The femininomenonal ascent of Chappell Roan

Her hot-blooded anthems – not to mention that delicious braggy, draggy persona – have infected the pop world and turned Chappell Roan into its newest hometown hero. Now, with barely a second to take it all in, she’s staring into the abyss of superstardom.

Music

Words: Delia Cai

Photography: Sharna Osbourne

Styling: Danielle Emerson

Taken from the autumn 24 print issue of THE FACE. Get your copy here.

Yes, Chappell Roan has been talking to all the girls: Gaga, Charli, Sabrina, Lizzo, Katy. “I just got coffee with Lorde and Phoebe [Bridgers],” she says with a self-effacing grimace that indicates she knows how that sounds. “Tomorrow, I’m going over to see Lucy Dacus [of Bridgers’ side project boygenius].”

Everything – and by “everything”, we mean the femininomenonal ascent of Chappell to the summit of Pop Mountain, Summer ’24 – started in early spring, when the Missouri-born singer-songwriter began shooting up the mainstream spine of awareness via an opening slot on the North American leg of Olivia Rodrigo’s Guts tour.

As spring gave way to Pride and festival season, a storm of viral performances from Coachella,The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, MTV and NPR’s Tiny Desk online gig series flooded social media with clips of Chappell performing her now inescapable queer anthems, including Good Luck, Babe!, and her music quickly began scaling the global charts.

To put things into context: last September, she dropped her debut album, The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess, to little fanfare beyond her cult following. This August, it climbed to Number One on the UK Albums Chart – almost a full year after its original release.

At first, back in the spring, she didn’t understand why huge stars such as Gaga and Charli were suddenly checking in to see if she was OK. “I was like, ‘Mmm, this isn’t that big. Everyone’s so dramatic!’” she says. Now, Chappell recognises the pop girls’ protectiveness as a lifeline. “They were immediately, immediately supportive,” she says, smacking her palms together for emphasis. “Immediately.” Her voice grows taut, almost aggressive, from a rush of emotion before melting back into the quiet admission of an overwhelmed 26-year-old: “It’s been so amazing, because I’m very scared and confused.”

Chappell wears jacket COACH and shoes COURRÈGES

Chappell wears dress BATSHEVA

It’s now peak summer in Los Angeles. We’re speaking at Chappell’s FACE cover shoot in a sedate rented house in Beverly Hills. Here, everything is so high up you can only hear a faint rumble from the myth-making capital below, which is currently hidden under a thin watercolour wash of clouds. A pool in the garden glimmers green from a surrounding bed of finger-thick succulents, while palm trees flutter softly in the breeze. But Chappell barely gives it a second glance as she sits down to eat a yoghurt-with-chia-seeds breakfast thing, introducing herself to the shoot’s team by her given name, Kayleigh.

This is about as calm as it gets these days. We’re catching her in the midst of a breakneck headline tour, where the strength of a Chappell Roan billing has fans straining the capacity of not only each venue, but also every surrounding parking space, petrol station and city block within hearing range. Her performance at Chicago’s Lollapalooza (which had to be upgraded to a main stage slot originally booked for Kesha) is estimated to have drawn the festival’s biggest of all time. It’s like watching Lady Gaga coming up, the Chappellites proclaim. Wait, no. It’s like watching Madonna.

Her ascendance is part of an electrifying coalescence of a new kind of female pop archetype: one who is winkingly hedonistic, disdainfully unapologetic and completely assured with her sexuality (you might describe her as a bit of a Brat). In a matter of months, the super-graphic, ultra-modern pop star’s reach has become unavoidable, as an ever-growing rank of evangelists invoke her name with the breathlessness of exchanging news of salvation. It’s her music, obviously: equally tender, raunchy and effervescent; packed with lyrics primed for the karaoke booth and club night singalongs. Even if you’ve never intentionally listened to Good Luck, Babe! you probably already know its most famous line: “You’d have to stop the world just to stop the feeling”.

