Why should we care about NFTs?

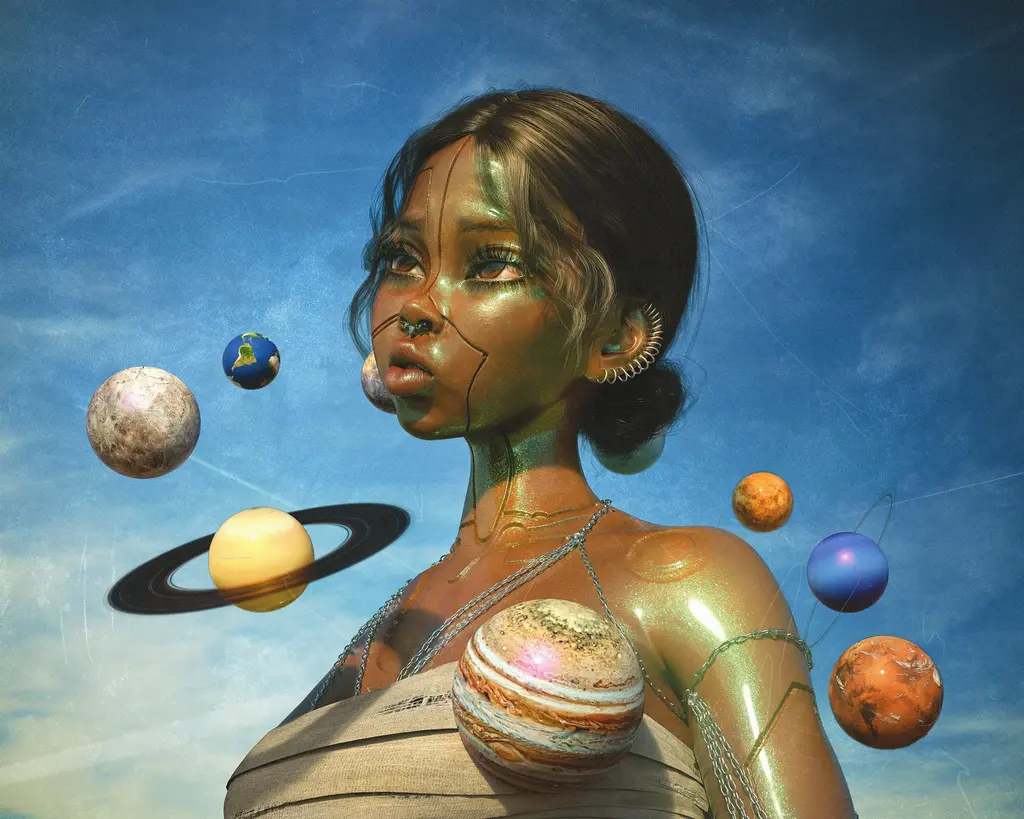

Artwork by Serwah Attafuah (@wrath___)

Deciphering the blockchain boom: explaining Grimes, Beeple and Kings of Leon’s interest in cryptocurrency’s latest gold rush.

Culture

Words: Ashleigh Kane

Last week, a $95,000 Banksy artwork was set on fire by a masked man representing the aptly named Twitter account @burntbanksy. We literally watched money burn on a live broadcast.

Out of its ashes rose the “first-ever Banksy NFT”, which was promptly sold on crypto marketplace OpenSea for 228.69 ETH (or Ether, a cryptocurrency which at the time of sale converts to roughly $380,000). You can watch the replay on YouTube.

The same week, Kings of Leon and Disclosure both announced they would release new music as NFTs, while Grimes sold a “digital artwork” NFT that was “worth” $6 million. Twitter founder Jack Dorsey is even selling his first-ever tweet as an NFT, with a current bid of $2.5 million.

But WTF is an NFT, and why should we care?

“NFT” stands for “non-fungible token”. In its simplest form, it allows people to purchase ownership of a rare digital item that can’t be divided or duplicated. They’re unique, which means one NFT is not equal to another. Anything except money can be minted as an NFT: an artwork, an album, clothing, trading cards, sports highlights, a tweet. NFTs have been making waves since 2017, when a CryptoKitty sold for $114,000 – but why, in the midst of a global pandemic, have they gone viral?

