Fantasy Island shows Ireland as it really is

In compiling the work of 70 Irish photographers from 1975 to the present day, Belfast-based creatives Lucy Jackson and Joel Seawright shine a light on Irish culture beyond the Troubles.

Culture

Words: Tiffany Lai

For many young photographers in Ireland, stepping out from the shadow of the Troubles can be a challenge. But for the generation born after the mid-’90s peace process, there was always much more to life than checkpoints, arson and barricades.

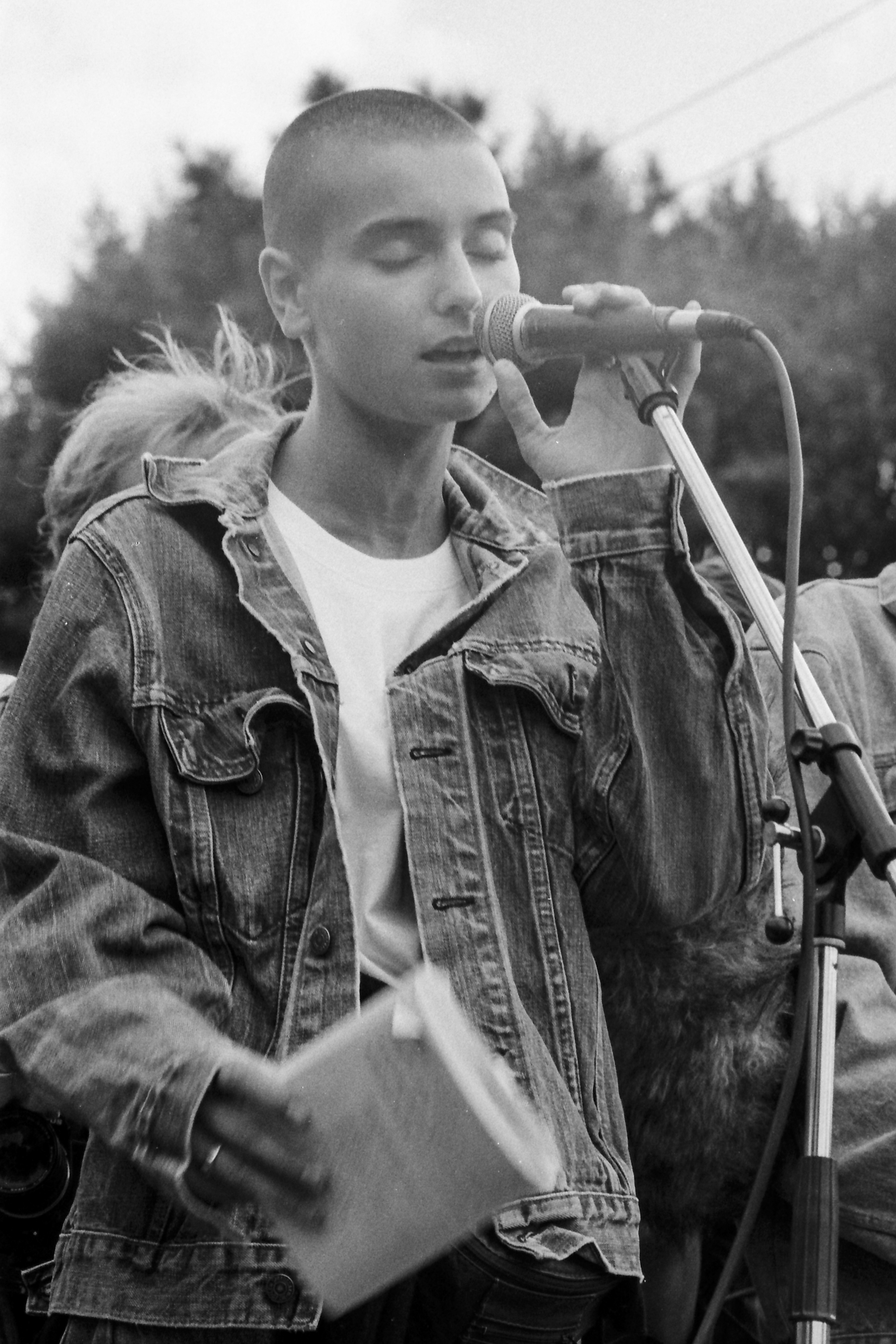

In an effort to capture more of the vibrancy and breadth of Ireland’s contemporary landscape, Irish graphic designer Joel Seawright and Kent-born curator Lucy Jackson have put together Fantasy Island, a photobook featuring 157 images from 70 Irish photographers. In presenting images from the north and south, from the two decades either side of the 1998 Good Friday agreement, visual relics of the conflict are unavoidably present. But for the younger photographers presented there was a different focus in their work.

