Wolfgang Tillmans and Scott King: “Looking at what keeps society together is what’s needed”

Scott King / Wolfgang Tillmans, 48 European Election Posters, 2024

Three decades after first meeting at i-D, the creative duo have reunited for a series of downloadable designs to help get young people to polling stations ahead of the European Parliament elections.

Culture

Words: Tiffany Lai

When German artist Wolfgang Tillmans first met English graphic designer Scott King in 1993 the two did not get off to a good start. Both had just started at i‑D magazine and Scott, keen to make a good impression, decided to offer up an experimental layout by cutting up Wolfgang’s photos in an “anarchist” style. Wolfgang wasn’t impressed. He stormed into the office and demanded to know: “Who’s done this to my pictures?!” Scott kept his paper scalpel behind his back.

Despite that shaky start, the two quickly moved on and a 31-year friendship began. In that time, Wolfgang went on to become a Turner Prize-winning photographer, who rose to prominence in the ’90s for his immersive images of the LGBTQ+ club scene and later founded Between Bridges in 2017, a non-profit organisation dedicated to promoting the advancement of democracy. Scott, on the other hand, became the artistic director of i‑D and a lecturer at University of Arts London.

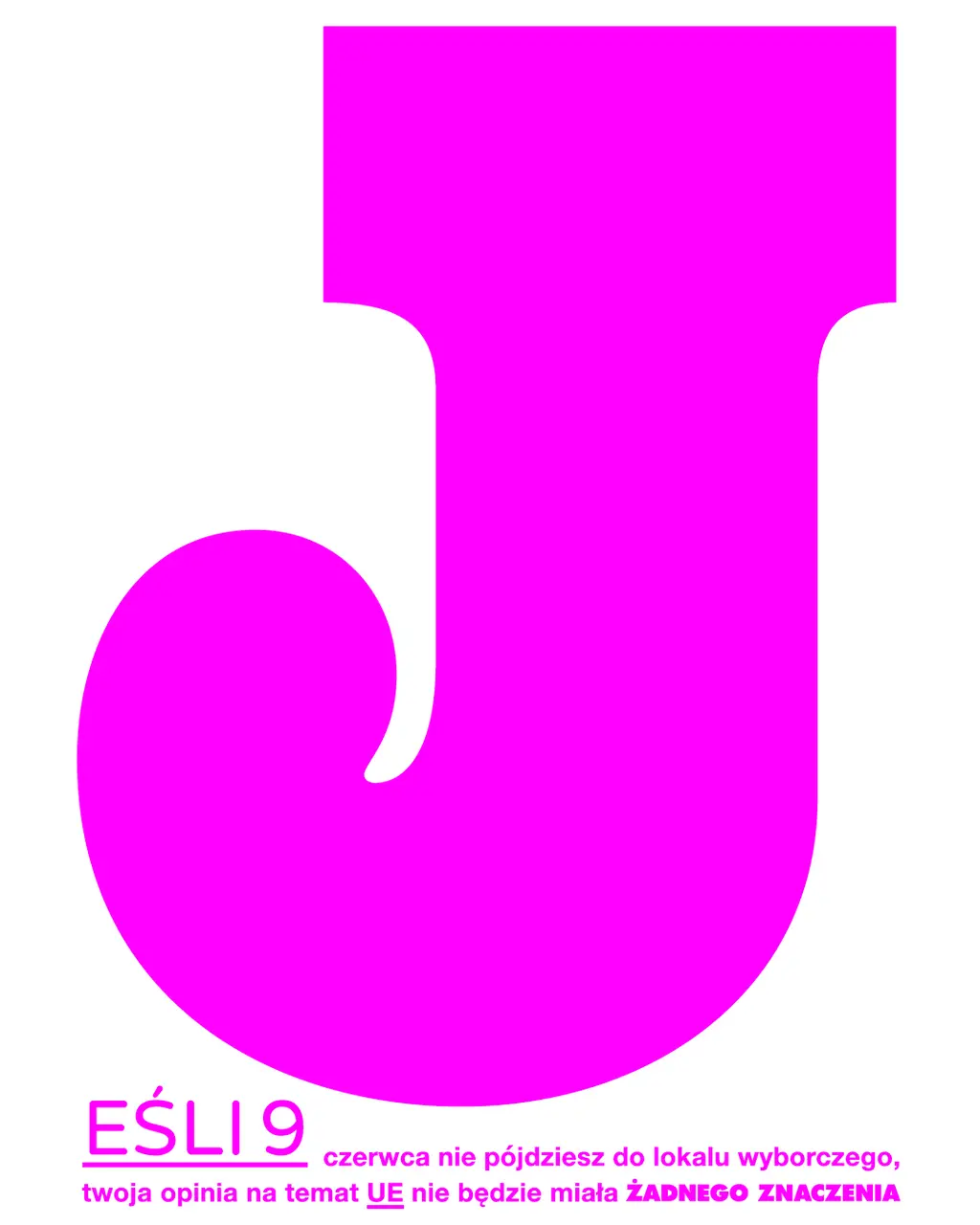

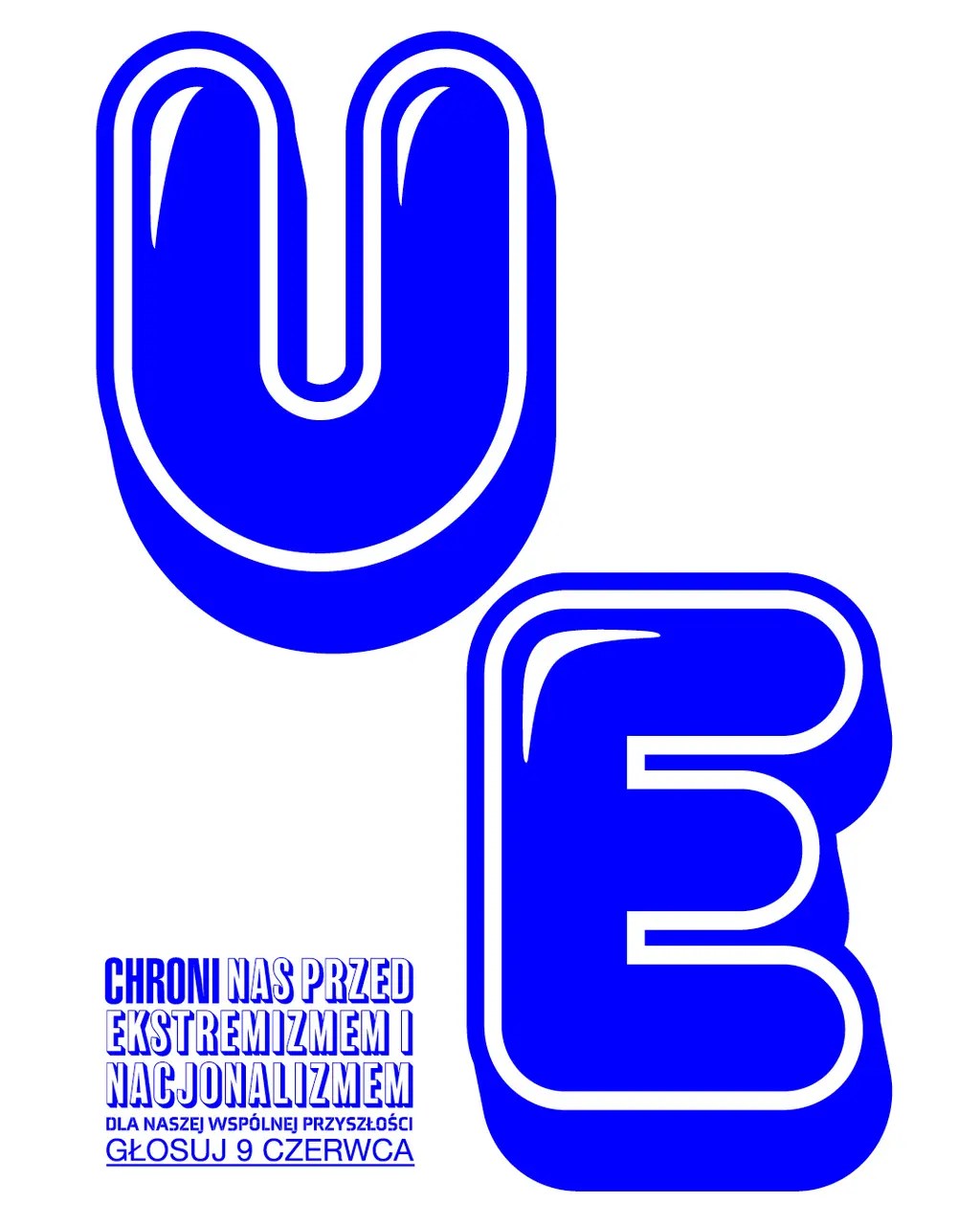

Wanting to keep their friendship intact, Wolfgang and Scott have been reluctant to work together on a design project since their magazine days. But this year, they’ve taken the leap and decided to collaborate on a series of playful designs for the Vote Together project, an offshoot of