In Loving Memory of Work: Craig Oldham’s toolkit for resistance

Forty years after the Battle of Orgreave, the creativity of those who took part in the 1984-5 miners’ strike has been carefully documented by the Barnsley designer.

Culture

Words: Jade Wickes

Photography: Craig Oldham

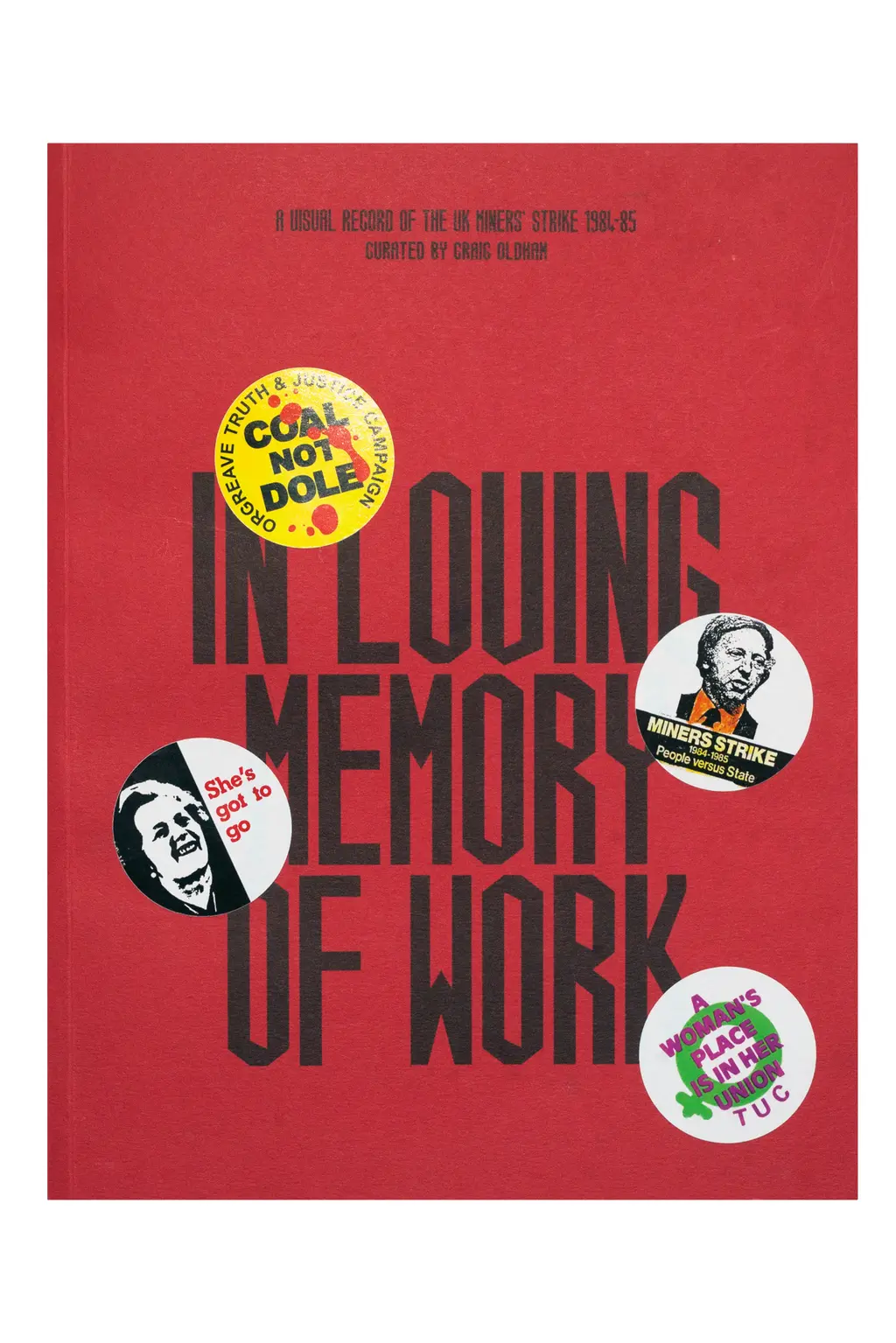

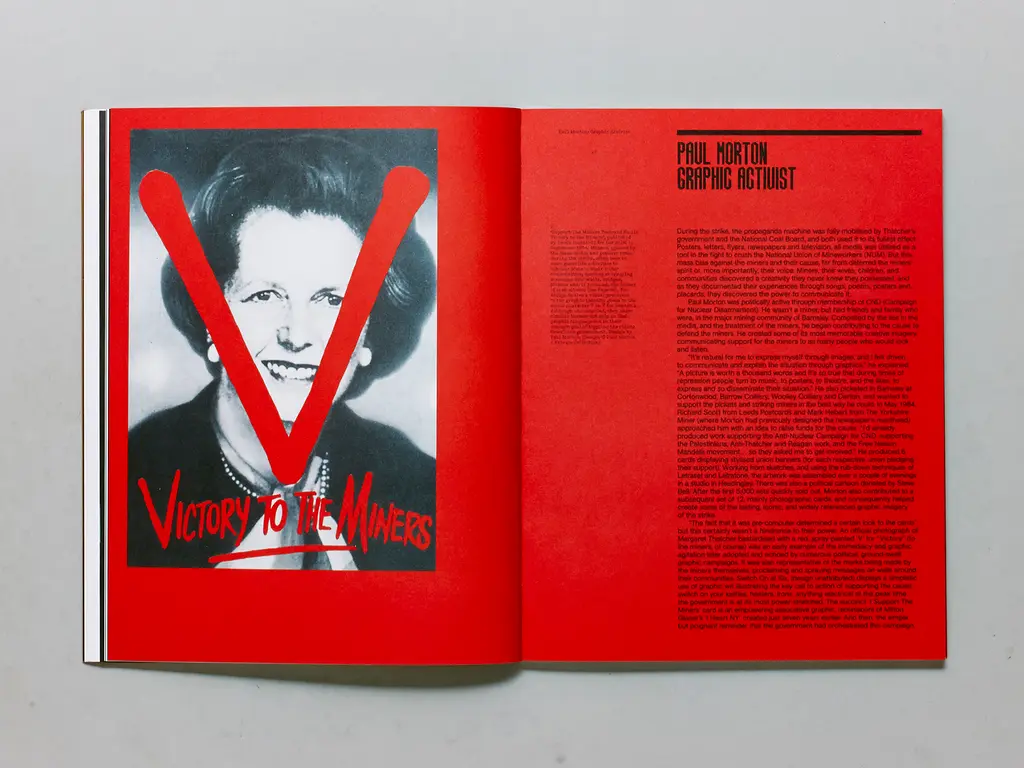

When designer Craig Oldham first published In Loving Memory of Work in 2015, a remarkable book-slash-artefact that memorialises the impact of the 1984 – 5 miners’ strike, he felt, in many ways, alienated by the creative industry.

Born and raised in Barnsley, South Yorkshire – an area affected by Margaret Thatcher’s 1984 announcement of 20 coal pit closures – the 39-year-old was bogged down by the lack of design opportunities back home.

“It was a post-industrial climate where no one had any work,” he says. “We were still feeling the impact of the pits closing down. The town was like an exhaling lung; everyone was leaving Barnsley.”

Following stints working design jobs in London and Manchester, and disillusioned by what he calls “a playground for middle class white lads”, Oldham decided to look inward and backward – at his own personal history with the miners’ strike (his dad was a striking miner), but also the creative ways people express themselves when they’ve got no one to turn to and little-to-no resource. The exact kind of scarcity that miners had to work with.

“I’d taken it for granted that everyone knew about this seminal event that happened in our political history,” Oldham says. “But people had no idea of the resource that was there, all from working class communities expressing themselves and dealing with hardship through making. I thought: this demands a reappraisal. It felt like a duty.”

