Swampy: ’90s eco-warrior hero returns

He was the most famous climate activist in the UK, fighting the good fight two decades before Extinction Rebellion. Then he went to ground – until now.

Culture

Words & photography: Jak Hutchcraft

The rural train station in west Wales, six hours by rail from London, is quiet, surrounded by woodland and soundtracked by birdsong. Standing in the car park is a bloke in muddy wellies, green work trousers and a t‑shirt. He could be anyone, a middle-aged countryside dweller with a job on the land.

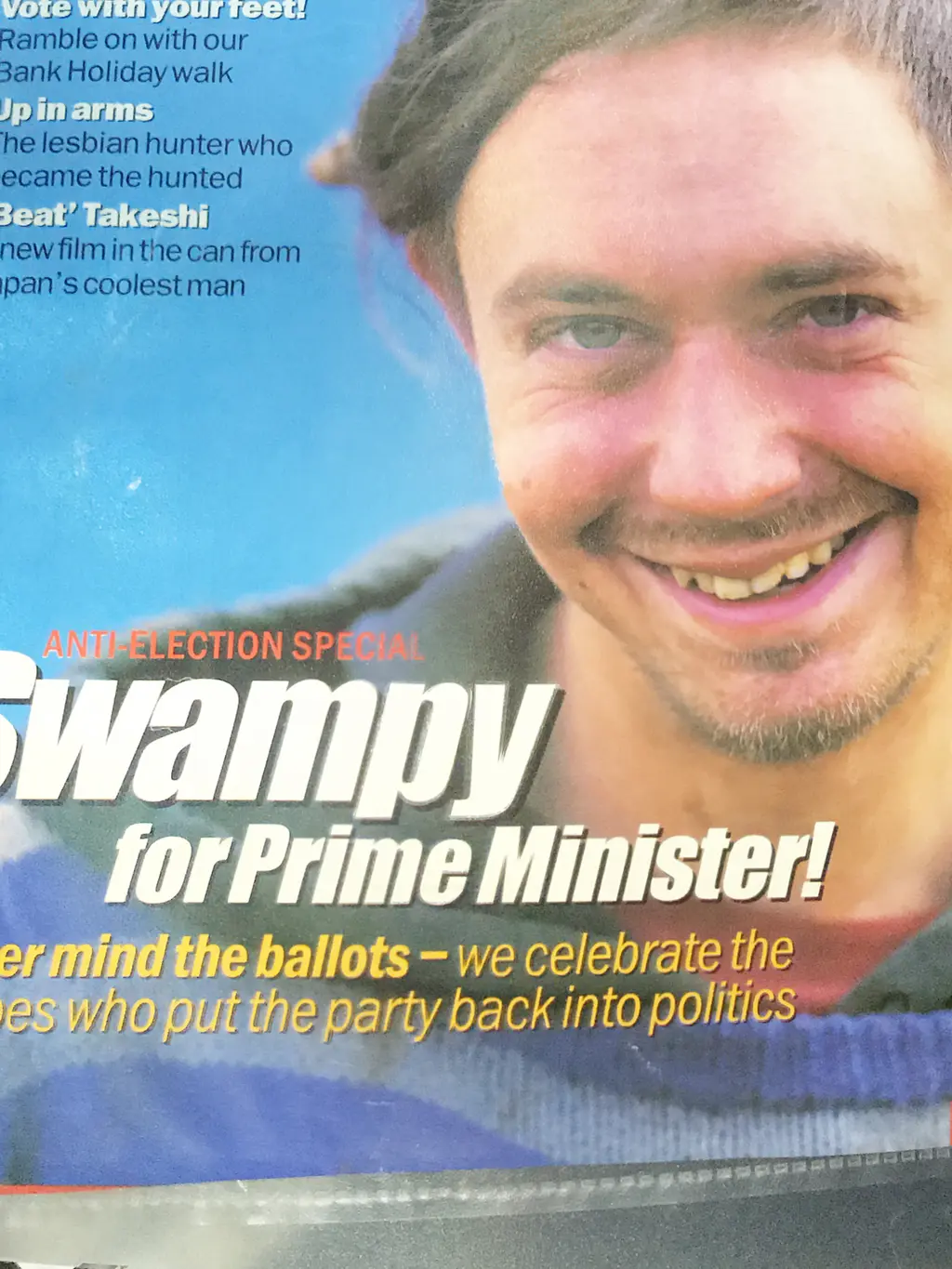

But in 1997 he was an odd kind of celebrity, a familiar figure on TV news bulletins and newspaper front pages.

