A rare interview with graffiti misfit Fatzoo

Photo by Will Robson-Scott

Ahead of his new exhibition at the Sunday Painter Gallery in South London, we caught up with the man behind the tag.

Culture

Words: Joe Bobowicz

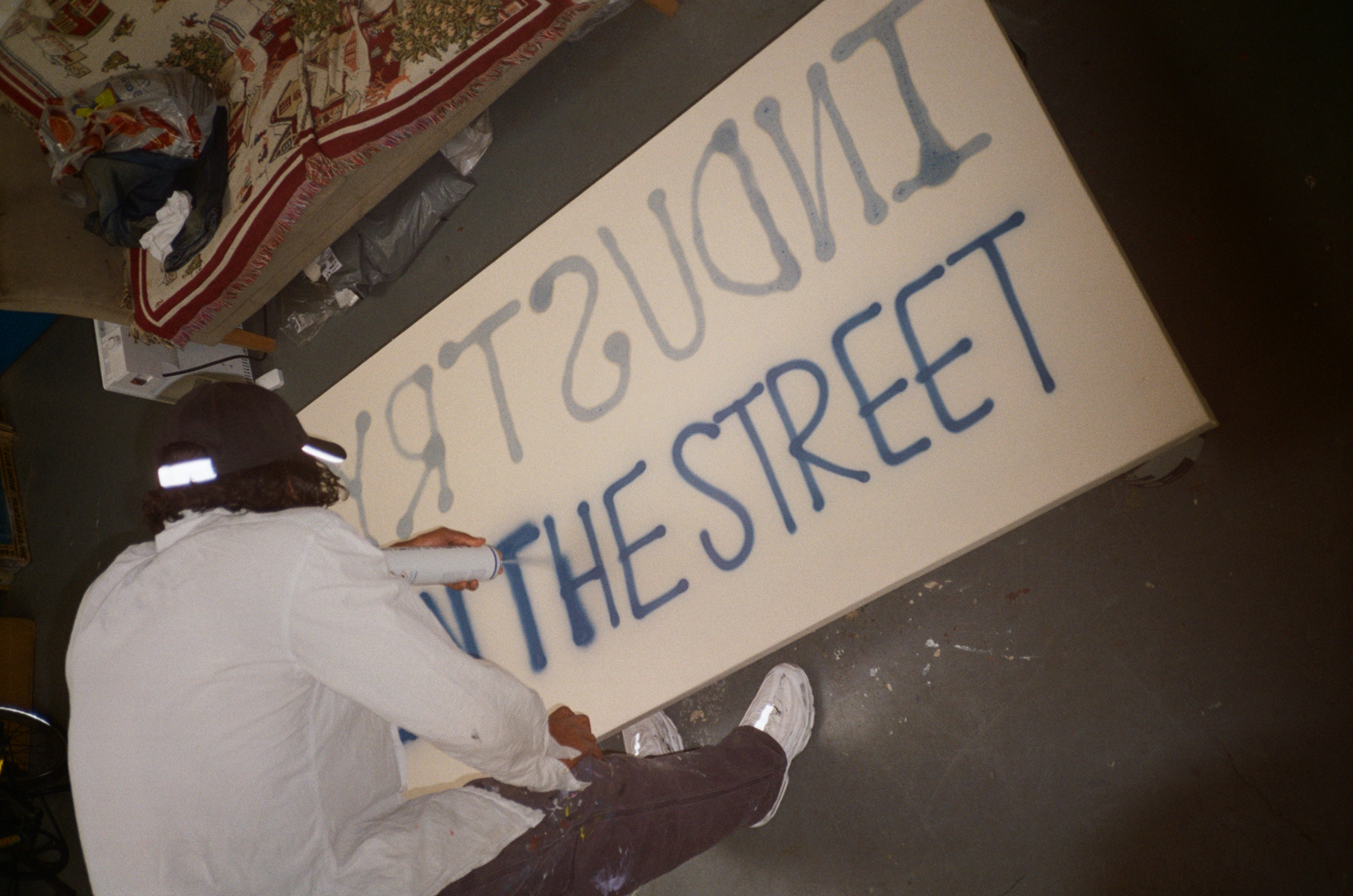

For almost two decades, Fatzoo’s name has been everywhere it shouldn’t: shop shutters, box trucks, cars, trains, trackside walls, you name it. From his native London to New York via Berlin, the graffiti writer is a legend of the medium, renowned for his characteristically rotund dubs (graffiti speak for black and chrome pieces) and throw-ups (simpler bubble designs, executed at speed). “I probably started mid-teens, 15,16, and it was for pure fun,” he says.