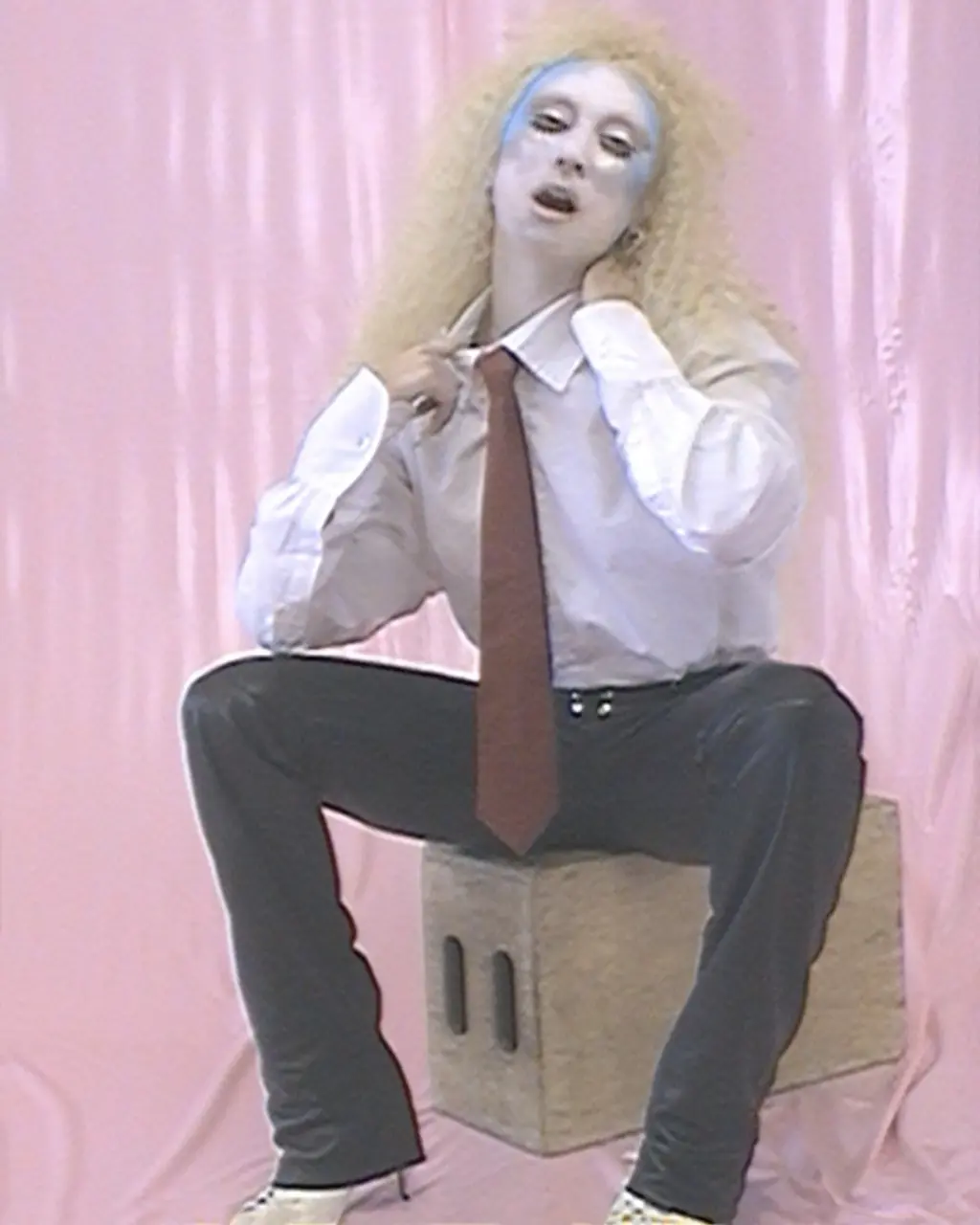

It’s also Chappell’s glorious drag queen persona – the powder-white clown face, the magnified brows, those metamorphic costumes, the time she performed as the Statue of Liberty – and that electric live performance energy. Not to mention the small-town-girl-makes-it-big and lesbian actualisation arcs crystallised into her lore.

They’re talking about her at queer parties and on radio stations and at farmers’ markets and inside the Harris-Walz campaign, which used her 2022 single Femininomenon for a Trump-baiting TikTok video and mimicked the design of her Midwest Princess camo trucker caps for official election merch. Her music is even being played at the straightest weddings you can imagine, where people have mastered the YMCA-like choreo to the cheerleader-esque Hot to Go!