This is Dan Hooper. Twenty-three years ago he was the tree-climbing, tunnel-digging, dreadlocked face of green activism, a 23-year-old accidentally thrust to the forefront of the fiercely fought campaign to halt the expansion of the A30 in Devon.

Back then, no one called him Dan. He was Swampy, and he was the most famous eco-warrior in Britain.

Then he went to ground, shunning the personal publicity and attention that briefly made him the most well-known figure in British environmentalism – until now.

Hooper has spent the last 16 years living off-grid with his family in an alternative community called Tipi Valley. The vast eco-village is the largest and longest-running of its kind in Britain, and comprises tipis, yurts, hand-built houses and turf-roofed round huts.

Still, he’s no fundamentalist Deep Green shunning all forms of technology. “We all have to drive occasionally,” he explains, contemplatively, as we make our way out of the small town and into the hills, stopping to pick up a neighbour. “Unfortunately there isn’t a good enough public transport system, especially rurally. So you just try and get as many people in your car as possible.”

The roads grow narrower and my phone signal disappears as we approach our destination. The commune, sprawling across 200 acres, is home to around 80 adults and children. When Hooper agreed to this interview, he invited me to stay the night with him and his family. In gratitude and by way of return, I offered to help out where I can.

After we park at his neighbour’s home, we grab a wheelbarrow, fill it with firewood and push it to the eco-friendly, sturdily constructed yurt that he, his partner, Clare, and their friends built over a decade ago. Inside it’s cosy and lived-in. I leave my boots on the mat next to several pairs of wellies and take a seat at the dining table. Three of Hooper’s children and a neighbour’s child play in and around the house. It’s unconventional but at the same time homely, familiar and, well, normal.

“We were just doing what we had to do. I happened to have a silly name and be the last out of the tunnel. It just fitted with what the media wanted to see, I think”

Hooper’s previous life as Swampy was formed in 1996, at the Fairmile protest in Devon. An activist group built networks of treehouses and tunnels in an attempt to block the upgrading of a section of the A30, which runs 284 miles southwest from London, all the way to Land’s End. As the opposing sides dug in for a final confrontation, Swampy and his fellow activists stayed locked in the tunnels for seven days and nights, going on hunger strike for the last four days. They were eventually forcibly removed by a team of 200 police officers, bailiffs and confined space rescue specialists in January 1997.

When they emerged, with Swampy as the last man standing, the press were waiting.

“We were just doing what we had to do,” Hooper recalls over a glass of wine at the dinner table. “I happened to have a silly name and be the last out of the tunnel. It just fitted with what the media wanted to see, I think.”

His boyish good looks, baggy woollen jumpers and eye-catching hairdo – basically, a dreadlocked fringe that reached his chin – made him an unwitting posterboy for the movement. After eviction from the tunnels, his life changed overnight. He appeared on an episode of Have I Got News For You?, at the time the youngest ever panelist on the satirical quiz show. Journalists and TV producers began hounding him and his family, and would do for years to come.

From school kids to pensioners, politicians to artists, everyone knew the name Swampy. For some, he was a role model and symbol of positive change. For others, he was the butt of a joke. For Hooper, it was head-spinning.

An adherent of vegetarianism and animal liberation, his interest in climate activism rose when he read about the Free Party and New Age Traveller movements of the late ’80s and early ’90s.

The former emerged from the Acid House music scene and revolved around free illegal raves and parties, most famously the week-long Castlemorton Common festival in 1992 which attracted an estimated 40,000 people to rural Worcestershire. The latter shared beliefs and values with the ’60s hippy counterculture and anarchism, with travellers largely living in converted vans, buses and mobile homes.

“My mum used to get the Daily Mail and there were all these hateful articles in there about [the movements]. I remember looking at them and thinking: they look really good!” he laughs. “Even though I didn’t go to many free parties back then, I just really liked the look of it all.”