However, his lore extends beyond the tight circle of graffiti. Over the last few years, Fatzoo has become a proper presence in the art world, showing complex installation work, drawings and collages in galleries across Europe. Often, his work references clandestine activities that hide in plain sight, as well as drill subculture and incarceration. Previously, under another alias, the artist presented a solo exhibition comprising everyday household items used in drug dealing – foil, cling film, vaseline, lotto tickets – and a collection of miniature number plates from unmarked cars. (To protect his identity, we won’t divulge any further details).

Elsewhere, Fatzoo has collaborated with brands including Supreme and Martine Rose. He’s also produced sell-out T‑shirts with indie label Fungibles, sold via Supreme’s London store, all while holding down his practice.

Photo by Henry Rich

Photo by Ollie Hammick

Like any active graffiti writer, Fatzoo is a walking mystery known only by his tag. His artwork – as opposed to his illegal graffiti – is perhaps where he reveals most of himself. His new solo exhibition at the Sunday Painter gallery in Lambeth, organised with creative studio Burbia, is aptly entitled No one @ me. The works are inspired by Fatzoo’s own experiences as a Black, working class Londoner; interactions with law enforcement and the well-to-do circles the art world has given him access to.

In one artwork, Post-It notes are pinned to a board, each one sharing a pithy observation he’s scrawled down or a poetic one-liner. In another, a piece of astro turf is hung from the wall, sprayed with the words “Informal clothing designed for comfort,” alluding to the duality of sportswear as both working-class leisure dress and purpose-built athletic clothing. Below, his musing continues: “Ghetto until proven fashionable”.

No one @ me – which includes painting, sculpture, drawing and photography – sees Fatzoo articulate his unique vantage point at the intersection of outsider vandalism and the bourgeois art scene. As he puts it, “One foot in the streets, the other in the milky way.” Much of this follows on from works shared on burner social media accounts. Through his art, Fatzoo built a language using found objects, road markings and coded words. Here, in an exclusive pre-show interview with the cult hero, we scratch a little deeper into his journey as an artist.

Photo by Will Robson-Scott

Photo by Ollie Hammick

Hi, Fatzoo! Firstly, where did this alias come from?

A friend called me it, making fun of me [for] being able to finish big plates of food.

So much of your work toys with the aesthetic nuances of class and race through words as well as symbolic iconography. With this in mind, did you feel conflicted entering the art world given its large, white upper-middle class population?

There’s always a conflicting feeling being a working class Black person stepping into that world – it’s inevitable. During my time in this strange world of white walls, long words, champagne, white and upper-middle class people, I make sure to bring through the right people that wouldn’t get the chance to be in these spaces. Slowly but surely we can start to reap the benefits of change on this off-key planet.

As an artist, you’re very carefully straddling different worlds. When did you start thinking you wanted to be a capital‑A artist as well as a graffiti writer?

I never set out to be an artist when I was a kid. There were no artist parents amongst the working class community in the ends, so it wasn’t necessarily something anyone thought could be a career choice. I just always enjoyed getting some paper and pens out, so my mum and stepdad encouraged it.

The graffiti choice was a bit different. My stepdad had old-school graffiti writer mates and was fully around the outside culture that came with it back then, so I was involved before I knew I was involved. This was fully encouraged, mainly on paper, until I was old enough to start noticing it out and about. Curiosity saved my life essentially – [it] could have easily [gone] another route.

When did you first find yourself dissecting the cultural and social cues around you?

From the jump, broski. Growing up with a mix of people, you soon realise – like going to school – that other people may have a lot more or a lot less than you. This was apparent through clothes, so a fresh trackie and kicks were a quick fix to not feeling poor. [For] GCSEs at secondary school, I obviously picked art as one of mine because it was the only thing I liked, and from then I was in class with predominantly white, middle-class kids. That’s when the real dissection came about.

Photo by Ollie Hammick

You often write text in notebooks, Post-Its and on ephemera such as lottery tickets and bank notes as a way of analysing the worlds you move between. What drew you to these mediums?

Making notes is important to me – it helps me remember shit, otherwise I can lose an idea or thought forever. From that, notebooks, scrap paper, post notes and [whatever] else is easily accessible would slowly become my go-to mediums to write on.

Where you’re from in London, the working and upper-middle class come into direct contact in a way that’s rarer in regional towns. What do you make of that?

I didn’t appreciate it growing up. I thought we got the short straw in comparison to some of the middle-class kids, but then again they probably feel the same about the upper-class kids. It’s a blessing, I can’t lie. Even though at times it might feel unfair or annoying, it’s always a treat to learn, a privilege to gain, so if that means I [get] a better understanding of how the other half live, then I’m cool with it. London’s a mad place.

Graffiti often gives us a flavour of who the artist is, but so much is left unanswered with you. What subjects or elements of yourself do you want to share in this show that might not translate through illegal graffiti?

I ain’t giving you too much. Just come see the thing, innit, and you’ll get a better understanding of how I’m thinking.

You heard the man. No one @ me opens at the Sunday Painter gallery on 5th June at 6.30pm until 28th June