The trans film programmers dolling up British cinema

Through screenings that unearth cinema's forgotten trans women, queer film societies TGirlsOnFilm and Funeral Parade are giving trans moviegoers a place to come together while shining a light on the thorny history of exploitation cinema.

Culture

Words: Patrick Sproull

There’s an early sequence in Let Me Die a Woman, Doris Wishman’s 1978 trans exploitation film, that is oddly reminiscent of Psycho.

A woman begins to undress for a shower, the camera parsing over her body as she slowly strips, a foreboding Bernard Herrmann-style score soundtracking her movements. Something is about to happen. She removes her underwear and – oh my goodness! – she has a penis.

The score swells hysterically, violins screeching as the woman, Ann Zordi, casually washes herself. Nothing really happens beyond Zordi lathering on Head & Shoulders, but Wishman’s film expects you to view this as some kind of violent act, a scandalous, jaw-dropping spectacle. To an audience of predominantly trans femmes who recently watched the film at the Prince Charles Cinema in London, it was comedy gold.

Coordinated by film programmers Jaye Hudson of TGirlsonFilm and Sarah Cleary of Funeral Parade, the screening of Let Me Die a Woman was part of their recent series of trans exploitation cinema at the Prince Charles. The pair met late last year when they participated in a BFI panel on transness in horror and quickly bonded over their shared appreciation for Ed Wood’s Glen or Glenda, a once-reviled film later appreciated for its timelessly pro-trans outlook.

“Ed Wood identified as a crossdresser in his lifetime,” Cleary, who works as an usherette at the Prince Charles, says. “There is the whole conversation around ‘transing the dead’ but it is safe to say that Ed Wood was a gender non-conforming person.”

“This is our history. It’s not perfect but it’s ours to rediscover and grapple with and come to our own conclusions with”