Between Bridges that encourages everyone to get down to their local polling stations. “They’re a beautiful image of the polyphony of democracy,” says Wolfgang of Scott’s designs for the campaign. Free to download and print on posters and T‑shirts, the aim is to get as many young people as possible in voting booths ahead of the European elections this week.

Franz Rogwoski by Wolfgang Tillmans, Berlin, Germany, 2024

Wolfgang, you’ve previously designed posters for the anti-Brexit campaign in 2016, the German federal elections in 2017 and the EU elections of 2017. Why did you decide to hand over the design reins this year?

Wolfgang: Interestingly, this time I felt clearly that I didn’t want to lead on these posters and I really wanted an outside language after having done it in previous years. I even thought maybe I wouldn’t do the campaign this year. But times are even more precarious today, so I was just really open to laying the design in Scott’s hands.

Scott: I was very grateful because I consciously want to do more graphic design, and Wolfgang had said he wanted something very playful inspired by Allen Ruppersberg. Of course, I went off and did completely the wrong thing and thought he was going to sack me! These fonts would make most designers cry, but they were very attractive to me. I love rubbish stuff, and I felt with all these languages and font debris there was a kind of universality to it. Being made from all these disparate and unwanted elements, it all seemed to tie together.

W: By making this absurd move of giving one letter 90 per cent of the poster, it makes you go closer and spend time reading the sentence. That’s why I think they work. I find that so convincing and playful.