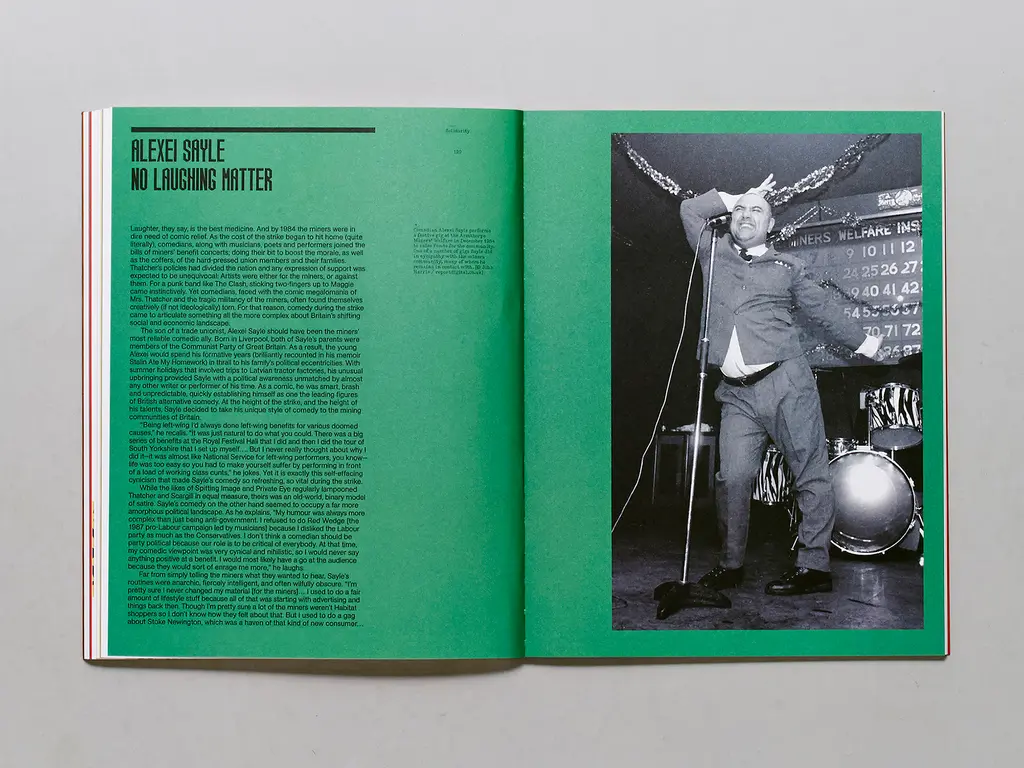

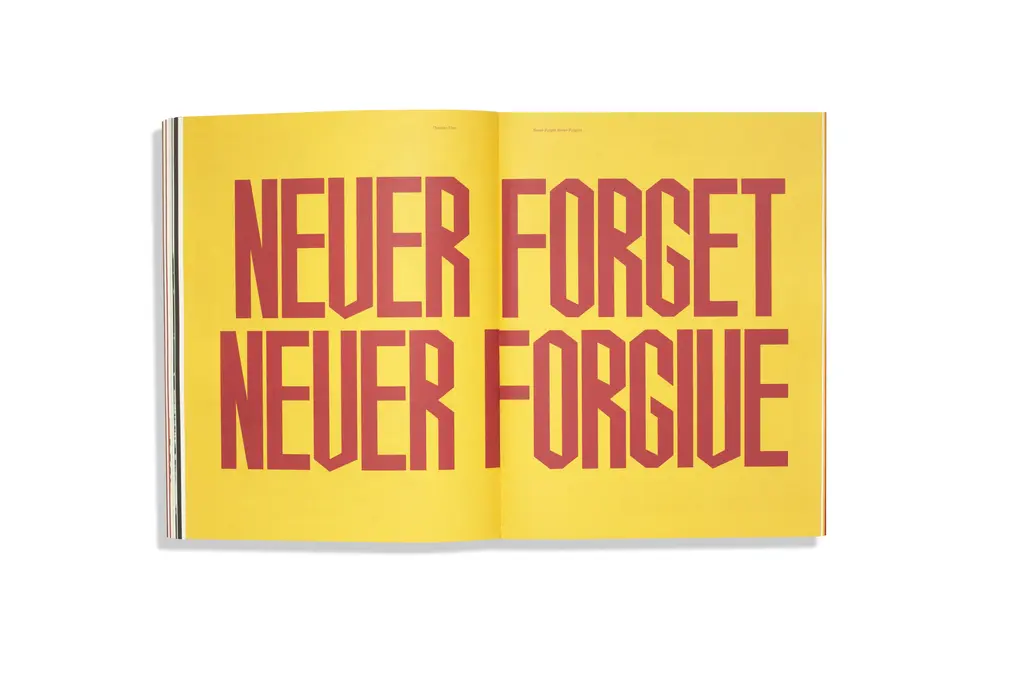

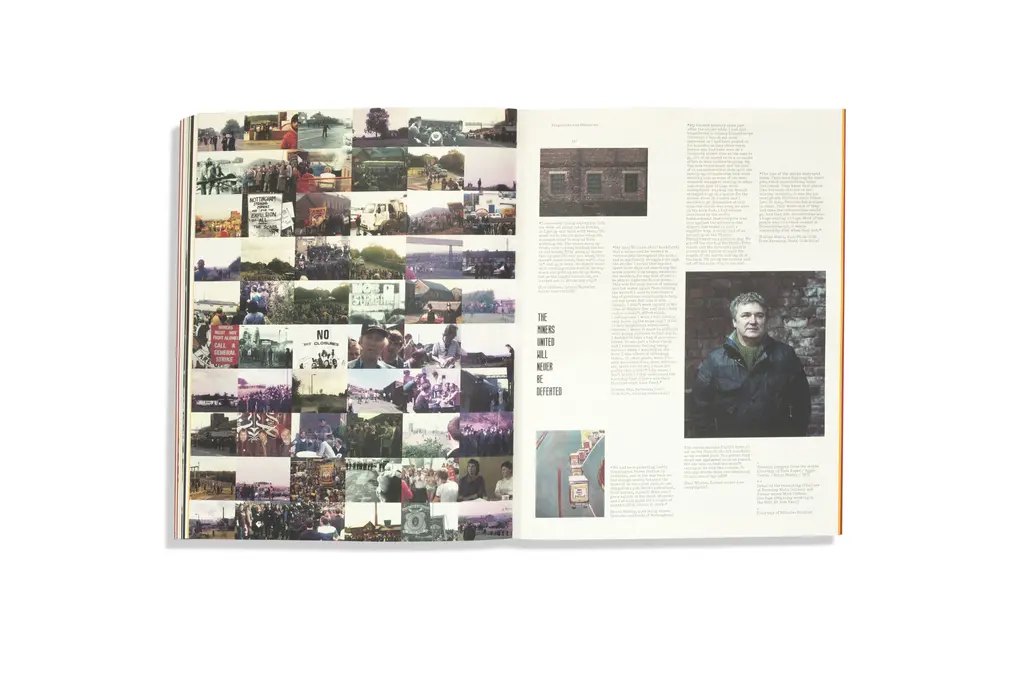

Across 180 pages and featuring a foreword by Ken Loach, In Loving Memory of Work brings together some of the strike’s most distinctive posters and previously unseen photographs taken by striking miner Phil Winnard, while highlighting the simple power of campaign badges such as one that declares “COAL NOT DOLE”, a slogan that was ingeniously engraved onto one pence coins and re-circulated.

