How Hulme inspired three generations of photographers

Photography by Hulmeloonies AKA Anni Kay

The mythical Manchester suburb was the epicentre of Madchester. But the nation's best documentary photographers had been intrigued by the inner city area long before Factory Records. Today, Hulmeloonies is carrying on their legacy.

Culture

Words: Davey Brett

Even if you’ve never been to Hulme, you’ve seen it. Kevin Cummins made sure of that on a snowy January day in 1979 when he shot Joy Division on the bridge over Princess Road, with singer Ian Curtis looking down the camera, cigarette in hand. But Cummins isn’t the only photographer whose lens has focused on the inner city area of Manchester over the years. Other photographers have fallen similarly in love with the place. Richard Davis calls it “a mythical place”, Al Baker refers to it as “a concrete playground”, while Anne Worthington describes her time there as “like living in a hallucination.”

Hulme is a neighbourhood in Manchester a mile and a half from the city centre. Flanked by Princess Road and the Mancunian Way, the historically working-class area was home to the first Rolls-Royce workshop and the original Factory Night at The Russell Club, a precursor to Factory Records. In 1986, when student Viraj Mendis was threatened with deportation to Sri Lanka where he risked execution, it was Hulme’s Church of the Ascension and Rev John Methuen that gave him sanctuary for two years.

After heavy bombing during World War II, much of the area’s terraced housing was condemned for slum clearance in the ’60s, being replaced by the Hulme Crescents housing development in the ’70s, which was itself demolished by 1995. Today, Hulme is a mixture of residential and student housing, as the Homes For Change social housing development and cooperative continues to channel the area’s passionate community spirit.

“If you look at Hulme’s history, the fact that it’s had three versions within, what, 50 or 60 years? I don’t know anywhere else that has had that,” says Davis. And for every version of Hulme there has been a roll call of renowned photographers to document it.

Image copyright © Estate of Shirley Baker / Mary Evans Picture Library

Salford’s Shirley Baker, one of the few female documentary photographers chronicling the north from the 1950s onwards, captured the slum clearances in Hulme during the ’60s. Going out on afternoons, she would drive her Mini from Wilmslow to the edges of Manchester and walk the half-demolished terraced streets as children bunched around her.

The late photographer’s pictures show a place unrecognisable from the Hulme of today: cobbles, terraces and poverty. “People were turfed out of their homes. Some squatted in old buildings, trying to hang on to the life they knew,” Baker told the Guardian in 2012. “They didn’t have much and things were decided for them.”

Often in Hulme, it’s the walls and architecture that pull photographers in. “She was drawn initially to peeling paintwork or the graffiti,” says Nan Levy, Baker’s daughter. “She would zone in on that and then somebody would walk past. Inevitably the pictures with the people in them would end up being the best.”