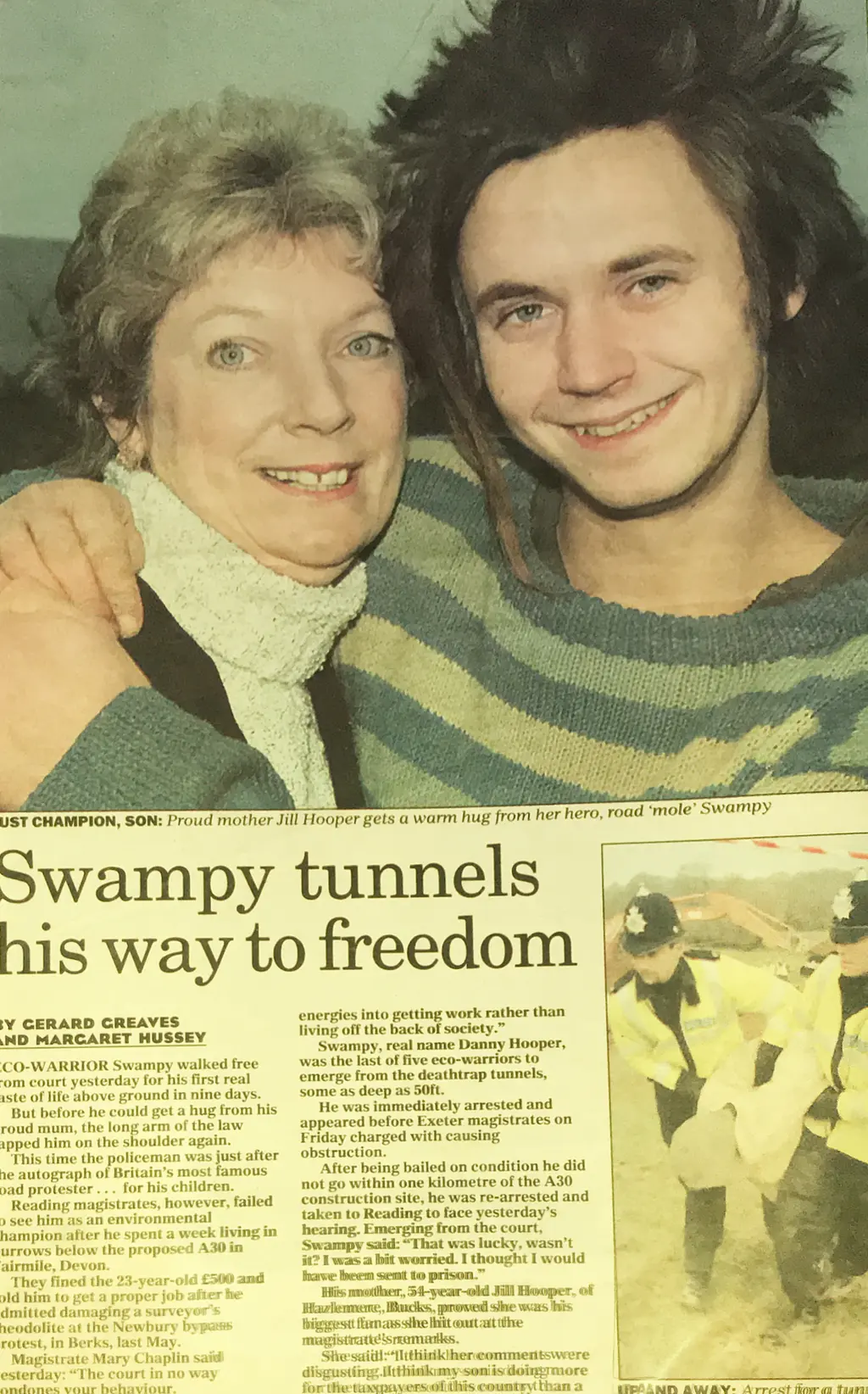

His mum was initially worried about her son’s career in activism, especially after his early arrests, but she eventually came round and even did interviews and photoshoots with the tabloids.

Before he was Swampy, Bedfordshire-born Hooper went from working in a toyshop to a call-centre market research job. “It sounds bad but it was flexible hours. And the main thing was I could dress how I wanted because it was on the telephone. I could have long hair and stuff… I could be more myself.”

