Three artists reimagine a modern masterpiece with Bimba Y Lola

Grace Sinnott, Claire Barrow and Cato paid a visit to The National Gallery to see one of Georges Seurat’s seminal works. This is how they responded.

In partnership with Bimba Y Lola

Words: Ella Slater

Photography: Caitlin Ricaud

Georges Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières (1884) is huge and commanding – a centrepiece in The National Gallery’s collection that many recognise without even knowing why. But it wasn’t always so renowned.

Finished by a 24-year-old Seurat, the work didn’t immediately land. Its viewers were unsure of how to respond to a scene foregrounding working-class people and the burgeoning industrialisation of Greater Paris – as depicted in the factories and plumes of smoke overlooking the figures.

Still, almost a century and a half later, Bathers… continues to capture the imagination of contemporary artists, as well as flocking tourists, students and day-trippers.

To chime with Bimba Y Lola and The National Gallery’s capsule collection – soft, summery staples printed with the pointillist classic – we sent artists Grace Sinnott, Claire Barrow and Cato down to the museum to see Seurat’s work in person.

Riffing on its quiet radicality and themes – leisure, class and environment – each artist has applied their own unique medium to reimagine the appeal and significance of Bathers… today. We quizzed each of them on their initial response, process and end result.

Grace Sinnott

Grace Sinnott is a Manchester-born, Northeast London-based makeup artist with an experimental approach to beauty. To start with, she thought her career would be largely focused on special FX for films and TV, but eventually, she found her feet in fashion, going on to work with brands such as Vivienne Westwood, Mugler and Marc Jacobs, as well as musicians including FKA Twigs and Rosalía. Her work in a few words? Sexy, futuristic and otherworldly.

In response to Bathers… Grace has created a full upper-body makeup look, taking cues from her own local Asnières-sur-Seine. Her resulting work incorporates various aspects of Seurat’s technique, such as visible textured brushstrokes and a pastel palette.

Grace Sinnott stands before Bathers at Asnières (1884)

Had you seen the painting before?

I had, yes, but not in real life.

What did you find interesting about it?

I wasn’t expecting it to be so big, and I also wasn’t expecting it to be so textural in real life – you can really see all the brush strokes.

Did you research it further?

I did. I based my piece on a photograph, actually, of my family at Easter in a place called Lymm just outside of Manchester. When I was reading about the piece, I thought this was sort of a northern equivalent to me.

Given that you normally work within the realms of fashion and beauty, how did you find it responding to a 19th-century work?

I really enjoyed it. I didn’t take my inspiration literally. I think that’s the thing – you can push things as abstract and surreal as you want. There aren’t any rules.

What tools, effects and processes did you apply for this?

I used face paints for the base to get the gradient effect and, afterwards, I went over with thicker paint to create the more textured parts.

What do you like most about your creation?

The dog is actually my sister’s dog, Wilson! He’s dead cute.

Claire Barrow

Claire Barrow is a multi-disciplinary visual artist and fashion designer born in Teesside, North Yorkshire, now based in East London. Graduating from her BA in fashion design at Westminster University in 2012, she then made her debut at London Fashion Week as part of the fashion incubator programme, Fashion East. Eventually, Claire moved more towards art, making this her core creative outlet.

Nowadays, she exhibits her art regularly while also producing occasional fashion collections under her Xtreme Sports line. Her work engages with alternative pop-cultural realities, the kitsch, deconstruction and commodification, often drawing on the uncanny aspects of internet culture. Her materials of choice? Everything from broken mirrors and spray paint to gems and rubber bands.

