Go on – phone in sick and go to a free festival instead

Seana Gavin’s new exhibition Spiral Baby celebrates the revolutionary togetherness of Spiral Tribe. It’s good for you.

On 22nd May 1992, a rave started and lasted a week. There was moral panic, police brutality and between 20,000 and 50,000 attendees. The rave was Castlemorton in the Malvern Hills, Worcestershire – and it was the involvement of Spiral Tribe, a free party and sound system collective, that helped turn it into one of the most iconic party moments of the 1990s.

Joining Spiral Tribe a year after Castlemorton was Seana Gavin: an artist and photographer who spent much of her years travelling across Europe, attending raves and living nomadically. “I was 15 or 16 when I met them and started attending their parties,” she says. “I soon shaved off all of my hair and became a ‘spiral baby’, as the phrase went.” It was there that she began documenting the world around her – the photographs she took spawning her upcoming exhibition.

While it’s easy to think of raves as mere hedonism, for Gavin it was everything: “an alternative outlook to society, the world and a complete way of life,” as she puts it. During the ‘90s, when conservative rags ran headlines that read “£12 TRIP TO AN EVIL NIGHT OF ECSTASY”, and the BBC banned ‘smiley’ tracks altogether, Spiral Tribe were living their lives exactly how they wanted to, avoiding the status-quo and making their own set of rules. 20 years after Gavin left the scene, her exhibition tells the story of the freest, most self-generating party revolution the country – and continent – has ever seen.

How would you describe Spiral Tribe?

Spiral Tribe was a free party sound system collective originating in London in the early 1990s. They are well known for their involvement with the iconic Castlemorton week-long festival which took place in the British countryside. Before the days of mobile phones, 20,000 to 50,000 people attended the party. After violent attacks by the police at raves, a two-year court case, and the enactment of the draconian Criminal Justice and Public Order Act in the UK, the collective decided to head to France to continue their mission of putting on free teknivals (techno festivals). Numerous sound systems stemmed from this scene who continued to put on illegal raves in warehouses, derelict factories and post offices across London and in fields and quarries beyond the city. They also joined the Spirals beyond the UK.

What were the main differences between the raves when you travelled to other countries?

The parties in Europe were slightly different to the UK, just because by then people had committed to it as a full-time nomadic lifestyle. But they evolved from the same crews of people, so there were fundamental similarities. I guess there was more freedom when the scene was brand new over there. When Teknivals were held in small villages across Europe the authorities had never witnessed anything like it, so didn’t know how to address it or deal with it.

How did people hear about the raves back then?

In London, there was a party line number that you had to call last minute on the night to get the location. They would sometimes be hard to find and in obscure locations in industrial areas and on the outskirts of the city.

Seana Gavin’s ultimate rave playlist

1. The Orb – Little Fluffy Clouds

2. Aphex Twin – On

3. Speedy J – De-Orbit

4. Spiral Tribe – FFWD The Revolution

5. Drum Club – You Make Me Feel So Good

6. Eat Static – Lost in Time

7. 2 Bad Mice – Bombscare

8. Spiral Tribe – Sirius 23

9. Human Resource – Dominator

10. Robert Hood – Detroit

Can you share a stand-out moment from your free party days?

After one summer of Tekno travelling across Europe when I was 18, I ended up staying in a squat in Berlin for three weeks. I was left with just £20 in my pocket when I had to get back to London, so me and my friend had an insane four-day trip back, bunking trains, hitching and sleeping in strange locations. Every day was an extreme combination of good and bad luck. We ended up in Rotterdam where we had to kill time all night before trying to catch the ferry in the morning. So many things happened that night, including me being physically attacked by a toilet attendant in the train station followed by befriending a group of kids who took us to an American bar and generously gave us a bulk of cash to pay for our ferries the next day. It was quite an adventure!

What do you think of the rave scene now?

To be honest I have no idea what the scene is like now. Teknivals still happen across Europe but it can never be as underground as it was during my time. The underground can’t exist in the same way and it always feels different when something is new and exciting. Raves cannot be repeated in the same way because the world and social climate is so different.

What message are you hoping to get across with Spiral Baby?

