Vivienne Westwood’s early, anti-establishment collections

Punk, 1970s

From pirates to royalty, tartan to tweed, the late, great designer's early collections remain some of the most powerful examples of her work. Here, fashion archivist Steven Philip talks us through the Westwood ensembles he's spent a lifetime building.

Style

Words: Brooke McCord

Photography: Jack Day

Styling: Danny Reed

Punk. Rebel. Radical. Revolutionary. Just some of the words that can be used to describe the genius of the late Vivienne Westwood and her canon of work. But you knew that, didn’t you?

From pirates to royalty, tartan to tweed, rubber fetish clubwear to mini-crinis and corsets, Westwood’s work was driven by a thirst for knowledge, messianic and meticulous cultural investigation, and a “make do and mend” mentality. Her London store at 430 King’s Road in Chelsea – through its many iterations: Let it Rock, Too Fast To Live Too Young to Die, Sex, Seditionaries and, finally, World’s End in 1981, a title the store still holds today – embodied the synthesis of her sartorial experiments with her ex-husband and collaborator, the musician, manager and fellow provocateur Malcolm McLaren. Later, her early-’90s collections solidified Westwood’s position as a serious fashion designer, tailor and couturier of substance, finally receiving critical acclaim from the fashion industry after years of being ignored by the more traditional institutions.

Westwood’s early ‘80s, anti-establishment collections merged fashion, sex, punk and politics, inspiring a generation and influencing everyone from Raf Simons and Rei Kawakubo to Marc Jacobs, who paid tribute to the late designer at his recent AW23 show. Over 40 years on, they still remain the most resonant examples of her work.

