, Ukraine’s young generation fights not only for territory but for the right to exist in a world that honours human dignity. “There are so many young people fighting now,” Vlad continues. He recalls, on his first deployment, being surrounded by guys aged just 19 or 20. Many of them are already gone. “Two friends – one missing, the other killed, at 23 and 22.”

In the first brutal month of the war, fighting near the small town of Hostomel 10km northwest of Kyiv, new recruit Oleh felt artillery strike dangerously close. Reality sank in: his chances of survival were razor-thin. “Mortar fire, about 30m away,” he recalls. “I thought: ‘This is probably it. I’m staying here, going to die here.’” In that moment, he decided to open up, posting a tweet outing him as a gay man in the military. “Not a single hate comment came through – only support. Women wrote to me: ‘You’re our falcon. Take care of yourself. We don’t care about your orientation. We’re proud you’re fighting.’”

Oleh, 25

Before that post, Oleh hadn’t even considered how his sexual orientation might be perceived in the army. “Back then, you only had three thoughts: eat, sleep, don’t die. There was no space for anything else,” he remembers, reflecting on those gritty early days of the conflict in Kyiv Oblast. Only after the region was liberated did he decide to come out directly to his comrades, too. Still, he was careful. “I wasn’t going to go around announcing I was gay. I only mentioned it if someone asked about a girlfriend or wife.”

The first time he did, it was casual, and the reactions of his older comrades often amused him: “Wait – you’re gay? How does that work?” Oleh had a quick response, the kind of humour you need in a war zone: “Guys, the heels and dress didn’t fit in my bag this time, but maybe next time I’ll bring the feather fan.” His irony cut through the tension, and he was accepted without prejudice, even in the trenches.

Since then, Oleh has committed to breaking stereotypes, to showing that gay Ukrainians are part of this fight. “I want to help build a modern, inclusive, tolerant Ukrainian society,” he says. “That’s one reason I wrote that post. If I’m going to die, I want to leave something good behind.”

After the Battle of Kyiv in the first months of 2022, Oleh’s path led him through Kharkiv Oblast and then to Bakhmut. Relentless Russian bombings levelled the city, and he and the remnants of his unit withdrew to Sumy to recover before heading south to fight in Zaporizhzhya. His combat journey concluded there, ending with his demobilisation in the spring of 2024. Everywhere he went, his comrades accepted him the same way.

“I’d start by getting to know people, waiting for someone to ask about family or relationships. They always took it in stride. In my opinion, if you’re a decent person, orientation doesn’t matter. The main thing is to do your job well. Don’t screw up, act right and people will respect you.”

Hryts, 36

Dmytro

In his corner of the battlefield, Vlad was forced to be even more bluntly practical. He and his comrades were huddled in a trench during a brutal Russian assault. “We had no cover, nothing,” he recalls. “I told the guys then: ‘If we die here, I don’t want to leave anything unsaid.’ I’d been wanting to say it for a long time. So I said: ‘I have a different sexual orientation.’” One of them shot back with a nervous laugh: “What, you’re a faggot?” Vlad didn’t flinch. “No, faggots are the ones we’re fighting.” He was scared of taking a risk – everyone around him, of course, was armed and on edge – but his admission was met without judgement. “It was a relief, even for me. Hiding it was exhausting.” They all survived that day, and though they remembered what Vlad had told them, it never became a big deal. “They know, and that’s that,” he says, surprised by the ease he felt. Even in a trench, fearing for his life, he could be himself.

Naturally, like society as a whole, not everyone was tolerant. Ironically, it was the new recruits who were often the most problematic. One, after catching whispers about Vlad’s orientation, started making cocky remarks. But the others quickly “shut him up”, and the commander drove it home. Drawing his pistol, he fired a shot at the ground near the new guy’s feet. “When Vlad gets back from the post, I’ll give him this gun, and he’ll shoot you in the leg. And I won’t stop him. So keep your mouth shut.”

It worked: the new recruit clammed up and even started asking questions, trying to understand. “Isn’t it better with girls?” he ventured. Vlad grinned. “Who told you that? I’ve been with women, too.” The guy hesitated, “I don’t know… that’s just what people say.” With a smirk, Vlad replied: “Oh, it’s ‘what people say’? Well, I’m the new sultan, here to change all that.” By the end, the tension was gone. They even became friends.