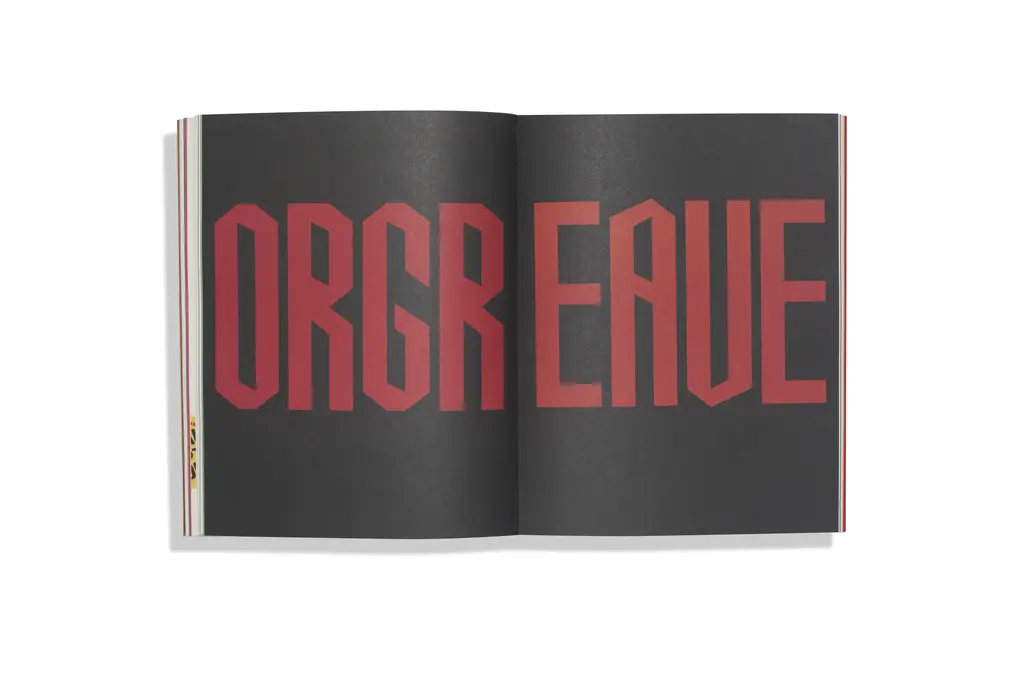

The book is essentially a homage to those who were treated egregiously by an individualist government, whose careless closure of mines caused widespread unemployment and poverty throughout former coalfield areas. Fittingly, today marks 40 years since the Battle of Orgreave, where a confrontation between picketing miners and the police turned into one of the most violent oppressions in British industrial history.

Met with around 8,000 officers who’d been told to “get tough on pickets”, the police carried out previously unseen levels of force onto unarmed and outnumbered miners in the village. It was senseless and state-sponsored violence: brutal arrests were made and little, if any, accountability was taken by the government. Four decades later, Labour has pledged a Battle of Orgreave inquiry, should they win the upcoming general election.

“These people have been willingly, knowingly suppressed and ignored for years,” Oldham says. “I felt like I was in a position to talk about that. I’m proud that In Loving Memory of Work represents people who never had a chance to fully tell their story.”

Hi Craig. Can you talk us through the process of putting In Loving Memory of Work together?

I just wanted to speak to people who made this stuff. The best asset I had in gathering all the material, though, was my dad – he was a former miner who was arrested at Orgreave. It was almost like the Ready Steady Cook method: whatever’s in the carrier bag, let’s make a meal out of it. I didn’t even know it was going to be a book at first, I just wanted to make something compelling about creativity in working class communities. As materials started to amass, it became obvious that a book was the right vehicle for it, but also the people – it was a book for them, about them.

There were gaps in the history to be filled, as well: the main one being Women Against Pit Closures and the women’s movement more generally. So many working men told me they wouldn’t have been out on strike as long as they were, that they wouldn’t have been able to sustain their fight, had it not been for what the women did – not just in a supporting capacity, but in a leading one. They were so powerful.

Families broke up as a result of the strike, which is what happened to mine: my parents got divorced when I was five, around ’89. Largely, that was because my mum didn’t want to slot back into a patriarchal structure [after the strike]. She was like, fuck off – no way. She saw another side, where women didn’t have to fulfil a role that was historically foisted on them. We can learn so much from these women. A large swathe of the community went a full year without any wages. They clothed people, fed people, kids had presents for Christmas. And they did it all with no money! It’s remarkable. It was a privilege to put all of this information together into a book. I almost see it as a toolkit for resistance that’s defined by solidarity, humour and stoicism.

It was originally published in 2015, but you’ve recently released a revised third edition with some new additions, namely the Disobedient Objects section, which highlights ordinary objects that have been reimagined as tools for protesting. Tell us more about that…

The first and second editions were triggered by finding new waves of material. And initially, I couldn’t really photograph things the way I wanted to because I had limited means. The second edition came along because we found a miner-slash-photographer who had rolls and rolls of films that he developed himself, in his cellar, and they were amazing shots.