For one, the last year has forced the world into an almost entirely online existence, which includes how we create, view, exhibit, sell, and collect art. Artists have been pushed to rethink traditional streams of income and art-making, and NFT online marketplaces have become increasingly accessible for even the biggest tech novice. They also promise a more decentralised and democratised art world.

Museums and galleries have adapted to exhibiting digital shows, and so too have collectors showcasing acquisitions. Many of these are filled with scarce digital artworks by increasingly known names, like Beeple, and the power equated with owning an artwork now extends to those existing wholly online.

Grimes WarNymph Collection Vol 1 by Grimes x Mac

Grimes WarNymph Collection Vol 1 by Grimes x Mac

Others recognise a viable opportunity to carve out new spaces for artists historically excluded from the traditional art world, such as women, trans and non-binary artists, as well as Black and PoC artists.

Thought leaders like Elon Musk and art world heavyweights such as Christie’s have also stamped their gilded seal of approval on NFTs, immensely boosting credibility, visibility, and curiosity. Recently, Christie’s announced the first-ever auction of an NFT artwork, The First 5,000 Days by Beeple, an artist who has conceptualised concert visuals for Justin Bieber and Ariana Grande. The First 5,000 Days has a current bid of $3.75 million, instantly positioning Beeple in the ranks of highly collectable traditional blue-chip artists (and Banksy).

Where the art market led, the music industry followed. Kings of Leon’s new album When You See Yourself is available for two weeks only and, for $50, fans receive a vinyl and digital download as well as the investment of owning a scarce, limited item. The hope being, of course, that in a few years it’ll be worth considerably more than that.

That’s the dream of many people bowling into the marketplace, speculating whether they can buy, flip, and make a quick buck. Others are in it for the long game, as currently NFTs are not easily turned into cash. This could be due to a lack of buyers, the cost, or a speculative market as the tokens haven’t yet proven they have long-term value.

Traditionally, artists don’t benefit from the secondary market, but NFTs decentralise these sales through a smart contract that guarantees authenticity, provenance, scarcity and royalties for the work’s creator each time the NFT is sold. These smart contracts stipulate the T&Cs between a buyer and a seller. All these details are programmed into an NFT’s code (meaning they can’t be altered) and stored on the blockchain for transparency – which removes the need for a third-party when buying and selling, and thereby awards the creator or re-seller more agency than trading through a gallery, dealer, or auction house. It is direct to market, with the added security of operating through a decentralised system such as the blockchain.

JAH REYNOLDS, ARTIST

The explosion of online marketplace websites minting and selling NFTs cater to a wide range of creators and collectors. OpenSea is effectively the eBay of NFT marketplaces, trading everything from domain names to collectables; Zora is invite-only and curated by an in-house team; and Mintbase claims to be “as decentralised as it gets”, allowing anyone to create and sell. Each NFT minted on Mintbase is also stored on Arweave, “a global, permanent hard drive”, meaning even if Mintbase disappears, the NFT lives on for as long as the blockchain does, offering peace of mind in an unpredictable new era.

The Mintbase marketplace also allows creators to mint NFTs under smart contracts to guarantee that they – rather than the minting platform – own the NFT.

“The future is here,” says Mintbase COO Carolin Wend. “For too long, creators and artists have been exploited by greedy marketplaces and dominant players. NFTs change everything since the art pieces can be traded on any platform and any blockchain wallet. Artists can truly monetise their own creations.”

Serwah Attafuah, a 23-year-old 3D artist and musician from Sydney, is one of those artists. She became involved with NFTs last November, after NFT marketplace Foundation.app invited her to be a part of its inaugural auction. For Attafuah, NFTs encourage her to focus on her art practice and, she hopes, offer a way out from the grind of making art for other people.