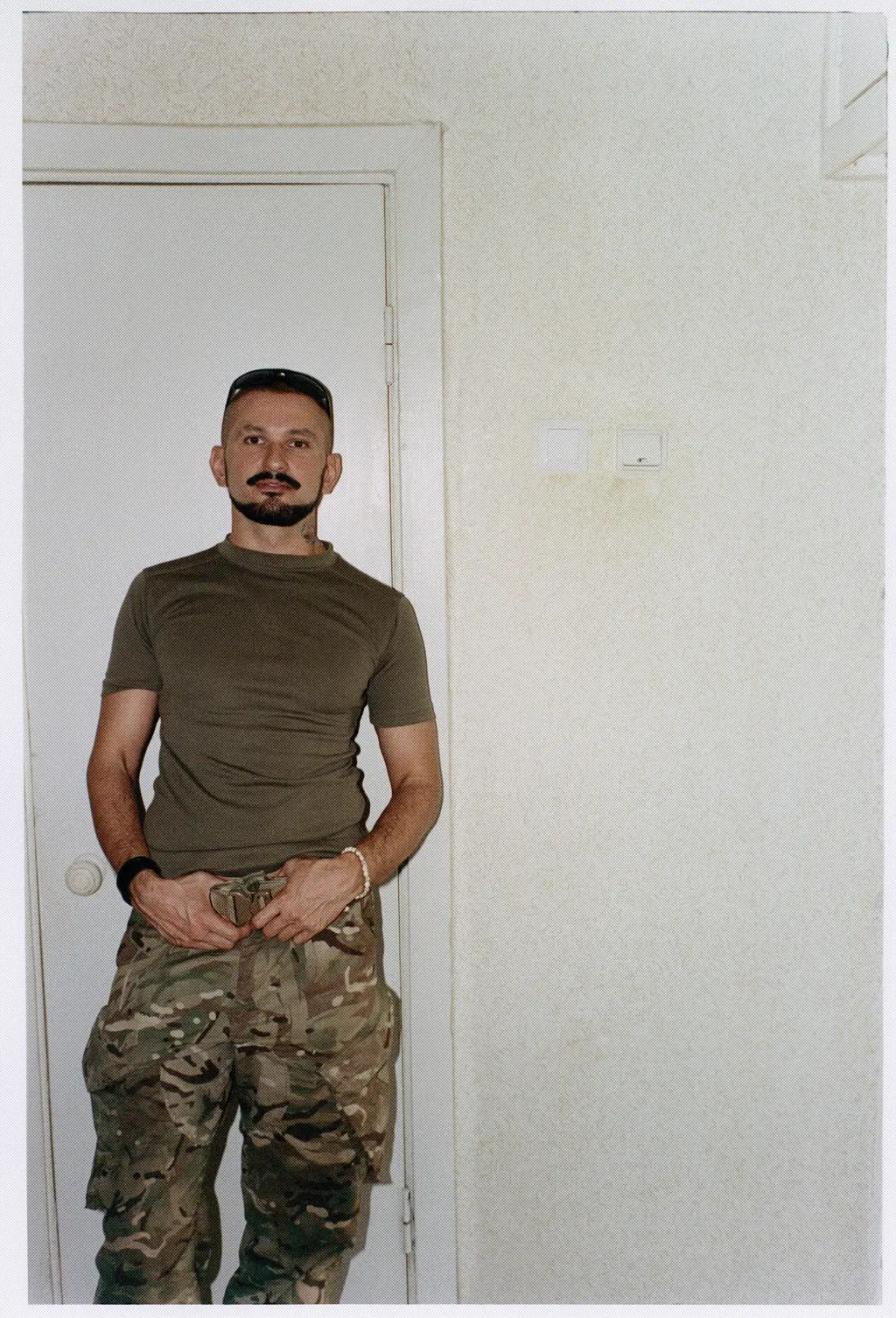

Viktor, 38

Oleksandr recalls his first moments after being wounded. He was dragged into Azovstal’s underground hospital, known among the military as “Zalizyaka” or “The Iron One”. “I was conscious the whole time, and soon enough, the pain hit hard. My jacket had melted into my back from the hot shrapnel. The heat burns through fabric, it melts, and plastic fuses with skin. That’s how you get those burns.”