The Great Roaning of ’24 has left those who haven’t paid enough attention so embarrassed they’re scream-crying the nonsensical accusation of “industry plant”. You kind of feel bad for them. Imagine missing out on this.

But what has the ascent felt like for her? Perched now in a windowless glam room, Chappell takes a sip from her Erewhon matcha latte (yes, she’s tried the Hailey Bieber smoothie: “And you know what? All you bitches think this is healthy, but this is just a milkshake!”). To say that she’s overwhelmed is an understatement; the fame monster doesn’t exactly wait for you to catch your breath. “No one understands that it truly falls all on you,” she says. “No one understands except other artists… Sabrina [Carpenter] even texted me: ‘Hey, I feel crazy. I know you feel crazy.’ So it’s, like, girlies leaning on each other.”

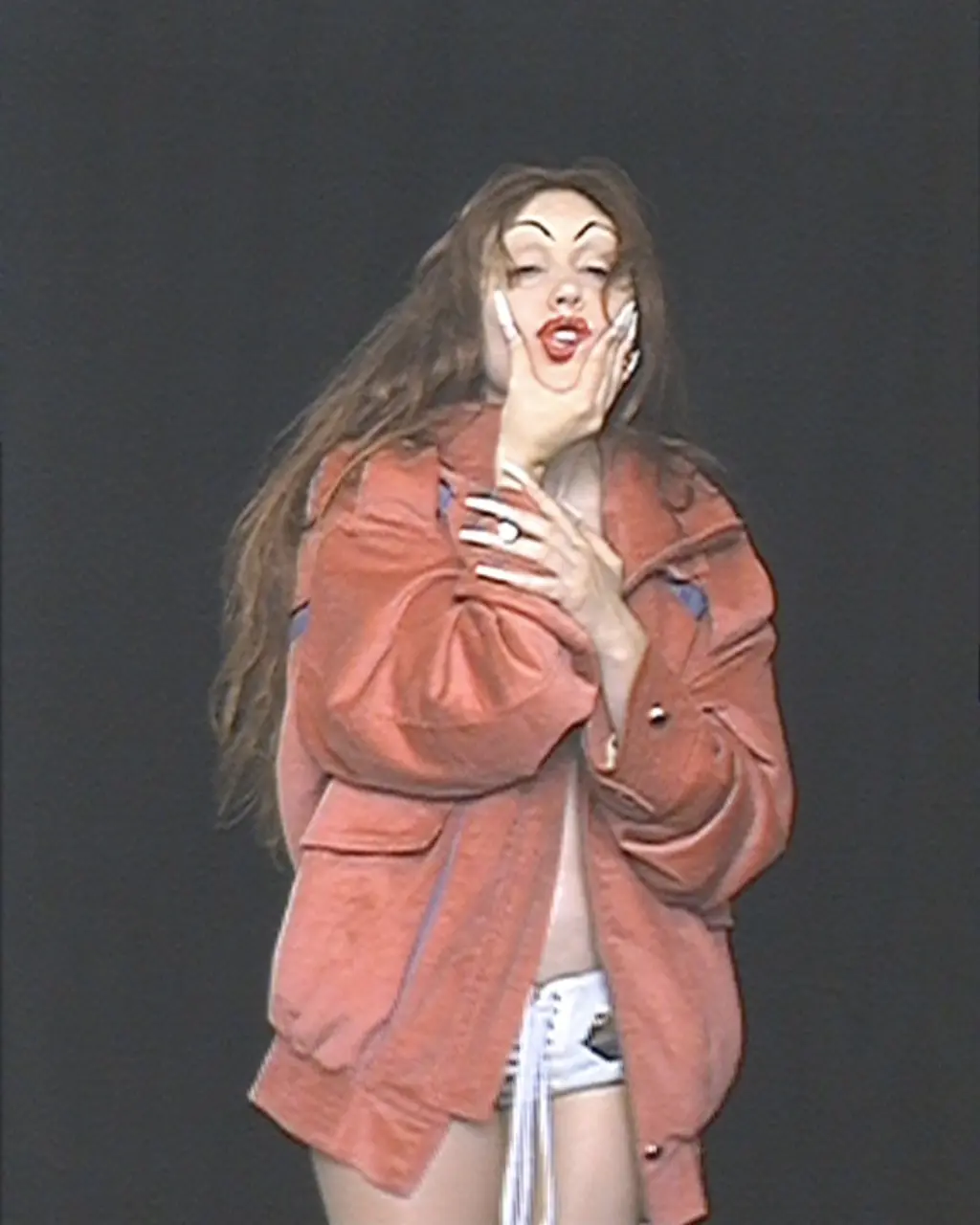

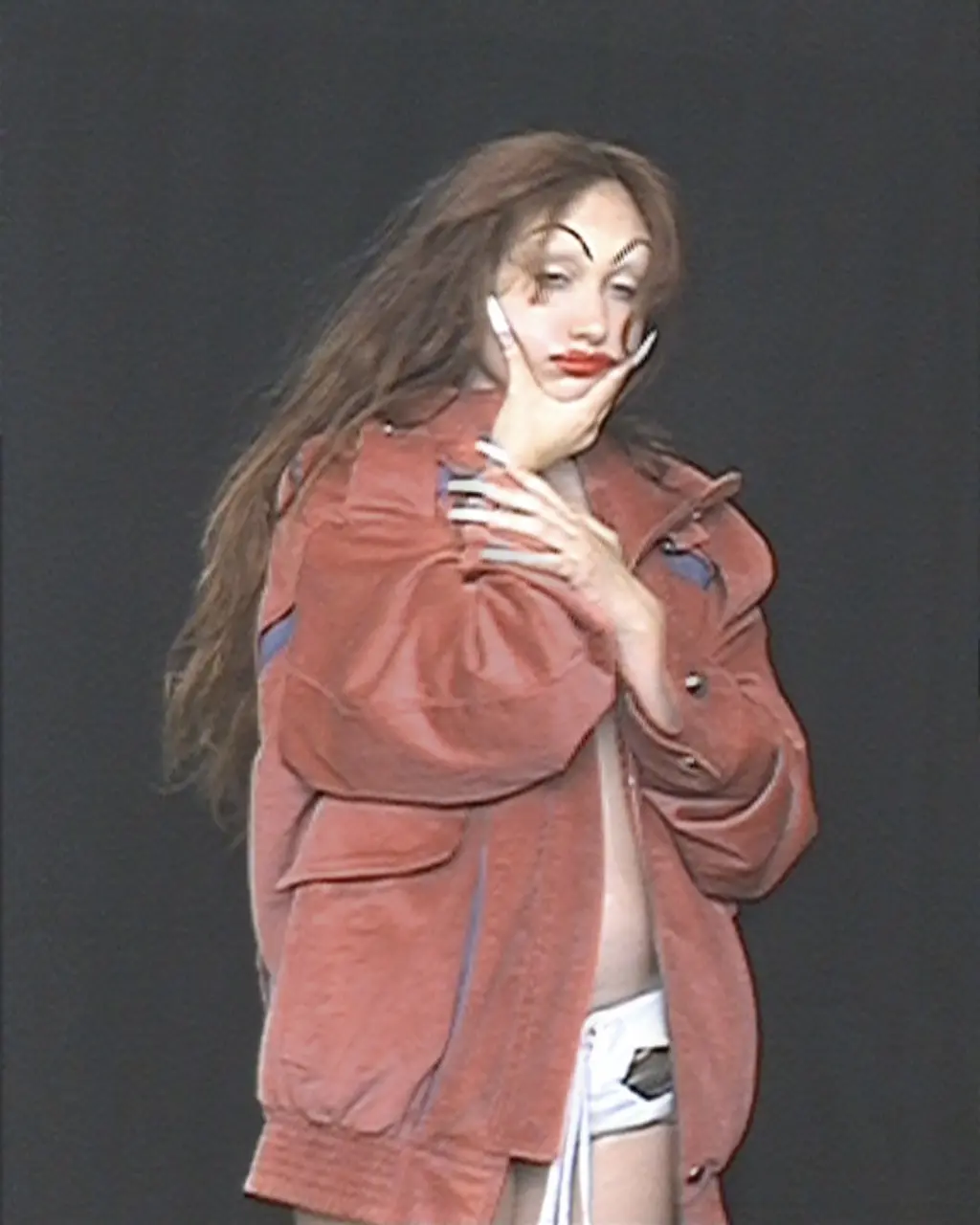

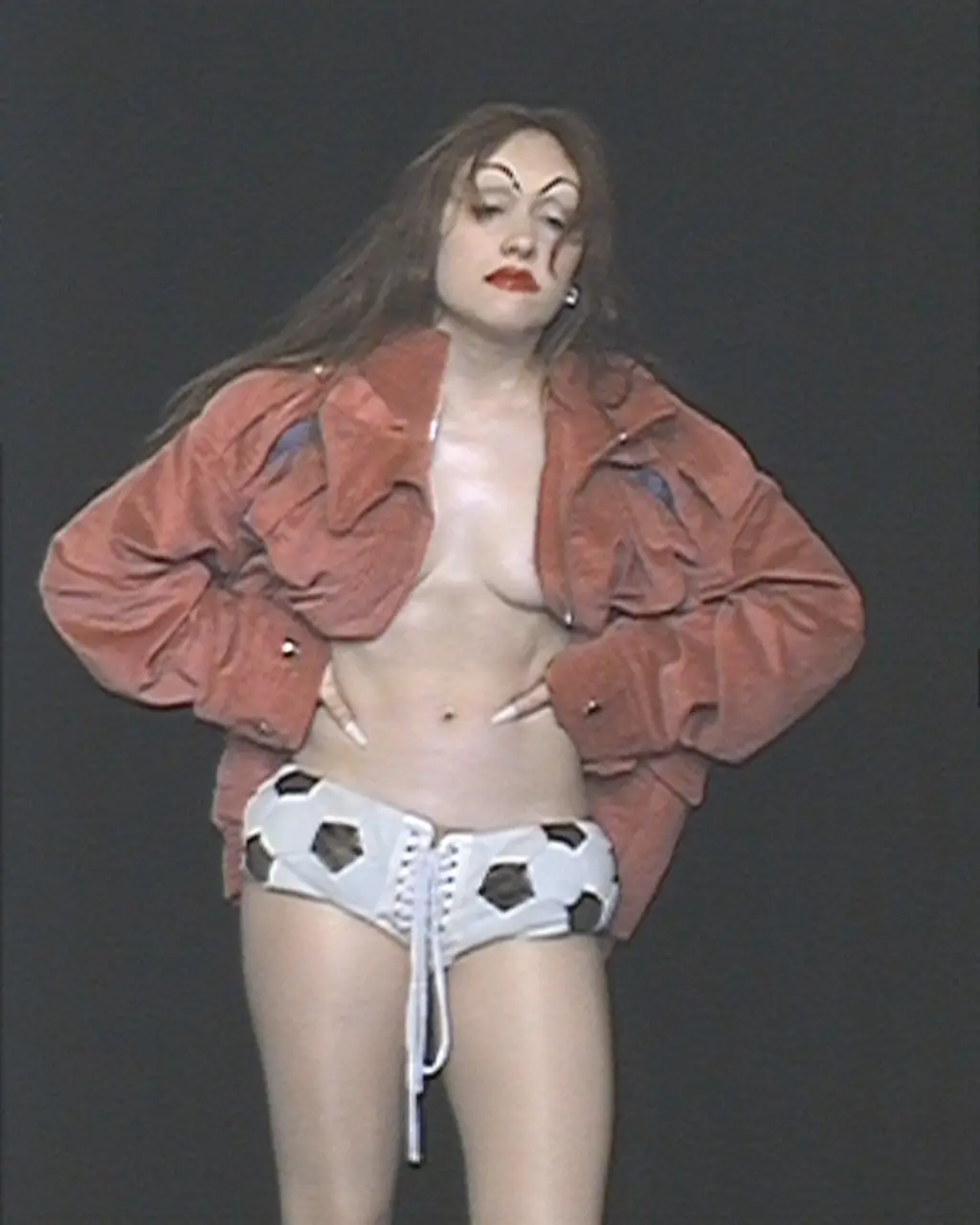

Chappell wears jacket KIKO KOSTADINOV and shorts ROCKSTARKING

Chappell wears jacket KIKO KOSTADINOV and shorts ROCKSTARKING

Chappell wears jacket KIKO KOSTADINOV and shorts ROCKSTARKING

It’s a long way from home. Born Kayleigh Rose Amstutz in the very Christian, very traditional city of Willard, Missouri (population: approx 6,500), she began writing songs after winning an eighth-grade talent show, carving her own path as the eldest of four kids in a decidedly non-musical family (her parents own a veterinary practice). Chappell’s early career followed a mostly conventional pipeline for any young talent with a capital‑V Voice, the kind that shimmers across your face, full and lush, like a peach begging for someone to sink their teeth in.