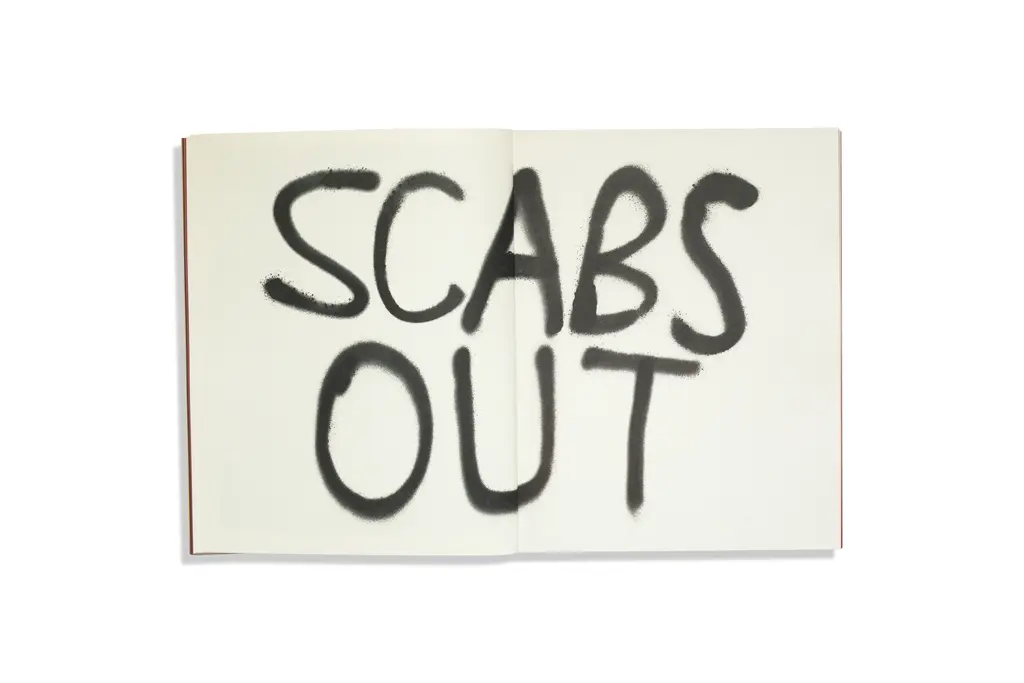

With Disobedient Objects, what I wanted to do was go into the layers of why these things have value – the same way that people might reappraise something like Picasso’s Guernica as a piece of protest. I really wanted to highlight that the miners used everything they had at their disposal to express what they were going through. Every single one of those objects exists in normal life, but they flipped their meaning completely: they etched “scabs out” into coins that they put back into circulation. Who knows whose hands those ended up in? Bed sheets were ripped apart and used as banners. These things gave the book another dimension.

What do you think resistance looks like today?

I think the fact that people are still prepared to get out on the street and do something is amazing. What’s happening in the Middle East, with Palestine, we need to support that. The Palestinian people need our resistance. More holistically, though, there’s a breed of armchair activism that often happens, too: petitions, stuff like that. There’s an itch that people need to scratch when it comes to the guilt they feel, which is often supplanted by chucking their email onto an online form. Fuck all comes of those things. People are more amenable to protest, but not so much to activism. Protest is a singular thing. But activism is something that needs to be sustained. Activism is a set of principles that define your life.

Do you envision In Loving Memory of Work as a rolling project that you keep adding to over the years?

I don’t have an end goal. I like the fact that it mutates and that it’s got so much to say. But there are some pressing concerns that the book has: we’re pushing for a Hillsborough-like, independent inquiry into the policing at Orgreave in June 1984. No police officer at any level has been held accountable or apologised. Until that comes to pass, I want this to remain as a campaigning tool.

And what do you hope people will get out of the book?

People sometimes say to me that coal is a dirty word – what about the environment, the climate crisis? These are valid points, but I’ve never once looked at this book and thought it was about coal. It’s about people. It’s about how people were treated and what a government that is democratically elected shouldn’t be allowed to do to its citizens. It was barbaric, and the consequences were barbaric. These people had incredible skills and knowledge that would’ve been transferable into green energy, but they weren’t given that opportunity. They were told, quite plainly, to fuck off and fend for themselves. It was a Thatcherite, Raeganite, individualist approach.

So I don’t want people to celebrate coal or to think we should send men back underground. But we should respect towns and cities such as Barnsley, Sheffield, Newcastle and Nottingham, which exist because of what is under the ground. I want In Loving Memory of Work to celebrate that; to live as a kind of monument to it.