SARAH CLEARY

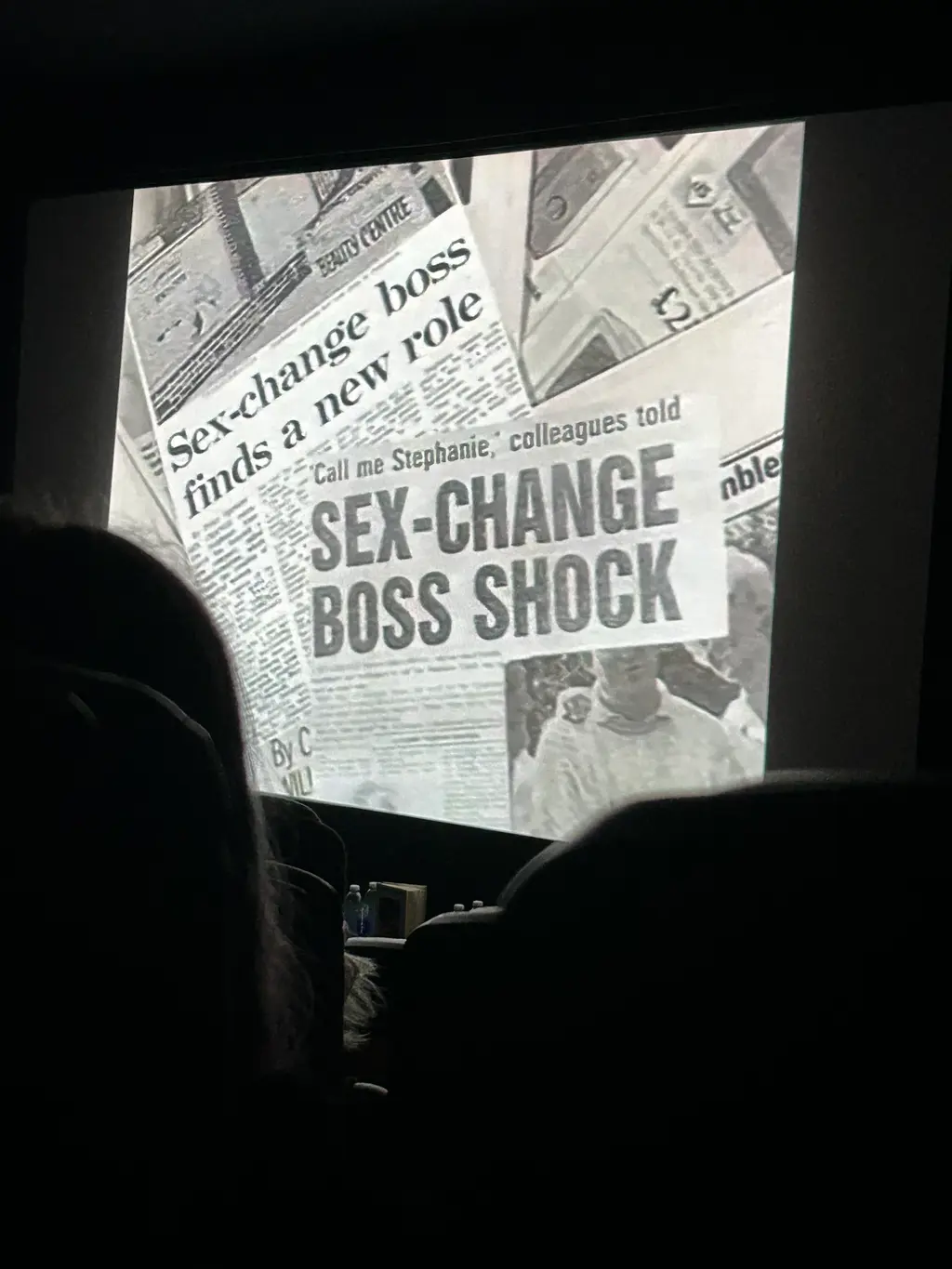

Cleary and Hudson decided to parlay their interest into hosting an 80th anniversary screening for Glen or Glenda in May this year. By this point they had also both started their own respective screening programs, TGirlsonFilm and Funeral Parade, dedicated to sharing cinema’s forgotten depictions of queer people throughout history. But after the success of the Glen or Glenda screening, they decided to pool their resources and establish a shared strand of events. Trans-X-Ploitation, which continued monthly at the Prince Charles, has shown other trans-themed dramas like She-Man, as well as documentaries such as Let Me Die a Woman, and British trans filmmaker Kristiene Clarke’s Sex Change: Shock! Horror! Probe!

“There was a sense between us that if we don’t do it, no one else will,” Cleary says. “I think Jaye and I both share a belief that this is our history. It’s not perfect but it’s ours to rediscover and grapple with and come to our own conclusions with.”

As two of the capital’s only trans film programmers, there was a desire to educate not only well-meaning cis audiences but also moviegoing dolls. This means that every screening starts with a short introductory talk, explaining the film’s context. In August, the pair were even able to get filmmaker and academic Kristiene Clarke and actor and cabaret legend Adèle Anderson to take part in a Q&A.

“I hope that TGirlsonFilm can be a small part of helping trans people be aware of their elders like Kris,” Hudson says. In particular, she’s keen for TGirlsonFilm to elevate British working class trans history, which is seldom documented. “In the British film industry, a lot of people’s references to trans history are related to American ideas of transness. It’s like: babes, you’re from Reading, your lineage is probably April Ashley or one of those women who owned a crossdressing shop, not Marsha P. Johnson.”

Giving a uniquely theatrical, uniquely trans experience was also important for Hudson, who’s an actor and “popcorn girl” at a London cinema.

“Doing introductions before the screenings, I didn’t want them to be bound by academic rule,” she says. Indeed, while there’s an educational core to TGirlsonFilm, that makes it sound drier than it is. “TGirlsonFilm is more of a local historian feel – just a girlie with a hobby who wants to share important information that wants to be eradicated but can be found through internet sleuthing.”

In an incredible reaction against stale film industry introductions, Hudson and Cleary force-femmed a seemingly unwitting guy at their screening of She-Man. The 1967 Bob Clark film is about a soldier who is blackmailed into taking estrogen and donning lingerie, and that’s exactly what they did to an audience plant. Hudson faked getting angry at him for being on his phone during her introduction (“I faked it so well that people clapped for me!”) before punishing him by dragging him on stage and making him wear a maid’s outfit she copped on eBay.