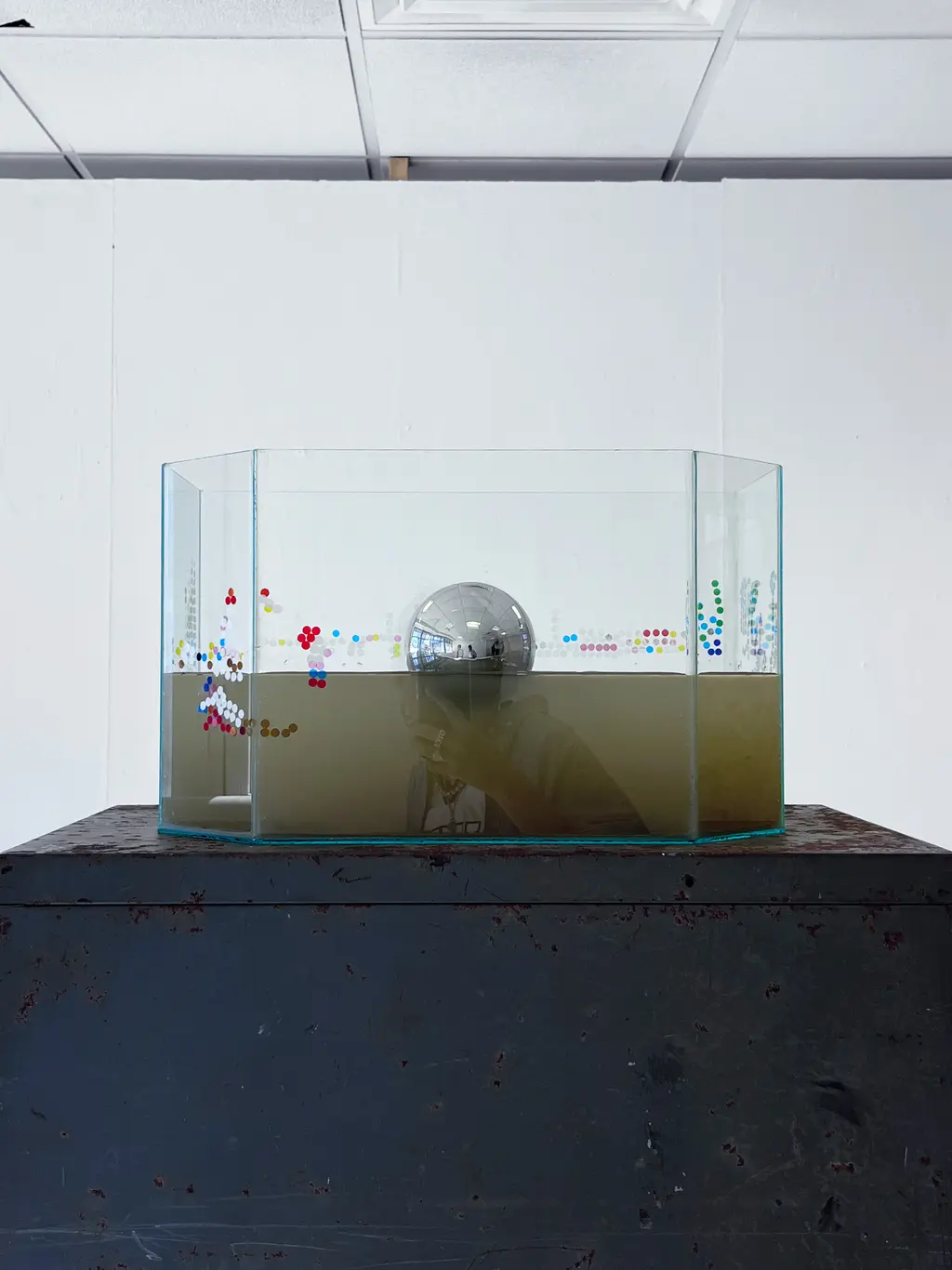

For this project, Barrow has created a sculptural work incorporating her local surroundings and immersive research practice. Featuring water from the River Thames and a chrome sphere inspired by the Barbican’s ponds, the work plays with Seurat’s use of colour, light and the reflective surface of the water in Bathers…

Claire Barrow stands before Bathers at Asnières (1884)

Had you seen the painting before?

When I was very young, my grandma Pat had a biscuit tin with either Bathers… or A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884) printed on it.

What did you find interesting about seeing the work again?

Discovering that Seurat was intentionally throwing shade at the looseness of the Impressionists changed my reading. He wasn’t romanticising leisure – he was making something cooler, more analytical. He takes this archetypal bourgeois subject, bathers by the river, and elevates working-class figures into a kind of modern myth. They become almost architectural, paired with the industrial environment that’s creeping into the background. The way their bodies interact with light, glowing auras emanating from them, gives them life.

What sort of narrative did it have for you?

I imagine the air is thick with factory smoke and heat, and the sun glaring off the water is brightening the polluted atmosphere around them. It’s easy to imagine [the people in Bathers…] looking out at the scene painted [in La Grand Jatte], which shows the upper class on the other side of the shore.

Did you research Bathers… after seeing it in the museum?

I read into Seurat’s influences and Michel Eugène Chevreul’s colour theory, and I did some studies to understand how Seurat approached light and form. I also spent a few lunchtimes lounging beside bodies of water in the city to feel some element of what the artist might have felt.

What does your response symbolise or represent in your view?

I wanted to work with the themes of the original painting, like class, work, industrialisation and the need to find quiet moments in the city. These are just as relevant to us now as they were then.

Cato

Born in Brighton and now based in London, the multimedia artist and musician uses airbrush and acrylic to create collage portraits that explore identity and community, often referencing jazz.