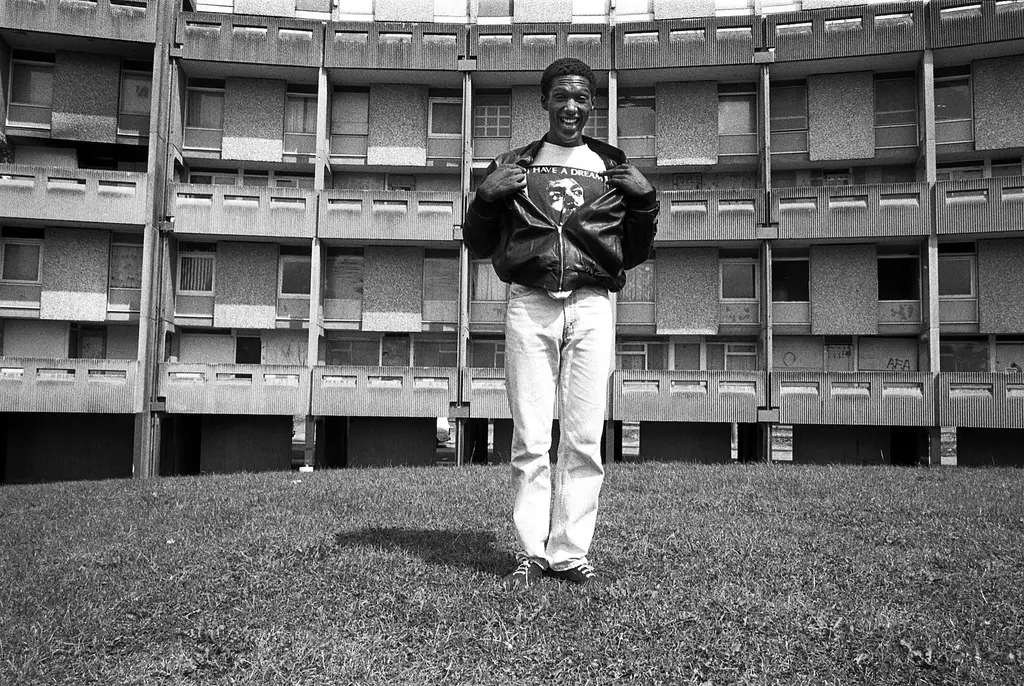

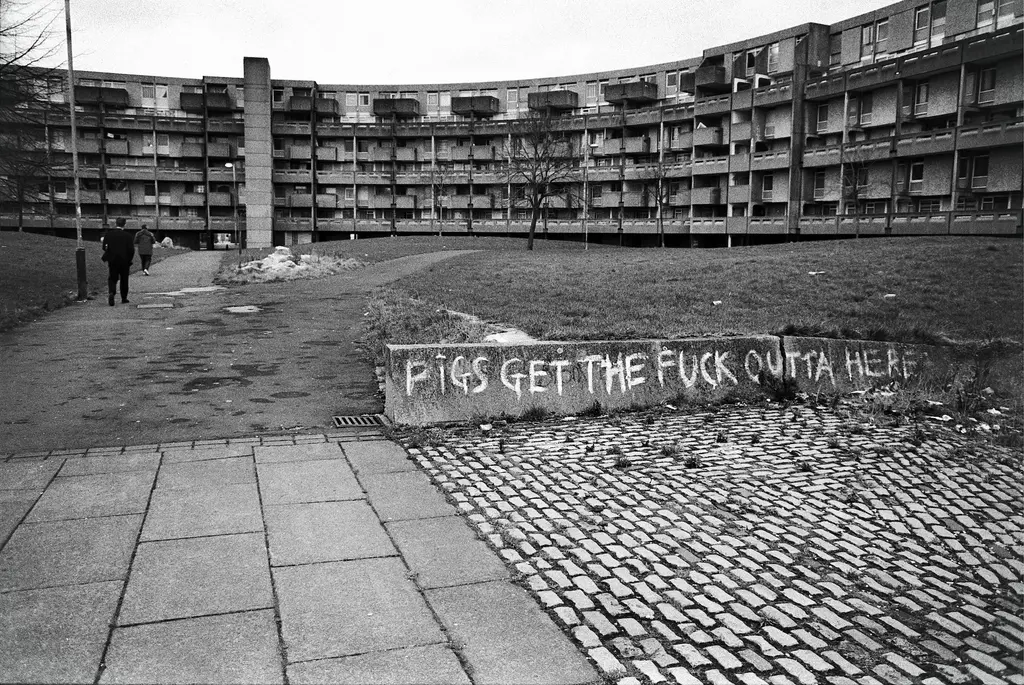

By 1972, terraced streets had been replaced by the monolithic, brutalist Hulme Crescents, the largest public housing development in Europe at the time, with homes for 13,000 people.

“Nowhere else in Manchester looked like that,” recalls British Culture Archive founder Paul Wright, who used to explore Hulme as a kid in the ’80s. “It looked more like something out of Eastern Europe or Berlin.” David Chadwick and Martin Parr were there to capture the beginning of this era, photographing fresh-faced families and a diverse community making the most of outdoor spaces.

Copyright David Chadwick, all rights reserved.

Copyright David Chadwick, all rights reserved.

Copyright David Chadwick, all rights reserved.

Copyright David Chadwick, all rights reserved.

Copyright David Chadwick, all rights reserved.

Copyright David Chadwick, all rights reserved.

Copyright David Chadwick, all rights reserved.

Copyright David Chadwick, all rights reserved.

Copyright David Chadwick, all rights reserved.

Copyright David Chadwick, all rights reserved.

Copyright David Chadwick, all rights reserved.