First, you take piano lessons, figure out you can sing and start posting covers on YouTube. Then, just into your teens, you start writing your own songs and maybe try out for America’s Got Talent, before signing with Atlantic Records at 17 and adopting a stage name (her late maternal grandfather Dennis Chappell’s favourite song was The Strawberry Roan by country and western star Marty Robbins). Finally, you beg your high school to let you graduate early so you can move to LA. Once there, Chappell quickly traded the moody, goth-Ophelia energy of her 2017 debut EP School Nights for sparklier explorations of love and life in the big city. Her first collaboration with co-writer and producer Dan Nigro (who produced both of Olivia Rodrigo’s albums) led to the jubilant anthem Pink Pony Club, which had the misfortune of being released in April 2020, just as the clock struck Covid.

After releasing two more singles, Love Me Anyway and California, Chappell was dropped by Atlantic and, within months, found herself back in her hometown, where she spent the summer working the drive-through at the nearby Springfield branch of Scooter’s Coffee (“The worst coffee in the world!” – her words, not theirs). She agonised over her options. Maybe this was as far as she could go and it was time to head to university, or New York or Nashville. Instead, Chappell gave herself a deadline: one more year in LA. She moved back that October and spent the majority of the months that followed juggling odd jobs and crying endlessly in bed. “I was just like, ‘You have to keep going. You have to give this a shot. What if it’s right around the corner?’”

This time, as an independent artist and with the help of Nigro, Chappell doubled down on the hyperfeminine exuberance whose potential she’d glimpsed in Pink Pony Club. The string of singles that followed – My Kink Is Karma, Femininomenon, Casual – showcased her obvious knack for lovelorn storytelling, while the creative direction of her music videos leaned into femme camp. In the Casual video, she played out a queer Little Mermaid-gone-wrong fairytale; in a promo for Femininomenon, she’s pictured on her dad’s tricked-out and bedazzled dirt bike wearing hot pink leathers and studded denim underwear. The vision!

And, like any digital-age twentysomething out of fucks to give, Chappell started posting on TikTok, where her talent and relatable agent-of-chaos energy found a perfect audience. In a video from 2022, she crooned unbothered to her guinea pig. In another from the same year, she plucked silicone bra inserts out of a tank top and declared: “No one is going to take me seriously whenever I release my serious songs because I burn that bridge with my FUCKING! TIKTOK!”

This work helped amass the earliest Chappellites. The labels soon came knocking, but she’d already inked a deal with Nigro’s imprint Amusement Records (a subsidiary of legacy label Island), which he set up specifically so that he could sign her. (“I was so in love with everything that we were doing,” Nigro told Billboard. “I just believe in [Chappell] so much that I was like: ‘Do I want this added stress in my life? Is it worth it? Yes.’”)

dress BATSHEVA

jacket COACH and shoes COURRÈGES

shirt, jockstrap and necklace ANDREAS KRONTHALER FOR VIVIENNE WESTWOOD and shoes MARC JACOBS

“I probably have one of the best deals ever in modern music because I was like: ‘Fuck you guys, give me what I want or I’m going to do this myself,’” she laughs. “Now I can be like: ‘Look at the numbers, bitch.’” Has this zigzagged road to success made her nervous? She’s already seen the bottom drop out once before, and pop music isn’t exactly a model of job security. But Chappell is resolute. “I had no money for many, many years, and it’s fine!” she says. “I’m just kind of like, bitch, I’ve been here the whole time! I got signed a year after Ultraviolence came out [in 2014]. That’s how long I’ve been here. That’s how many Lana Del Rey albums are in between!”

dress BATSHEVA and shoes HODAKOVA

dress BATSHEVA and shoes HODAKOVA

It will surprise you a zero amount how much Chappell loves playing dress-up. New York history was forever changed by the look for her Gov Ball festival set in June, where she performed as a spraypainted, ass-forward Lady Liberty. At the time of writing, Chicago is still quaking from her lucha libre get-up at Lollapalooza. On the FACE set in LA, she pads around stocking-footed, first wearing a strap-on harness belted over a flowy tunic, then a pair of witchy clogs and what can only be described as a hot-girl lace-up American football girdle.

