Fashion in Transition: death, sex, drugs and the internet

Editorial in Detour Magazine, March 1997, © Photo: Davide Sorrenti

Antwerp’s MoMu Gallery tackles three decades of fashion in E/MOTION, exploring the defining socio-political moments in an exhibition that emphasises the transformative nature of clothing.

Fashion is best when it’s political, when the mood of the moment is reinterpreted into something a little otherworldly, beautiful or totally fucked up. Commenting on this is Antwerp’s MoMu Gallery who, after closing its doors in April 2018 for renovations, remerged this September with E/MOTION: Fashion in Transition – a stellar exhibition unpicking the politics, the clothes, the emotion and the motion (as in, movement) over three decades of fashion, told through key social events and designer interpretations.

The exhibition looks back at pivotal societal events – terrorist attacks, drug epidemics, the gender role evolution – questioning the role of the designer in responding to such moments and the cruciality of real-life presentations while unpicking the way fashion has evolved our ways of thinking through some of the most testing times. The Covid-19 pandemic, then, was the driving force for the exhibition, questioning whether fashion really can exist solely as a digital entity as it did until the recent return of fashion month in September.

“During the pandemic, we felt the need to make an exhibition that would really question the idea of emotion within fashion, because everybody was working remotely and in digital ways,” Kaat Debo, the exhibition’s curator, says. “Designers suddenly had to present their collections online and we were asking: can you evoke emotion without a fashion show? But also, we really wanted to come up with an exhibition that would move people.”

When you first enter the exhibition, you’ll find yourself head-to-head with a blood-red Comme des Garçons dress from SS15, roses and ribbons placed on the fabric as though bleeding down the body, a direct response to the then-recent terrorist attack in Paris. It’s compelling, terrifying and a fitting start to an exhibition that delves into all sorts of equally sensitive themes. Amongst them, drugs, disaster, virus, the internet, the body. And, within those themes, the male gaze, immediacy, financial turmoil, class, race and, yes, Covid-19.

It begs the question of whether fashion truly is reliant on an IRL presence. Fashion is best when it’s political, yes, and those statements are all the more powerful up close and personal – like in E/MOTION – when fabrics move, embroideries catch the light and cuts are 3D. It’s a link the exhibition makes when displaying Rei Kawakubo’s AW13 collection for Comme des Garçons. Seemingly always 10 steps ahead, they almost predicted a reliance on digital worlds in fashion, presenting garments that were flat and paper-doll, a commentary on the limitations of catwalk imagery.

“I think the future will be us moving to hybrid ways [of working],” Debo says. “Some designers say they really need a fashion show, others say they have discovered new ways of storytelling and that it brings in new opportunities.”

Helmut Lang, Spring-Summer 2000, ‘The Next Way’ editorial, Vogue Italia, March 2000, Model: Amber Vailetta © Photo: Peter Lindbergh

Cover image by David Sims, The Face, January 1998, ©David Sims /Art Partner, model: Bridget Hall, makeup: Linda Cantello

DRUGS

One of the most enduring of contemporary fashion eras (Instagram is awash), DRUGS explores the turbulence of politics in the early ’90s, when a deflated job market and pissed off Gen‑X youth birthed heroin chic, a minimal, violent and sharp contrast to the glossy excess of the previous decade. Waifish models, filthy sofas, greasy hair and zonked-out expressions made up much of the fashion photography of the time, thanks to photographers like Corinne Day, Davide Sorrenti and Vincent Gallo, and shows from Calvin Klein, Alexander McQueen and Vivienne Westwood. That and the emergence of grunge in the late ’80s and early ’90s, films like Trainspotting (1996) and the sheer hedonism of the decade’s drink and drugs culture led to designers responding through low-slung jeans, ripped, oversized sweaters and kohl-lined eyes that mimicked the effects of drug addiction and poverty.

It’s a style that still reverberates through shows and editorials today, although contemporary iterations are perhaps less nihilistic than its origins. Vogue Italia’s 2007 Super Mods Enter Rehab shot by Steven Meisel presented, literally, models off their faces being dragged into rehab. More recently, Raf Simons’ AW18 collection, Youth in Motion, was a direct commentary on excess and overindulgence, using Cookie Mueller and Glenn O’Brien’s early ’80s tragicomedy play DRUGS to illustrate T‑shirts and jumpers, as well as the 1981 German movie poster for Christiane F: Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo, which deals with child prostitution, drug addiction and death.