Medics extracted shrapnel from his head and legs and dosed him with what few meds remained. Some pieces still lodge in his back to this day. “No stitching – others needed surgery more urgently. The city was surrounded; no reinforcements, no meds.” That’s when he first felt it: the cold fear of death.

The bunker was a harsh place, dimly lit by fluorescent lights, with an open operating area where everything was visible. “Not the most pleasant place. Wounded guys lay everywhere. Some were just screaming in pain.” Filth, unsanitary conditions, the stench of rotting flesh – antibiotics had run out and wounds refused to heal. “Some of the guys had 90 per cent burns,” he says. The ventilation barely worked; keeping light in the operating room took priority. “We were short on everything – food, vitamins, water. It wore everyone down, wounded or not. All I could think was that I didn’t want to die. I wanted to live.”

“If I die, I’ll die as a gay man. And if I survive, I won’t hide it anymore”

Oleksandr

That, unfortunately, lay in the hands of the enemy: Oleksandr’s unit were forced to surrender. On 20th May 2022, Oleksandr and those who could walk left Azovstal, carrying severely wounded comrades on stretchers. By then, he could move on his own, no longer needing support. Russian soldiers conducted a quick search before loading them onto buses to Olenivka, then Horlivka, and finally Taganrog, deep behind enemy lines.

It was in captivity that Oleksandr first came out to his comrades. “What was there left to fear? I thought the worst was already behind me,” he explains. These men had become incredibly close to him, and he didn’t want to hide from those he’d shared the battlefield with. “I wanted them to know everything about me so I wouldn’t have to hide from anyone.” To his relief, he encountered not a hint of homophobia. He had already come out to his mother, while he was injured in the depths of Azovstal’s underground. “If I die, I’ll die as a gay man. And if I survive, I won’t hide it from her anymore.”

