Queer scenes and stories from around the world

New Queer Photography, Benjamin Wolbergs’ upcoming book, traces the disparate experiences of being queer in the 21st century, from Brooklyn to Berlin. Here, 10 of its global contributors answer the question: what does queer mean in 2021?

Queer is a funny old word. It’s one with an enduring legacy that’s equally liberating and politically polarising. First appearing in the English lexicon in the 16th century (meaning something strange, peculiar or eccentric), its values have been hijacked throughout the course of history. Fast-forward to the 20th century and “queer” joined “fairy” and “faggot”, becoming a derogatory term hurled through school corridors and changing rooms. But along the way, queer was reclaimed, with scholars marking the 1980s gay rights movement, at the peak of the AIDS epidemic in the US, as its shape-shifting beginnings.

By the early ’90s, queer was added into The Dictionary of American Slang as “a non-pejorative designation by some homosexuals, in the spirit of ‘gay pride’”. The establishment of Queer Nation in the early ’90s – a radical organisation combatting violence against homosexuals, would further define queer as a positive badge of honour, becoming an umbrella term for LGBTQ+ pride.

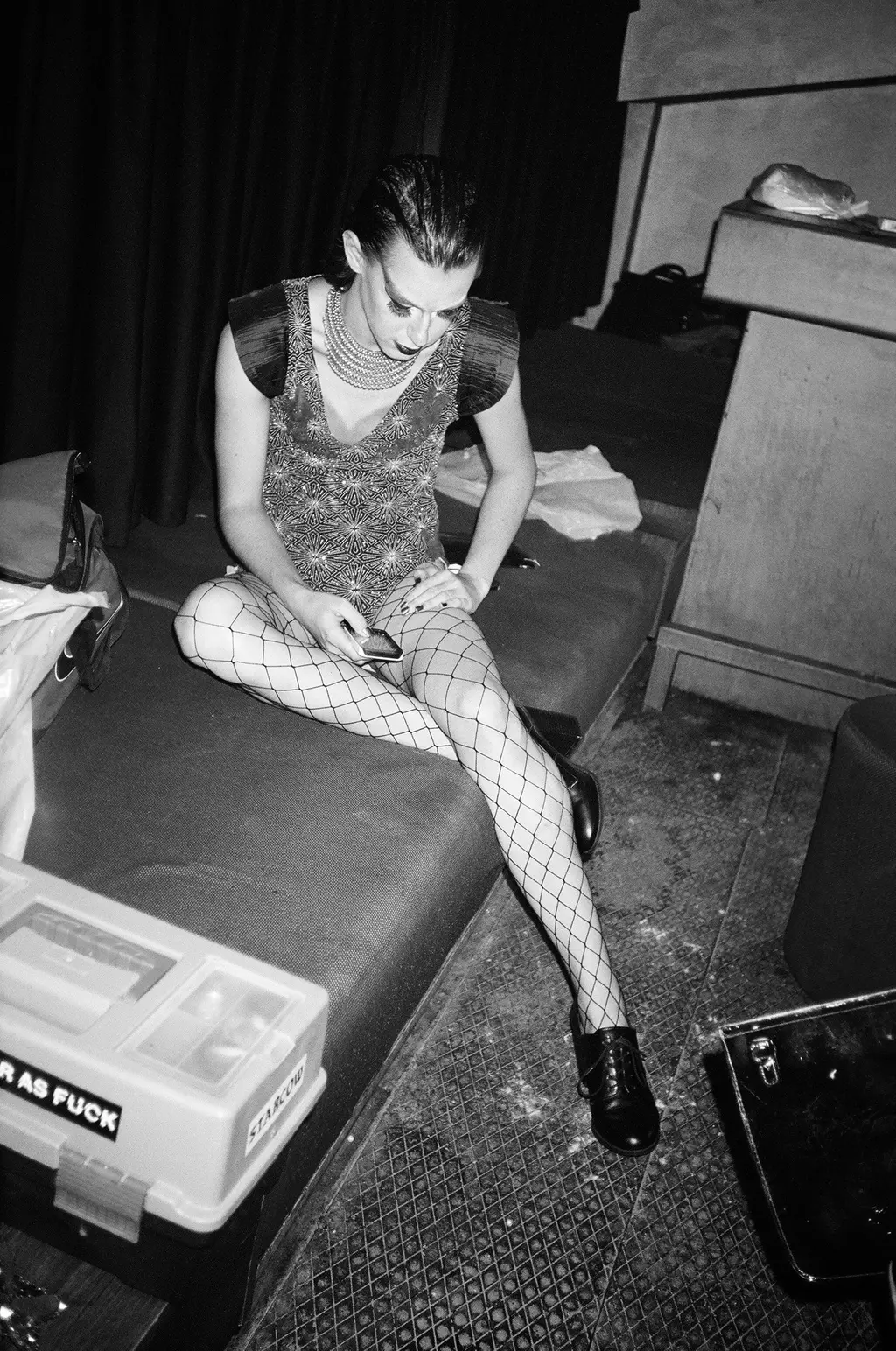

In New Queer Photography, an upcoming photobook by Berlin-based art director, Benjamin Wolbergs, queer is celebrated, and documented, by 50 photographers and writers. Each presents a mixed-media collection of images, articles, criticism and wisdom. Its purpose? To present as many diverse, queer experiences across the world as possible – from opulent drag balls in parts of Europe, to gay men living in fear in countries where homosexuality is still illegal.

“The most important thing was to tell these stories through the queer gaze without any preconceptions, and without reproducing stereotypes or clichés,” says 45-year-old Wolbergs, whose book explores diverse, alternative and individual perspectives of beauty.