“The violence experienced by my parents’ generation made documenting what was happening feel essential – a way to survive, process and make sense of their surroundings,” says Joel, 27, who now lives with Lucy, 25, in Belfast. “Up until the early 2000’s, it was rare to find an artist who wasn’t engaging with the aftermath of the conflict in some form.”

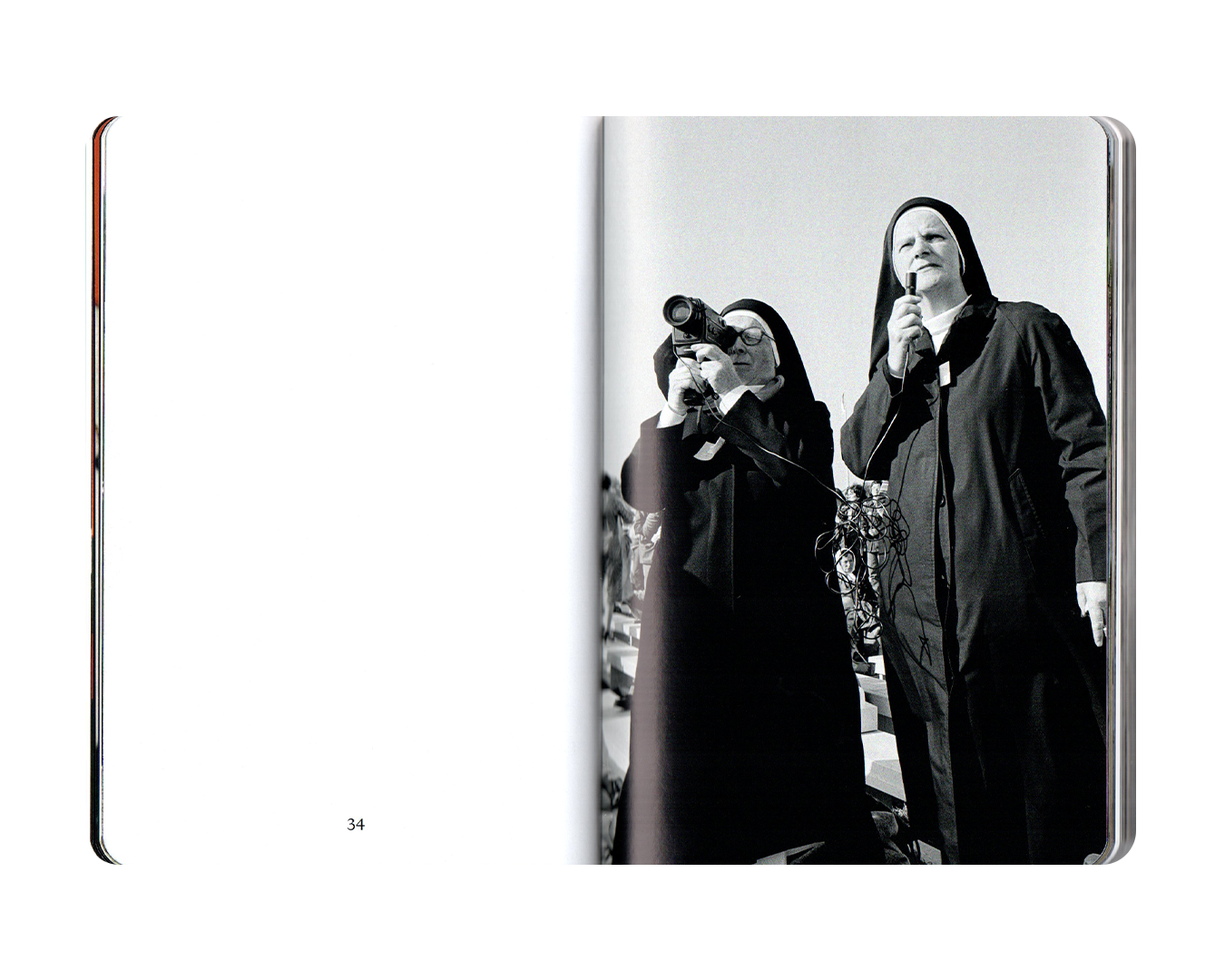

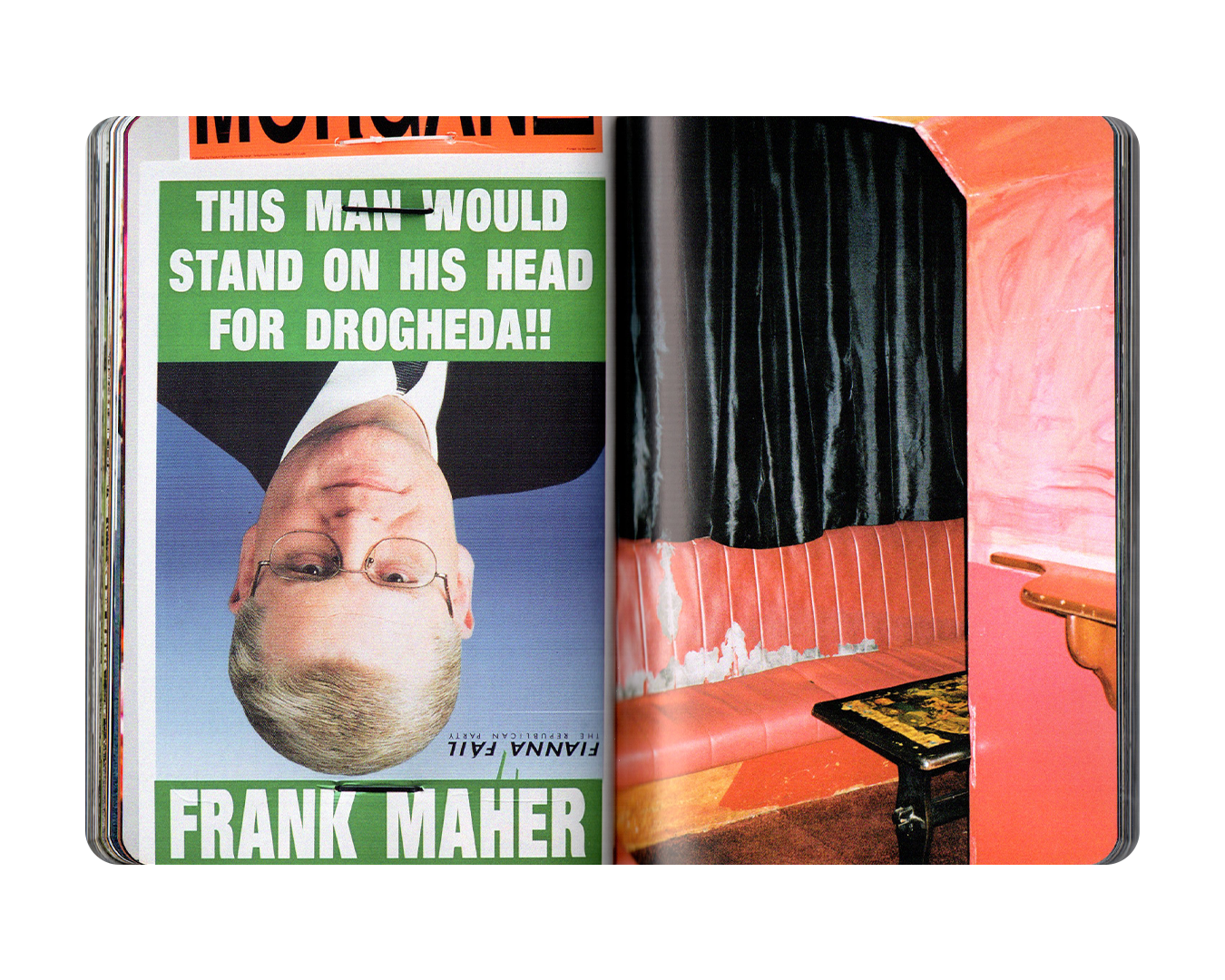

The book’s pages feature no titles, dates or credits. Those are consigned to the index at the back, although still without explanatory captions. Instead, Fantasy Island purposefully evokes a sense of an infinite now through a contextless stream of photos. They leave the viewer with more questions than answers. When was this image taken? Why are those dogs muzzled? Why is this man at what looks like a house party wearing a balaclava? How long has that burnt car been sitting there? And why are these images of a dead fox and ’70s punks next to each other?