His scenes foreground the motion and gestures of bodies in everyday life: figures play dominoes, pass each other on the street or pray in domestic settings. While drawing on recognisable influences such as figurative painter Kerry James Marshall, late Malian photographer Malik Sidibé and digital artist Frank Dorrey, Cato’s work is exceptionally personal, and most of his references derive from imagery of characters near his studio in Peckham.

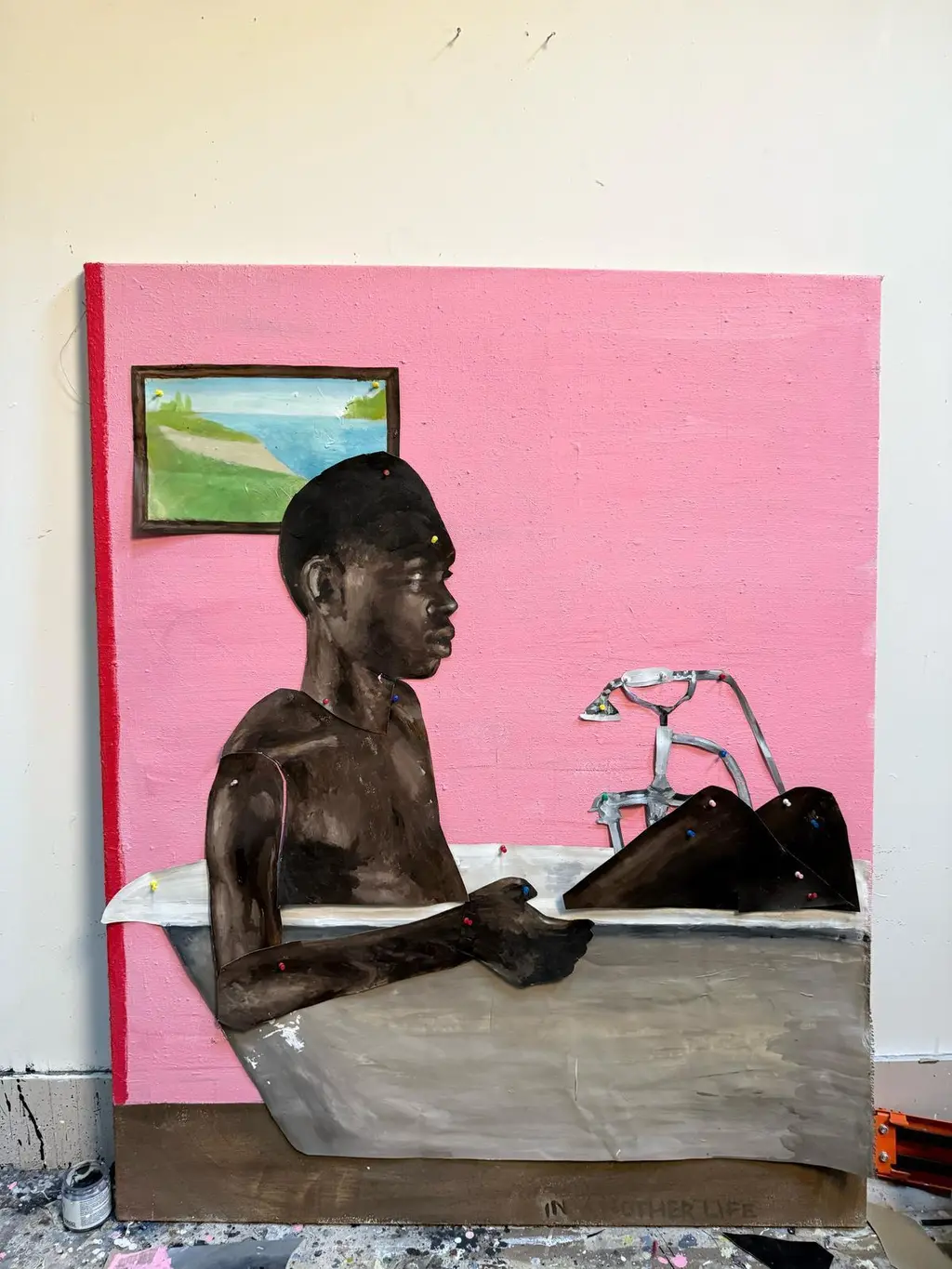

In response to Bathers…, Cato has painted a scene of introspection – “someone at peace, lost in their thoughts” – using a photograph from his archive. Elements of the original environment in Seurat’s masterpiece are incorporated into Cato’s subtle background detail.