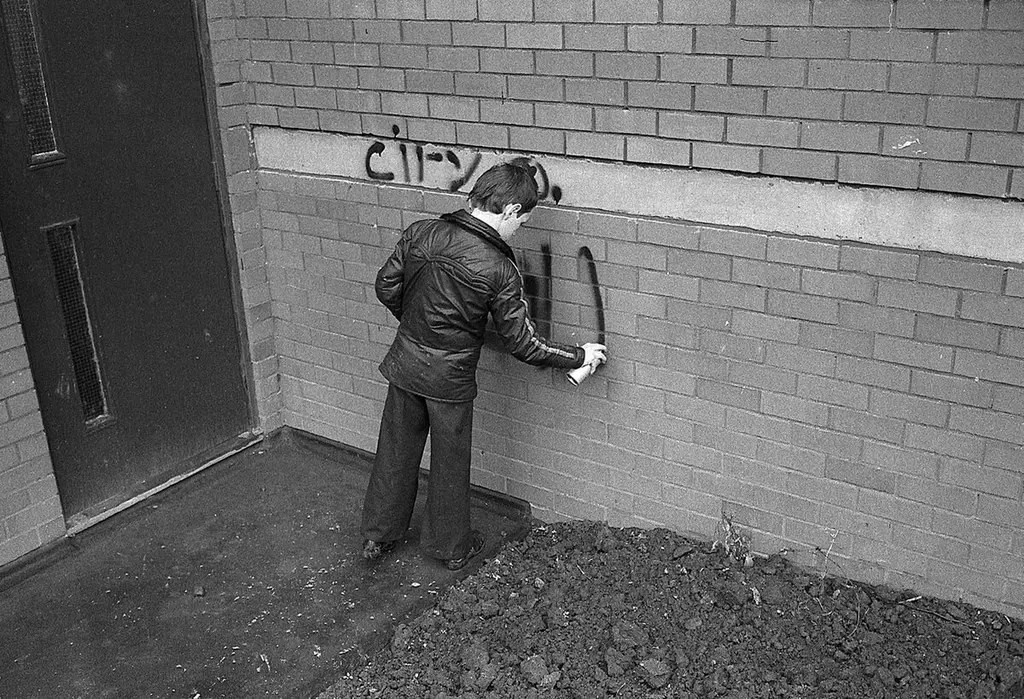

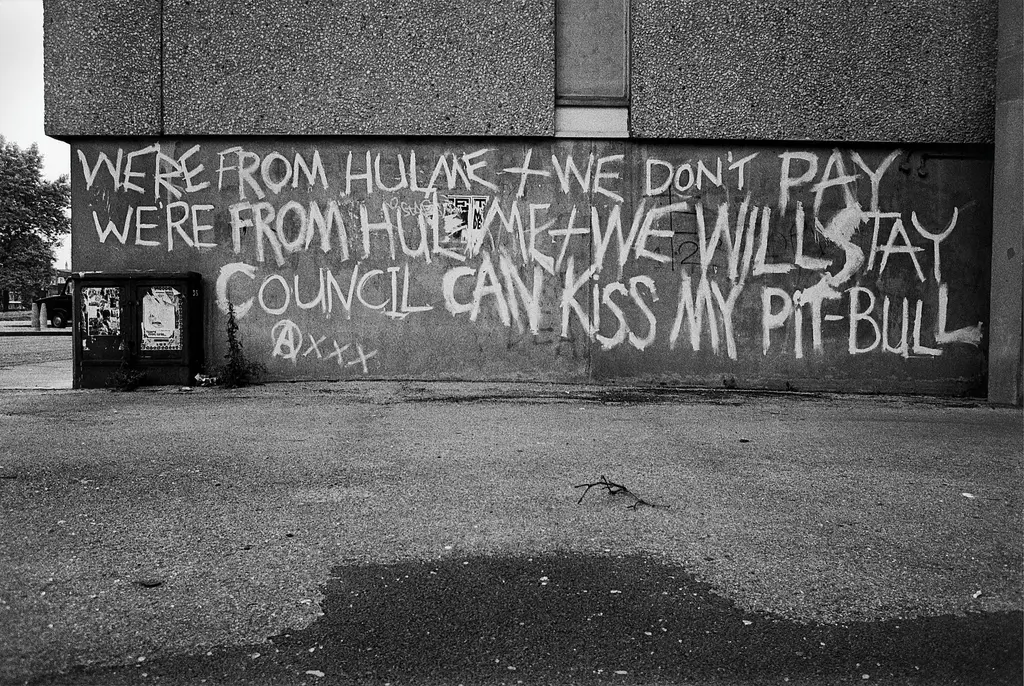

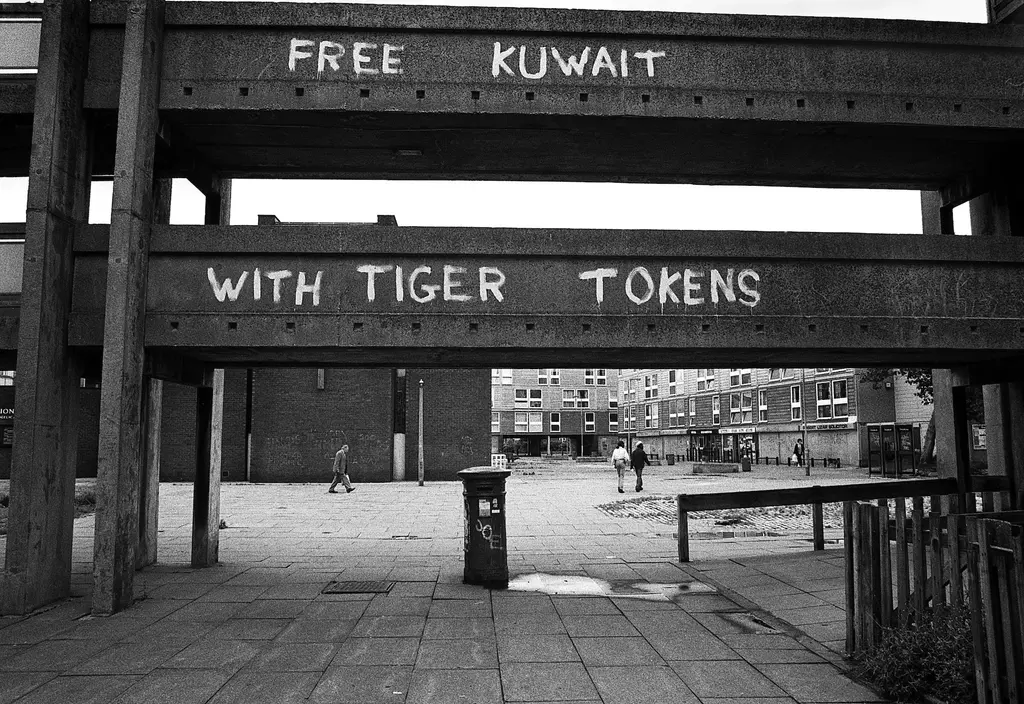

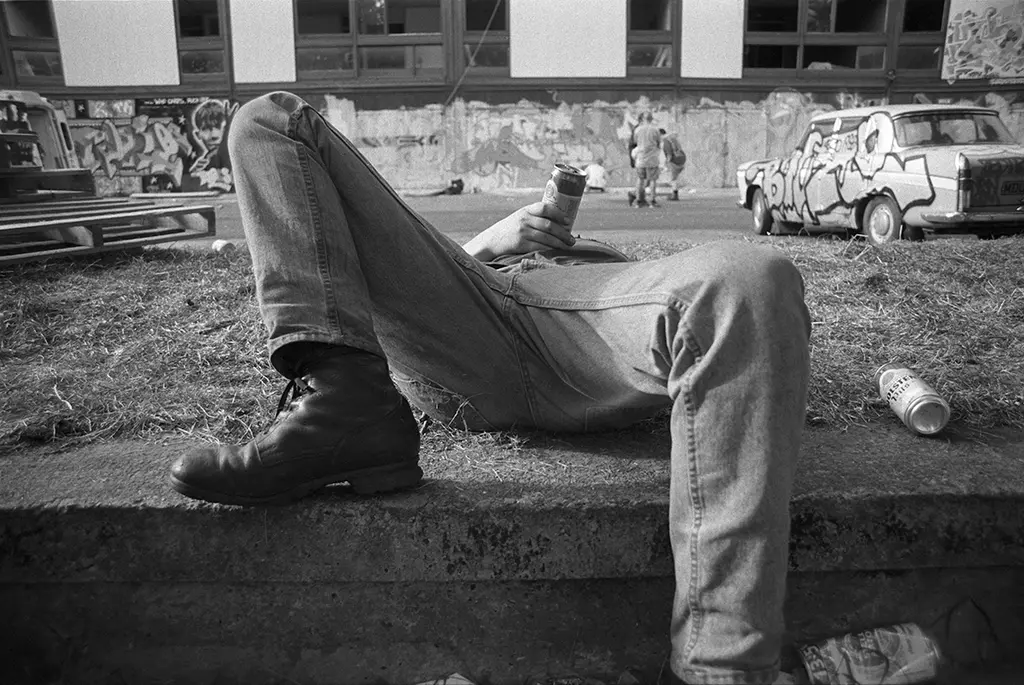

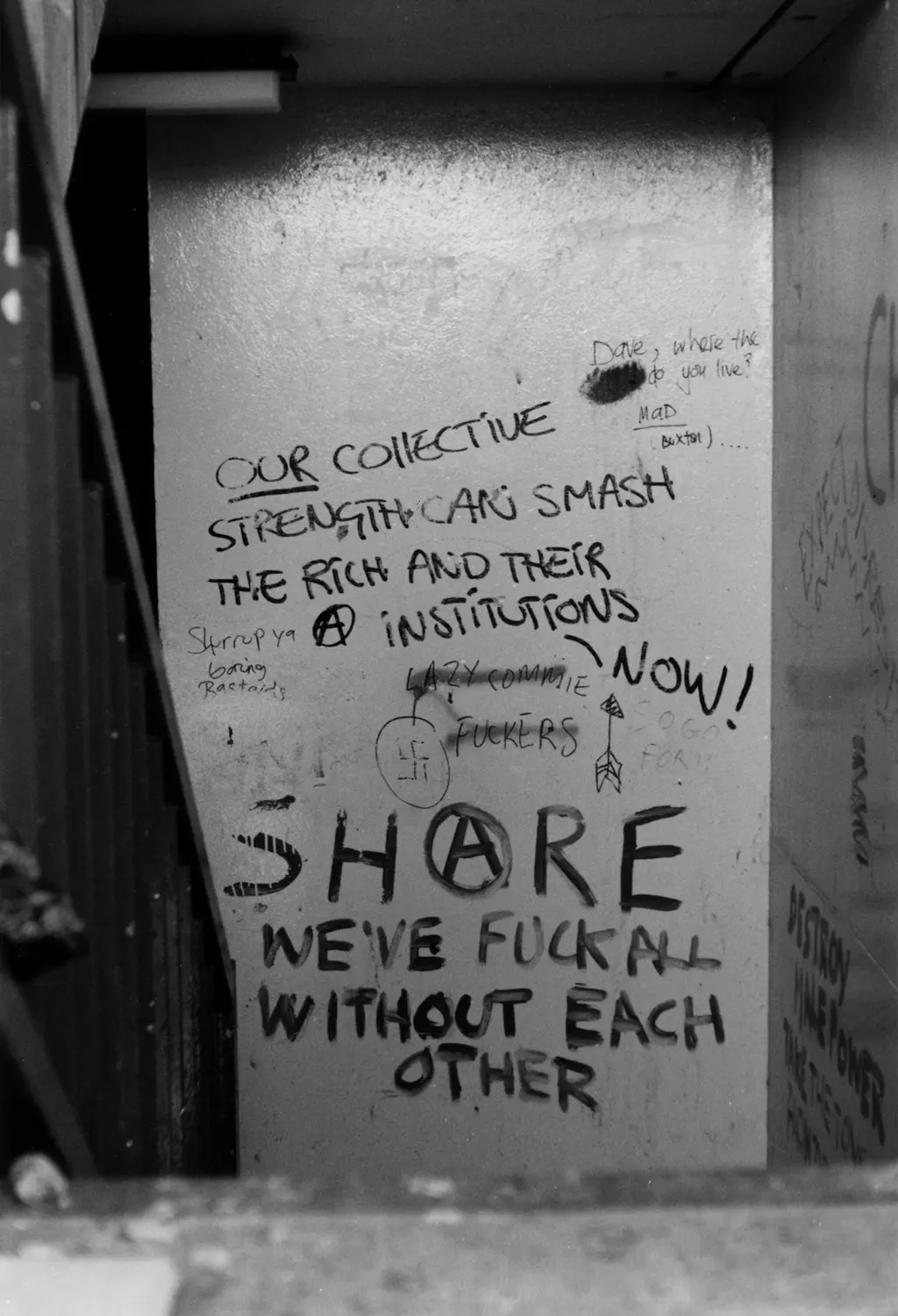

The likes of Davis followed in the late ’80s, when most of the original residents had left the badly built, poorly maintained buildings which suffered from asbestos, prolific damp and mould, as well as cockroach and rodent infestations. The council stopped collecting rent in 1984 and police avoided the area. At the time a bright-eyed student, Davis was one of a few photographers to chronicle the late ’80s squat scene whilst squatting in the Crescents himself. He describes his time there as like “getting on a runaway train.”

“It was almost like a fucking explosion going off if you were living in Hulme at that time,” says Davis, recounting the late-’80s-to-early-’90s Madchester era. “For 18 months Manchester was a global powerhouse, the centre of the world.” Rent and police-free, the Crescents were a magnet for bohemians and creatives, many of whom were associated with Tony Wilson’s Factory Records. The infamous Kitchen, a squat nightclub comprising of three knocked-through flats, became an unofficial afterparty for his Haçienda club.