Roman, 27

Viktor

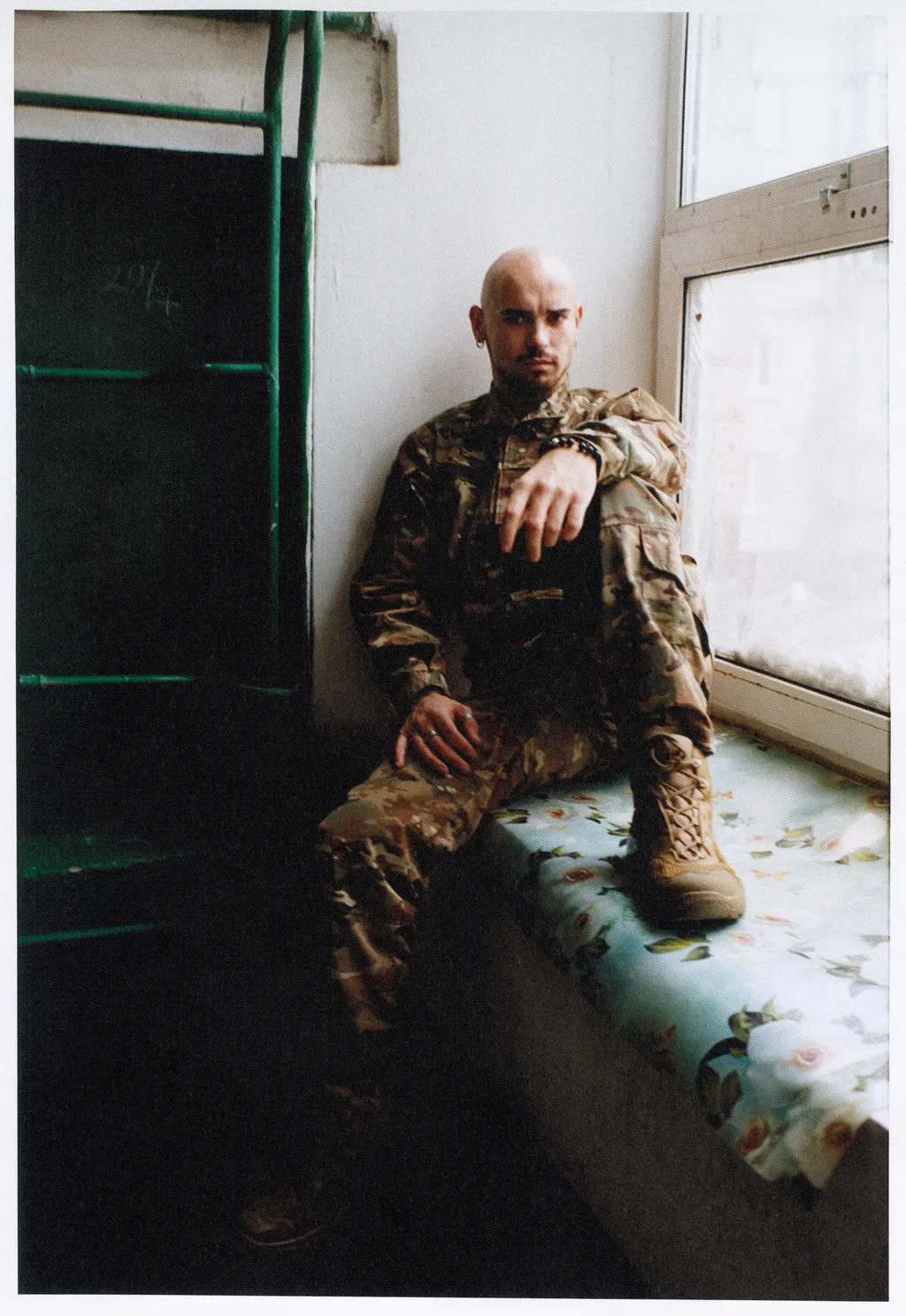

For Oleh, Oleksandr and Vlad there were, helpfully, trailblazers who dared to reveal themselves to their military comrades, carving a space for trust amid the strict codes of brotherhood. Viktor, 38, is a two-time veteran and a member of the previous half-generation who joined the war in 2014. He was among the first members of the Ukrainian military to openly declare his sexual orientation, coming out in 2018. Though it was after he left the Donbas volunteer battalion. “Back then, I faced the full weight of disdain for coming out, the rejection of me as a veteran-volunteer, as a person with trauma,” he admits. That same year, Viktor founded an organisation, the Ukrainian LGBT+ Military and Veterans for Equal Rights. By the summer of 2022, the group’s symbol – a shield-shaped patch featuring a unicorn – appeared on military uniforms, a quiet yet powerful protest against the myth that there were no LGBT+ people in the Ukrainian military.

Despite his personal challenges, Viktor has noticed an improvement in attitudes. “Every year, there’s progress. A shift in mindset, support from younger people. In 2018, when I came out, attitudes toward LGBT+ people were predominantly negative. But in surveys from 2023 to 2024, 60 to 70 per cent of Ukrainians opposed discrimination against LGBT+ people.”

Viktor

In Ukraine, same-sex relationships were decriminalised upon independence in 1991, yet social acceptance of the LGBT+ community remained a struggle. During the 1990s and early 2000s, homophobia was prevalent: public shaming, bullying and physical attacks; even murders motivated by hatred. Queer people were often seen as “exotic” or diseased – a legacy of Soviet stereotypes. The fight for identity has become part of the values Ukrainians now defend on the battlefield.

Indeed, for Oleh, the war has been beneficial for how Ukrainian society feels about queer people. He compares it to how his own attitude toward himself had been before the war. “The biggest factor shaping my view of the world was the fact that my own internalised homophobia walked in step with me. For a long time, I couldn’t accept myself and was certain society wouldn’t accept me either. But the war has changed attitudes toward LGBT+ people: people have seen that we fight, we die, we take part in combat. Comrades who once saw gay men as caricatures realised we’re diverse, that gays can be masculine, that it’s not just feminine men.”