In front of the camera, Chappell opens and closes herself like a butterfly, shifting from guarded protectiveness – arms twisted around her waist, palms crossed as if to block an incoming projectile – into total insouciance, squatting and splaying out her limbs like a giggling, sentient Troll doll. Using her hands, she stretches her mouth to toggle between sneers and silent screams. Less Cinderella, more wicked stepsister. “I’m not good at hot, but I am good at scary,” she says at one point, popping one of the puff-balls that have been stuck onto her cheekbones straight into her mouth.

dress BATSHEVA and shoes HODAKOVA

I’m curious about the performance persona of Chappell Roan – which she’s often described as her drag project – and whether it stems from any specific childhood inspiration. As anyone who’s attended sleepaway church camp worship night can attest to, the American Bible Belt has quite the theatrical tradition. But she minimises the early influence of her Christian upbringing and even modern drag culture as subjects of direct study. “I didn’t start watching Drag Race until last October! I was really confused about the ‘reading’. Like, that’s so mean!”

It is, then, difficult to extract a sense of what young Kayleigh was like and whether this streak for pageantry was in her all along. Wasn’t she at least the type of kid who put on cartwheel-inflected dances to Britney Spears in the family basement? Her whole face softens at the assumption. “I wish I was that girl,” she says. In reality, little Kayleigh was a “problem child”, constantly fighting, kicking holes in walls and going in and out of therapy.

Growing up, she felt isolated, not only within the rural Midwest but also her family and her own brain – she was finally diagnosed with bipolar II in 2022. “All I want in life is to feel like a good person, because I felt like such a bad person my whole life – the worst kid in the family, always so out of control and angry,” she says. “It’s been really hard to forgive, one, my parents for not knowing how to handle that correctly. And two, myself, for being like, dude, you were unmedicated, going through puberty and refused to believe you were anxious or depressed.”

The project of Chappell Roan, then, can be more wholly understood as a therapeutic experience, not only for fans who might have an idea of what those emotions feel like, but also for the artist’s younger self. “Now, I am the girl who does the Britney routine; I am the girl who plays dress-up. I’m making up for that time. When I realised that I should dedicate my career to honouring the childhood I never got, it got big quick.”

“Big” as in becoming a de-facto festival headliner in the US, touring through Europe this autumn and, hopefully, nabbing some music trophies. Nominations in multiple Grammy categories, including Best New Artist and Song of the Year, seem like a no-brainer. “My mom would love to go to the Grammys or the Brits,” she says. But Chappell is, at best, iffy on the whole awards thing. “I’m kind of hoping I don’t win, because then everyone will get off my ass: ‘See guys, we did it and we didn’t win, bye’! I won’t have to do this again!”

What’s more important to Chappell is the long game. “I feel ambitious about making this sustainable,” she says. “That’s my biggest goal right now. My brain is like: quit right now, take next year off.” Her mouth forms a small, tense line again. “This industry and artistry fucking thrive on mental illness, burnout, overworking yourself, overextending yourself, not sleeping. You get bigger the more unhealthy you are. Isn’t that so fucked up?” It’s a problem within the music industry, she notes, but also its attendant attention machines – TikTok, Instagram, the entire internet – which all feed on manic self-compulsion. “The ambition is: how do I not hate myself, my job, my life, and do this?” she says. “Because right now, it’s not working. I’m just scrambling to try to feel healthy.”

jacket COACH and shoes COURRÈGES

Shirt, dress and gloves MIU MIU and shoes COURRÈGES

dress BATSHEVA and shoes HODAKOVA

jacket COACH

Chappell wears jacket KIKO KOSTADINOV and shorts ROCKSTARKING

The Kayleigh side of her still craves the idyll of anonymity – off-hours, she’s been caught by fans practising somersaults in Central Park and racing shopping carts in Ikea. But such bursts of spontaneity are getting rarer. These days, she almost always has to wear a wig in public. She’s even had to let her therapist go, after realising they were no longer equipped to deal with her rapidly accelerating fame.