Photography by Richard Davis

Photography by Richard Davis

Photography by Richard Davis

Photography by Richard Davis

Photography by Richard Davis

Photography by Richard Davis

Photography by Richard Davis

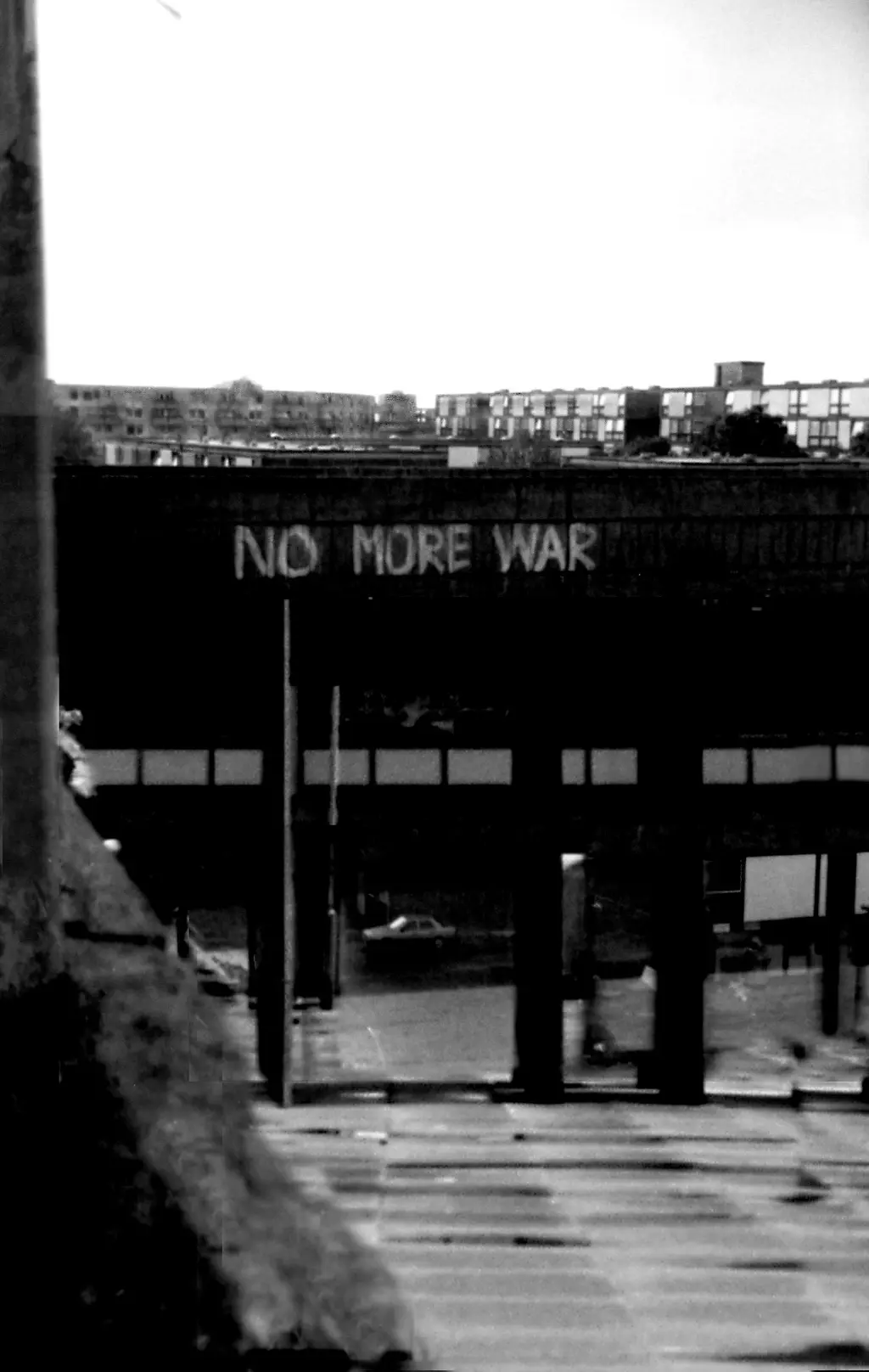

The area was a creative melting pot. An anti-establishment, fiercely independent and culturally diverse community were living in a notoriously dangerous space that had been left to bubble away. Davis shot as much of it as he could. The bands of Factory Records and the Haçienda, and the soon-to-be legends of the North West comedy scene – Steve Coogan, the late, great Caroline Aherne and Henry Normal – all passed through the DIY studio in his flat in the Crescents. In the morning, the best time to avoid being mugged, he would capture the graffiti, the politically-charged atmosphere and the people that were left behind, occupying the streets in the sky.

Photography by Al Baker

Photography by Al Baker

Photography by Al Baker

Photography by Al Baker

Photography by Al Baker

In the next decade, Al Baker photographed the punk gatherings, graffiti jams and the fledgling British hip-hop scene. “I went to MMU [Manchester Metropolitan University] in ’95 to study photography and in the first week during a welcome speech, a staff member said, ‘If you look out the window you will see a council estate called Hulme. I recommend you don’t go there. They’ll have the shoes off your feet. It’s too dangerous,’” he says. “I put my hand up at the back and said, ‘What if you live there already?’”