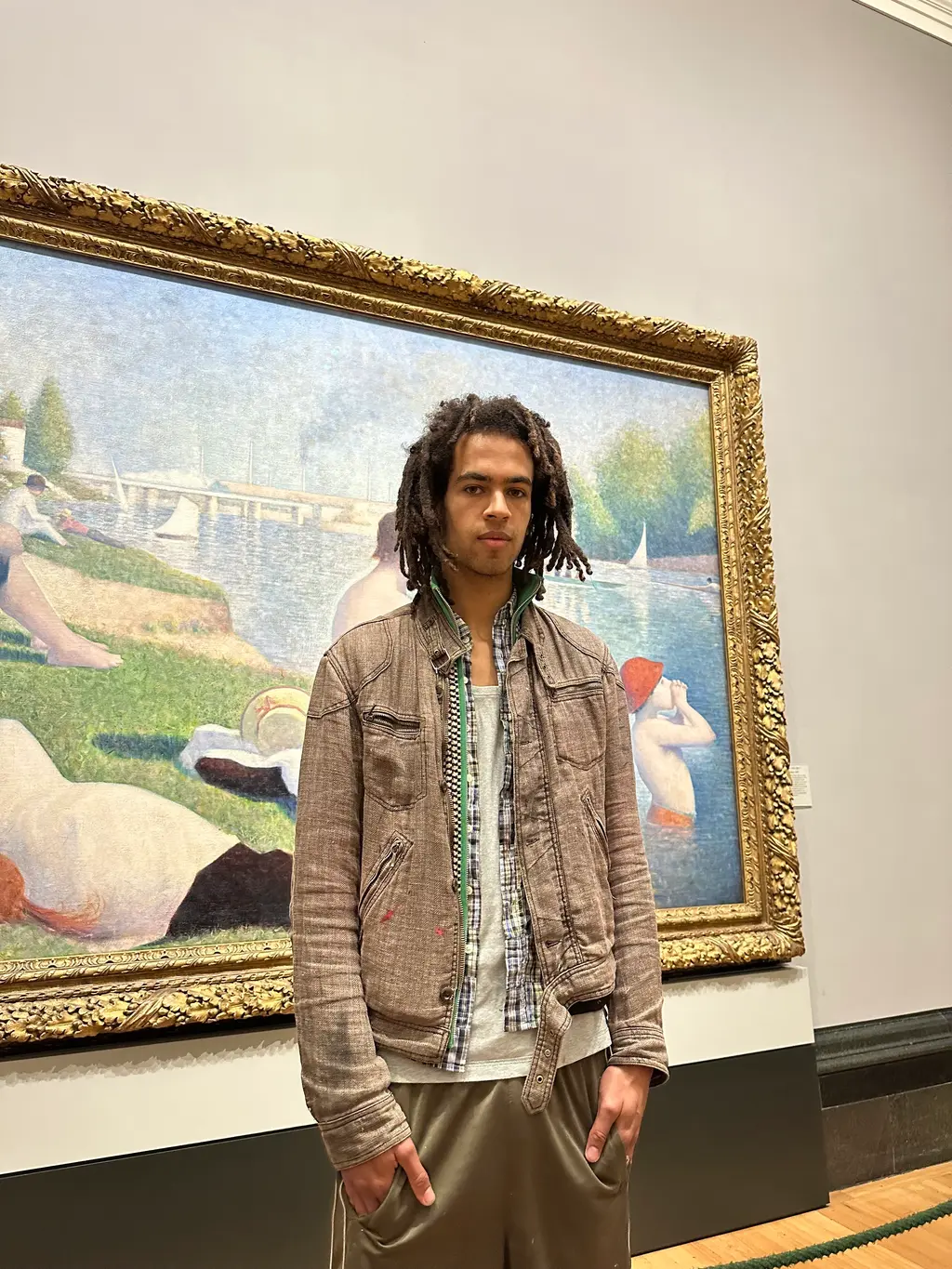

Cato stands before Bathers at Asnières (1884)

Had you seen the painting before?

Yes, I think I had.

What did you find interesting about the Bathers…?

I suppose the technical skill of the pointillism, the mood and the composition stick out to me.

What sort of narrative did it evoke for you?

It has a minimal, atmospheric narrative to me. It suggests the internal thoughts of the characters.

Did you research the work after seeing it or just let it carry your imagination?

I knew that Seurat was young when he finished it. [The work was painted between 1883 and 1884.] I tend to go from how a painting looks more so than the story – unless the story is famous.

What was it like to apply your collaged, cut-out approach to this particular project?

I tried to use a slightly different approach. I used only a paintbrush instead of using airbrush as I normally would. The body language of the characters was the main thing I was looking at.

What does your resulting work represent for you?

It represents a moment of reflection – I guess isolation and pensiveness.