Punk, 1970s

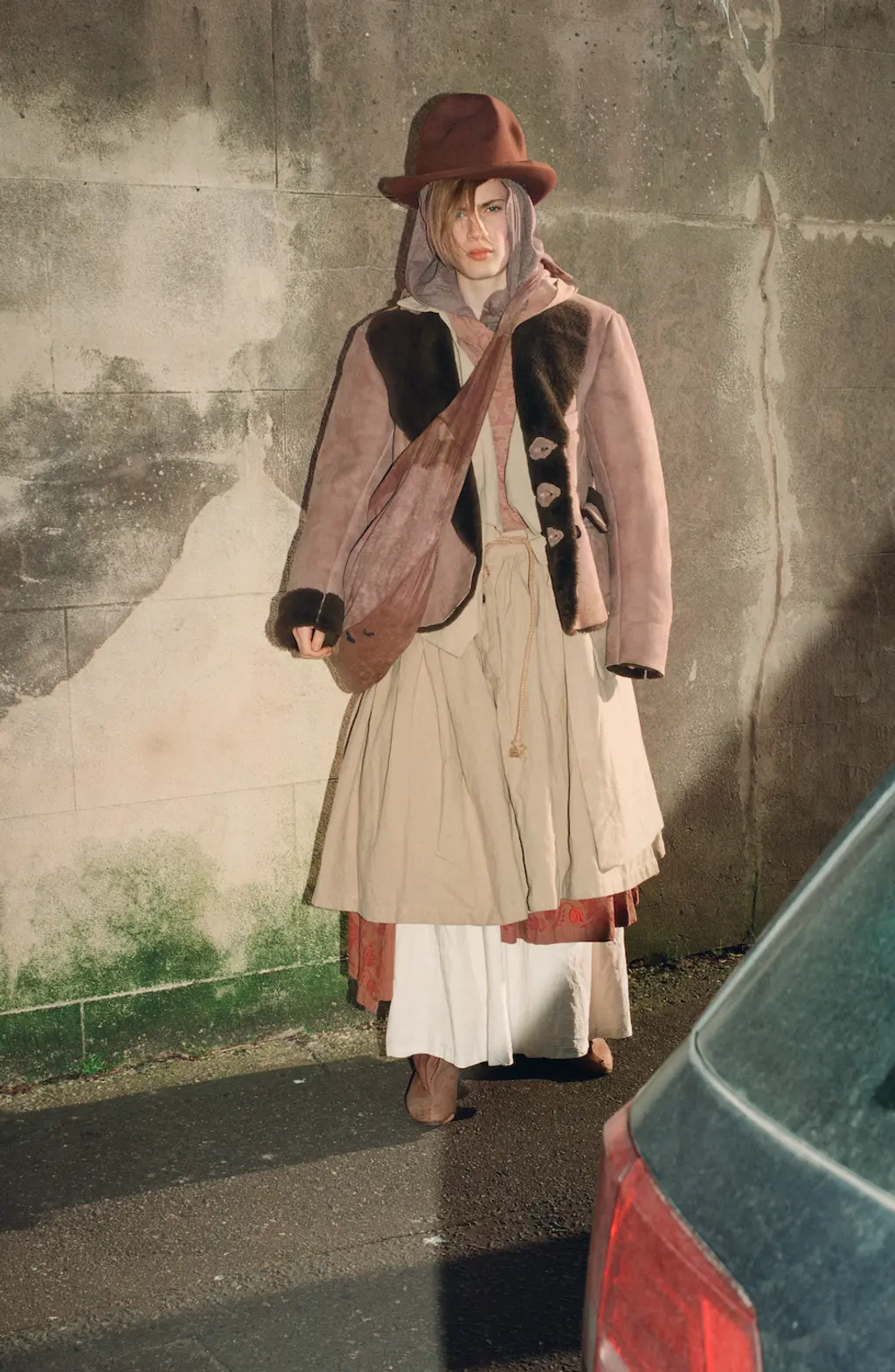

Buffalo/Nostalgia of Mud, AW82

Pirate, AW81

Steven Philip, founder of a former famed West London vintage shop, knows this better than most. One of the world’s largest collectors of Vivienne Westwood, with more than 300 of her pieces, he’s spent a lifetime building up ensembles, paying particular attention to the period just before Westwood began to be taken seriously by the fashion industry. As he explains, “Vivienne didn’t care about what was going on around her, she just cared about what she believed in. Underneath every fucking thing there was creative genius.”

Growing up in Dundee with his grandma (“It was all very camp. Hollywood. Bette Davis. Do you know what I mean?”), Philip was obsessed with fashion, initially from a distance. “You never had the option to go to university or college, or on a gap year. That was for the ‘Timothees’ and the ‘Tabbys’. You went and worked at a factory,” he says. Which is exactly what he did straight out of school.

It wasn’t until later in life, whilst living in London, that Philip was able to pursue his true passion. He started out collecting whatever he could get his hands on and selling clothes at Portobello Market and Kensington’s Hyper Hyper. Educating himself on the best of British designers, he heavily invested in the work of John Galliano, Judy Blame and, of course, Vivienne Westwood. “I spent a month’s wages in World’s End on a sash with four tassels,” he recalls of his first purchase. “You only needed one piece to identify as a fan. I wore it with everything.”

Today, Philip is sitting in his sunlight-filled studio a stone’s throw from the beach in Brighton, dressed simply in a black polo neck surrounded by rare and ornate artefacts piled high on every surface in sight – Westwood, Galliano, McQueen, Comme. It’s a scene that doesn’t sound dissimilar to his formative years.

“I would keep all the clothes in my room. I never had [room for] a bed. I lent punk stuff to Malcolm McLaren for an exhibition and was so proud he had asked me, but it was all piled up in bin liners and I was so embarrassed. He said: ‘Oh my God, this is amazing, this is the way it was meant to be presented.’ These clothes weren’t meant to be kept in tissue paper – they were meant to be lived in. I’ve never forgotten that. That’s why sometimes you’ll see me walking over the clothes.”