Artwork by Serwah Attafuah

Artwork by Serwah Attafuah

“The idea that I could make a living solely off art I want to make, rather than having to adjust to a client’s criteria, is extremely promising,” she says. That said, she adds, it’s up to the artists and collectors to ensure NFTs can push beyond just hype. “Invest in the art and artists that you love, and surely we can make this work for a long time.”

Earlier this year, Jah Reynolds, a 32-year-old Brooklyn-based filmmaker and visual artist, sold his first NFT on day one on the marketplace. He’s seen consistent sales since. Many of his collectors are fellow artists, all mutually supporting, encouraging and appreciating each other in this new space. Reynolds hopes NFTs will offer empowerment and sustenance, with an emphasis on BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ artists.

“I see a community being birthed at a very crucial time,” he says, “and there’s still work being done to make platforms open and expansive.”

Most of this is being done on a ground level by the community itself, Reynolds explains. One/Off, for example, is a platform providing education to Black artists curious about NFTs, and Mint Fund allows creators to pay it forward so that new artists can enter and create in the space.

“I believe NFTs have the potential to be the future,” Reynolds adds. “If we uphold the value of community, continue to address the inconsistencies and create space for all artists, there’s no stopping this.”

If this all sounds too good to be true, it’s because it could be. Someone always has to foot the bill, and if it’s no longer the artists, then who will? In the case of NFTs, Mother Nature. Last December, artist Memo Atken reported that just one NFT is accountable for a staggering 211kg of CO2 emissions, equal to driving a car for over 600 miles. Those emissions are the byproduct of Ethereum mining, says Damien Schuster, Advisor of Growth & Partnerships at Offsetra, the carbon offset company that prototyped carbon.fyi, a methodology and calculator that breaks down the energy use for an Ethereum user.

DAMIEN SCHUSTER, ADVISOR OF GROWTH & PARTNERSHIPS AT OFFSETRA

The blockchain is a decentralised ledger made up of “blocks” containing all the transactions made on it. Currently, it operates on a “Proof of Work” (“PoW”) system meaning participants, or “miners”, compete with others to key in complex computer calculations that create (“mine”) new blocks, secure the blockchain network and ensure no one is misbehaving (spending their money more than once, for example.)

Because of the nature of this process, miners operate high-powered computers which suck up eye-watering amounts of energy. As Schuster explains: “There’s a lot of graphic cards, and hence a lot of rare-earth metals and such.” It’s a highly competitive space and many miners can work on the same block simultaneously, but the miner who solves the problem gets rewarded in cryptocurrency.

Offsetra aims to counteract Ethereum mining’s footprint by sourcing high-impact carbon offsetting projects that provide tangible social and environmental benefits, like rainforest protection and renewable energy installations.

“As crypto-enthusiasts, we were dismayed at the massive energy consumption of the collective network,” says Schuster. “NFTs present an incredible opportunity for awareness and education around environmental issues [and] art is an important medium of exchange.”

Artwork by Jah Reynolds

Artwork by Jah Reynolds

Schuster notes that some platforms, like Zora, are already taking steps to minimise the damage of NFTs. But ultimately, he says, the responsibility must fall on the minters and be factored into the minting’s gas prices. This is the fee someone pays to mint an NFT, and to have new blocks created on the blockchain by miners for it to live. The higher the demand for minting, the larger the gas fee is.

Offsetra’s methodology and calculators assign those mining emissions to the NFT minter, Schuster says, “because they benefit from the network, they congest the network (increase gas fees), and ultimately drive demand for Ethereum – which is what miners are seeking.”

Schuster encourages NFT creators to reach out directly to Offsetra, in order to better understand how to minimise their impact and tune into Twitter, where the discussion is urgent and ongoing.

As Attafuah and Reynolds suggest, whether NFTs are a fad or the future will ultimately be up to the artists and collectors cultivating an already volatile landscape.

There is a great opportunity to forge radically decentralised systems that allow not just a handful of players to profit, and could open the door onto a more democratic and accessible world. The utopia where artists are free to create and earn their worth feels closer than it’s ever been. But for it to be truly equal, it must be sustainable for all – including the planet on which we create.