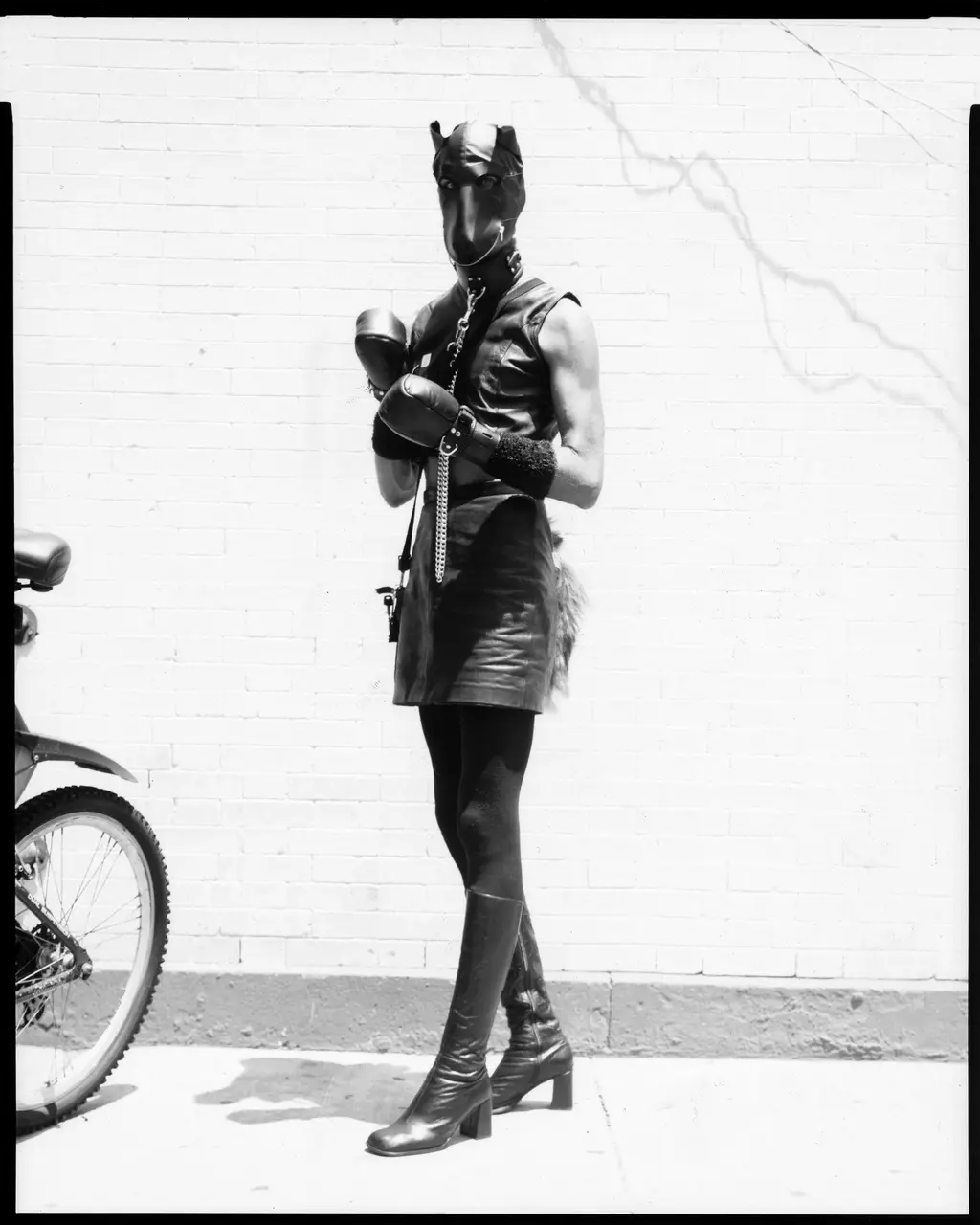

Within the 50 stories tracing queer life in 2021, you’ll find Sexugees, a polaroid series by Danielle Villasana that brutally portrays the difficult lives of trans women in Peru, and Shahria Sharmin’s portraits of hijras, a lively groups of trans and intersex people in India. Meanwhile, Benjamin Fredrickson captures a BDSM street fair in New York City, and documentary photographer Robin Hammond takes his Where Love is Illegal series to a grand total of 67 counties.

“I wanted to focus on the margins of society, sensitising people of all the injustice, discrimination and oppression that is happening [across the world],” Wolbergs says. “But I also want to celebrate pure joy, freedom and the unique creativity that – under different circumstances – can also happen within the margins.”

It would seem, in 2021, queerness has reached its most polarising pinnacle. As parts of the world accept, others only seek to erase. Arriving at just the right time, New Queer Photography celebrates the intricacies of queer history, with an appreciation for the individual experience – at times joyful, other times hostile – and an alternative perspective altogether.

“The content of this publication is loud and silent, colourful and grey, hard and soft, and all that’s in between,” Wolbergs concludes.

Below, 10 of the book’s writers and photographers share their experience of queerness, answering the question: what does queer mean in 2021?

Mohamad Abdouni, Beirut, Lebanon

I don’t think queer has a specific definition, or else it would lose all sense. The beautiful thing about the term is that you get to identify with it according to how you perceive it. Boxing it within a specific definition, gender identities or sexual preferences would rid the term itself from the freedom it holds. Queerness, to me at least, is being able to proclaim that you lead an alternative style of life, different from the one you were expected or brought up to lead.

I think it’s also important to note that I did not grow up with the term “queer”. Being born in 1989 meant I’d go through my entire adolescence and early adulthood without this word ever crossing my path except as a defamatory slur. So I’m still trying to understand what queer means, how it relates to me, and how I feel it represents me.