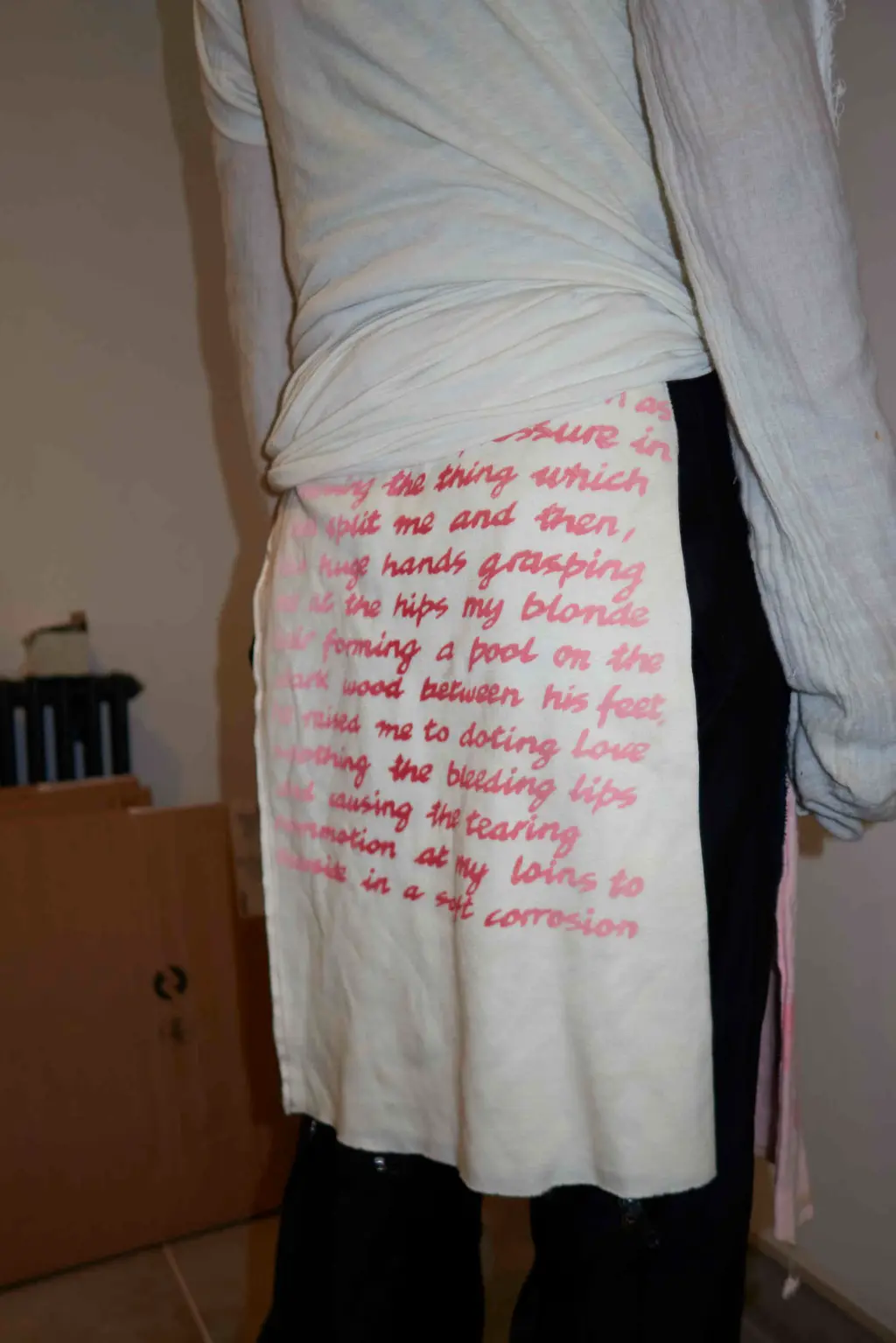

Savage, SS82

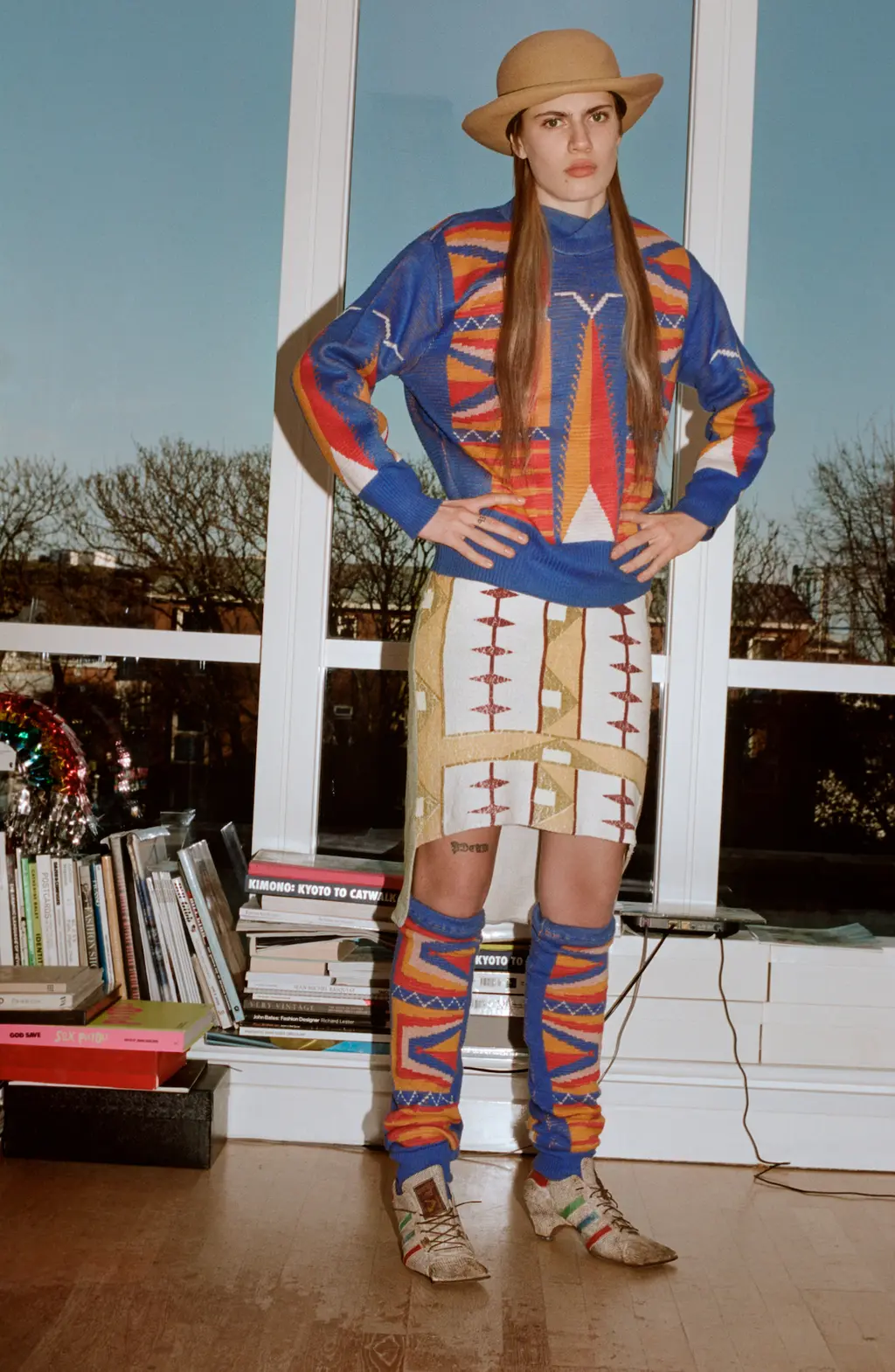

Witches, AW83

Savage, SS82

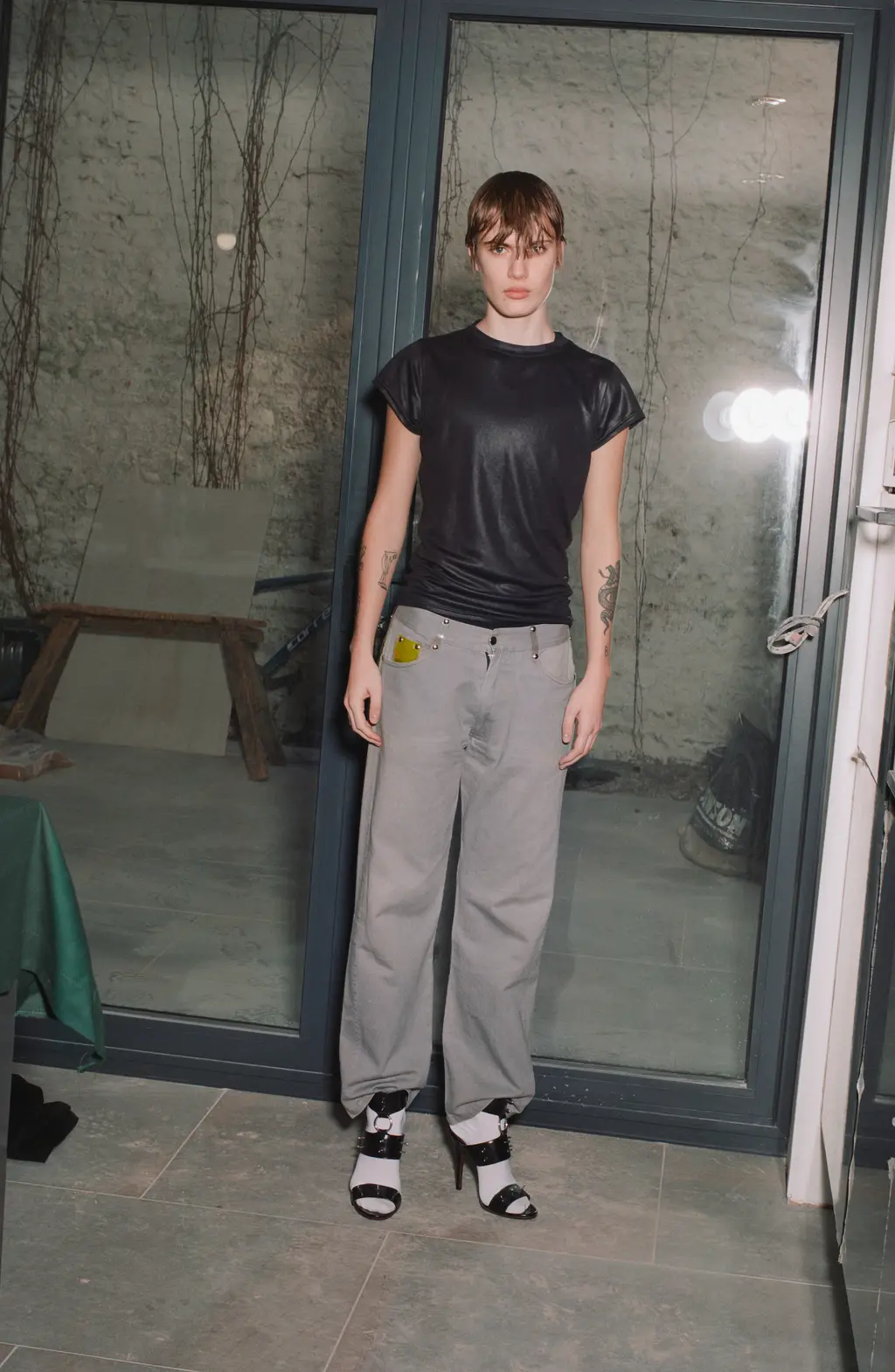

Sex, 1970s

Philip has spent a lifetime building up ensembles. “I sold a full Galliano look to the Met [Museum in New York] for £60,000 three years ago, which financed this studio. People asked me how much it cost and I replied: ‘Ten years of my life.’ I flew to New York once with £2,500 in an envelope to meet someone with a jacket who didn’t know if they were going to sell it. But I left with it.” He recently sold a look from Westwood’s legendary 1981 Pirate show for £24,000. “That’s always been my passion, to put together the missing pieces of a jigsaw. To hunt them down.”

Now, Philip feels safe in the knowledge that he’s completed his own jigsaw. Which is why he’s selling up this spring.

“It’s something I’d always intended on doing, but Vivienne’s passing sealed it for me. She didn’t want to keep speaking about the past. And, well, I’ve done it,” he says, content that he’s completed enough of his own retrospective celebrations. “I’d love kids to press their noses up on the glass at the V&A to see her pieces like I did.” But Philip isn’t retiring completely. Rather he’s going to consult and share his knowledge via youth mentoring programmes. “I want to put these pieces where the masses will see them, not the minority. I’m in negotiations with international museums and I’ll be auctioning some pieces off at two big sales in London, too.”

As one of the world’s largest collectors of Vivienne Westwood, with more than 300 of her pieces, Philip is keen to reminisce about her work before parting ways with it. “Vivienne didn’t care about what was going on around her, she just cared about what she believed in. Underneath every fucking thing there was creative genius,” he says, his lifelong passion still brimming.

“That’s what makes this the greatest story. Vivienne had the movement on her side – the industry had to change, not her. You’ve got to remember that every other designer has had to change. She might have changed over the last 10 years, but she had 15 years where she never bowed down to anyone. It was her way or no way. Not many people can say that they’ve done that.” And for that we thank you, Vivienne.