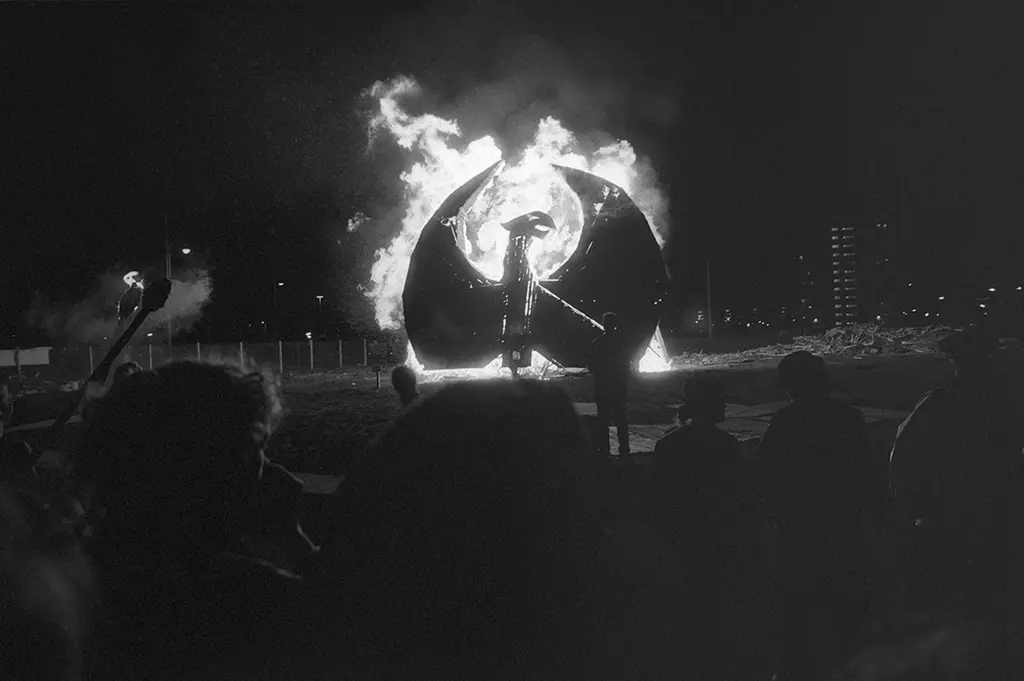

But by 1995, the Crescents had been demolished. Anne Worthington photographed the last days in the flats and the performance group she was part of, Dogs of Heaven, famously pushed cars off the top of the buildings as part of their final act.

©Anne Worthington All Rights Reserved

©Anne Worthington All Rights Reserved

©Anne Worthington All Rights Reserved

Today, all-seeing glass towers tower over Hulme. The original sites of the Crescents have become difficult to trace, as Manchester Met and gentrification encroach on the area. The visual change over three generations is almost incomprehensible.

