The book excavating queer cruising culture

Cruising is alive and well, kids. The proof is in this photobook.

Culture

Words: Tiffany Lai

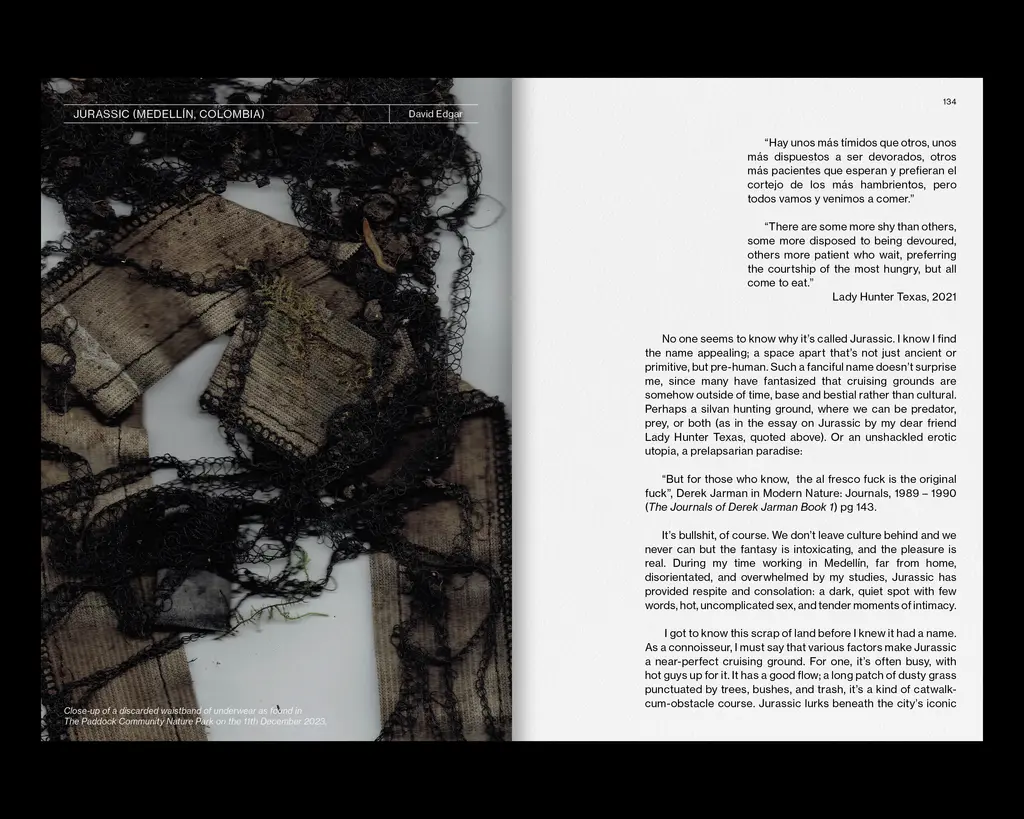

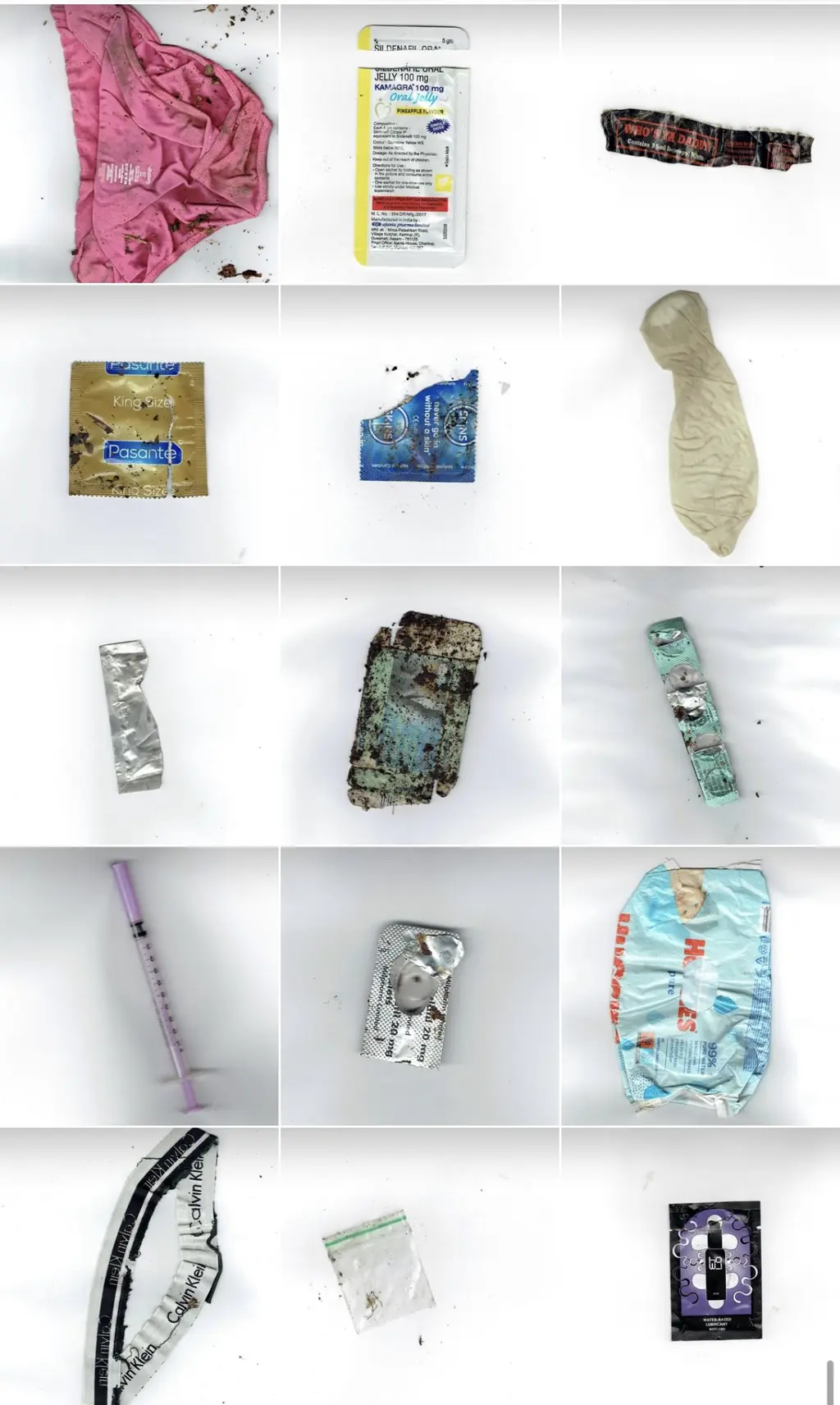

A ripped condom wrapper, a muddy bottle of half-empty lube, a torn-off waistband and a curled, bright yellow popper wrapper. These are just a few of the items that can be found in Cruising Archaeology, the latest book from queer publishing imprint SMUT Press.

Inspired by the Instagram handle of the same name, the book is sprawling documentation of objects and artefacts specific to London’s rich history of gay men searching for sex, particularly in the city’s parks. Meticulously collected and scanned from notorious cruising spots, there are over one hundred items in Cruising Archeology, each one telling a story about an often overlooked aspect of queer life.