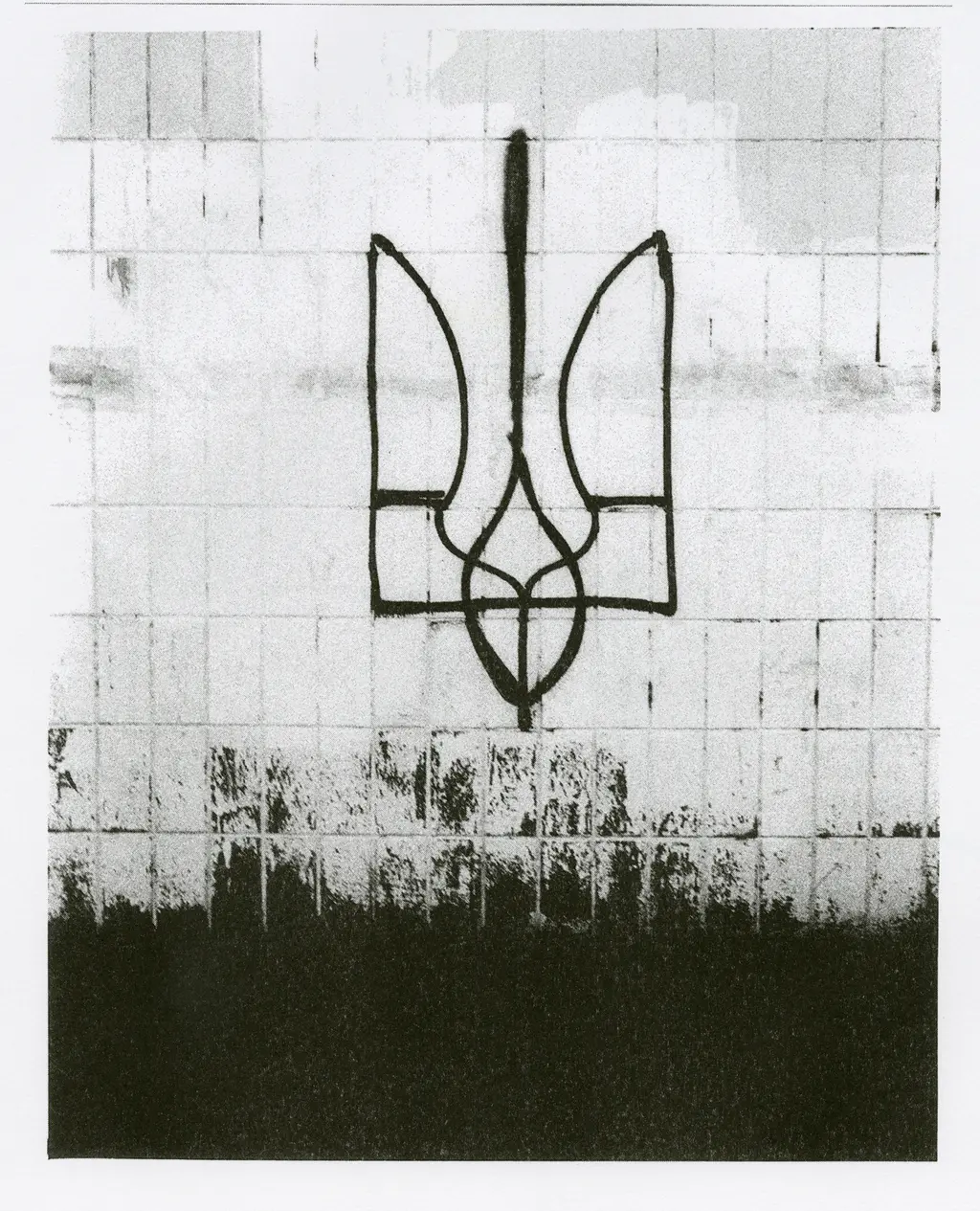

Viktor, his service spanning a decade, sees this war as being about more than territory. “This is probably the first war where so many openly LGBT+ soldiers are fighting on the frontline,” he says. “That in itself is a sign: we’re fighting not just for borders, but for values. We’re like a diamond coating on a blade – the first to hit this threat, cutting through metal.

“We’re on the boundary between a world of values and an anti-world,” he continues. “Russia and its allies – North Korea and Iran – are an empire trying to destroy the very concept of human values, crystallising into a sinister force, anti-matter, devoid of ethics.”