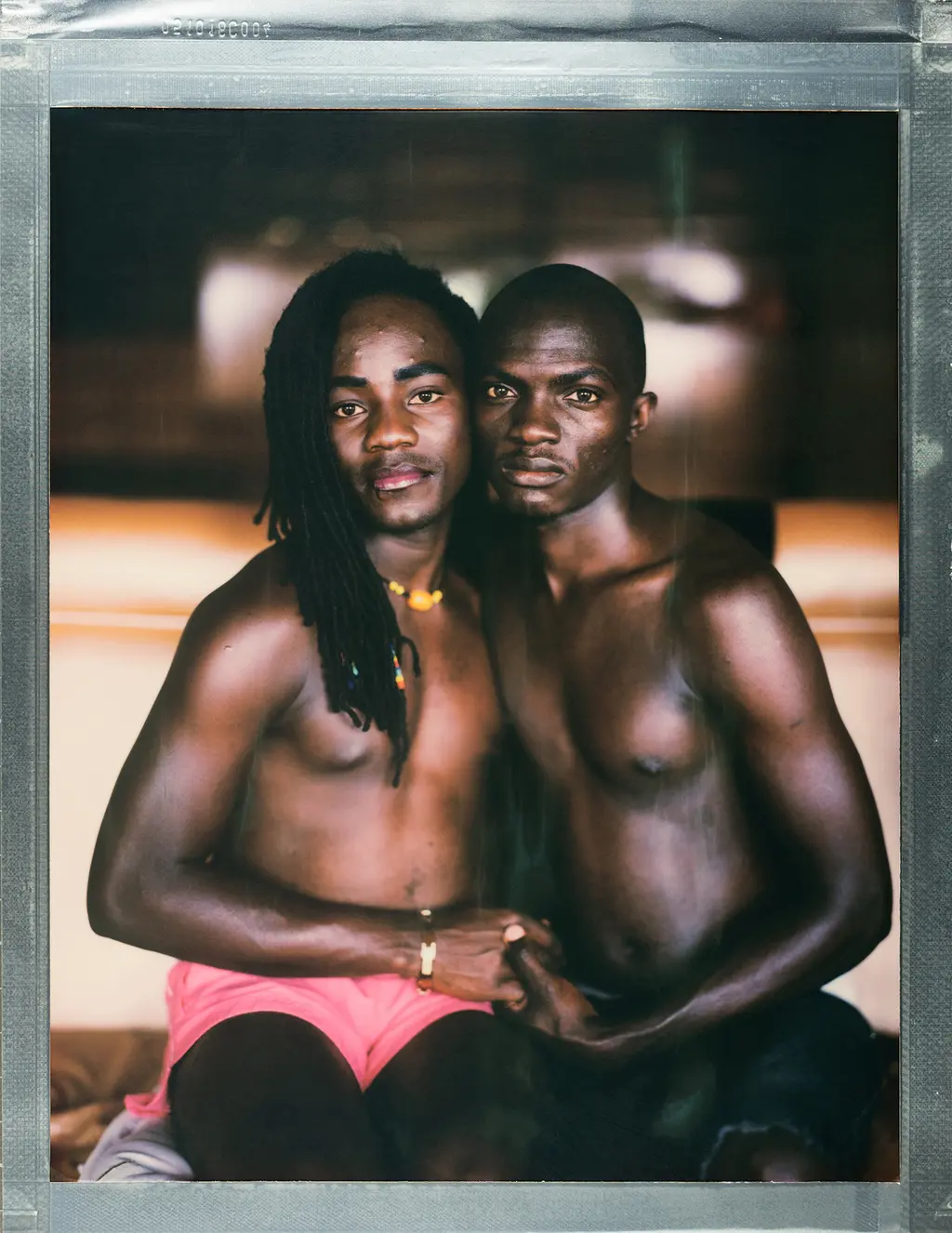

Robin Hammond, Manchester, UK

Queer today means dramatically different things to different people.

Today, 67 countries criminalise consensual same-sex conduct. At least 42 countries have legal barriers for freedom of expression on issues related to sexual and gender diversity.

And today, everywhere, regardless of the law, LGBTQI+ people are attacked because it is perceived that who they are, or who they love, is justification for violence and marginalisation.

My project, Where Love Is Illegal, has taken me to 14 countries around the world in an attempt to amplify queer stories of survival. I’ve been to northern Nigeria, to meet gay men imprisoned and tortured because of their sexuality, to Lebanon, to meet LGBTQI+ folks fleeing death threats from ISIS, and to the US, to meet trans people of colour for whom the murder rate is said to be the worst of any group in the country.

The stories I’ve documented make clear to me that life for many queer folks around the world is still incredibly difficult.

Continue reading

Despite the many stories of struggle that I have documented, what is also clear to me, is that there is hope.

In many parts of the world, discriminatory laws have been repealed. The internet and media allow for isolated queer folks to understand they are not alone. Brave activists are fighting for the lives of their communities in some of the most difficult situations. And almost everywhere, the voices demanding an end to hate and exclusion are growing louder.

Things are getting better.

When I was young, “queer” was an insult. Then, the law, my church and my family, told me that who I was was wrong. I could not have dreamt that one day I could be open about my sexuality. But since then, I’ve seen that laws can change, and people can, too.