Then Hooper moved to Exeter and became involved with a group of hunt saboteurs. His life was now dedicated to activism and his first stop was the protest at Fairmile.

“We started digging at Allercombe,” he says of the hamlet south of the A30, “and I thought: ‘This is really good – how the hell are they going to get us out of this?’”

His eyes light up as he describes the scene with keenly remembered, passionate detail and we flick through his old photos and the newspaper cuttings collected by his grandma.

“We tried to make the tunnels as small as possible – we had to wiggle through these small tunnels into chambers. When you’re digging small tunnels it’s really scary. And when it’s really small, you sometimes have to go in with a bricky’s hammer and drag the soil back through. I used to have an air-pipe and it would get clogged up with soil, so I’d have to suck the soil out, spit it out and take a drag of air.”

The eco-message is, and always was, the most important thing for Hooper. So the sudden onrush of celebrity was confusing, to say the least.

“A journalist from Have I Got News For You? said they’d give me £500 to go to London to do the program. It seemed like a lot of money, and it seemed like a good idea at the time. But afterwards I thought: why did I do that?”

He admits he was terrified on the show, which is why he barely spoke.

“There was an audience, and there were hot cameras and lights and everything. I was just like a rabbit in the headlights. It wasn’t where I wanted to be.”

This was one of several occasions when the media bribed him with cash for interviews and other schemes. Like the time a magazine convinced him to shave off his hair and wear a suit for a fashion shoot.

“It was horrible, I don’t know why I agreed to it,” he remembers with a grimace. “I had just walked out of court after getting out from the police station – I was being done for criminal damage for Newbury,” he says of another bypass protest. “I had a £500 fine, which doesn’t sound like a lot but I didn’t know how I was going to pay that. A journalist said: ‘We’ll pay your fine if you do this’, and I said: ‘OK!’ I felt like a right twat! I was really stressed, I hated doing it and I wish I hadn’t.”

The weirdness didn’t stop there. He was asked by a music producer to record a version of I Am A Mole And I Live In A Hole under the name Swampy & The Swamp Girls. This time, mercifully, he declined. Later in 1997 a vegetarian eco-warrior called Spider arrived on Coronation Street. Although the soap’s creators denied basing the character on Hooper, his green activism and shabby clothing was instantly recognisable to many viewers. There was even a Judge Dredd comic character based on him called Spawny.

By the time of the 1997 Manchester Airport protest, he and his crew had to build a fence around their camp – partly to keep out the police, partly to deter the rabid pack of tabloid journalists.

“It was like a wave,” he sighs. “Once it got going it was hard to stop it.”

Not long after, his celebrity status began to cause rifts within between him and the other activists.

“It was quite upsetting. I realised that we shouldn’t have that – we don’t want that personality culture, it doesn’t help. Plus, there weren’t loads of extra people protesting because of it – there were almost less people involved afterwards. The momentum seemed to die down after A30.”

When Hooper decided to step away from the limelight, he had to make some big decisions.

“I changed my name back to Dan. Swampy wasn’t me any more. I carried on protesting but I wouldn’t talk to the media. We did actions that could have probably done with a bit more media publicity, but I never called them.”

“Living in tipis in Wales? That’s mad! But the more we visited the more we were like, actually, it’s quite nice here”

These days he lives by his beliefs with his partner Clare and their three young children (Hooper’s eldest child from another relationship lives elsewhere). Water that they redirect and filter from streams and electricity provided by solar panels are two of the ways that they live more harmoniously with the Earth. They also grow their own vegetables, compost their waste and their home is well-insulated and built entirely from natural objects.

Even his “day job” fits the brief and the belief: Hooper works in forestry. And while he recognises the scale of the climate emergency, he retains a fighting spirit. “I’m a positive person so I think that we’ll turn around climate change. But we’ve got a big fight on our hands.”

Climate activism has changed a lot since the mid-’90s. The movement was smaller and more bohemian then, but the bold tactics of the time made up for the fewer feet-on-the-ground. The Newbury bypass protest in 1996, for example, saw protestors chain themselves to tree trunks 70 feet in the air in order to prevent the building of the new road.