Hryts

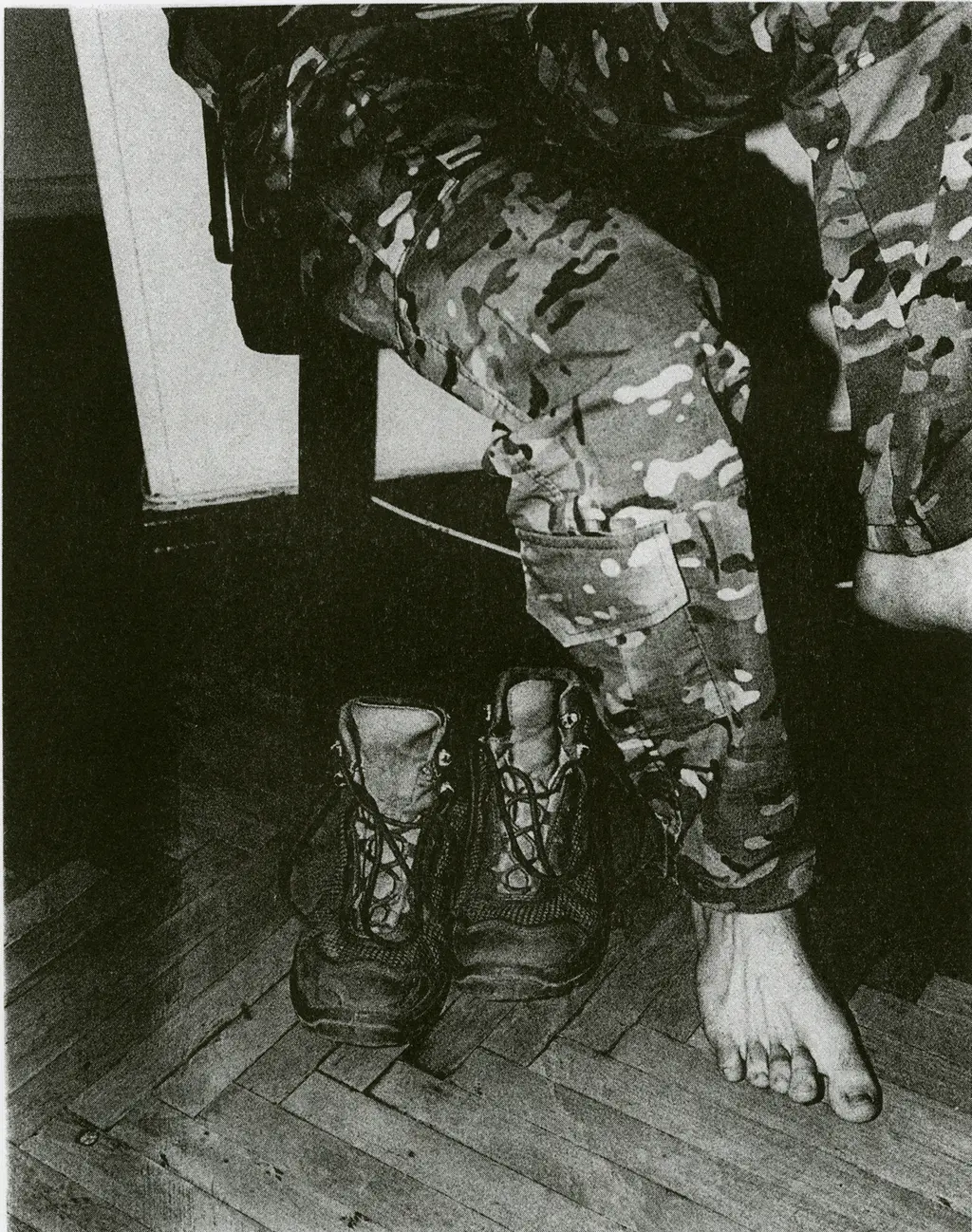

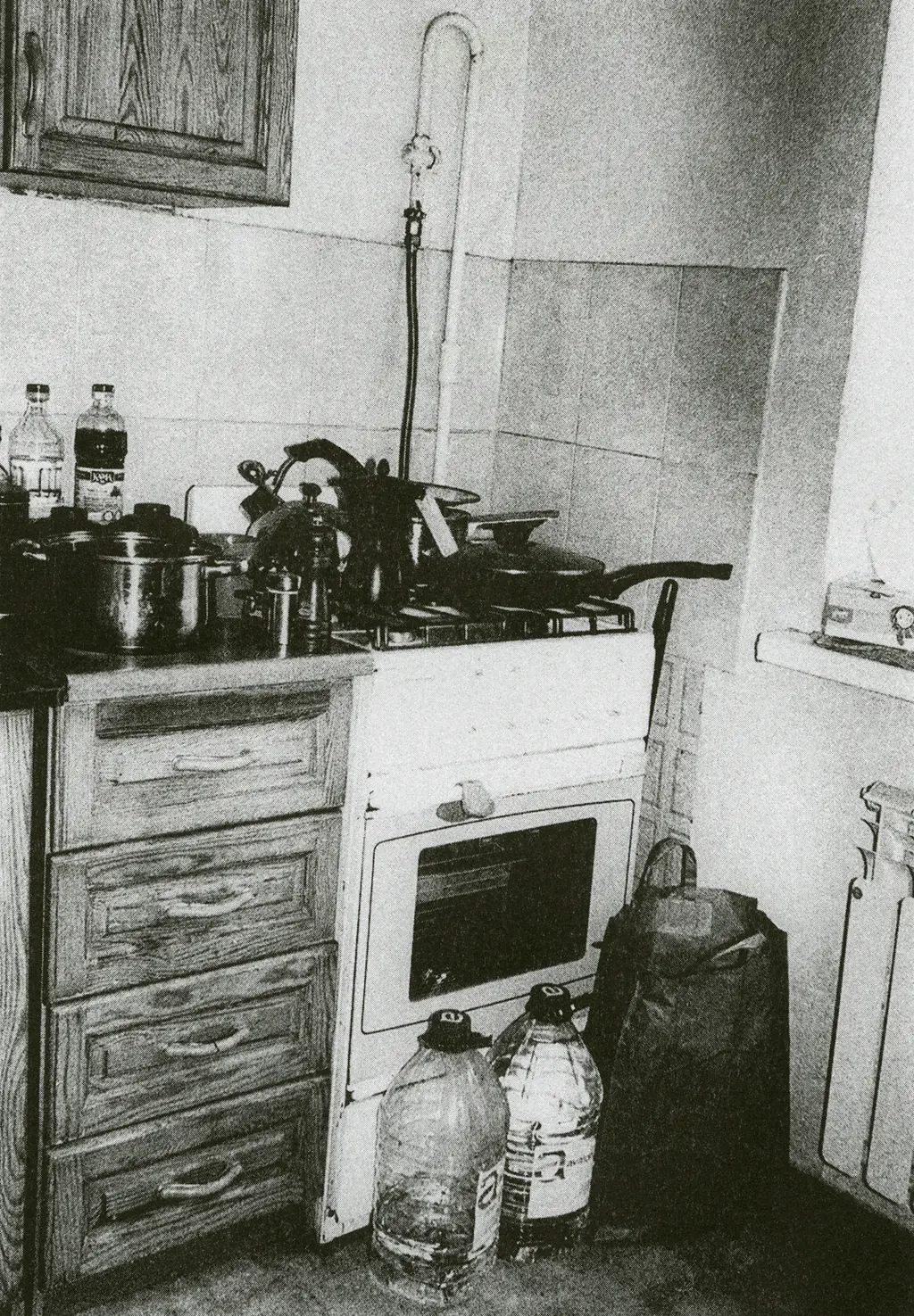

But the succour of knowing you’re fighting for a cause – national, personal – can only go so far. Vlad still wears a military tag with a photo of his lover. He and Ruslan’s relationship began in the east, amid the war. Their romantic world was unassuming, but it was real to them. “The guys knew about us, and they didn’t mind that Ruslan and I shared my room. Their commander would joke, “Whatever you’re doing in there, keep it down,” and Vlad would laugh back: “Commander, you’re welcome to join us.” The commander would wave it off with a grin: “No, no, I’ll pass on that.”

Ruslan was always there to meet him when he came back from the front on leave. “He’d text me the night before: ‘Can I borrow your car keys to go to the store? ’Cause I know you’ll want a beer when you get back,’” Vlad remembers with a smile. Every time, Ruslan would be waiting.