It is my hope that in 2021, that change can become available to every queer person.

Pauliana Valente Pimentel, Lisboa, Portugal

To be queer is to be different in a heteronormative society. Queer is not only an identity but also a sense of community by LGBTQ+ people.

Here in my city, this community is getting bigger and stronger, because young people are starting to assume what they are: free from prejudice, with no fear, no shame, with power and dignity, challenging the standards concerning the identity of the human being.

This is only possible because we are living in a democratic, laic state, but in our society, we also have people, the older ones, that are still dealing with a mentality filled with racism, fascism and [resistance] against everything that is new, different and progressive. That’s why we have a fascist right-wing party rising up in our country, and that is a big concern.

Continue reading

Last year, Covid-19 meant people had to be closed inside their homes for some months, not able to hug or kiss. This situation still persists in 2021, and Portugal is even worse in terms of infected people.

For our society, this creates a sense of fear, distance and solitude. Many of my friends, queer people that I love and admire, are already used to dealing with these kinds of feelings. They know how to keep their minds strong, and are inventing new ways of being together because they have a strong sense of community.

Being queer is being dynamic and fluid minded, it is to be free and to accept the differences. I learned that the difference makes us much richer, and that we should live our own truth and beliefs, even if that is very difficult to accept by others. Because in being ourselves, we can find happiness.

Matt Lambert, Berlin, Germany

Being queer in 2021 is being more fucking unapologetic than ever.

Christopher Sherman, Toronto, Canada

The first time I saw my feelings of queerness played back to me in a visual form, I was mesmerised by how much bigger life could be. I didn’t know yet that this was my queerness making a house call for the first time – and it explains a lot about how I feel about being queer today: being broadcast onto my parents model TV (with knobs, not buttons) presented with slight fuzziness (adding to the glamour), and an unapologetic horniness. A Studio 54-style fashion and confidence that could hold a room, and could make Lady Gaga’s fashion appear demure – this was the first time I met Miss Piggy.

Under Disney ownership now, Miss Piggy has a hoof-and-mouth disease caused by corporate conservatism and the all-mighty dollar – her character is now seen through the brand lense of family entertainment. But under Jim Henson, Miss Piggy was a queer kaleidoscope for many. She was the closest energy I could relate to, out glamorising even the glamazons of the era, who would visit The Muppet Show weekly. I knew then I wanted to be a pig living big.

Continue reading

I have always found a model for a better world, and queerness in The Muppets. It brings together frogs, pigs, bears, and whatever, and collectively change the energy of the world through celebration and joy. If you want a visual representation of how my queerness feels inside me today, watch the Broadway musical number in Muppets Take Manhattan – or Falcon’s Best of Al Parker.

On another note, I can also confirm there are a lot of pigs in fashion.