Kristen Owen, Helmut Lang backstage series, Spring Summer 1994, Paris, 1993, © Photo: Juergen Teller, All rights reserved

Dries Van Noten, Autumn-Winter 1997 – 98, © Photo: Ronald Stoop

VIRUS

Our fear of death was exacerbated over the past 24 months, when the Covid-19 pandemic ripped through the world. E/MOTION highlights not only this, but also past epidemics and pandemics that have inspired emotional responses from brands and designers, using sartorial efforts to encourage conversation. A key example is Martin Margiela’s T‑shirts that had “there is more action to be done to fight AIDS than this T‑shirt but it’s a good start” smartly printed on the shoulders. The text isn’t really readable, so curious passers-by have to ask what it says. Just like that, a conversation has started.

Italian fashion brand Benetton ran an advertising campaign in 1992, using an image of David Kirby, who lay in hospital dying of AIDS in 1990 surrounded by family members, as a means of selling clothes. It was controversial and quickly banned, with then-creative director Oliviero Toscani justifying the ad by saying the campaign came out of “meaning and issues that advertisers don’t normally want to deal with.” At the time of its release, AIDS was the number one cause of death for US men aged 25 – 44 and the ad had Kirby’s father’s backing, who saw it as an opportunity to raise more awareness.

The early ’90s also saw Walter Van Beirendonck’s rubber pieces used as condom-like protective shields to promote safe sex, with printed health messages appearing in his activist collections. Fast-forward to the past year’s collections and the face mask has become a symbol of health, safety and virus awareness for designers like Rick Owens and Virgil Abloh for Louis Vuitton.

CAMOUFLAGE

War, terror and fear in fashion have often been a direct response to terrorist attacks and increased militarisation in the western world, especially in a 21st century characterised by mass death on city streets.

Designers have often responded to the terrible aftermath of terrorism, both on the streets and on the news, through protective means – though it’s not always intentional. Hussein Chalayan’s SS02 collection, Medea, had hoped to confront the fashion industry’s wasteful history, using layered, fragmented upcycled garments.

But, instead, the use of camouflage prints and the tears and rips in garments had critics comparing it to the all-too-real images in the newspapers, making it a controversial collection that didn’t exactly seek that.