“They were different times,” Clare, who prefers to not to have her surname published, tells me. “We didn’t have the Criminal Justice Act or the Terrorism Act. So if we did digger diving,” she says of the tactic of hijacking, climbing or sitting on diggers and bulldozers to prevent them being used, “we wouldn’t be arrested for it.” Clare has just returned from a weekend of shamanic practitioner training and joins me and Hooper round the dining table.

“Yeah, I remember those times, they were great!” Hooper says, laughing. “Digger diving was brilliant. It was like a game of Bulldog,” he says of the old-school game that involves people trying to reach one end of a field or playground without being tagged by a lone “bulldog”.

“We used to just come out the woods and run at them! We’d try and get the diggers off them. They’d try and drag you out and you’d make yourself go limp so that other people could get in.”

The couple met at the Nine Ladies camp; a decade-long protest that eventually blocked any quarrying around the Nine Ladies Stone Circle in the Peak District. They lived there for two years, fell in love and moved to Tipi Valley when Clare became pregnant.

“To be honest, I thought this place was a bit nuts,” Hooper remembers. “Living in tipis in Wales? That’s mad! But the more we visited the more we were like, actually, it’s quite nice here.”

Although he doesn’t chain himself to trees or hide in tunnels anymore, Hooper is involved with his local Extinction Rebellion group. He was arrested in 2019 after attaching himself to a concrete block in protest against a fuel refinery in Pembrokeshire. In court he pleaded guilty to wilful obstruction of the highway.

“For me, it’s all about the target,” he says, his old passions afire again. “You know, trying to stop a refinery or a coal [development]. Actually having a target that you’re trying to do a direct action on, or put yourself in the way of something.”

I ask if he sees the influence that he, and the groups he was part of, have had on XR.

“It’s hard to say. Everything affects everything. We were probably influenced by Greenham Common,” he says, referring to the landmark women’s protest camp against nuclear weapons being stored at RAF Greenham in Berkshire, which lasted from 1981 to 2000. “[And by] the Suffragettes and everything that had gone before. There is an overlap. A lot of the core people in XR are people from the road protest movement. So there’s obviously overlap. But how do you quantify our influence? I don’t know how I could. It’s a progression.“

Although supportive and very much a part of XR, he does criticise some of their tactics, in particular the London rush-hour protest that took place on the top of a Canning Town tube train last October.

“I was like: why? It’s a subway. I didn’t mind the danger element. We were going to do it once. We were going to climb on top of the Docklands Light Railway to stop people getting to an arms fair. But with this one I was thinking: why are we trying to stop a really good thing – the Underground?”

There have, however, been some eco-victories straight out of the ’90s activism playbook. Earlier this year the protest camp “Grow Heathrow”, alongside other direct action, managed to block the building of the airport’s third runway. Hooper applauds that victory but also remains focused on the bigger battle.

“The main thing is that capitalism just isn’t good for the environment, and never will be. The overconsumption of things, making shite to sell us all the time, growth… We need to say: ‘No, we don’t need growth all the time.’”

As a father and someone who has been fighting the good fight since he was a teenager, I wonder what Hooper thinks about Greta Thunberg, mass school walk-outs and the wave of youth-led activism that was gaining increasing momentum before coronavirus halted everything.

“I think that it’s powerful. It’s just amazing,” he replies. “But I worry about Greta Thunberg, for herself. I’m not entirely sure that celebrity thing is going to be good for her. It’s obviously doing some good at the moment, though, but it leaves her open for people…” He tails off, but he clearly knows of what he speaks. “She is just so scrutinised. And when you build someone up it’s easy to knock them down.”

As his children stop stirring in their beds next-door and our wine glasses stand empty, I realise we’re now in the small hours. Our conversation has journeyed through decades, plotting the course of the activism, relationships and experiences that have made Dan Hooper the person he is today. But enough of the past. What are his thoughts about the future?

“I hope that we stop climate change and end capitalism,” he responds emphatically. “Things have got to change. A peaceful revolution – it feels like that can happen. I think things will change. Because they have to.”

We call it a night and I lay down on a makeshift bed he’s made for me in the yurt. With the wind and water outside as my lullaby, I close my eyes and think about the activist formerly known as Swampy’s peaceful revolution. I try to imagine what it will look like when it arrives.