Their happiest moments were in the car at night. “We loved late-night drives – we’d get in the car, drive far outside the city, crank the music and sing along.” They’d pull over on a hill, open the sunroof, look at the stars, put on cartoons. “We’d sit in the back with a beer, just quiet, watching. That was our romance – the road, the stars, our own little world.”

Then, early this year, “we’d planned to go to his place for his birthday, to meet his parents. We’d even taken five days’ leave,” he recalls. But on 2nd April 2024, seven days short of his 22nd birthday, Ruslan was killed by a rocket-propelled grenade. They had been together for only six months. “It’s…” begins Vlad, fighting back tears. “Damn, it’s hard to even think about.” Every weekend, Vlad visits Ruslan’s mother in Kyiv, who greets him not as a guest but as family. At the funeral, she addressed the gathered mourners. “You’ll be my Rusik now,” she told Vlad, deploying the diminutive of Ruslan.

Roman

In the midst of society’s slow but undeniable progress, LGBT+ military personnel in Ukraine remain ensnared by entrenched legal and social obstacles. The absence of official recognition for same-sex relationships condemns their partners to a state of invisibility, denying not only the right to receive critical medical information but also the ability to visit in hospitals or make decisions about care. The absence of such rights extends to social benefits, pensions and the compensation that should accompany the loss or injury of a loved one in combat. It is a stark reminder of the systemic inequities that persist, underscoring the urgent need for legislative change. Despite widespread support among the public, the Ukrainian parliament hesitates, trapped in its own paralysis, unable to acknowledge the legitimacy of civil partnerships.

Before the full-scale invasion, Oleksandr had met someone, the owner of a small chain of barbershops in Mariupol. Their relationship blossomed despite Oleksandr’s service; as Oleksandr couldn’t leave sentry duty, his boyfriend would visit him at the checkpoint. He recalls those nights outside Mariupol, sharing dreams of a future together under the stars, talking about ordinary things, planning the kind of life most people take for granted. Then, as the war took hold, Oleksandr’s unit was redeployed. “When I was injured, we were still in touch. But when I told him we were surrendering from Azovstal, that was the last time we spoke.”

After 620 days in captivity, Oleksandr returned to a shattered world. Following a brutal three-month siege, Mariupol was captured by the Russians. Now his former love remains on occupied soil, where he’s opened a nightclub and accepted a new reality – one with seemingly no road back to Ukraine. Now, all they have left are memories. “To avoid hurting each other, to keep old feelings from resurfacing, we naturally stopped contact,” Oleksandr says.

Despite it all, the war has, with bitter irony, opened up a new sense of freedom for Oleksandr: “I know the cost of freedom through the lives of fallen comrades, friends, acquaintances and family. I’m sure these sacrifices weren’t in vain.”

Captivity and two years of confinement have given him a hard-won perspective. “Now I’m simply happy to be free, to do what I want and to be useful to those I choose.” In his dreams, he envisions a thriving Ukraine – in economic, social and cultural terms. “We need to create a new culture, one rooted in everything we’ve been through. After victory, once we exhale, we’ll be able to carry on with good work.”

Six months on from demobilisation, Oleh considers his military service, above all else, a test of resilience. And when his friends gather in a pub, he knows he fulfilled a duty that lets them keep that simple privilege. “I made my contribution so they could keep sitting there, drinking their beer in peace.”

As he sees it, his mission extends beyond himself. “In the service, I started to feel this was an investment in a peaceful life for future generations.” Oleh’s brother is 16; he was just 14 when the war began. “I fought so he wouldn’t have to. So that my children, his children, wouldn’t have to. Let me be the one to go through this.”

For Viktor, however, the veteran’s experience gives him a different, darker perspective. “The dead don’t need rights,” he says. “If Ukraine loses, our community – especially activists and openly LGBT+ soldiers – will face a stark choice: death, torture or escape.”

For him, this war is the last line of defence; a fight not only for victory but for survival itself. Despite the homophobia that lingers within Ukrainian society, he’s resolute: “Let us win this war, or at least halt the enemy. We’re wise people, and we’ll find our own way toward civilisational progress. But first, we must protect our country.”

CREDITS

CREATIVE PRODUCER Eugenia Skvarska CASTING Cat‑B Agency RISOGRAPH Page Masters POST PRODUCTION Ink Retouch SPECIAL THANKS Ukrainian LGBTIQ+ Military