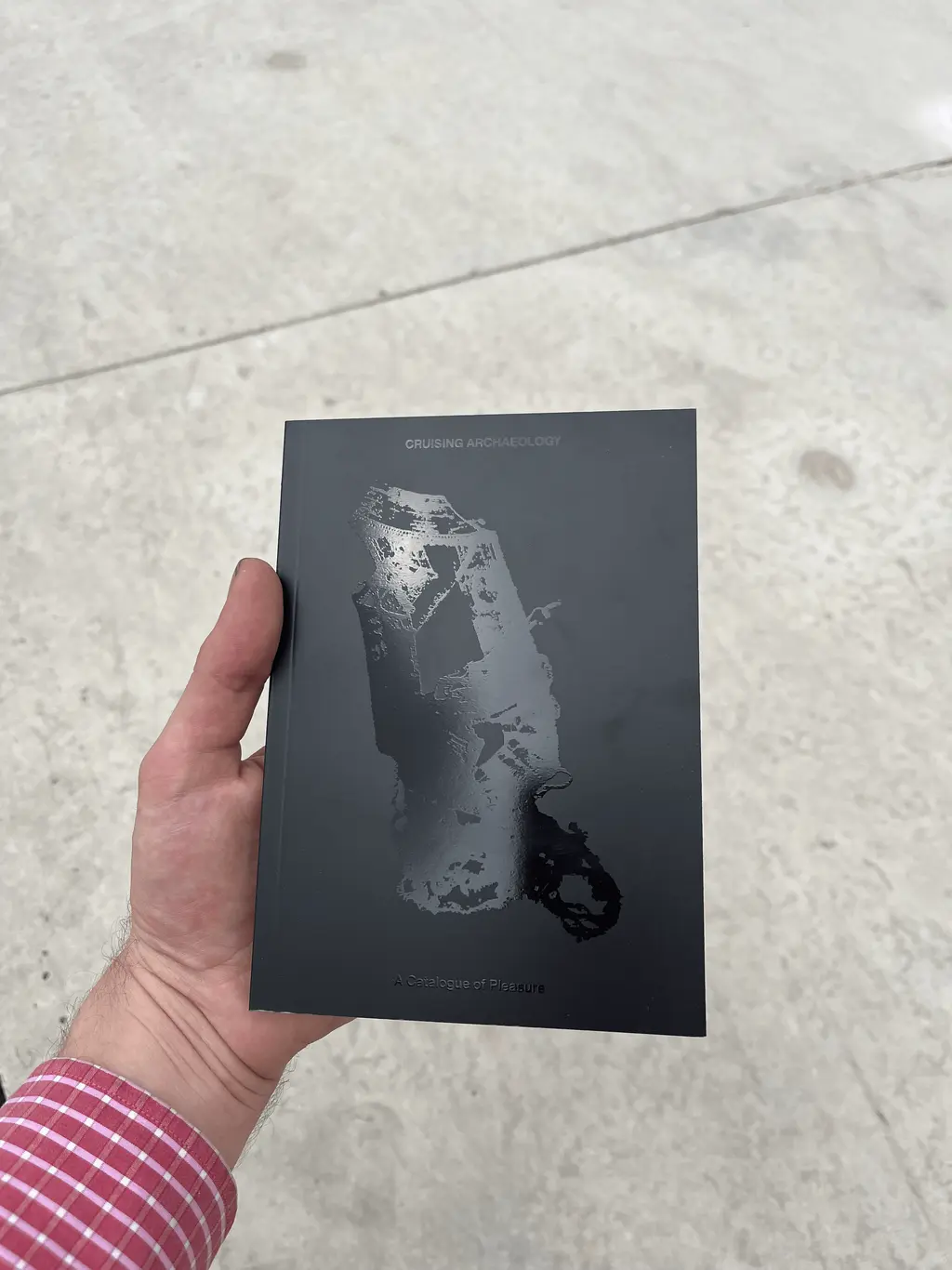

For the cruiser-on-the-go, the photobook is conveniently soft-covered and pocket-sized, with a mysterious matte black cover that alludes to a little black book, “a term that generally refers to a journal containing a list of personal secrets and records”, SMUT tells us. Alongside images of objects that are bursting with sexual history, Cruising Archeology also features a foreword from Marcus McCann, author of the 2023 book Park Cruising: What Happens When We Wander Off Path; an interview with OWL, a volunteer litter-picking group primarily made up of cruisers; and a report on Jurassic, a renowned cruising site in Medellín, Columbia.

We caught up with the mind behind it all at SMUT – who preferred to remain anonymous – to ask all bout the book’s cultural excavation and what they found along the way.

Hi, SMUT. How did the idea for this project come together?

It started last summer, after I was introduced to a cruising area in East London and began to spend a lot of my time there. It was well-known for being a busy sunbathing spot when the weather was right, so people would often spend a lot of time here. At some point I began to notice that they were leaving lots of litter behind; I thought it would be interesting to think of the area through the waste that was left behind. I had seen lots of photographic projects on cruising and they all seemed to fixate on bodies and the moment of contact between those bodies. I think those works can run the risk of being unnecessarily sensationalised, depending on the author and audience’s relationship to cruising. [Cruising Archeology] adopts a more topographical approach.

What makes a good cruising spot?

There are so many factors and each cruising spot that I’ve visited has had its unique characteristics that made it special. A good cruising area needs to balance contradictions: it needs to be both easily visible but also have the possibility to easily slope off and hide away. It must be accessible but not too easily accessible that anyone could stumble across it. Knowledge of it must circulate far enough that there is variation and consistency in footfall, but also not be too well-known that it risks exposing itself to dangerous threats. From my experience, the better cruising spots are the ones where a community has formed through the same people attending frequently. It’s generally an assurance that people feel comfortable and that it is safe to be there.

What can we learn about cruising from these objects?

We can learn a lot about the kinds of pleasure men have in these areas. I came across a few sex toys in these spaces that made me wonder how they had been forgotten about. One of the most compelling objects for me was found in Tottenham: a large thick stick that had a single use face mask wrapped [around] to the end. I can only presume it was a makeshift sex toy, but it looked very painful and seemed so rudimentary that I struggled to imagine it being used in that way. I thought the face mask was interesting because it situated the object within a certain time frame of between 2020 and 2022, during the pandemic.

We can also learn about how pleasure is chemically enhanced in these spaces. The presence of Kamagra jelly, Viagra tablets and popper bottles were some of the most frequent things I came across. But the presence of needles, tourniquets and discarded pipes point to newer and more concerning trends around chemsex.

Why are these items are important to archive?

They preserve a history that very often gets overlooked. Cruising can be dismissed within queer history and politics, because the communities and locations around them can be obfuscated. In the 1980s, at the height of the AIDS crisis, cruising was demonised by those in power as a [signifier] of promiscuity and a major causation behind growing rates of transmission. What is often not considered is the way that many of those cruising were the first to adopt new forms of safer sex, because they recognised the higher risks of exposure they put themselves in. In my home country of Ireland, the murder of Declan Flynn in a cruising area in 1982 was the catalyst for a wider LGBT political movement to enter public consciousness. In 2015, Ireland voted to amend the constitution to allow same-sex couples to marry. It is interesting to think of this direction of progression being borne from cruising.