I’m interested in this concept of absurdity and playfulness, and the power it can hold…

W: Politics is obviously very serious, as is what’s at stake, but there is something sort of finger wagging about [saying] “you better go vote”. So this idea to approach something serious in a playful way was my positioning.

And in terms of absurdity, I think that’s something that connects mine and Scott’s practice. We use humour in our work and want things to look light-hearted, but it is actually coming from a place of serious intent. When I grew up, I was definitely still in a world where the serious was communicated in a serious way and what looked pop‑y and superficial was deemed superficial and pop‑y. But the postmodernism of the ’80s and the punk movement allowed people to mix and match these contradictory things to ultimately tell serious stories.

S: A love of pop and pop culture is one of our great bonds and that’s the language we grew up with – pop as a vehicle for something with content.

A stranger on a dancefloor can be your friend.

Wolfgang Tillmans

Why is the EU so important to you?

W: One of our posters reads “360 million Europeans voting together” and that alone is a beautiful picture. The EU was an initially peaceful project bringing over 20 nations together to cooperate after centuries of war. The idea of the nation state as a solid is not something that existed forever. It’s something that came about in the 20th century. So to me, even though it’s not perfect and has a lot of problems, it is a beautiful image – it’s twenty seven people working and living in one house and sharing the bills.

And what is its importance to you on a personal level?