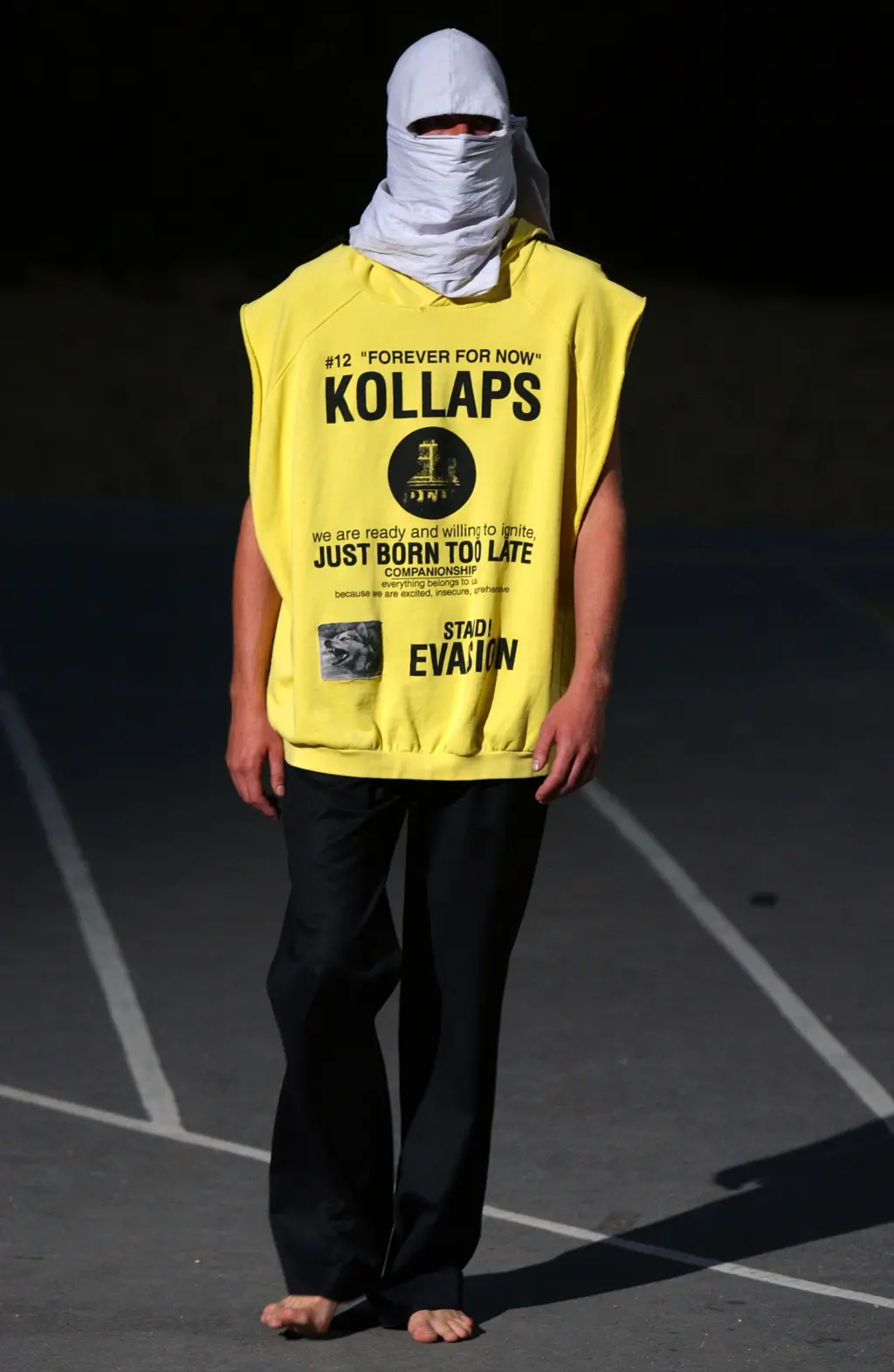

In that same season, John Galliano presented a camouflage evening dress with orange fabrics woven across the torso like a warning signal, while Raf Simons’ SS02 collection was a startling expression of fear, anxiety and cult mentality. Featuring balaclava-like hoods, camo bombers and double-breasted, Soviet-style army jackets, the show itself had models holding up flares, walking as though to protest the civil unrest felt of the time. Rather aptly (if also somewhat portentously), the collection was titled Woe Unto Those Who Spit on the Fear Generation…The Wind Will Blow It Back.

Raf Simons, Spring-Summer 2002, © Photo: Catwalkpicture

Exactitudes, 104 Commandos, Rotterdam/Paris, 2008, © Photo: Ellie Uyttenbroe

THE INTERNET

Before Instagram, sliding into DMs and the impending doom of the metaverse, the access to emails on home computers was a world-changing technology breakthrough. Then, in the early 2000s, came the mass adoption of mobile phones (that weren’t the size of literal bricks. See: Motorola Razr) and, with it, a whole host of problems – some good, some bad.

The rise of tech completely transformed the fashion ecosystem. On one simplistic level, fashion shows and reviews were soon no longer reliant on newspapers and magazines for their coverage.

Fast-forward to today, and designers and houses are utilising social media, knowingly tapping into a younger generation who are well-versed in the ’Gram. Back in 2000, when Jennifer Lopez wore “that Versace dress”, searches peaked to such an extent that Google Images was born – as was the powerful symbiosis between fashion and celebrity culture post-Millennium.

Prior to that, though, Jean Paul Gaultier was predicting the rapid pace at which tech was growing: his AW95 Cyber collection included cyborg-like digital prints, quickly grasping the sheer volume of tech in his futuristic approach.

More recently, Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons presented a fascinating take on the future. Her AW16 collection questioned whether intelligent robots would replace human labour and one day take over the world altogether – a question posed via pink latex featuring laser-cut shapes and armour-like body parts.

MINIMALISM

Ann Demeulemeester, Spring-Summer 1998, © Photo: Chris Moore

Minimalism came in the early ’90s after the gaudy excesses of ’80s fashion. It was out with shoulder pads, bold prints and permed hair and in with cleaner palettes, straight hair and lighter fabrics. As with to the rise of heroin chic, minimalism was a reaction to the financial turmoil of the early-’90s – a realistic approach to dressing, when excess seemed inappropriate.

Designers like Helmut Lang and Martin Margiela opted for white fabrics lightly layered, using ribbed fabrics on turtlenecks in cream, grey overcoats slung over white shirts, or ghost-like, wispy fabrics for dresses, as if almost to mimic a sense of disappearance. No longer was it necessary to overtly turn heads, but rather to seek comfort in the quality of these designers.

Similarly, after the re-emergence of thrill-seeking excess in the early-’00s through designers like John Galliano and the fame of celebrities like Paris Hilton – who often favoured bright colours and barely-there micro-skirts – Phoebe Philo introduced a new, Zen-like style of dressing for women when she took the helm of Céline. She, introduced sandy trenchcoats, adidas Originals’ Stan Smiths worn with jeans and palettes not straying too far from neutral colours and the odd olive green here and there.

At the same time, minimalism often strays from fashion’s idealisation of youth, utilising the influence of all ages. See: Helmut Lang’s ’90s campaigns with collaborations from photographers and artists Robert Mapplethorpe and Jenny Holzer. And see: Juergen Teller photographing a then-80-year old Joan Didion in a black shirt and large sunglasses. Minimalism, then, places emphasis on symbolic value rather than product.