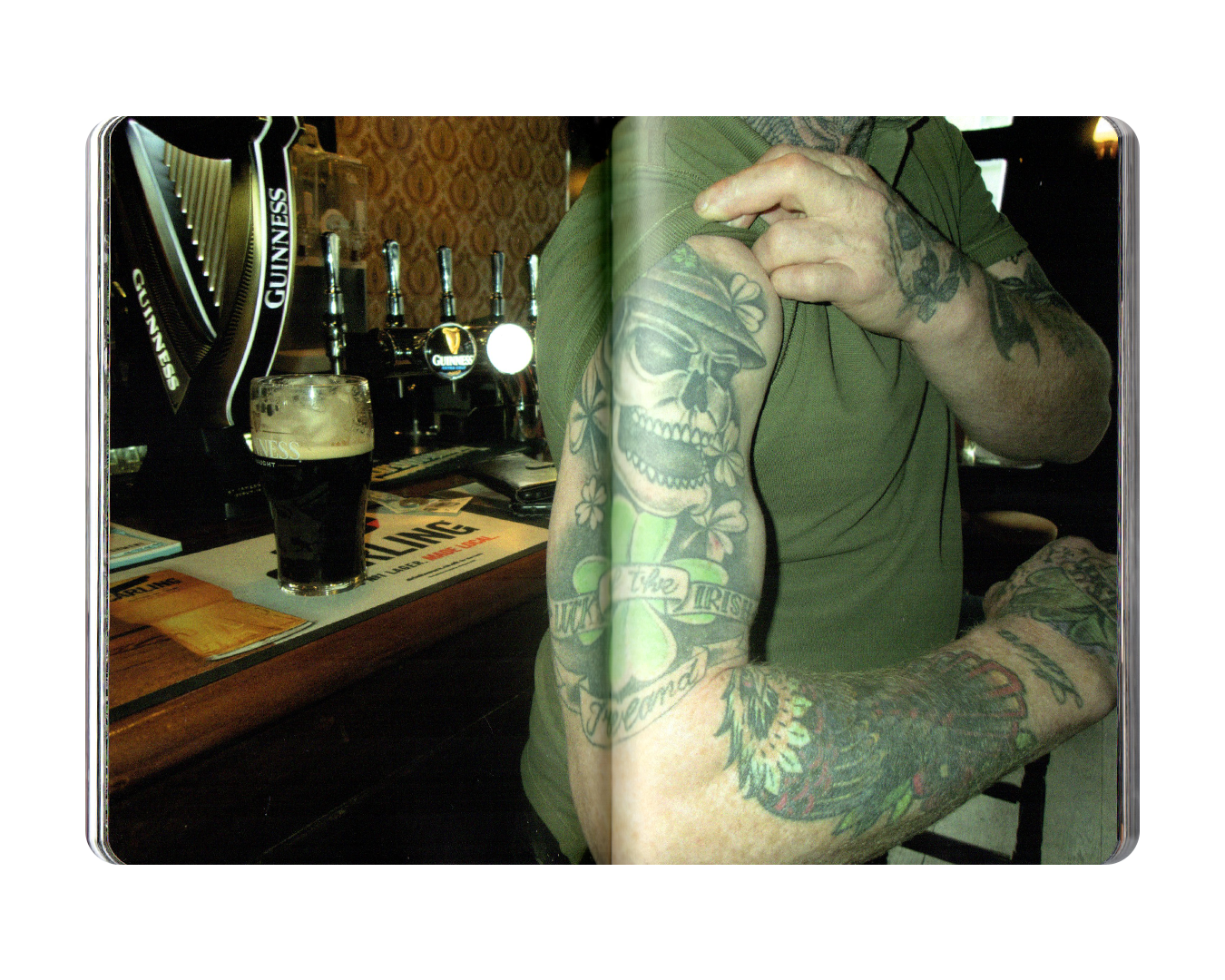

Eschewing the idea of a grand narrative of 50 years of modern Irish history, the images and their layout speak to what Joel refers to as the book’s “mythological tone”. Slice-of-life imagery (ravers, nuns, pubs) rubs up against ghosts of the recent past (protests, murals, bullet holes).