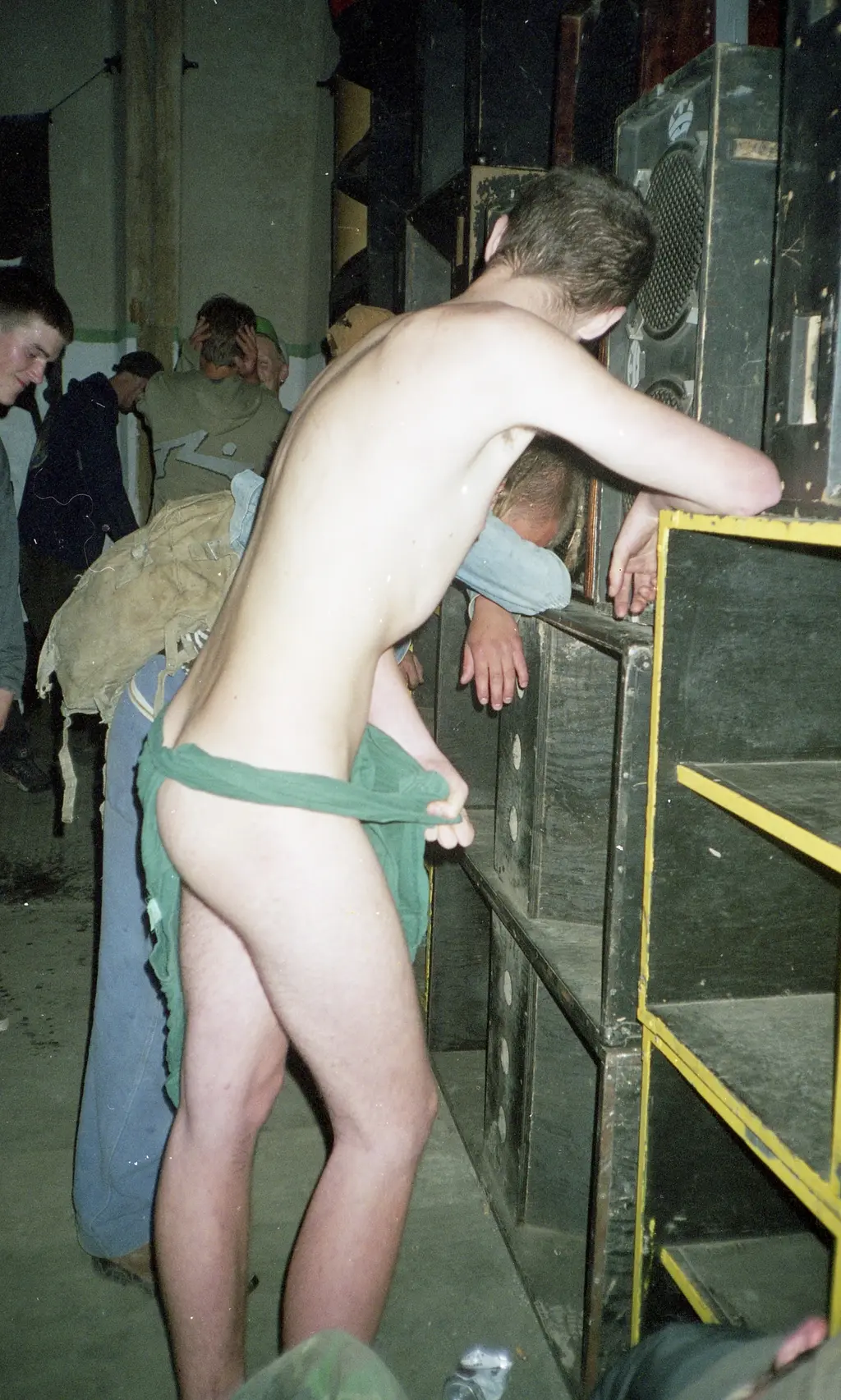

The photographs capture the rave’s unusual locations, the journeys, the build-up and aftermath of the parties, and the characters and friends who defined the scene – many of which are no longer with us. The party culture of fast, heightened living came with its consequences.

This show is also a tribute to my friend Ben, who passed away at a party in France. Some of the journeys captured were taken while travelling in Ben’s converted army truck. He lived and breathed this lifestyle during his stunted time on earth. These photographs, like my memories, have gritty undertones – sometimes a combination of shocking and humorous moments caught by chance, altered states of mind, and some surprisingly peaceful moments of calm in-between moments of extremity and hedonism. This exhibition demonstrates the ethos was more than a night out. It was an alternative outlook to society, the world and a complete way of life.

Spiral Baby will be shown at Galeriepcp, 8 Rue-Saint Claude, Paris, 7th June – 27th July