And it’s getting scary, actually. There are now paps, scalpers and obsessives who buy plane tickets just so they can wait at the gate for when she lands. For every unicorn of a young star with the power to command gigawatts of attention, there’s a seedy microeconomy sprouting around and glomming on.

Take, for example, a recent encounter at the airport. “I get out of the car, it’s 5.30 in the morning, and there’s two guys waiting with a bunch of posters and shit for me to sign,” Chappell says, her voice tightening again. “I know they’re not fans. I said no. I was like, ‘I don’t sign anything at the airport, I’m sorry.’ [One of them] follows me to the TSA line, starts yelling at me and everyone just turns and looks. He’s like: ‘You should really humble yourself. Do you know where you are right now? Don’t forget where you came from.’ I’m just like: ‘What the fuck is going on?’ I told myself, if this ever gets dangerous, I might quit. It’s dangerous now, and I’m still going. But that part is not what I signed up for.”

She takes a breath. “I feel like fame is just abusive. The vibe of this – stalking, talking shit online, [people who] won’t leave you alone, yelling at you in public – is the vibe of an abusive ex-husband. That’s what it feels like. I didn’t know it would feel this bad.” While crying in the bathroom in the airport, she texted Lorde for advice. “She sent me a list of things I should do [in that situation],” Chappell says. “Literally wrote down eight things she wished someone would have told her when she was going through it. And she went through fucking hell. She was a baby!”

dress BATSHEVA

dress BATSHEVA

shirt, trousers and tie LUDOVIC DE SAINT SERNIN and shoes MAISON ERNEST

dress COURRÈGES

dress COURRÈGES

dress BATSHEVA

jacket COACH

Listening to her talk, you can feel everything: the fury, the despair, the confusion, the resolve, the swirling depths of her personal storm. The resonance of Chappell Roan is not so much something to be understood simply from the music she makes or her aesthetic and stagecraft, but something you have to take in as a greater act of performance art. One where she dredges up the worst, most jagged edges of being a human who can feel angry, lost, jealous, vindictive, reckless, horny and scary-hot. Then she delights in it. She pairs it with dazzling synths, invites us in and turns the whole thing into an inclusive party, transmuting the project from she to we.

So, what does Chappell Roan need from us? If her success is to be understood as a collective movement, where fans feed off the music and the magnetism she’s able to dole out, despite the increasing crush of fame, what sustains her? What’s the one compliment that actually matters?

She peers out from behind the curtains of that unmistakable mane, having gone quiet again. “Everyone’s like, ‘Oh yeah, she’s really intense,’ which, whatever, fine,” she says. “But I don’t very often get: ‘Oh my God, you have such a good vibe.’ I think that just stems back to childhood, of [wanting] people to believe that I’m a good person and me believing it, too. So it means a lot when I hear that.” She thinks this over.

“I can’t read my DMs anymore, because I cry so much,” Chappell says, finally. “But when people are like, ‘Whatever you’re doing, it helped me’ – I don’t think any award or any money or whatever can be exchanged for that compliment. I don’t care about anything else, except giving space to people to be free. Because that’s what I needed so bad: freedom.”

CREDITS

HAIR Dom Forletta at Forward Artists MAKEUP Yadim at Art Partner using Valentino Beauty NAILS Juan Alvear at OPUS Beauty using Bio Seaweed Gel SET DESIGNER Nicholas Des Jardins at Streeters PERSONAL STYLIST Genesis Webb LOCAL PRODUCTION Family Projects EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Olivia Gouveia PRODUCERS Olivia Roper-Caldbeck and May Powell PHOTOGRAPHER’S ASSISTANTS Annabel Snoxall and Sabrina Victoria STYLIST’S ASSISTATNTS Hollie Williamson, Ada Matylda, Amilia Howells and Jester Bulnes MAKEUP ASSISTANTS Joseph Rios and Mila Kwan SET DESIGNER’S ASSISTANTS Josh Puklavetz MANICURIST’S ASSISTANTS Tohko Nishimoto PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS Kim Romero and Leonard Murray