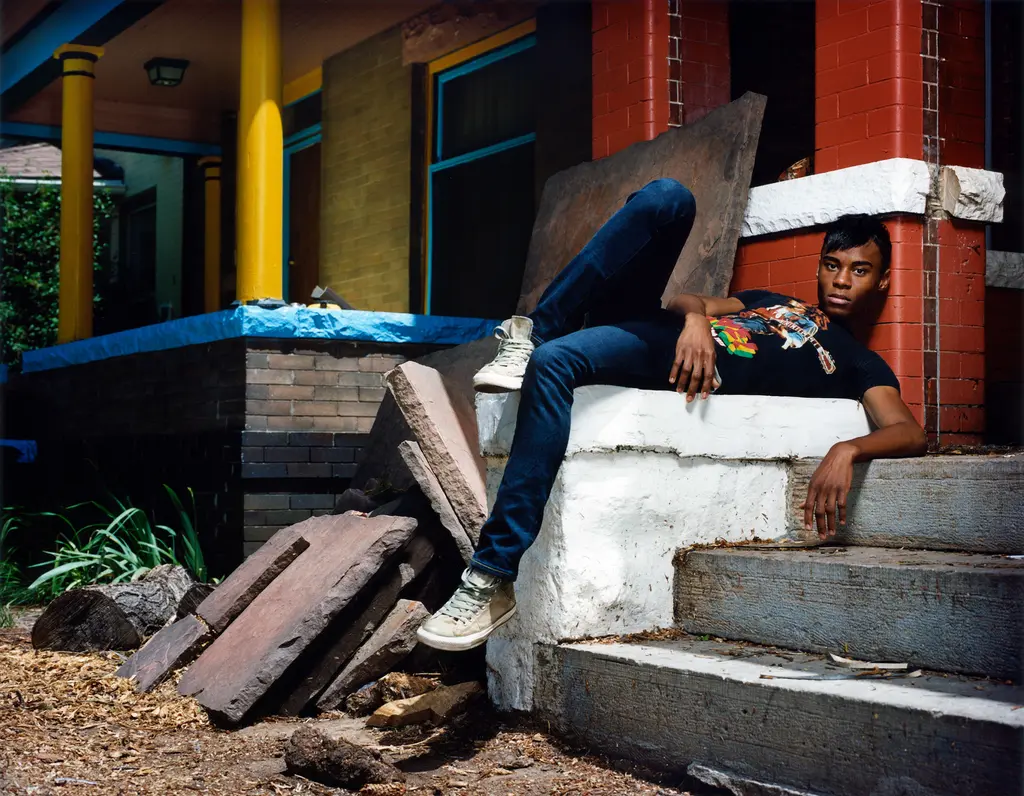

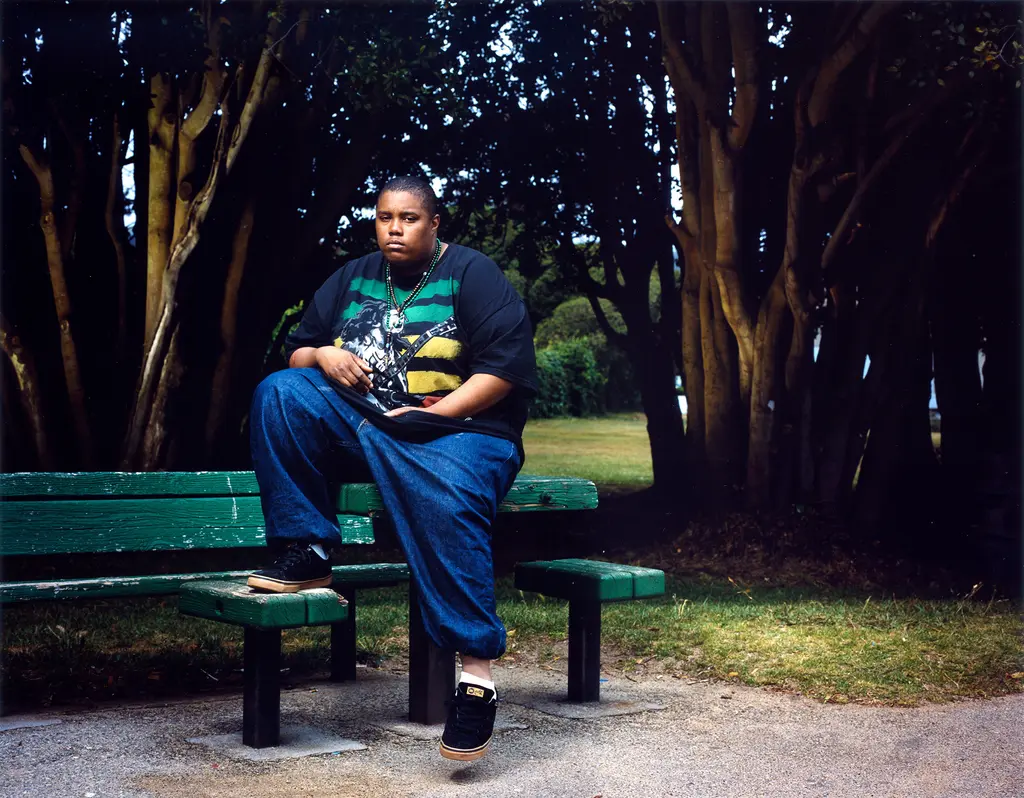

M. Sharkey, New York City, USA

As a gay man who came of age during the late 1980s and early ’90s, it’s been very interesting to closely follow the evolution of the word “queer”. I know the expression is older than I am but I like to think of “queer” and I as not just contemporaries but compatriots, as well; we sort of grew up together and “queer” from 40-years ago resembles itself probably as much as I resemble my own childhood self.