Their reason for doing this? “Um, it’s just fun,” says Hudson. “We wanted to keep building our theatricality.” This is a practice we can only hope the BFI adopts.

“I’ve been doing film criticism for about 10 years and you’re often the only trans person, let alone trans woman, in the room”

CATHY BRENNAN, FILM CRITIC

But TGirlsonFilm and Funeral Parade’s programming isn’t only about film, fun and theatrics. They’re also giving moviegoing trans women a place to come together.

“I’ve been doing film criticism for about 10 years and, being a film writer in UK film spaces, you’re often the only trans person, let alone trans woman, in the room,” says critic Cathy Brennan, who’s attended every screening. “That can be quite alienating, especially if you’re there with people in the media who represent publications that do not have trans people’s interests at heart.”

Brennan recounts a recent instance when, after a TGirls On Film x Funeral Parade screening while surrounded by other attendees, she saw two cis people awkwardly waiting for another film. “They just saw a bunch of us trannies swarmed outside the Prince Charles Cinema and they looked perturbed. I was like: wow, this is a small taste of what it’s like to be around [cis people]. I think it’s very valuable to be able to watch films like this with your people.”

Still, for some trans people, exploitation cinema centred on them can be a complicated and thorny subgenre.

“A lot of these films are quite tough sits,” acknowledges Cleary. “They’re filled with bigoted ideas and language. [So] we wanted to, with these screenings, provide a context for these films, because a lot of trans people might be curious about what there was pre-Orange is the New Black, but be anxious about what they’re going to see.”

Hudson and Cleary were also eager to cater to a majority trans audience. They marketed the screenings with an eye to curious trans people, making sure they were aware that TGirlsonFilm and Funeral Parade were there to provide necessary context. “We wanted to create a safe space, for a lack of a better term,” says Cleary. “We felt we could do something that we hadn’t seen anywhere else.”

In July, Hudson organised a sold-out midnight screening at the Rio Cinema in East London, of the summer’s great doll movie, Barbie, in which her fellow dolls could attend for free. “It was really special,” she says. “Having a majority trans femme audience felt so radical.” The lack of an entrance fee, though, wasn’t a gimmick – Hudson is acutely aware of the straitened circumstances of trans women in Britain in 2023. “Going forward, it’s something I’ll be thinking about because these big institutions can only get a certain type of trans woman in to watch a film [when] tickets are £15 to £20.”

Everyone involved is aware that these films aren’t all paragons of cinema. More important is the rich value to be had in viewing them in the curated circumstances TGirlsonFilm and Funeral Parade have enabled.

“Exploitation cinema falls under the broader umbrella of camp, of being able to appreciate the intention and the enthusiasm and allowing it to be bad,” says filmmaker Tristan Alice Nieto, who’s also attended every screening. “They subvert that traditional critical eye of ‘is this good by any pure, objective metric?’, which clearly doesn’t exist. I think the fact you can enjoy these films proves that.”

While deeply antiquated language around trans people is used in these films, there’s also an inherent curiosity about transness, not to mention an awareness, which contrasts starkly with the frothy-mouthed bigotry of Britain today.

As Sarah Cleary points out: “At one point in Let Me Die a Woman, Dr Leo Wollman, a surgeon who served as its scientific advisor, says ‘transsexuals are the most oppressed minority group’ – which is a pretty incredible statement to have in a film from 1977.”

It’s a damning indictment of the current state of queer cinema that schlocky exploitation films from 50 years ago can offer more for trans people than today’s more mainstream fare. And credit is due to Cleary and Hudson for unearthing a corner of trans history in such a thoughtful, lively way. Sure, it’s a flawed, complicated, difficult, funny history. But it’s history all the same.

Funeral Parade continues with a screening of Kamikaze Hearts at the Prince Charles on 14 November, while TGirlsonFilm returns early next year with a zine and more screenings. Force-feminisation not guaranteed.