Take Eimear Lynch’s photo from 2024. Captured at a teen disco in Cork, four 14-year-old girls are standing by a mirror, all clutching iPhones and wearing bodycon minidresses. One of them holds her phone aloft, capturing either Eimear or the party behind her. On the next page is a black and white reportage shot of women protesting, sometime in the ’80s, holding a large banner reading “Women against Armagh strip-searching”. Fantasy Island is then and now, political and personal, historic and quotidian, the Troubles and the untroubled.

Joel and Lucy are especially proud of one spread. On page 186, an image of a group of Ulster Defence Association members in insignia’d jackets and sunglasses is positioned next to a photo of women in church, all holding babies dressed sweetly in pink, in line to be christened. The images look eerily similar, both groups standing in the same formation.

“We’re exploring who we are beyond the conflict,” Joel says, “while still holding space for the past and recognising how deeply it continues to inform the present.”

Hi guys. You’ve worked together on several projects, including punk-inspired photography magazine Rotten Magazine and Rotten books. But how did you meet?

Lucy: We met in 2017 when we both moved to London to take part in a programme to get people that hadn’t been to university into creative jobs. It was only meant to be for three months but we both ended up staying for seven years.

Joel and I clicked straight away and, soon after meeting, moved in together and started Rotten Magazine. We’ve been creating things together ever since.

Why did you decide to make Fantasy Island?

L: Creating something like Fantasy Island was actually an idea I mentioned to Joel when we first met. Coming from England, you don’t really learn about the Troubles in school. When Joel started telling me about [the history] and the culture scene in Ireland, and how [all the creatives] tend to move to London, I suggested that he should make something about Ireland since he felt so passionate about being Irish and Irish culture.

It’s obviously hard to escape the cultural shadow of the Troubles when putting together a book like this. How did you navigate the political aspect when deciding which images to include, and how to display them?

Joel: I didn’t want it to be political at all, because everything you tend to see that comes from the north of Ireland is about the Troubles, in some way. I didn’t want to do that because it was a bit cliché. But just through the nature and the context of the country, stuff started to seep through. It’s inevitable that you have to talk about those things, and they are featured in some way. So it’s about acknowledging the history of the country whilst also seeing how we can move forward and explore identity in a different way, [one] that isn’t framed by the Troubles.

Where does the title come from?

J: We always have music playing while we work on a project, and most of the titles we use end up coming from lyrics that stick with us. When we were working on the book, we were listening to a lot of Elliott Smith and his song Strung Out Again came on. There’s a line where he sings: “Standing, smiling /On some fantasy island /Looking at my lost reflection again.”

It felt like it encapsulated everything we were trying to say and express about Ireland: disconnection, yearning and the uneasy blur between reality and illusion.

The foreword is written by Adam Doyle better known as the artist Spice Bag. Why him?

J: He’s one of the defining voices that has emerged from our generation. His work is deeply rooted in the social and political fabric of Ireland, so asking him to write the foreword felt like a no-brainer. We felt that with his grasp on the current state of the island, he would be the perfect person to provide context to someone picking up the book who isn’t from here. He did an incredible job of distilling everything we had envisioned for the book into the foreword, capturing the book’s themes, energy and mythological tone.

The book covers 50 years of work. Did you see any photographic trends emerge throughout the years?

L: As we started editing the book, certain patterns began to stand out. Some visual motifs kept showing up: police, dogs, murals, bonfires, tracksuits, burnt-out cars. We hadn’t fully realised just how many shared themes there were until we saw all the images side-by-side.

Why did you decide to begin in 1975?

J: The opening image of the Republican woman in a balaclava is very emblematic of the Troubles, and that was taken in 1975. We thought it was a good starting point to acknowledge the past. Then the book moves forward from there. The image is there to dupe the reader out at the beginning. You think it’s going one way, then it goes another.

What do you find exciting about the emerging photography scene in Ireland?

J: There’s something really meaningful about the way this generation is starting to define Irish identity and culture on its own terms. It feels like a pivotal moment – a chance to reclaim and reshape what it means to be Irish today.

Fantasy Island launches on the 5th June at 6pm at The Library Project, Dublin