I remember being in elementary school in rural Colorado and living in mortal fear of being called queer. Like “faggot”, it was delivered venomously and meant only to humiliate and provoke, as in: you fucking queer! These types of assaults were almost never private, but hurled within earshot of as many peers and adults as possible. Like chum to a swarm of sharks, the aim was to gather aggressors. If, god forbid, the word stuck, you might be looking forward to a nightmare of years of soul-crushing humiliation. Thankfully, this did not happen to me but I do wonder now how much of my personality is in direct response to actively avoiding such a fate. Words have power.

By the time I was finishing high school, with the AIDS epidemic in full-swing, the activist group Queer Nation formed in response to LGBT(Q) violence and queer was reclaimed, as so many pejoratives are. My years at college coincided exactly with the word entering the lexicon of higher education and academic theory, presumably because of its power to still be offensively shocking. Academic discourse is by design exclusionary so if you were “in-the-know”, only then would you understand queer’s subversive potential (otherwise, you might still find yourself on the receiving end of a very hurtful slur).

Continue reading

Indeed, when I began my Queer Kids project in the spring of 2006 most (queer) people understood the term to be both subversive as well as affectionate, though not everyone. I remember receiving heated comments criticising my use of the word. How could I be so cruel? they asked. Of course, I was pleased to learn that the term still had some punch since by this point it had been in wide use for many years. Then, within the last decade or so, and rather magically, queer began to occupy a singular place in the language. Identity politics – and the culture at large – seem burdened by a multiplicity of labels, ad nauseam, but queer somehow manages to encompass a great many, more precise proclamations. I love it for its efficiency but also because you still can’t quite pin it down. Is this queer? Is that? It defies a concrete definition and yet almost anyone would be well within their rights to state: “I am queer”. You might wonder, as I do, how long can this last? The answer is not forever. I’ve attended more than one-panel discussion where the sole purpose was to imagine what a post-queer world might look like and once within, what the language might sound like.

Now, in 2021, after several years of intense political rancour here in the US and a reckoning with our racist past and present of a magnitude I have not experienced in my lifetime, the upheaval of “normal” life due to a global pandemic and finally finding ourselves at the crossroads of a potentially catastrophic climate crisis, I like to envision a queer world where everything you previously understood to be true or right is reexamined, reimagined and rebuilt. Queer people have learned a great deal over the past half-century about how to dismantle systems of oppression in order to fully become our true selves. My hope is that this hard-fought-for experience and wisdom gives us the ability to overcome all of these obstacles and see more clearly the great potential of humanity to come together and care for each other.

Bettina Pittaluga, Paris, France

Queer in 2021 starts a conversation. It’s about how you love, not who you love. It’s being free to be yourself. I think we all need that kind of inclusivity, privacy, and love in our lives.

Benjamin Fredrickson, Brooklyn, New York City

Queer means encouraging sex positivity within our community – that encompasses a broad spectrum of gender identities and sexual orientations – to make room for everyone. From my perspective, as an HIV positive gay man, to be queer is to be unapologetically authentic and to demand inclusion where there is none. My visual voice is photography, and through that, I choose to document and celebrate my community and those around me. By showing up for other people, I learn to show up for myself; that’s queer.

Huw Lemmey, Barcelona, Spain

I dream that queer means polymorphous perversity, and against the infinite taxonomies of desire. Alas, I suspect in 2021 it now means something else.

Ben Miller, Berlin, Germany

Increasingly little, if I’m being honest. If I’m being hopeful: a horizon, as Josè Esteban Muñoz once said. Something to work towards. Something you do, as well as something that’s done to you. Labour. Everyone has impulses they can encourage or suppress. Let’s all stop, as much as we are able, pushing away the queer and trans parts of ourselves. In 2021, I’m more interested in how and what people are doing with “queer”, within the constraints of class and race they live in, than [I am with] how and whether they identify with it.

New Queer Photography is available to purchase at verlag-kettler.de

Follow Benjamin Wolbergs at @benjaminwolbergs