What do you do with the items after you’ve photographed them?

All the objects have been separated into various boxes based on their date and location of finding, and then placed into a larger box. I have kept all of the objects from the project. The next step is to figure out what to do with them. I had some items to suspend in resin, but once they are sealed it feels quite definite.

What’s the relationship between the Cruising Archeology book versus the Instagram page?

I find the relationship a little complicated, because I’m not sure I have completely worked that out yet. I think, for one, the Instagram page is a lot more expanded in terms of the breadth of objects – printing costs meant that we had to make a lot of decisions about which objects to include and which to cut, and obviously those decisions inform how each space is represented.

The book as a fixed material piece may not have the live interaction or engagement that the Instagram account has, but the format of a printed publication allowed me to explore written pieces to accompany the images. In some ways, the book and Instagram account continue to complement each other and I see both as equal parts in the project.

Why did you make this edition pocket-sized?

We decided to make a slightly smaller book so that people can easily carry it, the idea being that the images in the book would act as some kind of directory or field guide when in a cruising area. The silhouette of the underwear and the text on the book’s cover have been printed with spot UV printing. The text and silhouette are only visible if the book is closely inspected or seen at a particular angle, evoking these characteristics of visibility and obfuscation in cruising. The book’s exterior is inviting because of its mystery and is a direct reference to the little black book euphemism.

What advice would you give to new cruisers?

Be perceptive and respectful. Cruising is a set of cues made up of various body language signals and eye contact. It’s important to try and pick up on these signals to understand if interest is mutual. It can be a tricky environment to navigate and there are plenty of guys that come to cruising areas who may not be out. I would advise new cruisers to treat everyone with respect, because some people who come cruising are in particularly vulnerable situations and just want to find some kind of connection. Kindness goes a long way.

How have dating apps impacted cruising?

I think the relationship between technology and cruising today marks one of the biggest changes and challenges to the practice in the last twenty years. The rise of the hook-up app has transferred cruising from the public space into our bedrooms and also changes how we cruise. Cruising in public spaces encourages us to behave with an openness to those around us. The thrill of the cruise is that it is predicated on a more instant moment of connection that can really disrupt the limited framework of desire that gets imposed on us through technology. Whilst apps such as Grindr or Scruff may make finding a sexual partner easier, they lack an amount of spontaneity that cruising will always offer.

In spite of that, cruising is here to stay?

From what I have seen, in terms of younger generations coming to cruising areas, I don’t think that cruising is going anywhere. I think that spirit of queer transgression and deviancy will never die. I also think that, within this space, it is important to note how apps and sites such as Squirt.org and Sniffies propose a future of cruising in which technology complements and supplements cruising – but, unlike Grindr, keeps us outside!

Testim Transdermal Gel Testosterone 50mg

This is a topical gel derived from testosterone, which helps to maintain normal levels of sexual desire and performance, as well as gaining muscle mass, energy levels and strength. It is also used as a gender affirming medication. For me, this was a really compelling artefact because it raised interesting questions about gender in relation to cruising areas.

Cruising areas exist within a long tradition of primarily gay male subcultures, in which masculinity is often a prized attribute. But the presence of this gel opened up thought for me about how cruising areas could include a wider range of bodies and genders. This was found in Snaresbrook, Waltham Forrest.

Red Ribbon Pasante condom foil

The red ribbon is the universal symbol of awareness and support for people living with HIV. On 1st December every year, red ribbons are worn to show support for people living with and affected by HIV, and to remember those who lost their lives to AIDS.

When AIDs first struck in the 1980s, cruising spaces like bathhouses, porn theatres and tearooms were denounced as sites of transmission and many of these spaces closed. In Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, Samuel R Delany wrote extensively about the redevelopment and closures of many porn theatres through the process of “cleaning up” Times Square during that time. However, gay men adapted to new forms of sexual practices to minimise risk and to keep themselves safe.

Many of these sex institutions became the first sites to adopt and enforce these sexual practices. This is a really significant object that speaks to the historical role and lineage of cruising in relation to the HIV/AIDs epidemic.

Broken Emtricitabine/Tenofovir tablet

This is a fixed-dose combination antiretroviral medication used to treat and prevent HIV/AIDS. It contains the antiretroviral medications emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil, and is more commonly referred to as PrEP.

PrEP is a relatively new form of safer sex practice, having only been available since 2012. It’s widely regarded as an effective form of HIV transmission prevention without requiring the use of condoms. Finding this pill in the Walthamstow Marshes speaks to a new dawn in gay sexual health and helps to better understand the demographics of those using these spaces.

Get your hands on a copy of Cruising Archaeology here.