W: I mean, what’s striking is that Europeans feel most European when they are on a different continent. When you’re in the United States, for example, and an Italian, a German and a Scottish person are in a group of 30 people, those three people would realise how similar they are in comparison to the Texans.

And when we worked at i‑D, the magazine was fascinated with promoting an idea of pan-European music… You remember our trip to Madrid, Scott?

S: Yeah, I remember – I was about 24 and had food poisoning! And it was so hot and I was sweating so much, it was like a bad acid trip. I went down to buy some deodorant at the chemists and when I got back upstairs I sprayed it and realised it was shaving foam. I thought I’d actually lost my mind!

But on a less trivial note, i‑D was very much interested in an internationalist idea, particularly with Matthew Collin, who was the editor at the time. It was also post acid house, so there was a general idea of love and cooperation in the air.

W: And the idea that strangers don’t automatically signify dangers or enemies. A stranger on a dancefloor can be your friend.

S: In fact, Wolfgang’s whole career again began with this feeling and documenting that world.

W: On the one hand, it was documenting something that felt utopian and like real life, but then on the other hand, it was the creation of utopian pictures that looked real – like the ones of Alex and Lutz sitting in the trees. They were coming from the same spirit of not being afraid of your own body and your own sexuality, as well as not being afraid of each other, and so I was inspired by this hope of a new post-Cold War era of cooperation and international exchange. I still believe in it and I think it is the best model that we have. But obviously one has to ask what went wrong in the last 30 years.

Peter Puklus by himself, Budapest, Hungary, 2024

The UK is now also very close to an election. What’s your sense of the general mood?

W: The UK does not have a two-party system, but it has a first past the post system. And so this complete black and white result makes it incredibly hard for nuanced expressions of political opinion, and this idea of choosing the lesser evil must be incredibly frustrating. But I hope that feeling of frustration never comes between people ultimately making a responsible choice. In 2016, everyone thought “of course no one will vote for Brexit”, so it’s important not to take a Labour victory for granted.

S: I actually remember in 2015 speaking to Wolfgang and he was determined that Brexit was a reality. I remember saying, “Don’t be ludicrous!” And he was absolutely right. Although I’m from Yorkshire, I live in this bubble in London and you become very unaware of what the reality for many people is and what poverty is. Brexit’s very complicated, but there were people who were voting against London in many ways, against this cosmopolitan elite. I think Wolfgang’s right, we shouldn’t presume anything at all because Brexit did happen.

What gave you that insight in 2015, Wolfgang?

W: It started when I moved to England in 1990 and saw the passionate and arrogant rejection of the European Union in the headlines of right-wing papers, I just understood that this was dead serious. And then later, in 2016, I felt so little passion on the remain side compared to the leave side, so I ended up in a position as a progressive artist campaigning for something that was seen as boring and mainstream. But looking at what keeps society together rather than apart is perhaps an even more radical and needed thought today.

Wolfgang, you talked about the struggle of making political activism cool amongst young people in 2016, where do you feel we stand in that struggle now?

W: The last eight years have definitely been a wake up call for more people to be interested in politics and society, but the problem is young people still don’t see parties as the place where change happens. The reality of our democracy is that typically only party members end up in parliament and decisions are made in parliament, in town halls and councils. It’s much easier to be involved in an NGO or a protest than taking that protest inside the town hall.

S: People see it as the business of adults, because of course politicians are always older than you. But when you get to Wolfgang and I’s age, politicians are suddenly the same age as you or younger. Most people think politics is the business of experts but that’s proven to be a mistake. These people are not experts at all.

What are your hopes for this campaign?

W: I can wholeheartedly say there are far-right nationalists and religious fundamentalists that are all fired up about this election, and they want to take the European Union apart from the inside. They know how powerful the European Parliament is and they know that the low voter turnout typically associated with these elections gives them a disproportionate percentage of seats for voters that want to turn back the clock. Those people will definitely go to the polls and I hope that this project will just change the dial a little bit. The concrete hope is that, like in 2019, over 50 per cent of the electorate will vote, giving the Parliament a strong mandate.