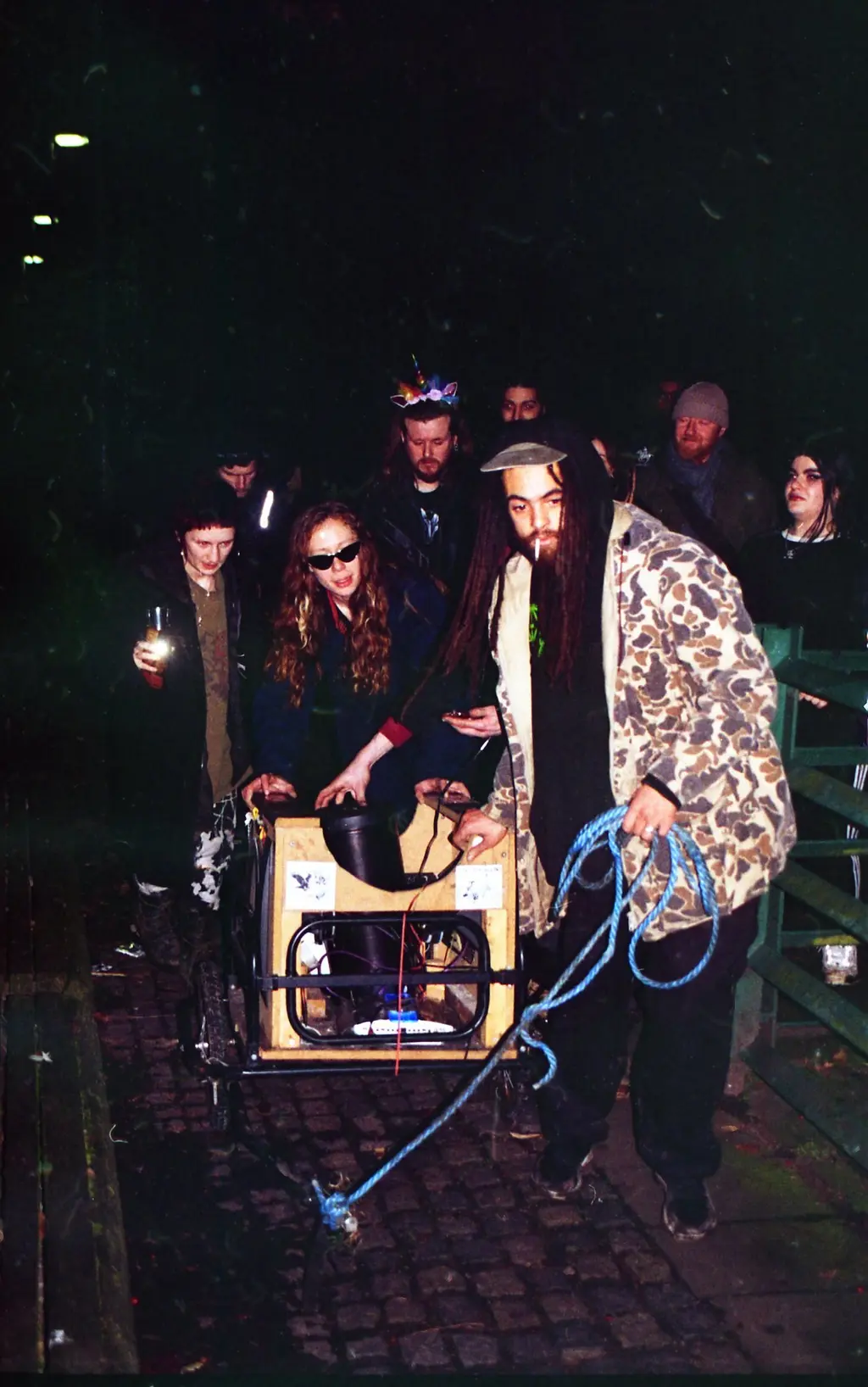

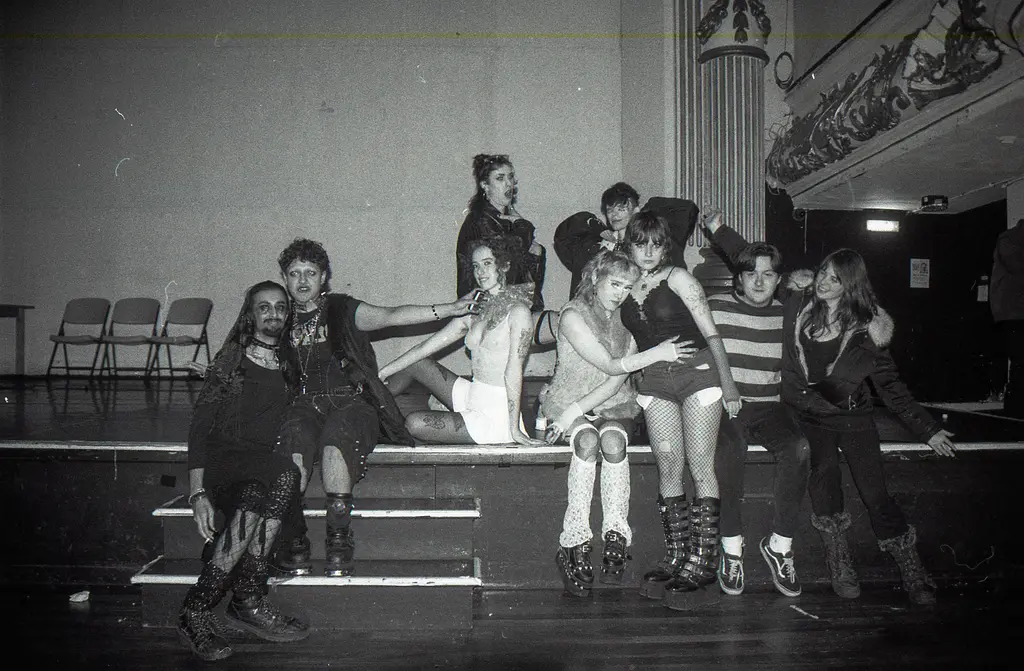

But while the scenery has changed, the spirit of Hulme remains. “You can go to the big fires we have on the park and there’s all ages. All the adults don’t give a fuck if you’re students, they just stay for the good times because it’s Hulme,” says Anni Kay, who goes under the moniker Hulme Loonies. She’s the latest photographer taking on the mantle of documenting the area.

“The local community have done loads of stuff in recent years to replicate what happened in the Crescents, to carry on the community spirit and stories,” she continues. “I love that community vibe, especially after living with my mum in Bolton.”

Growing up between her parents’ houses, Kay dreamed of being at her dad’s in Hulme permanently. Her childhood memories are of dens of thatched sticks in the backstreets, drunks in the park and a big wooden phoenix that was burned at a community bonfire. She had always been keenly aware of the area’s history: her parents lived in the Crescents together when they were younger and her mum was even photographed by Baker as part of a picture of local punks. When her dad passed away, Kay took on his flat in the “red bricks”, one of the few remaining symbols of old Hulme.

Photography by Hulmeloonies AKA Anni Kay

Photography by Hulmeloonies AKA Anni Kay

Photography by Hulmeloonies AKA Anni Kay

Photography by Hulmeloonies AKA Anni Kay

Photography by Hulmeloonies AKA Anni Kay

Photography by Hulmeloonies AKA Anni Kay

Photography by Hulmeloonies AKA Anni Kay

Photography by Hulmeloonies AKA Anni Kay

Photography by Hulmeloonies AKA Anni Kay

“Most of my photos are just [me] winging it,” says Kay. What started out as taking pictures of her mates getting pissed in the park has turned into a living record of the area. Currently in the first year of her undergraduate photography degree, she wants to carry on the legacy of Baker and Davis.

With two zines and a poster project in the making, as well as plans for a future exhibition, one day she hopes to put together a book. She feels a responsibility to the community to capture every moment, be that the area’s last remaining squatters or the bass-shuddering dub nights at Niamos, the community arts centre in the half-derelict Hulme Hippodrome.

“Years ago, people would be like, ‘Will you stop putting that camera in my face!’ Now they’re like, ‘Anni, I’m so glad you did it. I wouldn’t have remembered anything from that night’,” she says. “I feel like if I don’t go to certain events, I’m missing out on big parts of Hulme.

“I just know what I’m taking photos of is important,” concludes Kay. “I don’t see anywhere else like this in the world.”